The National Audit Office (NAO) focused attention last week on the challenges of managing the prison estate in England and Wales. The report raises questions about how we reconcile running the estate at close to 100 per capacity while, at the same time, realizing the government’s Transforming Rehabilitation agenda. Simon Bastow explains inherent limitations involved in trying to do both.

The National Audit Office (NAO) focused attention last week on the challenges of managing the prison estate in England and Wales. The report raises questions about how we reconcile running the estate at close to 100 per capacity while, at the same time, realizing the government’s Transforming Rehabilitation agenda. Simon Bastow explains inherent limitations involved in trying to do both.

Senior prison officials in recent decades have had to find ways of continually resolving a recurring managerial dilemma. As the prison population has increased from the 1990s onwards, so has pressure to find new capacity in the estate, either through adding accommodation or crowding existing prisons. Meanwhile the pressure to reduce costs and find efficiencies has meant that these officials have sought to squeeze existing capacity in the system, so much so that for at least the last decade most large prisons have operated almost continually at somewhere between 95 per cent and 100 per cent of their maximum capacity.

The dilemma is that by pushing the system towards these close-to-tolerance levels, both out of necessity and in the quest for ever-higher cost-efficiency, ageing or inadequate accommodation and facilities are sustained, when ideally they should be decommissioned and replaced with more modern ones.

(Credit: Nabokov)

Last week’s NAO report provides rich illustration of this dialectic. Its examination of the NOMS estate strategy (2010 onwards) shows that 15 prisons have been closed or have been scheduled for closure since 2010 (around 4,000 prisoner places). This, they estimate, is equivalent to £71m costs saved by the end of 2014.

Anyone who has visited Shrewsbury, Gloucester, Lancaster Castle, or The Verne prisons, four of the more anachronistic establishments that have been decommissioned, is struck by the sheer physical obsolescence (and inadequacies) of these places. The point is that they should have been shut years ago. Had we not desperately required the capacity, they would have been.

Yet without a significant drop in the prison population, decommissioning 4,000 places must be offset by adjustments elsewhere in the estate. And the report points to increments in crowding levels, as well as marginal increase in the average size of prisons by around 10 per cent. These are the kind of adjustments that can be absorbed throughout the estate as a whole.

An important further measure is a more efficient use of existing capacity by moving prisoners around the estate. Since the mid-1990s, the prison system has relied on ‘overcrowding drafts‘ to resolve regional imbalance between demand and supply of prison capacity. This has involved systematic and planned movement of prisoners (usually short-sentence) between establishments in order to make room for new intakes.

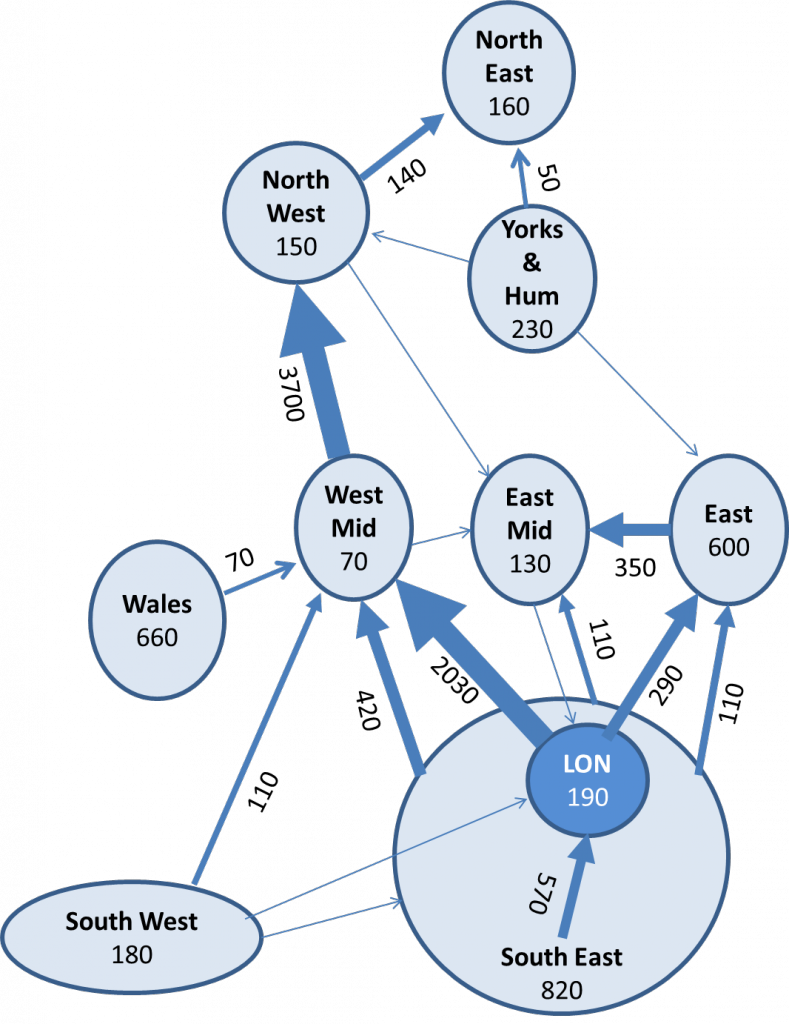

While researching my book in 2010, NOMS ‘population management’ officials provided me with data that showed the flows of prisoners moved on ‘overcrowding drafts’ in 2009. Figure 1 shows the overall net flow of prisoners moved during that year. The direction of the arrows signifies net flow, and numbers of prisoners involved.

Figure 1: Net flows of prisoners transferred on overcrowding drafts, 2008 to 2009

Source: My analysis of NOMS data, 2008 to 2009

By 2009, this continual movement of prisoners had become a ‘life-support’ machine allowing the system as a whole to absorb increasing population pressures, and (proudly) claim that it was operating at near to 100 per cent capacity. London had historically been the motor for this continual movement due to its shortage of prison capacity. As Figure 1 shows, the main movement of prisoners was up the M40 to Birmingham, with a knock-on effect of prisoners moving up the M6 to Liverpool and Manchester.

The picture in 2013 looks broadly similar. Figure 2 below reproduces data from this latest NAO study on ‘prisoners produced’ minus ‘available capacity’ by region. Clearly the London capacity deficit is still a critical influence on the rest of the system. The surrounding regions, particularly the eastern and south eastern regions, continue to absorb pressure from London, and we still see signs of population pressure in the North West.

Figure 2: Prisoners produced minus available capacity in different regions in England and Wales, 2013

Source: NAO 2013 Managing the prison estate

These ongoing capacity pressures raise important questions for government’s Transforming Rehabilitation agenda. The plan designates 70 prisons in the estate as ‘resettlement prisons’, in which short-sentence offenders will serve their whole sentence and have access to targeted supervision and support. The ‘vast majority’ of offenders will be released from prisons in, or close to, the area in which they will live.

Yet one might ask how it is possible to keep prisoners in one place enough given that the whole stability of the national system relies on this constant and systematic movement. The paradox is tightened when we take into account the ever-decreasing resources in the system and the squeezing of available capacity. For rehabilitation to work, it will be important to minimize this systematic movement. But as capacity stress increases, this movement becomes increasingly necessary in order to keep the system as a whole in balance.

Admittedly, since 2010 NOMS has increasingly tried to avoid moving short-sentence prisoners and greater priority has been placed on keeping them where possible in closer proximity to rehabilitative support services in their local areas. Whether this prioritization will be sufficient to switch off the ‘life-support’ machine remains to be seen.

A further question relates to how it will be possible to measure attribution of individual prisons in Payment by Results (PBR) schemes. If the system must sustain this continual movement, one wonders how it will be possible to keep track of attribution of the rehabilitative effects of specific prisons along the way. It is all very well attributing intervention to one or two individual prisons that are involved in running PBR pilots. But as pilots these are relatively sheltered from the wider continual movement of prisoners. Rolling out PBR nationally becomes completely different prospect. The Ministry has been silent on these important issues so far.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Simon Bastow is a Senior Research Fellow at the LSE Public Policy Group. He recently published a book with Palgrave Macmillan ‘Governance, performance and capacity stress: The chronic case of prison crowding’.

Simon Bastow is a Senior Research Fellow at the LSE Public Policy Group. He recently published a book with Palgrave Macmillan ‘Governance, performance and capacity stress: The chronic case of prison crowding’.