The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in Northern Ireland has undergone significant transformation since Northern Ireland’s ‘peace deal’, the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. Much of this transformation has been brought about by a sizeable influx of new members. The impact of new members is a surprisingly under-researched area. Here, Raul Gomez and Jonathan Tonge draw upon a recent membership study to examine how new arrivals contributed to altered attitudes from the DUP.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in Northern Ireland has undergone significant transformation since Northern Ireland’s ‘peace deal’, the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. Much of this transformation has been brought about by a sizeable influx of new members. The impact of new members is a surprisingly under-researched area. Here, Raul Gomez and Jonathan Tonge draw upon a recent membership study to examine how new arrivals contributed to altered attitudes from the DUP.

The difference between the DUP of the late 1990s/early 2000s and today is remarkable. From being a party of protest, it has been one of power over the last decade. Having threatened to ‘smash Sinn Fein’, it now shares power with that party. Having overtaken its internal bloc rival, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) by 2003, the DUP proceeded to accept all it had repudiated in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement when signing the St Andrews Agreement in 2006, albeit also obliging Sinn Fein to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

Much of this transformation can be attributed to the desire of the DUP leader from 1971 until 2008, the Reverend Ian Paisley. His own brand of politicised Protestantism was belligerent. Paisley used his party as a vehicle for his fundamentalist Free Presbyterian Church, which he also founded. His political and religious vehicles were based upon perma-opposition until the DUP became the largest party in Northern Ireland in 2003. Paisleyite strictures expressed opposition not merely to the violent campaign of the ‘Roman Catholic IRA’ (for a united Ireland from Ulster’s ‘Chosen People’) but also to homosexuality (‘Save Ulster from Sodomy’); the EU (a Roman Catholic conspiracy); the ecumenical movement, and to an eclectic succession of political leaders, ranging from every UUP leader to Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, who had all engaged in acts of ‘betrayal’.

Unprecedented electoral success amid Unionist anxieties over the Good Friday Agreement offered Paisley the chance to become First Minister and end his career as a ‘statesman’ rather than as a bombastic, marginalised oppositional figure. Paisley’s new-found willingness to find politically acceptable all that had been previously ‘morally unjust’ was clearly a derivative of the party’s newly dominant status. Even in a top-down organisation, the DUP leader had to carry his party and it is in this respect that the new influx was crucial. Almost one-quarter of DUP members once belonged to the UUP. Most defected during the early 2000s, joining the DUP in opposition to particular aspects of the Agreement and its aftermath – such as the release of ‘terrorist’ prisoners and changes to policing and were seen as ostensibly hardline.

Crucially, however, many of the ex-UUP members – and others who have joined the DUP since the early 2000s – did not reject power-sharing with Irish nationalists per se. Rather, they wanted devolution; accepted the principles of shared cabinet positions; supported the need for weighted cross-community support and even (just) endorsed all-island economic bodies. Provided Sinn Fein moved their associates in the IRA to call off its armed campaign and decommission weapons, and offered support for the police, all of which happened by early 2007, newer members were ready to move to sharing power with Sinn Fein. Softer stances on all these positions are not merely attributable to the possibilities of youth. What matters attitudinally in the DUP is when a member joined – not how old they are.

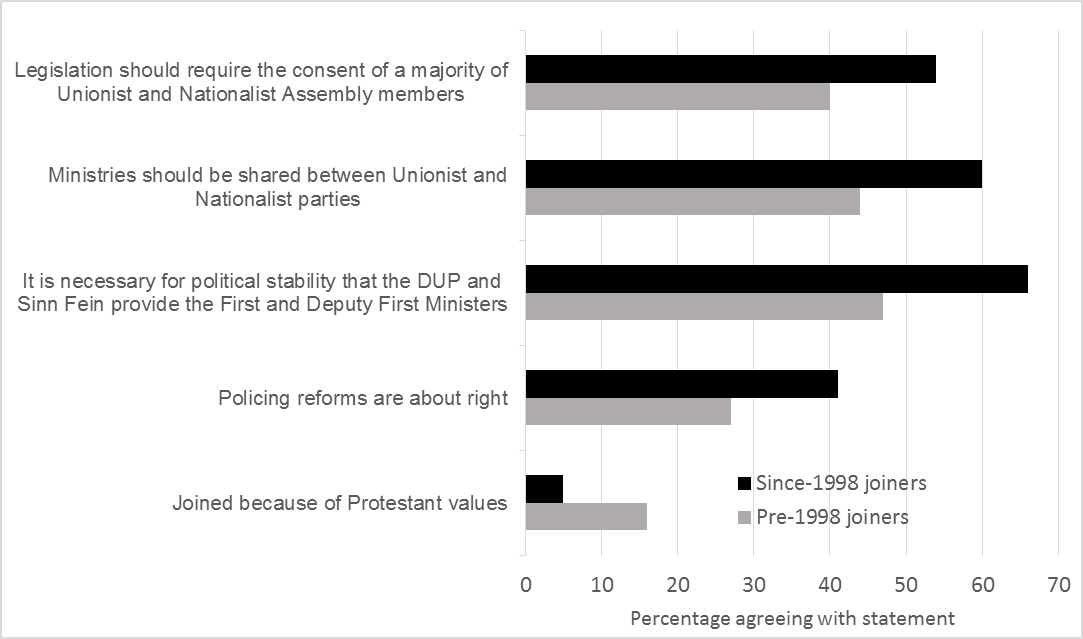

The DUP modernised its internal structures to give voice to the new arrivals. Special advisers rewrote policy documents to give a more positive tone, offering to ‘put right’ the existing deal rather than merely end it; new members were fast-tracked into the party’s policy unit; obstructive hardliners were marginalised and excluded from meetings with government advisors; and some of the new intake were promoted – one UUP defector, Arlene Foster, now leads the DUP. The graph shows some differences between the pre-1998 joiners and those since. It show a increased and now-comfortable(ish) acceptance of power-sharing with the old republican enemy from the later joiners.

Pre-1998 vs since-1998 members of the DUP

Furthermore, the arrivistes are also of a different religious outlook – non-Free Presbyterian and far less desirous of ‘faith and church’ dominating the DUP in the way it once did. Further results from our survey showed that using a zero (no religious influence) to ten (total influence) scale, joiners since the Good Friday Agreement register a mean score of five; in comparison, pre-1998 members offer a mean score of nine. Whilst a score of five hardly represents the omnipotence of secularism, it amounts to a major shift. The percentage of post-1998 joiners citing ‘Suited my Protestant values’ as their primary reason for joining the DUP is only six per cent compared to one-third of pre-1998 joiners. Newer joiners are much less likely to believe that ‘homosexuality is wrong’ whereas a large majority of pre-1998 joiners are of this view. Whether this shift will herald a softening of attitudes on same-sex marriage (or abortion) remains to be seen, as DUP Assembly members appear resolutely against change at present.

Change also appears possible on cultural expressions of Protestantism. Routes of some Orange Order parades have been a source of sectarian controversy and associated violence. Newer DUP members are much less assertive of unfettered marching rights and much more prepared than older members to accept the compromise that the Orange Order should only march near interfaces with the agreement of local nationalist residents. This softening of approach is already feeding into DUP thinking on how to replace the current regulatory body, the Parades Commission.

New members can change the outlook of a party, taking it in directions few people once expected. Given that most UK political parties have seen an influx of new members in recent years, it is time to take seriously the how the attitudes of new members might differ from longer-standing members – and what changes might be wrought as a consequence.

This discussion draws on the article ‘New Members as Party Modernisers: The case of the Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland’ published in Electoral Studies. It uses data from a DUP membership study sponsored by the Leverhulme Trust.

Raul Gomez is lecturer in Politics at the University of Liverpool.

Raul Gomez is lecturer in Politics at the University of Liverpool.

Jon Tonge is Professor of Politics at the University of Liverpool and co-author of The Democratic Unionist Party: From Protest to Power (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Jon Tonge is Professor of Politics at the University of Liverpool and co-author of The Democratic Unionist Party: From Protest to Power (Oxford University Press, 2014).