Despite indications that economic growth is picking up, the coalition government shows no sign of moving away from its austerity programme. Lucy Lee considers why the majority of Britons have accepted austerity and whether any lack of widespread protest against it is a sign of increasing political disengagement.

Despite indications that economic growth is picking up, the coalition government shows no sign of moving away from its austerity programme. Lucy Lee considers why the majority of Britons have accepted austerity and whether any lack of widespread protest against it is a sign of increasing political disengagement.

George Osborne’s Autumn statement was heralded as good news: GDP growth has begun to rise more quickly and unemployment is starting to fall. However, the IFS has noted ‘there’s even more austerity than we’d expected’, pointing to lack of funding for free school meals after 2015, and an increase in the pace of public service spending cuts over the coming years. And, as Joel Suss pointed out on this blogsite earlier this month, a message of GDP growth ignores the danger that this rise rests on unsustainable household spending. Amidst all this has been the unfortunate debacle over MPs’ pay rises. In this context, we consider whether the majority of Britons accept the Coalition’s austerity programme, and whether any lack of widespread protest against austerity is a sign of increasing political disengagement.

Using data collected by NatCen Social Research’s British Social Attitudes survey –which has asked the public its views on a number of topics, including public spending, since 1983 – we can explore both these questions.

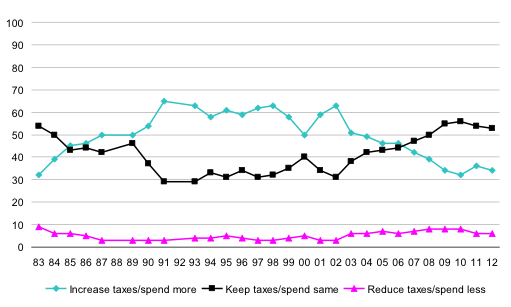

We start by looking at the public’s views about government taxation and spending. Of course, attitudes towards government spending are influenced by a number of factors, not least comparisons of what the government is perceived to be spending with the respondent’s ‘ideal’ level of spending, people’s understandings of the value of individual welfare benefits (which are often inaccurate) – and attitudes towards different types of benefit recipient. Figure 1 shows that the proportion thinking the government should increase taxes and spend more on health, education and social benefits declined between 2002–2010, with a slight upturn in 2011; our latest reading in 2012 stands at 34% favouring increased taxation and spending.

Figure 1: Attitudes to tax and spend, 1983–2012

We should bear in mind that additional spending seems less necessary when government spending is increasing rapidly (as it was under the last Labour government), and that when the government is trying to reduce its overall budget deficit by cutting spending (as Labour did latterly, and the Coalition is now doing) this will persuade some people that extra spending is just not possible. So changes in support for increased public spending are at least partly responses to government activity. It is also apparent that policy stances taken by particular political parties will influence the views of their supporters. For example under the 1997–2010 Labour government the party, and in turn many Labour supporters, became less pro-welfare. There has been a marked decline in the proportion of Labour supporters supporting redistribution: 53% do so in 2012, compared with 69% in 1987.

But it is not only Labour supporters who have become less pro-welfare over the past decade. When we ask people whether the government should be the main provider of support to the unemployed we see a dramatic decline: from 81% of people saying government should be the main source of support in 2003 to 69% in 2011. While all groups have seen a decline, this has been more marked among some – Conservatives, professionals and those not in receipt of benefits have shown the greatest decline and are less likely to think government should fulfil this role than people from other backgrounds. Where we saw a rough consensus in 2003, there are greater disparities between groups on this matter now. Similarly, all groups are more likely to agree that unemployment benefits are ‘too high and discourage work’ than they were a decade ago, although large differences by demographics are also evident here.

So there may be a general acceptance among much of the public of the need for Osborne’s continued austerity, resulting from a mixture of (i) seeing that money is scarce and being convinced that extra spending is impossible and (ii) a general move towards a less pro-welfare stance that occurred among much of the public over the last decade. However, it’s worth saying that our 2012 survey did show a slight upturn in support for welfare recipients, and the increasingly divergent views held by different sections of society do not bode well for any government aiming to carry public opinion during a period of economic hardship.

What of our second question – whether any lack of protest against austerity is a sign of increasing political disengagement? British Social Attitudes findings certainly do paint a picture of an increasingly disengaged electorate – with fewer people identifying with a political party, fewer feeling the political system works for them, and fewer deeming it a ‘civic duty’ to vote than did so 30 years ago. At the same time, the proportion saying they ‘almost never’ trust government has risen from 11% in 1986, to 32% now. These changes reflect a number of factors. We can see a period effect (when certain factors – such as the MPs’ expenses scandal of 2009 – have had an impact on all groups in society), a generational effect (with each successive cohort of voters entering the electorate being less likely than the one before to identify with a political party), and a lifecycle effect which seems to be differentially affecting younger cohorts. Again, when we look at attitudes by demographics, we see concerning signs of markedly divergent views among the public: those with lower educational qualifications are less likely to be interested in politics or to think it’s everyone’s duty to vote, and less likely to feel able to understand politics or to feel they have a say in what government does.

That said, there are some signs of increasing engagement – interest in politics is higher than in 1986; after a long period of steady decline, people’s belief in their duty to vote has risen slightly over the last few years; and the long-term trend in people’s belief that they can make a difference is upwards, even if most people still feel they cannot do so.

What is really notable from our work is that those most adversely affected by government spending cuts are often the least likely to be politically engaged or to feel they have the ability to voice their concerns. Those who feel more politically engaged and able to voice their concerns are largely those who have become less pro-welfare over the past decade or so. As the effects of the latest recession continue, and the Coalition’s welfare reforms come into play, we watch with interest how public attitudes towards government reforms and cuts, necessitated by the experience of austerity, will change over the coming years.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Lucy Lee is a Senior Researcher at NatCen Social Research, and project manages and co-edits the British Social Attitudes survey series.

Lucy Lee is a Senior Researcher at NatCen Social Research, and project manages and co-edits the British Social Attitudes survey series.

Well the rich might be seeing an improvement, but the people who are paying the price for it are very unlikely to see any improvement for a long time. Not rocket science is it, when nurses get a 1% raise to their already meagre salary, and MP’s get 11% raise to their already good salary.