As the violent civil war in South Sudan comes to a formal end, peace is made by power-sharing between political competitors. Crucial positions are not elected but distributed through a ‘warlord politics’, providing rewards to those who ‘went to the bush’ to fight the war. Bruno Braak describes this process with the example of a rebel commander-turned-governor in the country’s Western Equatoria State.

On 29 June 2020, President Salva Kiir of South Sudan took to state television to declare the appointment of eight governors to eight states around the country. South Sudanese and international observers have become accustomed to such far-reaching presidential decrees, for instance when he respectively increased and reduced the number of states in the country, or earlier sacked governors unexpectedly. Yet the Transitional Constitution (2011) stipulates in articles 101 and 165 that the president’s powers to dismiss or appoint governors are extremely limited, and governors are to be elected.

The president’s rule by decree is unconstitutional, and leads some to declare ‘The rule of law is on the slope to dying, or if it is already dead it is about to be buried.’

Political appointments in Western Equatoria State

Just how harmful these appointments are becomes clear if we consider in some detail the case of South Sudan’s Western Equatoria State. In April 2010, Western Equatorians had made history when they elected an independent candidate as their governor, Joseph Bakosoro, who proved a strong leader and heralded a period of peace and development. Together with the two other ‘Equatorian’ governors, he pleaded for a more federal system of government and dared criticise the central government of president Kiir. But Bakosoro’s political prominence contributed to his dismissal by presidential decree in August 2015, and arrest in December 2015. Since then, governors have not been elected by the people, but appointed by the president. The most recent appointee for Western Equatoria was nominated by Riek Machar’s SPLA-In-Opposition as per the peace agreement (Article 1.16, Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan).

The man who has now been appointed as governor of Western Equatoria State is Alfred Futiyo (aka Fatuyo/Futuyo), once described as ‘a charismatic, uneducated civilian with no formal security experience’ from Nagero County, on the border of South Sudan and the Central African Republic.

Futiyo rose to prominence due to the incursions by the Ugandan rebel movement the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) into Western Equatoria from 2005/6. The LRA had entered the region with impunity, and locals felt the SPLA national army was doing little to protect them. Local government officials and chiefs organised so-called ‘Arrow Boys’, non-state groups of volunteers armed with any weapon they could find, who took on the LRA in their areas. Initially the Arrow Boys’ effectiveness earned them local legitimacy, and support from chiefs and central government. In 2013 they even received training by US special forces stationed near Nzara to fight the LRA. At this time, the Arrow Boys were scattered, with weak command and control ‘based more on the shared community protection objective than military hierarchy’. They organised when there was a need, and demobilised just as soon to become, again, civilians.

The Arrow Boys changed and became more politicised in 2014–15. Whereas they had initially fought the LRA, in June 2015 they clashed with migrating cattle keepers – ethnic Dinka – from other parts of South Sudan in Maridi and Mundri. Later, there were clashes too between Arrow Boys and SPLA troops across Western Equatoria and in the state capital Yambio. During this same period, Alfred Futiyo competed with a handful of others to organise the scattered groups under a single chain of command. Different names came up: the Revolutionary Movement For National Salvation (REMNASA), the South Sudan’s Peoples Patriotic Front (SSPPF), the South Sudan National Liberation Movement (SSNLM). Within those groups, too, there was ample intrigue and competition.

By late 2015, Alfred Futiyo claimed to be in charge of some 10–17,000 troops and he declared his allegiance to the SPLA-In-Opposition (IO) of Riik Machar becoming ‘major-general’ in charge of the SPLA-IO’s ‘Gbudwe division’. The low-point in the relations between Futiyo and government arguably came in November 2016 when Western Equatoria’s governor at the time, major-general Patrick Zamoi, placed a 1 million SSP bounty on the head of Futiyo, saying that the time for peace talks and amnesty was over. To men with hammers, problems look like nails.

The civil war intensified and civilians bore the brunt of it. There were murders, rapes, pillaging and forced recruitments of minors. In Uganda I interviewed several former combatants, young men who had fought with Futiyo and now lived in a refugee settlement. A 26-year-old man recalled: ‘The suffering we got in the bush was too much. People used commands and if you did not comply with them, you were imprisoned or even killed.’ Another 21-year old had no illusions: ‘Our leaders started the war and pushed it to the youth.’

The civil war (2013-present) has displaced over four million South Sudanese, and cost the lives of an estimated four hundred thousand people. Despite peace-on-paper, the country remains desperately divided and clashes remain common. There is some political progress, but it is bitter: back in power are the same President Kiir and First Vice-President Machar who started the civil war in 2013, and whose enmity dates back to the 1990s. Like those two most powerful men, Alfred Futiyo built his career by the gun. His appointment sparked debate among Western Equatorians on social media.

Some worry whether this ‘divisive and illiterate’ man associated with wartime atrocities can bring back peace and unity to their beloved state. Others are hopeful that Futiyo can bring stability and progress. It is too early to say what his tenure will bring. But even if he proves to be a good governor, a fundamental problem remains.

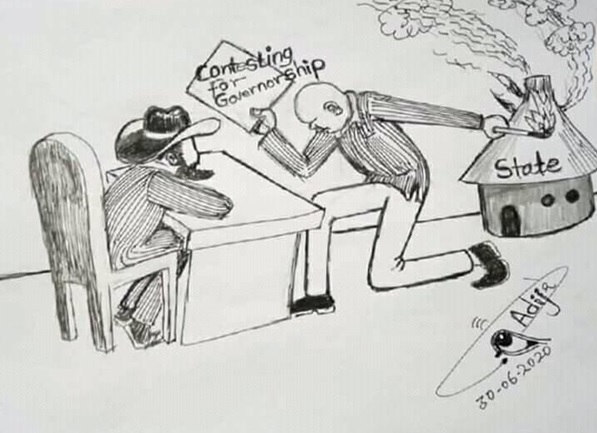

Futiyo’s appointment illustrates that in South Sudan the violent are rewarded. As a friend of mine summarised: ‘The only way we can get these posts, is by entering the bush.’ The system is plain: Go ‘to the bush’ to fight/rebel violently, perform loyalty to Kiir or Machar, talk peace and ‘power sharing’, and get a position.

This cynical system of ‘warlord politics’ was described aptly by Alex De Waal in writing about Darfur, where ‘violence has been used not to achieve military victory but to raise actors’ status in a patronage hierarchy’. South Sudan is by no means a lawless society and many disputes are resolved quite successfully at local levels. But a fish rots from the head down. These sorts of peace deals reinforce impunity at the top and reward, legitimise and perpetuate violence. The price for this politics is meanwhile paid by those with the least control to change it. In the words of the 26-year-old former combatant: ‘I hear about peace, but I have not experienced it. What we always get is suffering.’

Photo: Juba, South Sudan. UN Photo/Paul Banks.