In recent years, a great deal of immigration enforcement has moved from the federal to the state level. But how can we explain why some local governments are more or less in favor of immigration enforcement? In new research Jillian Jaeger finds that local governments and law enforcement agencies are being incentivized to help the federal government detain immigrants. She writes that these federal incentives can mean that areas which are more favorable towards immigrants can actually have tougher enforcement policies in comparison to more conservative, but under-resourced, areas.

In recent years, a great deal of immigration enforcement has moved from the federal to the state level. But how can we explain why some local governments are more or less in favor of immigration enforcement? In new research Jillian Jaeger finds that local governments and law enforcement agencies are being incentivized to help the federal government detain immigrants. She writes that these federal incentives can mean that areas which are more favorable towards immigrants can actually have tougher enforcement policies in comparison to more conservative, but under-resourced, areas.

The power to regulate immigration in the United States has traditionally been vested with the federal government. In recent years, however, the federal government has assumed a new direction, pursuing partnerships with local authorities to expand immigration enforcement from the border into the country’s interior. Conventional theories of local immigration policy rely on political ideology to explain why some local governments pursue a pro-immigration agenda while others are more hostile. Yet, the flagship program of these newly fashioned partnerships, Secure Communities, reveals a strong connection between the program’s financial incentives and deportation rates. I argue that this development reflects a shift in local immigration efforts from being ideologically motivated to resource-based.

Secure Communities, also known as S-Comm, is an interior deportation program that depends on local law enforcement to assist Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in apprehending and detaining repeat immigration violators as well as unlawful residents convicted of serious criminal offenses. Despite its termination in November 2014, Secure Communities was seen as a model for how the government plans on moving immigration enforcement forward. Indeed, its replacement, the Priority Enforcement Program, has the same policy objectives and relies on a similar level of local cooperation in order to achieve its purpose.

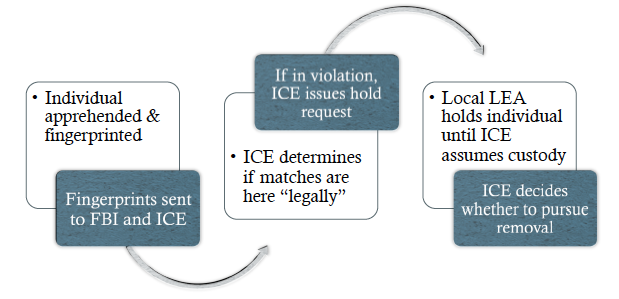

As Figure 1 illustrates, the implementation of Secure Communities intended for local involvement to be minor and without inconvenience. In fact, it was only during the pre-custody phase, in which law enforcement personnel were expected to hold individuals until ICE could assume custody, that local law enforcement agencies (LEAs) were to be called upon for assistance. Technically, this holding period was not to exceed 48 hours after the individual would normally be released; however, reports across the country suggest that ICE hold requests regularly prolonged jail well beyond this timeframe resulting in unexpected costs for LEAs.

Figure 1 – Secure Communities: from Arrest to Deportation

For example, in Washington State the program has increased average jail time by 161 percent, driving up detention costs by about $3 million. In Los Angeles County, California, where immigrants are detained 21 more days than the average inmate, the county pays more than $26 million a year. And, in New York City, ICE detainers led to non-citizens staying, on average, approximately 73 more days in jail than other offenders. What these three cases demonstrate is that complying with an ICE hold request requires financial and physical resources that not every LEA has or is capable of expending.

Moreover, despite ICE’s best efforts to justify the legality of the program, a wave of court decisions in 2014 made clear that ICE-issued detainers could not compel LEAs to hold individuals that would otherwise be released. Despite the 2014 decisions, ICE has effectively achieved local cooperation using financial incentives in the post-custody phase. While post-custody detainment may not have been a planned aspect of the federal-local partnership, it has become essential to S-Comm’s implementation and principal to explaining deportation outcomes.

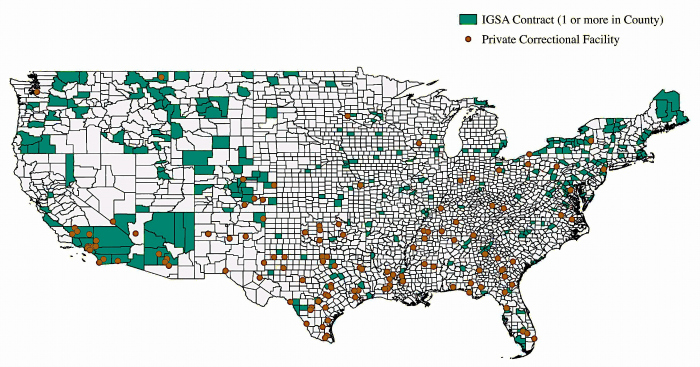

Since 2005, the number of immigrants in federal detention waiting for a deportation decision has doubled to more than 400,000 individuals a year. In an effort to deal effectively with immigrant detainees, Congress mandated that ICE “maintain a level of not less than 34,000 detention beds” at any given time. Yet, ICE owns and operates less than 8,000 detention beds. To overcome this logistical dilemma, ICE entered into Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSAs) and private contracts with local jails and privately owned prison facilities, respectively, to house detainees. Indeed, as shown in Figure 2, the usage of IGSA and private facilities by ICE is widespread.

Figure 2 – IGSA and Private Correctional Facility Locations

IGSAs and private contracts not only offer a solution to ICE’s logistical dilemma, but they also encourage local compliance by compensating private, local, and county facilities an average of $119 per day per bed. The majority of the more than 400 Intergovernmental Service Agreements are direct contracts between ICE and local governments, but an analysis of ICE records shows that 33 percent of IGSAs are for use of jails that are operated by private prison companies. A brief example illustrates this complex web of quid pro quo. In 2014, Eloy, Arizona, agreed to be the financial go-between for ICE and its new privately run immigrant detention facility in Dilley, Texas – yes, Texas. Despite being located more than 900 miles from the facility, the city of Eloy modified an existing IGSA with ICE to expand its contract to cover the Dilley facility. According to an ICE spokesman, the use of Eloy’s existing IGSA allowed ICE to avoid a competitive bidding process, saving them an estimated “18 months to get the facility up and running”. For the city of Eloy, which is promised $0.50 per bed per day, this translates to about $438,000 a year to, as Eloy City Manager Harvey Krauss, puts it, “manage the money”.

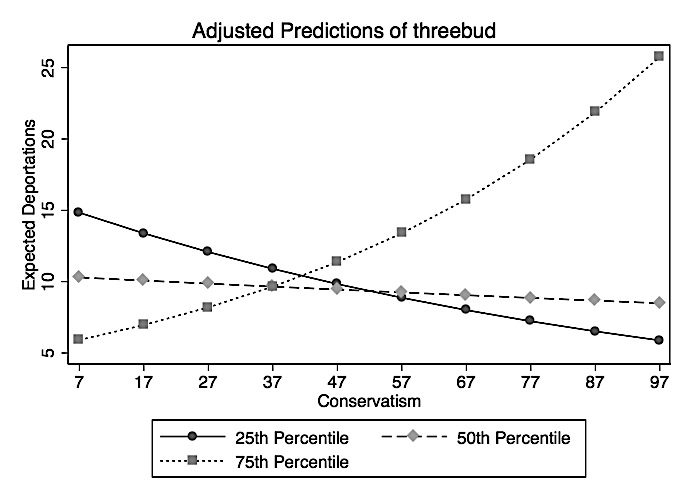

Typically, we assume more conservative localities or places that report higher levels of anti-immigrant sentiment are most likely to pass and implement harsher immigration enforcement policies. Deportation data from Secure Communities demonstrates that this relationship is actually much more complex. While conservative counties are actually amongst those least likely to deport, it is counties with larger policing budgets that report the highest levels of deportation. Similarly, counties with an IGSA contract or a private prison facility report 22 and 15 more deportations, respectively, than counties without. In other words, federally provided financial incentives and existing local resources are crucial to understanding jurisdictional variation in deportation rates.

Figure 3 – Interactive Effect of Law Enforcement Budget and Conservatism on Deportations

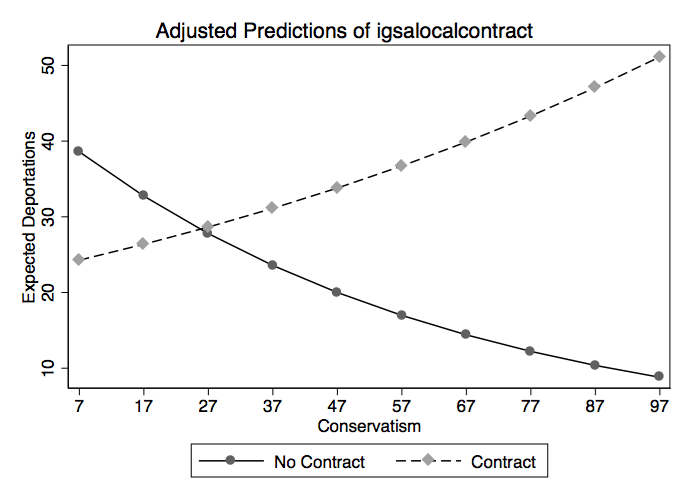

However, if we consider the interaction between political ideology and financial resources, we learn that the relationship between ideology and deportation outcomes is not so straightforward. Figure 3 illustrates that counties with smaller budgets are less likely to deport as they become more politically conservative, but that counties with budgets in 75th percentile experience substantially more deportations as the percentage of Republican-leaning voters increases. As Figure 4 shows, the presence or absence of an IGSA contract demonstrates a similar pattern. The bottom-line is that more conservative counties are more likely to deport, but only if they have a high level of existing resources or an IGSA contract.

Figure 4 – Effect of IGSA Contracts and Conservatism on Deportations

The partnership between federal and local authorities involved in the Secure Communities program demonstrates that discrepancies in local cooperation with federal programs may be due to some jurisdictions having larger resource capacities than others or because certain localities are persuaded to collaborate when financial gains are linked to compliance. In other words, counties that are politically sympathetic to the goals of S-Comm may be unable to assist ICE despite their desire to do so, while counties that traditionally adopt more inclusive measures toward their immigrant populations may be financially motivated to support ICE’s efforts. This finding has strong implications for considering how resources can both prohibit and encourage local compliance with federal initiatives more generally. Furthermore, since detainer requests, the use of IGSAs, and the use of private prisons by ICE are not unique to the agency’s Secure Communities program, we can apply the framework adopted here to better understand the implementation and outcomes of other immigration enforcement programs.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Securing Communities or Profits? The Effect of Federal-Local Partnerships on Immigration Enforcement’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Featured image credit: By Police (Wikipedia Commons) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/22QDeYU

_________________________________

Jillian Jaeger – Boston University

Jillian Jaeger – Boston University

Jillian Jaeger is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at Boston University. Her research focuses on racial and ethnic politics, voting behavior, and the political incorporation of immigrants and minorities in the United States.