In the past year, President Obama has been roundly criticized by the Republican Party over his use of executive actions. While Obama has claimed that he has taken such actions because of Congress’ inability to act, his critics argue that he is being excessive and maybe even unconstitutional. In new research, Alexander Bolton and Sharece Thrower find that presidents’ use of executive actions became more constrained after World War II – something that they attribute to the allocation of more resources that could be brought to bear on executive oversight.

In the past year, President Obama has been roundly criticized by the Republican Party over his use of executive actions. While Obama has claimed that he has taken such actions because of Congress’ inability to act, his critics argue that he is being excessive and maybe even unconstitutional. In new research, Alexander Bolton and Sharece Thrower find that presidents’ use of executive actions became more constrained after World War II – something that they attribute to the allocation of more resources that could be brought to bear on executive oversight.

American politics has been characterized by divided government and increasing levels of polarization over the last forty years. Partisan conflict has resulted in acrimonious congressional gridlock, leading to missed deadlines, policy uncertainty, and overall dysfunction. These political stalemates within the legislative branch have shifted attention to presidents who seek to change policy on their own where Congress is unable or unwilling to act.

President Obama, for instance, has publically vowed to act unilaterally to bypass congressional stasis on issues ranging from immigration to climate change to student loans as part of his “We Can’t Wait” campaign. As a result, politicians, pundits, and even Saturday Night Live skits have criticized Obama’s use of unilateral action as an excessive and perhaps unconstitutional means of bypassing Congress.

President Obama is hardly the first to face these accusations. The same complaints were common during the George W. Bush presidency and those of his predecessors as well. In fact, the media often portrays these uses of executive power as a common tool of presidents that face an opposition Congress. Despite this pervasive depiction of increased unilateral action during periods of divided government, recent political science research consistently finds the opposite relationship. That is, presidents actually appear to issue fewer unilateral orders when faced with an ideologically hostile Congress, suggesting they may be significantly constrained.

In order to reconcile these two differing portrayals of executive power in new research we explore the question of how the president uses executive actions in the face of legislative opposition by specifically examining one type of unilateral action – executive orders – in a recent paper. In particular, we explore the conditions under which divided government leads to more or less unilateral action.

We argue that the answer lies in the capacity of Congress to constrain the executive. This capacity has changed throughout American history in ways that shape both congressional abilities and executive opportunities. A look at the early twentieth century shows some of these dynamics.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the executive branch underwent a tremendous amount of growth, both in terms of the size and scope of federal activities. The Progressive and New Deal eras brought the federal government further than ever before into the regulation of the American economy and the lives of citizens. New responsibilities were associated with greater levels of spending, new federal programs, new agencies, and increasing numbers of federal employees.

One might expect that the legislature would grow concomitantly with the executive branch in order to better oversee its functions and write new laws for a new type of federal government. Congress, however, remained basically the same during this period. In fact, spending increases on Congress and professional staff assistance were negligible until the mid-1940s.

This left Congress ill-equipped to constrain burgeoning executive power through statutory discretion and oversight. The legislature lacked the proper staff and policy-related information to write constraining legislation. In fact, they relied on the executive branch for these resources. Weak constraints allowed the president to more freely use executive orders, particularly in the face of ideological disagreement with Congress.

By the mid-twentieth century, however, Congress began to pass a number of measures aimed at enhancing its overall capacity by increasing the staff size of its committees, creating procedures and offices to more effectively oversee executive branch activities, and creating independent information-gathering resources such as the Legislative Research Service. Overall, these developments led to significantly increased capacity for Congress as an institutional player in the separation of powers system. As a result, post-WWII presidents became much more constrained in the face of ideologically-hostile congresses.

This suggests that presidents issued more executive orders under divided government in the periods when Congress possessed a lower capacity to constrain the executive branch (pre-1945). On the other hand, during high capacity periods (post-1945), presidents issued fewer executive orders when faced with an ideologically opposed legislature more capable of limiting executive discretion and providing greater oversight.

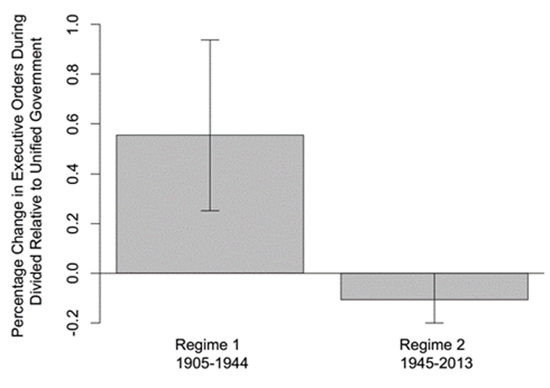

We test these hypotheses by examining all non-ceremonial executive orders issued between 1905 and 2013 and find strong support for our argument. Before 1945, there is a 55 percent increase in the number of executive orders issued each year by the president under divided government (see the figure below). Presidents issue 10 percent fewer orders, however, under ideological disagreement with Congress in the post-1945 period.

Figure 1 – Effect of divided government on executive order usage

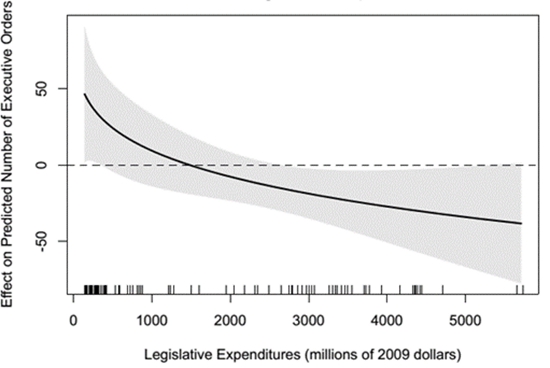

Furthermore, the impact of divided government on executive order use depends on specific indicators of legislative capacity, notably legislative staff sizes and spending on Congress. Figure 2 below demonstrates this relationship. The line in the figure corresponds to the difference in the number of executive orders issued under divided government (relative to unified government) at different levels of legislative expenditures (on the x-axis).

Figure 2 – Effect of divided government at different levels of legislative expenditures

As expenditures on the legislature increase, presidents issue fewer executive orders during periods of divided government. At the lowest levels of expenditures that we observe, presidents are actually issuing more orders during divided government; however, they are issuing fewer at higher levels of congressional spending.

These findings have implications for the way we perceive executive power. On one hand, the president is not an unconstrained political actor that can freely impose his will with unilateral actions. However, while political science studies find that modern presidents are indeed constrained the by the legislature, our research demonstrates that congresses in the past were not necessarily as capable of imposing these constraints on the executive.

Our results suggest that the exercise of executive power is not solely determined by ideological disagreements but is also dependent on the capacity of one institution to constrain another. These results also highlight the importance of examining historical uses of executive power. Our understanding of the post-WWII presidency does not necessarily translate to the presidency of the past. Indeed, a better understanding of these historical presidencies can help shed light on politics as it is practiced today.

The results of our study suggest a number of avenues for future exploration of the historical dynamics of the separation of powers system. Our current work expands the empirical analysis from this paper, examining presidential budget requests and discretion provided to the executive branch from Congress. Overall, this research also raises a number of important questions. How and when did the president develop the control apparatus necessary to deal with the growing executive branch? Do state governments, which vary in legislative capacity levels, show similar separation of powers dynamics? The answers to these questions will help to illuminate the complexities of the executive-legislative relationship in the US and its development over time.

Featured image credit: The U.S. Army (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1DBVlpJ

_________________________________

Alexander Bolton – Duke University

Alexander Bolton – Duke University

Alexander Bolton is a Postdoctoral Associate at Duke University’s Social Science Research Institute. His research interests include executive branch politics and policymaking in the United States.

Sharece Thrower – University of Pittsburgh

Sharece Thrower – University of Pittsburgh

Sharece Thrower is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research interests include American political institutions, separation of powers, and executive policymaking.