Last week the Prison Reform Trust (PRT) and Bromley Trust released an innovative new ‘app’ for anyone interested in keeping an eye on the ever-persistent operational pressures on the UK prison system. ‘Prison: the facts’ is downloadable free through i-Tunes, and transforms the excellent Bromley Briefings for a digital-era audience. Getting more ‘facts’ about prison life out into the open is clearly a vital public service, says Simon Bastow, but it assumes that there is consensus about what the facts actually are.

Last week the Prison Reform Trust (PRT) and Bromley Trust released an innovative new ‘app’ for anyone interested in keeping an eye on the ever-persistent operational pressures on the UK prison system. ‘Prison: the facts’ is downloadable free through i-Tunes, and transforms the excellent Bromley Briefings for a digital-era audience. Getting more ‘facts’ about prison life out into the open is clearly a vital public service, says Simon Bastow, but it assumes that there is consensus about what the facts actually are.

In any policy system, the relationship between fact and value is complex. We rely on putative fact as a foundation for shaping and supporting value-based judgements about policies. At the same time, facts are of course susceptible to different interpretations about assumptions and the worldviews that underpin them. Both facts and values can carry intrinsic or instrumental value too, and sorting out the dynamics in their interplay requires careful analysis.

Over the years, the Bromley Briefings have done much to synthesize and communicate the facts about the UK prison system. Policy-makers and prison-watchers alike have benefitted from the wealth of quotable factoids in these publications. Indeed, they have kept the spotlight on the problem of prison crowding and capacity stress, and the new app looks set to continue this strong tradition of getting the facts across, now to a digital audience.

The medium of communication may change, but the fundamental chronic problem of crowding does not. The press release for the launch reads:

‘still 6,092 more people in the prison system than it is designed and built to hold’

‘there were 72 out of 124 establishments over the Certified Normal Accommodation, the good and decent standard of accommodation that the Service aspires to provider to all prisoners’.

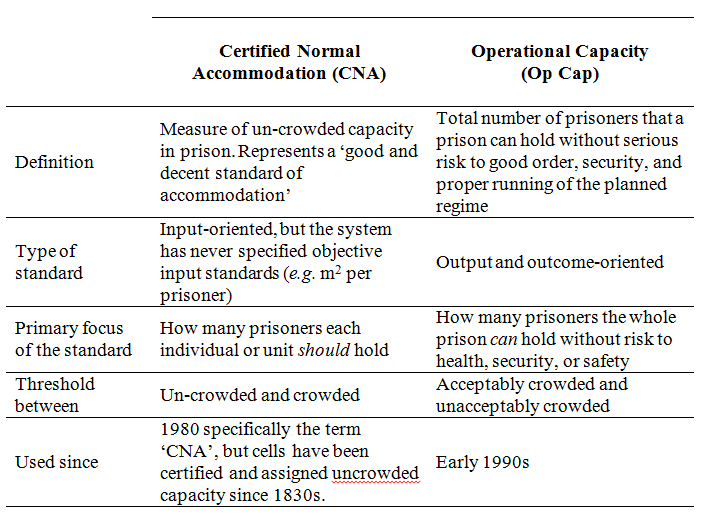

This is by now a familiar refrain. Yet if we look in more detail at the nature of the measures or standards that have been used to assess crowding and capacity, we find quite complex value-based dynamics at work that compel us to interpret these ‘facts’ in a more nuanced and balanced light. Central to this has been the relationship between the two main standards that have been used to measure prison capacity during the last few decades:

– Certified Normal Accommodation (CNA); and

– Operational Capacity (Op Cap).

When the PRT talks about prison overcrowding, it is talking about the system being overcrowded against its CNA. This general concept of certifying prison accommodation has been around since the 1830s; however it was not until the late 1970s that one begins to find specific reference to CNA in official Prison Service documentation. As the quote above reads, it represents ‘a good and decent standard of accommodation’, a level of capacity based on what each prison is designed and built to hold.

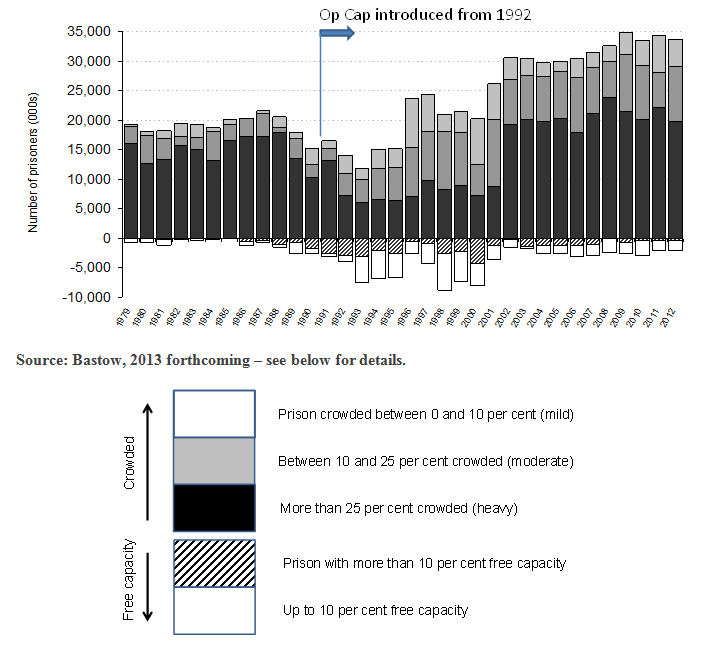

A key point here is that CNA has traditionally been a ‘cell-based’ measure. In other words, each cell is assessed on the number of prisoners it was originally designed to hold, and the capacity of the prison is calculated by summing the total of all cells. The problem here is that a large proportion of local prisons in the estate (where most of the crowding has been) were originally designed and built in the Victorian era, and most cells in these Victorian local prisons were built specifically to accommodate a single prisoner in solitary conditions. As the modern prison system has evolved and as population pressures have increased, most of these single cells have been ‘doubled’, and this has accounted, in large part, for the continually crowded state of the system. Figure 1 below shows this chronic picture of overcrowding, measured specifically against CNA.

Figure 1: Number of prisoners held in ‘local’ prisons that are crowded above Certified Normal Accommodation (CNA)

From the early 1990s, however, officials running the prison system began to use a new measure in parallel to CNA for managing crowding, Operational Capacity or ‘Op Cap’. Whereas the primary focus for CNA was on how many prisoners each individual cell could hold, the focus for Op Cap was on the ‘whole prison’ level, i.e. how many the prison can hold ‘without risk to health, security, or safety’. Rather than distinguishing, as CNA does, between un-crowded and crowded, Op Cap drew the line between what was ‘acceptably crowded’ according to these three considerations, and what was unacceptably or ‘over’-crowded. Of course the beauty of this is that if Op Cap is constantly stretching to accommodate increase in prisoners, the system is really in a state of ‘over’-crowded. It is perpetually in a state of being ‘acceptably’ crowded.

This new measure allowed the system to flex or stretch quite considerably through the period of rapid increase in the prison population throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Op Cap was the ‘managerial measure’, the judgement made between governors and their line managers about the increments of crowding that could be absorbed by their individual prisons with incurring ‘unacceptable’ risks on health, security, and safety. In a situation where senior managers had to find ways of coping with this increase in the prison population, Op Cap served as a legitimate measure or standard with which to regulate the increasing stretch in the system.

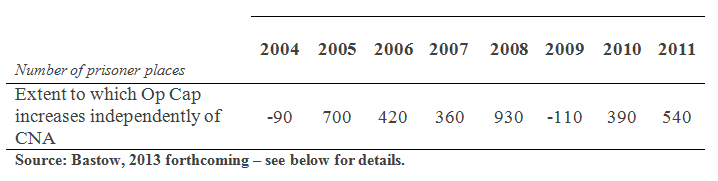

In reality, while the CNA of a local prison would remain (officially) the same, the Op Cap would stretch away from the CNA as single cells were ‘doubled’. Table 1 below shows the extent of the stretch year-on-year between 2004 and 2011.

Table 1: Estimated ‘net stretch’ of Op Cap away from CNA, 2004 to 2011

So the two measures have evolved in parallel, and continue to perform different functions in the moral and managerial operation of the system. Each measure on its own, it can be argued, has serious flaws. Yet when looked at as a form of ‘control through counterbalance’, their combined effect is conceivably much stronger and more compelling – a kind of force-field that constrains the system from moving towards the excesses of one or the other.

In many ways, CNA looks like a relic, an artefact, a ‘desideratum’ from a bygone Victorian era. For many officials in the system, and for those concerned prison watchers looking in, CNA has provided a kind of ideal-type standard, as some have termed it, a ‘gold standard’ for capacity. But as we can see from Figure 1, the system has not been anywhere near that standard, gold or otherwise, for at least three decades. How long must a standard remain obsolete before it is seen as such?

Normatively too, single cells were built for a Victorian system based on the belief that keeping prisoners in solitary conditions was constituent in their rehabilitation. Given that this belief is largely defunct in the modern era, how much should we continue to rely on it? On these grounds, it seems that CNA is a reflection of obsolescence, rather than a reflection of a relevant and realizable aspiration for a modern prison system.

For Op Cap meanwhile, the problem of inevitable stretch means that in reality it is unable to resist the increments in population pressure. Although many officials argue that it has moral integrity, it can also be shown that it stretches as and when necessary. An important consideration here is the social relations involved in the decisions to allow stretch. These are made by governors in discussion with their line managers, and undoubtedly governors are under pressure to agree to the request to stretch.

On the other hand, Op Cap provides a managerial impetus in the system to challenge existing levels of capacity. There is after all no magic formula that prescribes a certain level of input for an acceptable level of output or outcome. If a prison can maintain acceptable (or even excellent) levels of performance while at the same time pushing the numbers that prisons can accommodate, this counts after all as productivity improvement. As one of the more ‘can-do’ officials in the private sector put it:

It’s a myth. I don’t want to think about it. I don’t want to create the pressure in mind that it is a difficult job. They will say, ‘but your prison is only built for such and such [ … ] and you’ve got more than twice that number’. But we don’t focus on overcrowding. Or whatever. I don’t want to get bogged down in it. The day I use it as an excuse, I’ll use it until the day I die.

So excessive movement one way or the other is the risk. The very concept of CNA has an obsolete feel to it in a system that has managed to find quite significant performance improvements throughout the managerialist era. The danger here is that we cling on to obsolete capacity standards that constrain the push towards improved value for money of the system overall. As I show in my forthcoming book, the prison system has managed to improve performance and standards considerably in recent decades, despite retaining a continual state of crowding above CNA.

But as we have discussed above, CNA has been an important part of control through counterbalance, one side of the countervailing force-field that currently keeping the prison system in some kind of manageable capacity equilibrium. The danger is that the hyper-managerial and outcome-based logic of Op Cap is allowed to prevail too far. In today’s system, the risks of paring down resources and investment to its bones are equally visible, and will become more so as the prison system as austerity bites. Thinking that private sector ethos or managerial evangelism can neutralize these risks is at best ideological, and at worst, just plain naive.

So it is no surprise that the PRT over the years hardly ever mentions Op Cap as a legitimate measure. It has been ‘CNA all the way’. This has been the moral bedrock of the capacity and crowding debate over the years. But for the PRT and other pressure groups, it is also the foundation upon which the instrumental argument can be made that the prison system is failing and will ever thus fail until the prison population is reduced against a static level of capacity. The difficulty with this line of argument is that neither one nor the other is ever static. They are both dynamic, and the measures and standards that frame them are dynamic too. Describing the prison system as over-crowded (against CNA) is one side of the story. In order to understand the story in full, we need to look at the inter-relationships of both.

Table 2: Contrasting Certified Normal Accommodation (CNA) and Operational Capacity (Op Cap)

Simon Bastow has a book forthcoming on the England and Wales prison system – ‘Governance, performance, and capacity stress. The chronic case of prison crowding’. Published later in August 2013 by Palgrave Macmillan.

Simon Bastow has a book forthcoming on the England and Wales prison system – ‘Governance, performance, and capacity stress. The chronic case of prison crowding’. Published later in August 2013 by Palgrave Macmillan.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Simon Bastow has been a Senior Research Fellow at the LSE Public Policy Group since 2005. He was previously at the School of Public Policy, UCL (now the Department of Political Science). He completed his PhD in political science in April 2012, looking at chronic capacity stress and crowding in the England and Wales prison system.

1 Comments