For decades, the US trended towards greater levels of social inclusion, a pattern which has seemingly stopped and potentially begun to reverse since around 2015. Montgomery van Wart, Miranda McIntyre, and Jeremy L. Hall look at why social exclusion has been on the rise in the US, writing that declining social capital has led to greater feelings of grievance, social disintegration, victimization, defensiveness, hostility, and extreme partisanship, which in turn has radicalized many Americans. They call on leaders and public managers to stand up against social exclusion in everyday life by disseminating research, undertaking anti-extremism training and programs to support democratic and inclusive norms.

For decades, the US trended towards greater levels of social inclusion, a pattern which has seemingly stopped and potentially begun to reverse since around 2015. Montgomery van Wart, Miranda McIntyre, and Jeremy L. Hall look at why social exclusion has been on the rise in the US, writing that declining social capital has led to greater feelings of grievance, social disintegration, victimization, defensiveness, hostility, and extreme partisanship, which in turn has radicalized many Americans. They call on leaders and public managers to stand up against social exclusion in everyday life by disseminating research, undertaking anti-extremism training and programs to support democratic and inclusive norms.

As the embrace of extremism and radicalization in American politics and social life continue to undermine the fabric of society, the interlocking concepts of social inclusion, social exclusion, radicalization, and societal collapse demand attention. Moreover, the central role of political and administrative leadership in combating extremism and radicalization in a democratic society during challenging times is coming acutely into focus.

Social capital in unusual times

Journalists and politicians now speak regularly and openly about a cold civil war being fought between the polarized political left and the extreme political right in the United States. Consequently, elected leaders and public managers need to be prepared at all levels to address this rhetoric, or at the very least, to better manage through such chaotic and tumultuous periods.

Before looking at the forces rending society, what factors and features hold society together in the most effective way? Robert Putnam’s social capital theory suggests nine major elements: (1) broadly shared norms and values, (2) a common identity, (3) perceptions of fairness across society, (4) a general sense of trust, (5) social reciprocity even with those of opposing ideologies, (6) bridging organizations and networks, (7) meaningful opportunities for participation in a variety of social contexts, (8) shared channels of communication and facts, and (9) an overall sense of cultural inclusion or integration. During normal times, it has been appropriate to focus on this virtuous cycle in public administration as a largely nonpartisan discipline.

These are not, however, normal times in the US, nor around the world. In the case of the US, innumerable commentators have chronicled the rise of hyper-partisanship and the loss of social trust (in almost everything), along with the rise of hate crimes, uncivil demonstrations, violent political rhetoric, mounting geographical divisions, siloed communication, radicalism, and cults.

Our work aims to provide an overview of the important topic social exclusion and its “vicious” cycle, the process of radicalization, the potential for societal collapse (potentially going from violent demonstrations to civil wars) and some recommendations to combat the spread of social exclusion and radicalization.

Social exclusion

Despite deep patterns of social exclusion in the US historically, structural, and blatant social exclusion had been eroding steadily from Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 US Supreme Court decision which overturned school segregation, up through approximately 2015 on many fronts. The movement toward extremism on the conservative end of the political spectrum, however, had been building for 20 years before the election of Donald Trump. With his election as president, the strong shift in the Supreme Court to the right, and the political radicalization of a large portion of the population, the trend toward social inclusion appears to have stalled with a distinct possibility of reversing in some or many areas.

Social exclusion is what occurs when there is a widespread lack of the nine factors identified by Putnam as constituting social capital. A sense of social exclusion, no matter the facts or ideological position, encourages feelings of grievance, social disintegration or oppression, victimization, defensiveness, hostility, extreme partisanship, and self-defense. In the extreme, a sense of social exclusion (even by those who may be very powerful or “in power”) leads to rage, retribution, suppression of the rights of the “minority,” and acts of violence, such as riots, up to and including civil war.

Photo by Colin Lloyd on Unsplash

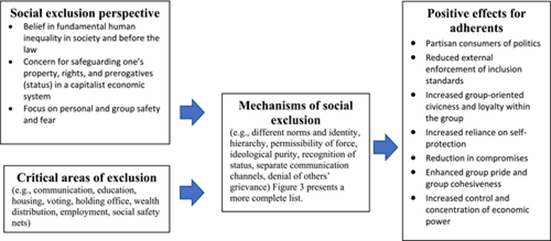

Social exclusion weakens trust between opposition groups, which is replaced by fear. Reciprocity is replaced by retaliation and retribution. Civic bridging groups lose sway and are replaced by groups based on defiant differences (e.g., the KKK or Antifa). Legislative institutions become ideological battlegrounds; institutions meant to exist above the ideological fray (e.g., courts and independent agencies) become politicized. When groups feel that their values and rights are not sufficiently appreciated, they become willing to engage in increasingly extreme action. Diverging communication channels use selectively chosen “facts” which are skewed, and untruths are spread without fear of contradiction. Figure 1 illustrates the social exclusion logic model.

Figure 1 – The social exclusion cycle logic model

Social radicalization

Social exclusion often leads to radicalization in modern societies. When radicalization occurs, adherents are willing to go to extremes; that is, they are willing to go outside the current social network to recreate the social order. Radicalization has four elements. First, there is a desire for a dramatically different agenda or value set to be adopted. Second, there is an unwillingness to collaborate or compromise with those who hold different views. Third, there is a willingness to violate, go outside, or rend apart the current system. Finally, there is a willingness to use force and violence to promote one’s agenda.

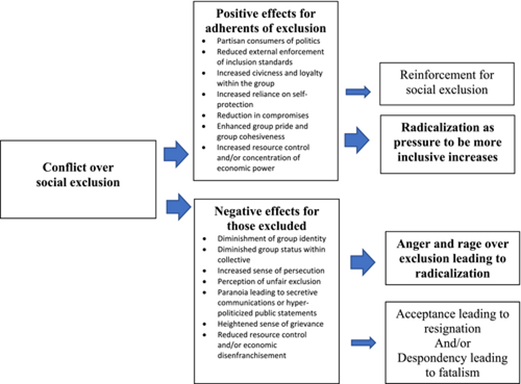

Those who support exclusionist philosophies and policies may become radicalized when their perceived goals are unachieved. They themselves feel victims of “chaotic” or unrestrained forces. Social exclusionists become more strident in their rhetoric and tend to demonize and defame their opponents. They scheme how to gain better, if not complete, control of resources and power with a strong willingness to go outside the current legal, social, and economic systems, which they only partially control. Opportunistic but effective charismatic leaders emerge who support an exclusionist agenda. Even those who support social inclusion are not immune from the siren call of radicalization when they perceive their goals are unachievable. Figure 2 shows the logic model of radicalization.

Figure 2 – The radicalization cycle logic model

The need for anti-extremist leadership in politics, administration, and society at-large

In their 2019 book, cultural backlash experts Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart warn there “are not easy answers” for combating extremism and radicalization. Contemporary researchers in social psychology, extremism, cultism, and social capital theory have many similar recommendations regarding ill-informed citizens who may have become demagogued in media echo chambers and political propaganda.

So, acting to counteract extremism before it causes further radicalization and social crisis is the appropriate, ethical, and humane thing to do. This duty falls on leaders and public managers, who must leverage the extensive historical and scholarly knowledge of the risks of social collapse to minimize—or ideally avoid—its devastating impact.

Public leaders and managers must stand up to social exclusion

The insurrection at the capitol, the breakdown in trust of basic electoral processes, and the hyper-partisanship with audacious pleas to lock up opponents show undemocratic shifts in power are becoming dangerously close. Over time, a pattern of concentrating political control by one party within a state or region reflects growing togetherness locally, but exclusionary otherness beyond. Such patterns are cause great concern.

Public leaders, public managers, and citizens can stand up against social exclusion in everyday life, seek government action against social exclusion, educate children about the dangers of social exclusion, encourage religious tolerance and interfaith collaboration, and encourage organizations to take a responsible stand.

This requires patience, intellectual awareness, intentionality, reinvention, passion, and imagination. In turn, this posture requires an agenda of widely disseminated research, extensive training on anti-extremist actions, and systematic programs supporting democratic and inclusive norms by those in public administration. If large or even small social collapse is to be avoided, anti-extremist leadership and civic activism will matter, and public administration should be a part of that effort.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Social inclusion, social exclusion, and the role of leaders in avoiding—or promoting—societal collapse’, in Public Administration Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3rsMJql