Reforming the welfare system has been a key aim of British government since 2010. Richard Machin writes that the concept makes no economic sense, it does not produce the outcomes the government is seeking, all while the UK is actually spending less on welfare than countries with comparable economies.

Reforming the welfare system has been a key aim of British government since 2010. Richard Machin writes that the concept makes no economic sense, it does not produce the outcomes the government is seeking, all while the UK is actually spending less on welfare than countries with comparable economies.

Back in 2010, the coalition government stated that welfare reform is essential to make the benefit system more affordable and to reduce poverty, worklessness, and fraud. The 2017 manifestos of the main parties offered a genuine choice of whether to pursue or abandon this policy. For working-age benefit claimants, Labour and the Liberal Democrats proposed a series of sweeping reforms including the abolition of the ‘bedroom tax’ and the sanctions regime. A lack of detail in the Conservative manifesto could be read as an intention to continue with the roll-out of the many changes that we have seen over the last seven years, although planned changes to benefits for pensioners have been abandoned under the confidence and supply agreement with the DUP.

In the aftermath of the election where does this leave us? For working-age claimants presumably we will see the minority government pursuing the welfare reform programme. Political opposition to austerity – both in Westminster and with voters – has gained some traction as a consequence of the election result, and there are strong arguments that welfare reform has failed to meet its intended aims and negatively impacted on claimants.

Welfare reform does not make economic sense

Research by Sheffield Hallam University found that the post-2010 welfare reform policies will take £27 billion a year out of the economy, or £690 a year for every adult of working-age. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate that the cash freeze to most benefits, and cuts to child tax credit and universal credit, to be pursued in this parliament, will affect 3 million working households. The Cambridge University economist Ha Joon-Chang argues that the mainstream political narrative that welfare spending is a drain and should be reduced is illogical. He asserts that ‘a lot of welfare spending is investment’ and believes that appropriate funding in areas such as unemployment benefits can improve productivity and workforce capability.

When thinking about what an appropriate welfare state looks like in this parliament we would also do well to consider the findings of Professor John Hills’s latest book, which emphasises that we all rely on ‘welfare’ at some point in our lives. A sensible debate about the affordability of welfare benefits should be framed with reference to accurate statistics about the recipients of welfare spending. The Institute for Fiscal Studies report that 46.43% of total social security spending goes on benefits for older people, with only 12.82% on benefits for people on low incomes (for example housing benefit) and just 1.11% on benefits for unemployed people. The government’s aim of producing a fairer and more affordable system is hamstrung by ignoring fiscal facts on one hand while perpetuating inaccuracies about the profile of benefit claimants on the other.

Professionals working in the advice sector have long advocated the principles of the ‘multiplier effect’. This argues that there are economic advantages to high levels of benefit take-up as claimants spend money on goods and services in the local community. Ambrose and Stone (2003) found that a multiplier effect of 1.7 exists, meaning each pound raised in benefit entitlements for claimants should be multiplied by 1.7 to give a much greater overall financial benefit to the economy.

My own experience of working in advice services demonstrated that where household incomes are protected through adequate levels of social security there are direct savings to the public purse: rent/council tax arrears are avoided, contact with overstretched public services is reduced and improved health outcomes reduce burdens on the NHS.

Welfare reform is regressive

There is clear evidence that welfare reform has a disproportionately negative impact on some groups in society and some areas of the UK. The Sheffield Hallam research found that those particularly hit by welfare reform are working-age tenants in the social rented sector, families with dependent children (particularly lone-parent families and families with large numbers of children) and areas with a high percentage of minority ethnic households. Geographically, the impact of welfare reform is stark with the greatest financial losses being imposed on the most deprived local authorities. As a general rule, older industrial areas and some London Boroughs are hardest hit, with southern local authorities the least affected.

The mainstream media often fails to report the true impact of welfare reform that this research highlights. A more accurate account of the human costs can be found in ‘For whose benefit? The everyday realities of welfare reform’ in which Ruth Patrick documents her research on the impact of sustained benefit reductions. Dominant themes include the stigma felt by benefit claimants, the negative impacts of a punitive sanctions regime, and living with persistent poverty.

Welfare reform does not produce the behaviour changes sought by the government

Although welfare reform is a values-laden policy underpinned by a strong, but flawed, ideology (only those who fail ‘to do the right thing’ are affected) there is little evidence that the retrenchment of the welfare state has been accompanied by the change in claimant behaviour that politicians desire. The ‘bedroom tax’ was supposed to ‘provide an economic incentive’ to move to smaller accommodation. The evaluation indicates that more than 7 in 10 claimants affected had never considered moving, with an estimate that no more than 8% of those affected having downsized within the social sector.

The Benefit Cap places a limit on the total amount of certain working age benefits available to claimants. One of the government’s main intentions was for this to improve work incentives. There is no common consensus on the extent to which this aim has been achieved: the Institute for Fiscal Studies have suggested that the majority of those affected will not respond by moving into work, however, government ministers rarely waste an opportunity to tell us that low levels of unemployment are partly due to the benefit changes introduced.

The research of David Webster into sanctions argues that ‘Sanctions are not an evidence-based system designed to promote the employment, wellbeing and development of the labour force’ and that this regressive system results in lower productivity, pointless job applications, and poverty-related problems.

In the last days of the previous administration we saw the introduction of the 2-child limit for child tax credit and universal credit. Child Poverty Action Group emphasise the contradiction in a policy which supposedly provides parity between those in work and those out of work, when 70% of those claiming tax credits are already working.

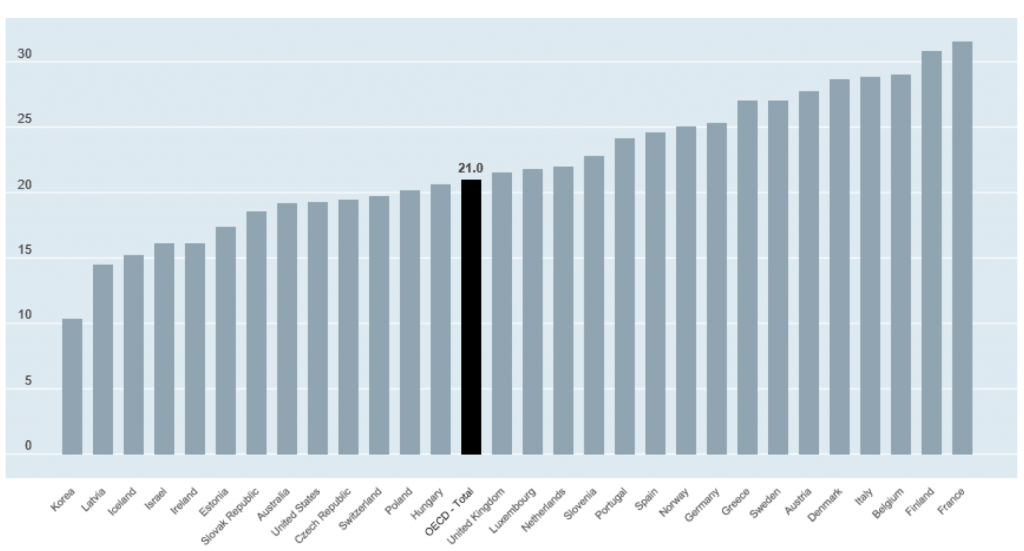

Comparable countries spend more on their welfare systems than the UK

Given the huge variations in social security systems across countries, a true comparative exercise is somewhat problematic. However, we can again rely on the analysis of Ha-Joon Chang who debunks the myth that the UK has a large welfare state. Taking public social spending as a percentage of GDP, the UK is only slightly higher (21.5% of GDP) than the OECD average (21%):

OECD (2017), Social spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7497563b-en

OECD (2017), Social spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7497563b-en

Moving forward a key challenge for all political parties is to start a serious conversation about benefits for older people and how to create a sustainable system with an ageing population. At the other end of the age spectrum, much has been said about the increased engagement of younger people in the political process; ironically many commentators argue that it is this age group that will be hardest hit by a continuing programme of welfare reform.

______

Richard Machin is Lecturer in Social Welfare Law, Policy and Advice Practice at Staffordshire University.

Richard Machin is Lecturer in Social Welfare Law, Policy and Advice Practice at Staffordshire University.

A really interesting read. Thank you.

Ok…there is a lot more we need to be concerned with the roll out of universal credit and the way it is impacting those ill and disabled of working age. It is staggering what the new regulations allow. People with uncontrollable progressive diseases still subject to work-focused interviews with work-coaches from job centre plus…in fact anyone who has been declared unfit for work and not fit for any work-related activities through the wor-capability assessment are STILL put in a work-focused interviews by local JCP and their work-coaches…imagine having Parkinson’s disease, be diagnosed with cancer and have this constant intrusion and pressure from JCP…all this is daily occurrence in my job. This is a further shift from previous practice another twist of the screw…the power given to front line work-coaches with NO medical training or competence… I am happy to discuss this with anyone interested …I work on the front line of welfare rights and I fear I am becoming powerless to do much to support people who come to me….

Has there really been a call to abolish the “the sanctions regime”? This https://mrfrankzola.wordpress.com/2017/05/19/obfuscation-and-words-words-words-words-like-regime-unfair-exploitative-and-punitive-no2sanctions/ suggests no such undertaking has been made by any UK political party (Labour, Liberal, SNP and Tory)

The so called welfare reform, welfare is actually the american version, was decided upon on a flawed idea that by making it hard together any benefits people would be returning to work in droves. Not surprising those who couldn’t work with benefits were no more capable of working without them and did not return to work. The so called numbers of people it has got back into work include those who have killed themselves, died of neglect, or have been sanctioned, and are not getting any help they desperately need. We need a complete overhaul of the benefits system so that the desperate people who need help can actually get it, and those rich people who receive unneeded bene=fits don’t get them anymore.

Of the many articles that I have read on welfare reform, this is far and away the best. Evidence-based and in my experience of working with hundreds of social housing providers and their residents, entirely accurate regarding the outcomes for those affected.