Great strides have been made in black representation in U.S. politics since the 1960s, but there is still a way to go before equality in this area is reached. In new research, Paru Shah takes a look at the reasons behind black underrepresentation in elected offices. While many studies have tended to look at blacks’ chances of electoral success, she also focuses on factors which influence whether or not black candidates run in the first place. She argues that whether or not blacks run in elections can depend on prior black candidacy for the office, whether or not the seat is open, and whether or not the office is municipal, and finds that when blacks do run, they have a greater than 50 percent chance of winning.

Great strides have been made in black representation in U.S. politics since the 1960s, but there is still a way to go before equality in this area is reached. In new research, Paru Shah takes a look at the reasons behind black underrepresentation in elected offices. While many studies have tended to look at blacks’ chances of electoral success, she also focuses on factors which influence whether or not black candidates run in the first place. She argues that whether or not blacks run in elections can depend on prior black candidacy for the office, whether or not the seat is open, and whether or not the office is municipal, and finds that when blacks do run, they have a greater than 50 percent chance of winning.

By some accounts, the glass is half full. We have a black president, and the 113th US Congress includes two Asian American and two Latino Senators, as well as 44 Black and 30 Latino House members. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures most recent data, 13 percent of state legislators were non-white numbered over 1,000 in January 2009, comprising over of the total. And although the first election of a black mayor in a major city did not occur until 1967, today there at least 500 black mayors and 300 Latino mayors across America. In short, there is ample evidence that minority candidates are winning more elections in more places than ever before.

However, by other accounts, the glass is still empty. The last 50 years have witnessed tremendous growth in racial and ethnic minority populations in the US, and thus these gains in representation are interpreted by many as insufficient, reflecting the continued underrepresentation and perhaps disenfranchisement of racial and ethnic minorities from the political process. And as the racial and ethnic minority population edges closer to 50 percent of the US population, the gap in representational disparity grows.

What explains this gap in representation? Since the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, social scientists has investigated the question of why racial and ethnic minorities fail to achieve representational parity from a demand perspective – how do racial attitudes and behaviors among black and white voters restrict minority officeholding? In this project, I refocus the question of why we continue to see fewer black candidates in office than we might expect by focusing on the supply perspective – how often is lack of representational parity due to the defeat of the minority candidate versus the absence of minority candidates in the first place? I find that once candidate supply is accounted for, black candidates have a greater than 50 percent chance of win their election.

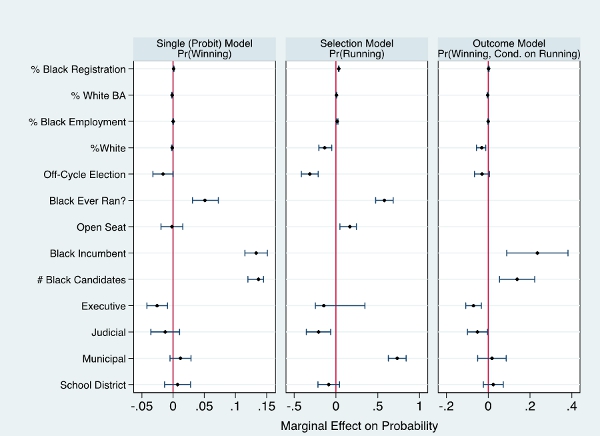

I focus on three broad categories of determinants often examined in minority representation research, and examine how these influence (1) the minority candidate supply in an election, and (2) the likelihood of a minority candidate winning, conditional on her running. The first category are the demographic characteristics of a jurisdiction or city, and include the black voter registration rates, percent white liberal population, and the resources of the black community, such as education and income. I expect the likelihood of a black candidate running and a black candidate winning to be positively associated with the percentage of black registered voters in a jurisdiction and to the resources available to them. The previous research on the effects of white liberal voters on representation is more mixed, and but I would expect their effect to be restricted to the second stage of winning an election.

The second group is political determinants. Given the legacy of racial discrimination and intimidation across the US, black candidates considering running for office may be wary of entering races in which they would be the first to break through the representational barrier. I expected the supply of black candidates to be greater for seats where blacks have previously run for that office, and where blacks have previously held that office. In addition, simple probability dictates a positive relationship between the number of black candidates running in a particular election, and the likelihood of a black candidate winning. And last, I expected the “incumbency advantage” to have important consequences for the supply of candidates, as strategic candidates should see an incumbent as a formidable blockade to their entry into an election.

The final set of variables that will impact the likelihoods of running and winning an elected seat are the institutional features of the election itself. In particular, I focus on two – timing of elections and type/level of office. The scheduling of elections influences voter turnout, with “off-cycle” elections (i.e. elections not timed with statewide primaries or general elections) reporting much lower voter turnout than on-cycle elections. I expect off-cycle elections to depress voter turnout, and therefore be a deterrent to strategic minority candidates. In addition, less “prestigious offices” (school board, city council) require less experience and less resources to run, and historically, minorities have excelled in winning these offices: over 90 percent of blacks and Latinos serving in elected office are in a municipal or school board seat.

To test these hypotheses, I utilize data from the Local Elections in America Project, gathered for the state of Louisiana between 2000 and 2010. Louisiana is the only state that both collects the racial identifiers of all candidates for office and makes this information public on its Secretary of State website. Thus this is a unique opportunity to examine the supply of minority candidates across a variety of offices over time. I then compare two models: the first (single model) replicates much of the current literature on minority representation on only asks: did a black candidate win? The second explicitly takes into account the selection bias introduced by the candidate supply, and asks two questions: did a black candidate run (selection model), and conditional on that, did a black candidate win (outcome model)?

Figure 1 – Marginal effects of variables of black candidacy

The marginal effects of each variable are considered in Figure 1, and lead me to two main conclusions. First, the results confirm that it takes a black candidate to run in order for the office to have a non-zero chance of welcoming a minority elected official, and this stage poses the highest hurdle. Once candidate supply is accounted for, black candidates have a greater than 50 percent chance of winning their election. Importantly, had we only examined the outcomes, the success rate for blacks would be closer to 28 percent, below the state black population average of 33 percent, continuing to contribute to the narrative of underrepresentation. But moreover, that blacks choose not to run in 60 percent of local elections is also telling. As new research on candidate emergence suggests, black candidates act strategically, avoiding races where there chances of winning are low due to racial competition. In other words, minority representation continues to be both a supply and demand issue.

Second, although this supply-side theory of minority representation is still nascent, this analysis examines the most commonly associated variables to descriptive representation (where elected representatives represent the characteristics of their constituencies as well as their preferences), and confirms the proposition that that the mechanism underlying running for office may be significantly different that the mechanism underlying winning office. Indeed, few variables matter for both stages. For example, the determinants of a black candidate on the ballot are heavily concentrated among the political and electoral determinants – prior black candidacy, an open seat, and a municipal office. At the second stage, the largest drivers of success are a black incumbent and the number of black candidates running. Importantly, many of the “usual suspects” determinants of minority representation – voting strength, resources, open seat and off-cycle elections – play a role solely in the first stage. Thus, we have been ascribing the influence of independent variables to election outcomes when those independent variables are in fact driving candidate emergence. A number of additional variables, including candidate quality and perceptions of candidate quality, as well as indicators of ambition, are required to unravel this relationship further.

This article is based on the paper It Takes a Black Candidate: A Supply-Side Theory of Minority Representation in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, credit Zennie Abraham (Creative Commons BY ND)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1tYFrQN

_________________________________

Paru Shah – University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Paru Shah – University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Paru Shah is an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Her research centers on American politics, with an emphasis on race, ethnicity and politics, urban politics, and public policy analysis.