In this extract from their evidence to the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology, Dr Mike Galsworthy (left) and Dr Rob Davidson explore the relationship between EU membership and the effectiveness of science, research and innovation in the UK.

In this extract from their evidence to the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology, Dr Mike Galsworthy (left) and Dr Rob Davidson explore the relationship between EU membership and the effectiveness of science, research and innovation in the UK.

Collectively, the EU remains the world leader in terms of its global share of science researchers (22.2%), ahead of China (19.1%) and the US (16.7%), according to Unesco’s Science Report (released last month). This would be a fairly moot bragging point, were it not for how the EU science programme has managed to network the European countries into a collaborative engine which serves as a hub of science in the wider world. This, in turn, has benefited UK science prowess demonstrably.

The EU is now a community of scientific talent which can flow between countries without visas or points systems and which can assemble bespoke constellations of cutting-edge labs, industry and small businesses to tackle challenges local and global. Across the 500m populace of the EU (plus the Associated Countries which buy into the EU science program), there is a capacity to pick’n’mix the best labs to do the job – and apply for funding from a single source. Given that the European Research Area produces a third of the world’s research outputs, this communal spirit provides a powerful environment to combine leading players across borders to common advantage. So large is the programme that top teams in 170 other countries in the world are easily taken on board as secondary participants. This, in a nutshell, is how a collection of countries converts its critical mass into a critical research advantage, globally.

Twenty-first century science often has to go big to go small and increase the resolution of our understandings and capacity. Developing new nano-materials or discovering ever-rarer particles often requires more expensive machinery to establish more extreme conditions. In health, identifying ever-smaller contributory effects (e.g. multiple interacting genes in disease development) requires ever larger sample sizes of patients. Increasingly complex models require larger collections of expertise and shared resources. This is more than an appealing narrative: The drive to big networked science is also borne out in the data on the rising internationalisation of science and the associated impact. Below we demonstrate how the international networks uniquely supported by EU funding have driven the UK into global pole position for productivity.

Increasing internationalisation

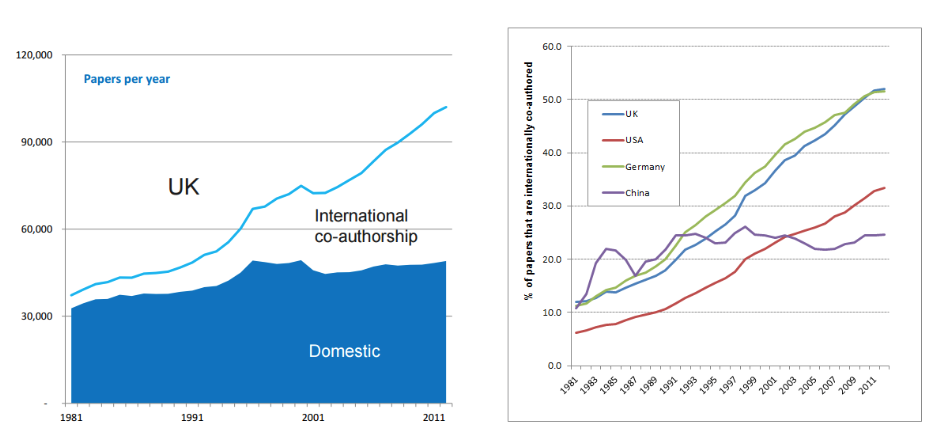

Since the 1980s, global research has become rapidly more international. The prevalence of scientific research papers co-authored by researchers from more than one country has risen sharply. However, some countries have seen this increase more than others. Since 1981, the UK has risen from 15% of its papers being international (and 85% domestic authors only) to over 50% international today. In fact, almost all the growth in UK output is in the form of international collaborations.

This rate of increase can be compared to the US, which has seen a rise in internationally co-authored papers from 6% in the 1980s to 33% currently.

Internationalisation and impact

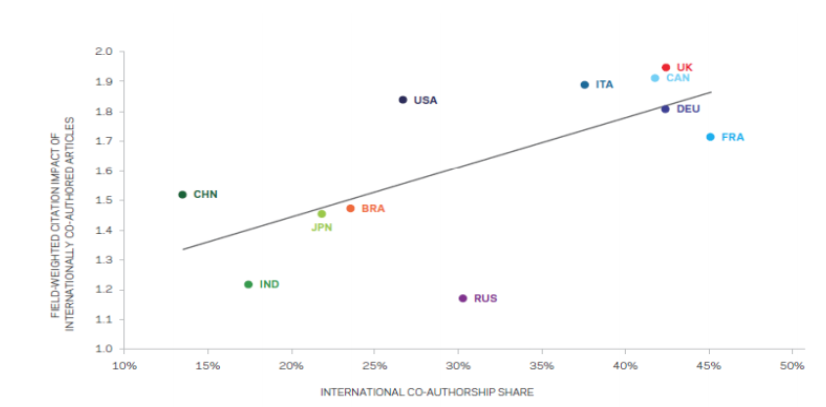

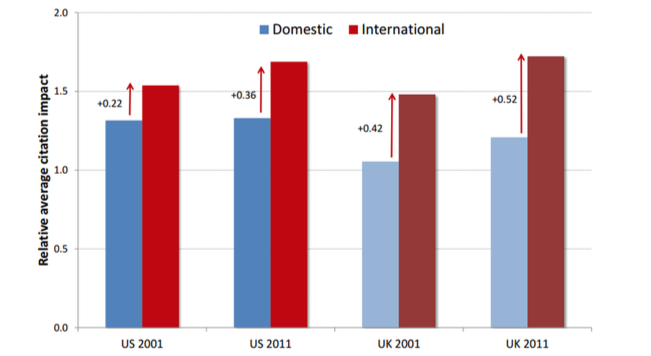

Multiple sources have identified international co-authored papers as having substantially higher impact than domestic-only papers.

Reproduced with kind permission from Dr Jonathan Adams.

The UK’s strong lead over the US on proportion of international output interacts with the added impact of international output – resulting in the UK science base now measuring as more productive than that of the US. This is despite the US’s domestic-only papers showing more citation impact than UK domestic-only papers. International collaborations give the UK the research quality edge.

Reproduced with kind permission from Dr Jonathan Adams.

How much of this increase in internationality can be attributed to participation in the EU science programme? Approximately 10% of UK public funding for science came from the EU during 2007-2014, this amount has been rising sharply recently and, pertinently, Horizon 2020 funds are predominantly for international collaborations. Of the UK’s international collaborations, 80% include an EU partner. Therefore, it is not too adventurous a conclusion to state that participation in the EU science programme looks highly likely to have helped the UK science base become more productive than the US.

Other benefits of a pan-European science programme to EU and UK productivity

- Beyond the cross-border collaborations themselves providing more impact than domestic-only work, there are multiple additional properties of a pan-European science programme that confer increased science capacity and productivity to its members:

- The presence of a pan-European fund helps prevent duplication of activity.

- The spread of good practice is facilitated 1) by collaboration and researcher interactions and 2) by adoption of successful policies from one country (e.g. open access, open data) into a funding body present in multiple countries.

- Such a large comprehensive programme covering the gamut of research and innovation areas sets a common framework for funding categorisation and comparisons; a spine against which national funding schemes can be benchmarked.

- A single one-stop shop for international collaborations removes a vast amount of bureaucracy that would be incurred otherwise. Without the EU common pot of funds and common administration, a UK lab looking to partner with, for example, teams in four other countries would encounter serious trouble in finding full funding. The UK government (or any other) would be unlikely to fund a five-way collaboration on which the UK partner undertook 20% of the work. Similarly, all five partners attempting to obtain matched funds from their governments means five times the administrative loads, aligning five timelines of funding applications and work, and five times the jeopardy in getting the monies through. If each of the five applications had a 20% chance of success, then the overall chance of getting funding for all five partners would be 0.25 = 0.00032. The EU, however, regularly funds teams of many partners. This is because the governments of the EU members and associated countries have committed money to a common administration that can choose to fund constellations of labs, regardless of team composition, based solely on competitiveness of the proposal.

“Brexit” and free money for science

“Our current assessment is that leaving the EU would be likely to impose substantial costs on the UK economy and would be a very risky gamble.”

Analysis by economists at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP)

Stocktaking the current benefits of EU membership to UK science is not enough. This House of Lords inquiry will be used to inform the debate on whether to stay in the EU or leave. To adequately address the role of UK science in the debate, we must compare realistic models of UK science continuing within the EU against realistic models of UK science moving to a position outside the EU.

As an analogy: When evaluating the utility of any new drug or treatment, the medicine at hand must be compared not only with a placebo, but also with the best competing medicines on the market. In the case of EU membership, we must compare the current trajectory within the EU against more than flat-cash reimbursement of EU funds through UK funding mechanisms (placebo). We must compare UK science in continued EU membership with the most seductive alternatives being offered on the market.

To summarise those alternatives; we, have widely encountered two notions:

Firstly, that because the UK is a net contributor to the EU budget, then the UK could leave the EU and the surplus money gained from the transition could be channelled into research and innovation. In short, leaving the EU frees up money for UK science.

Secondly, that because non-EU countries such as Norway and Israel can have full participation in EU science programmes such as Framework 7 and Horizon 2020, therefore there is no threat to the UK’s relationship to the EU science programmes continuing as is. On leaving, we simply buy back into EU science programme participation as the other countries do.

Combined, the claims amount to an appealing package: On leaving the EU, the UK could continue reaping all the benefits of full membership on the EU science programme whilst having significant extra cash-in-hand to boost public investment in R&I at the national level.

Both these notions are dangerously – and demonstrably – misinformed.

The availability of money on a departure from the EU

There is a claim by the campaign Vote Leave (which use the slogan “Vote Leave – take control”) that a Brexit will free up money for R&I investment11. This claim is based on the UK being a “net contributor” to the EU budget as a whole. The size of that net contribution varies, but according to analysis by economist Roger Bootle in his 2014 book “The trouble with Europe” (which, incidentally, contains no analysis of EU research and innovation in its 201 pages), the UK paid a net £9.6bn into the EU in 2012, about 0.6% of nominal GDP.

Models of impact to the UK economy on Brexit vary. The Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) calculated the UK could suffer income falls of between 6.3% to 9.5% of GDP under a pessimistic scenario. CEP calculate loses of 2.2% GDP under an “optimistic scenario” (a free trade agreement with the EU). The think tank Open Europe calculate UK GDP could be 2.2% lower in 2030 if Britain leaves the EU and fails to strike a deal with the EU. In a best-case scenario (liberal trade arrangements with EU and globally, with large-scale deregulation at home), Britain could be better off by 1.6% of GDP in 2030.

Importantly, even the more optimistic assessments of the UK’s economic performance following a Brexit (such as the “best case” +1.6% GDP increase by 2030 by Open Europe) all analyses model an immediate loss in GDP for the transition years following a Brexit. The size of that loss is substantially larger than the current net contribution of the UK to the EU budget. The triviality of the UK net contribution relative to the greater economic forces around transitioning out of EU membership have been noted by Bootle: “These are not the sort of sums on which the fate of great nations depends – nor on which momentous decisions about EU membership should be made.”

Therefore the attempt to financially gain in the short term via a Brexit is akin to killing the goose that lays the golden egg. It is a sure-fire short term loss, wiping any free money for R&I investment until at least a decade down the line – according to the most optimistic scenarios. This strongly counters any claim that voting to leave the EU provides immediate funds for a shot in the arm of national science. The extra money simply will not be there for science as the UK economy is hit by huge transition costs. Even if it were the case that there were free cash-in-hand on a Brexit, the individuals offering this money to science (as part of their campaign) would have no power over its allocation. None of them have any track record in science policy or impact on national science budget allocations. They are simply in no position to offer money to national R&I – even if that money were available.

It is worth taking a moment to consider where the UK’s net contribution actually goes. The UK net contribution (and similarly, the net contributions of the other wealthier countries in the EU, such as Germany – which contributes the most) has risen in recent years due to the EU’s expansion eastwards, taking in new member states that are less developed than western Europe. Regional development funds are being used to support their development. A huge transition from the FP7 to the Horizon 2020 timeframes concerns the use of regional development funds alongside the science programmes to support research and innovation capacity building. So while eastern (and southern) Europe’s under-competitiveness does not interfere with the EU’s criterion of funding “excellence” in science (a decision which benefits the UK greatly), nevertheless, it is important that those EU countries which came into the competitive funding environment late receive adequate support to be competitive. Otherwise brain drain and disillusionment will drop capacity in those regions and for the EU overall.

Therefore, the new focus of the Commission to dedicate regional development funds to R&I means that the whole EU ecosystem of science is strengthened in all parts. The UK, as the EU science programme’s leading player – benefits strongly in the long run when it can participate in and lead (more than any other country) ever more capable teams from an ever stronger region. Much of the “net contribution” being promised by Vote Leave to UK R&I is currently deployed to strengthen the pan-EU science hub that boosts the UK’s global leadership in science. Therefore those monies are already being strategically invested in the UK’s R&I future. Ultimately, we see further by standing on the shoulders of a giant.

A case study of Switzerland as a model for UK science outside the EU

Fortunately, this discussion is not purely hypothetical, but rather based largely on the precedent of Switzerland’s relationship with the EU science programme. Given Switzerland’s high competence in science, geographical location in Europe, non-EU status and political difficulties with issues of EU immigration – Switzerland is a helpful model for the UK’s re-negotiation of science programme membership following a Brexit:

Synopsis of the Swiss-EU science story

1. Switzerland is not a member of the EU but since 1992 has obtained full access to Framework Programmes, as part of agreements that also guarantee free movement of persons, contributing to the FP budget alongside other EU members.

2. In 2014, a popular vote to limit mass migration was passed by a margin of 50.3 to 49.7%

3. The Swiss government was then unable to commit to ratification of a free movement accord with Croatia.

4. Switzerland was suspended from access to Horizon 2020.

5. The Swiss government was forced to replicate at national level a temporary programme to replace immediate access to the ERC programme and subsequently negotiated limited access to H2020, with much reduced access to programmes, exclusion from the new SME Instrument and loss of ability to coordinate collaborative research within H2020. This is reliant on continued freedom of movement. Switzerland also funds Swiss participants in EU collaborative programmes directly at national level, requiring parallel domestic administration and an agreement to accept all funding decisions made in Brussels, effectively losing control of its national science budget.

6. The Swiss were also not included on Erasmus+. They chose to ensure continuation of the scheme by paying nationally both for students leaving and for those coming in (i.e. paying double what they would as a member of the international programme).

7. Negotiated access to H2020 will end in 2016, when Switzerland must either ratify the Croatia treaty or lose access to H2020 plus risk its bilateral trade agreements with the EU.

8. Switzerland must contribute to H2020 based on GDP and population and has no role in developing funding topics.

This case study of Switzerland represents an instructive set of circumstances for the UK with regard to Horizon 2020 access post-Brexit. Switzerland’s current participation is dependent on free movement. Should the UK leave the EU and restrict freedom of movement, it will have no access to Horizon 2020 beyond third country status (Afghanistan, Argentina etc.). However, as detailed further on, the sheer size of the UK causes problems for re-joining the EU programme after rejecting the EU.

The UK must consider that a withdrawal from the EU, followed by Horizon 2020 ‘buy in’ such as that of the Swiss model, will require continued EU budget contribution. Switzerland makes a contribution to the Horizon 2020 budget based on its GDP and its population, but the UK may have to pay more than its current contribution and/or accept limited involvement, due to its size, so as not to be so overtly disruptive (without the counter-balance of net contribution investment into less competitive regions). It will also have to follow Switzerland in creating domestic administration structures for programmes where it will fund UK participation in Horizon 2020 collaboration from domestic budgets. This has the double disadvantage of replicating a complete administration structure in the UK that operates on EU financial and legal rules without any role in creating those rules, and it must agree to a single evaluation decision made in Brussels to avoid damaging the partner-worthiness of UK participants with an additional UK level of evaluation.

The requirement to agree to implement funding decisions made in Brussels will ensure that the UK cannot control budget allocated to such collaborations. This creates a scenario in conflict with claims by anti-EU groups. The UK will still be contributing to EU science financially, it will have no control over domestic budget for collaborative research and it will have to sustain a parallel administration structure. This combination of factors means that the UK cannot make a simple financial calculation on financial contribution to EU science nor estimate how much it would retain to fund UK research post-Brexit.

Important considerations pertaining exclusively to the UK’s relationship with the science programmes must be addressed upfront. Unlike Switzerland, Norway, Turkey or any of the non-EU countries that hope to become full Associated Countries on the EU science programme – the UK has a lot more to lose. The UK is currently a full member of the EU, meaning that it has a political say in the development of the science programme. It is also the leading player on the EU science programme, winning more grants than any other country during Horizon 2020 so far. That means it has overtaken Germany, which was the leading country on FP7 (see Figure 4 above).

This combination of the political input (and the UK has, due to its population size, the third largest delegation to the European Parliament), and the UK’s science prowess means that the UK has the kind of status and power on the programme that no non-EU participating country has. These other countries are easily absorbed into the overall programme at a cost. Whether they are EU members or not, they would not command much of a political say on overarching science direction and management. This commanding position for the UK means that, on Brexit, a buy-back into the programme as a full Associated Member would have several major flaws:

- The largest player on the programme would have no political say about its formation.

- Playing by the same rules as others means a 12% contribution of funds for 16% gain of competitive funds – a very damaging ratio to the other countries given the UK’s size, given also that it is no longer a net contributor to an EU budget and therefore not supporting the R&I of other EU countries.

- The threat of the UK changing its immigration policies at any stage offers major disruption to the programme, which must respond according to the precedent with Switzerland.

In conclusion, the UK acquiring full Associated Country status on Brexit is not an option. The EU has already introduced and used the concept of Partial Association with Switzerland and would do the same with the UK, tailoring a deal to maximise its own interests.

The impact on Swiss science of a partial access deal

Although it is early days in Horizon 2020, nevertheless, data available clearly show the disruption caused to Swiss science performance on the EU program (Figure 5). The uncertainty and renegotiations, despite clawing back participation on areas of the program critical to Switzerland’s interests, has taken a marked toll.

Swiss participation in H2020 and financial benefit has declined significantly, despite negotiated access. The above graph suggests a drop in participation by over 40% for Switzerland – highlighting the cost of renegotiation confusion even for a highly-competitive scientific community. Swiss sources (private communication) report a declined trust in Swiss research partners and rapid reduction in their engagement in collaboration – the Swiss science sector is reliant on immigration and its innovative performance is likely to decline, particularly if it must completely exit Horizon 2020 membership in 2016.

Retaining EU membership: Is the EU headed in the right direction for UK science?

Figure copied from Science Europe & SciVal report (2013). “Europe” denotes all countries that paid into the FP7 science programme (ie. 27 member states plus 14 associated countries)

The UK is currently in the driving seat of a global hub of research excellence that is larger than the US in output size, growing faster than the US (see diagram above), and with a far higher rate of international collaborations at a time when the impact of international collaborations are bringing increasingly high impact.

From Eurocracy to leadership

However, the benefits of the UK remaining within the structure of the EU go beyond the clear internationalisation-impact dynamic. The increasing competence of the EU in science management is beginning to be felt. Whether one considers the bold commitment to increasing science investment despite shrinking overall budgets, a holistic and well-articulated vision for science, closer democratic accountability for the budgeting and priority-setting within science, success in linking universities with small businesses, open data, bold infrastructure, the European Research Council and plans for a similar innovation council, or newfound transparency around its science programme outputs – it is clear the EU has discovered an appetite for science leadership. The body has transitioned from a painful bureaucratic funder poorly copying a US lead into a true leader confidently setting its own agenda. UK politicians even act as a barrier to UK science’s capacity to fully harness the benefits of the EU. The low participation rate of UK SMEs on Horizon 2020 relative to our universities is directly attributable to very poor advertising through channels such as BIS and Innovate UK.

Any pride that British politicians may feel about the quality of British science in comparison to other countries in the EU should have their mood strongly tempered by the realisation that in the eyes of many British scientists, the EU is stealing a march on the UK in science policy leadership. New directions and capacities that our UK scientists argue for are now rapidly adopted within EU thinking, whilst in the UK, common knowledge about core needs (e.g. a funding increase to a 3% target) often circulates perennially with inaction by the parties in power and their appointees.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.

Dr Mike Galsworthy is an independent consultant in research and innovation policy and a visiting researcher at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Dr Rob Davidson works as a Data Scientist for the academic online journal Gigascience. Previously he worked as post-doctoral bioinformatician at the University of Birmingham. They lead Scientists for EU, which launched the day after the UK general election when the Conservative win ensured that there would be a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU.

First of all, I’m glad scientists4EU have finally confirmed that Horizon 2020 etc is open to non-EU countries (e.g. Norway, Israel etc).

The availability of money on a departure from the EU …..

Selective use of Leave scenarios, i.e. the Policy Network paper (the clearly non-neutral Pat McFadden with some speculative assumptions), Open Europe (The PM’s own pet EU think tank). I could dig out loads of optimistic scenarios generated by Leave side, all as equally valid (which is to say “not very”). Or we could recognise that the plan is to Leave the political structures of the EU, but retain single market access = neutral in economic/trade terms.

Similarly, regarding UK contributions, we’d probably make some savings on Leave, but its trivial in the scheme of things = essentially neutral. We should ignore noise from Vote Leave.

Regional Development Funding – this is a long way from the question of funding science. Even so, EU membership is again not a pre-requisite for this. For example, Norway pays EEA grants and its own Norway Grants, funds that go directly to Eastern Bloc states (not via EU).

Broadly, I’m in favour of maintaining science program funding and Eastern Bloc development funding. But ultimately this is UK taxpayers money and it is to them you should make your case. Arguing that we should be in the EU to take that choice away from taxpayers is undemocratic. Moreover, such an overtly partisan political approach by scientists4EU risks alienating UK voters/taxpayers and damaging the reputation of science in the UK. Your approach is making me question this science funding – and I’m much more pro-science and development funding than the average voter.

Switzerland ….

You discuss Switzerland’s recent problems with Horizon 2020. However, its clear that these problems arise from Switzerland’s decision to adopt immigration quotas. If the UK tried to adopted immigration quotas within the EU, it would face the same problems (and a whole load of additional sanctions & fines). Membership or non-membership of the EU is not the issue here.

Leaving the political structures of the EU but retaining single market access means retaining Freedom of Movement – fine by me and its seen as a positive by many. Freedom of Movement has been wrongly conflated with immigration; fortunately there are practical measures that can be taken to mitigate large-scale immigration of low-wage labour without removing Freedom of Movement.

What does concern me is the EU’s use of science & trade as coercion and the EU’s willingness to override democratic consent. This post by another blogger articulates my thoughts better than I can on immigration & democracy: https://medium.com/@WhiteWednesday/we-need-to-talk-about-immigration-3542d0687f6a#.g08etdi67

Finally …

Your argument concerning the political say in Brussels is both dubious and troubling. The non-EU countries get a pretty good share of the funds when you consider their relative populations. As I understood it, funding decisions are made on the merits of the case (as it should be for any scientific program), not on political considerations.

Fundamentally, there is no reason why political union should be a pre-requisite to scientific collaboration. If you are really claiming that political union is the price we have to pay for participation in these programs, then I believe I speak for the great majority of UK public in saying:

(i) any programme that is so overtly political has dubious scientific credibility

(ii) that’s too high a price to pay; we should withdraw from Horizon etc and spend it on R&D as we see fit

in addition to the above reply, its not mentioned that academic science at universities in this country are flooded with european workers (all being paid from uk tax payers money) because they all speak english as a second language and the universities are after as many international students as they can in order to receive their higher fees.

its often the case that most workers in university groups dont come from this country, some groups are entire comprised of europeans and through their vast numbers excluded british students from having those jobs. The european workers are not the brightest and best, theyre mainly just either coming here from a much lower wage country or staying on after studying here.

The traffic is mainly all one way as uk students cant work in another country unless they speak the language (most europeans are taught english as their second language from school age) and the drop in wages in poorer countries.

You are wrong in a number of key respects. EU students (or ‘workers’ as you call them) do not exclude any British students from higher education at all. Students are ‘selected’ and offered places on higher degrees and research positions based solely upon the funding available (the majority of which is from the British government and predominantly disbursed through the research councils or higher education funding councils), or industry (including European Industry) and a significant (but relatively small) additional element is from charity organisations (e.g. the Welcome and Leverhulme Foundations). Students compete on the basis of quality alone for those funded places or research contracts. A British student who meets the experience, training and other quality criteria will get an opportunity to continue their training and career in science, if the funding is available. Students are selected on the basis of their ability and potential in competition with others, to restrict access to that competition from high quality European nationals will require research leaders to select further down the list – there will be an inevitable deterioration in standards. If any British student fails to succeed in finding a place, it is only because there is no funding available for their chosen option or they are uncompetitive. Membership of the EU has only increased funding resources for further degrees and research positions considerably increasing the opportunity for British students. Regarding British students studying for higher degrees in Europe or looking for junior research positions to advance their career, you are absolutely wrong. Language is not a barrier in modern Europe, many British students do study abroad for higher degrees (and very successfully) and there are many post-doc’s and related junior research staff advancing their careers in Europe in order to get some of the best training and experience anywhere in the world. I know, a number of my own students and postdoc’s have done exactly that; I also know many other research supervisors across the UK for whom the same is true (it is indeed very common in science). many of the mechanisms for enhancing the opportunities for British students to enhance their career and help them with their first foot on the career ladder are dependant upon membership of the EU funding systems that provide for this. All the countries outside the EU that do fully subscribe to this membership either have a limited access to it, or have to accept the same requirements (free movement of people, financial contribution to the EU etc.) as any other member state, or be excluded.

If we leave the EU, the only way the loss of opportunity for young British scientists could be made up is with increased funding from the British government, along with all the other calls on its resources arising form loss of support from Europe (farming, healthcare, social services, regional development, servicing the depressed economy etc. against a background of a negative balance of payments against the current account, a government with an ideological belief in austerity and the most optimistic forecast for the economy indicating a short to medium term shrinkage. It may be that ultimately the economy recovers successfully, by then we will have lost an enormous potential in this generation of young scientists. Another point you haven’t considered, scientists follow the funding, it is a necessary element of career advancement (if you don’t have funding, you can’t do science). If the opportunities are rosier in Europe after a vote to leave the EU, many experienced scientists will also leave the UK. The people this affects most are the most successful, i.e. the most productive, innovative and the those who contribute the most to the future wellbeing of our economy.

I can only guess from your rather theoretical approach to how peoples career and therefore lives hang in the balance from vast numbers of overseas job applicants, that its been sometime since youve had to face that reality.

By allowing vast numbers of European workers to apply for uk research jobs all its done is allow academic employers to find European applicants with more technical experience or slightly more relevant experience rather than train an equally capable uk applicant. And of course, you can always find someone more experienced for any job if theres the whole of Europe or the world to chose from, it doesnt mean theyre better and those who dont get the job are worse (or ‘uncompetitive’ as you put it), but rather the odds have been stacked against uk applicants through vast skilled labour oversupply.

Its baloney to say that there would be a drop in standards as anyone who’s been involved in recruitment will tell you there are large numbers of skilled and motivated applicants from this country alone for science vacancies.Employers always complain that theres too many applicants with very few exceptions and that will continue as graduates and phd’s are produced in large numbers every year.

Most European workers filling large numbers of university jobs (and i’ve worked with alot of them) are not professors, the brightest and best, filling vacancies no-one wants to do or any better than uk applicants, and indeed by training more of the graduates who live here, its more plausible that uk commercial and academic science sectors (not to mention intellectual property) would be better off.

You also cant deny that universities are full of european workers and for every one of them has taken a valuable skilled job, thats a job someone from the uk could and would have done.

Its also not considered that if a european worker that is funded by the uk taxpayer through research councils funds, moves back to another country then a not inconsiderable amount of wealth (and scientific training) is taken out of the country.

Your speculation on ‘scientist flight’ is the same as what was threatened from the banks about ‘banker flight’. Moving everything to any other country is a last ditch option for most people and any experienced academic would just get a job in the commercial sector instead. If an academic is forced to take that option then it probably shows that they are operating in an academic bubble kept alive through public funding (which ive seen time and time again) and their research field and career produces nothing of any value in the real world.

Anyway, i’ve worked in universities for years as you can see by the amount of europeans filling up 50% or more of a lot of university groups here compared to the trickle of brits whove gone to study or work in europe, the traffic is largely one-way (which is fuelled by english being a second language to a lot of european workers) and the vast majority of uk students and scientists dont work abroad and dont see any benefit, which they soon find out when they end up competing against european workers at interviews. When confronted with that reality on the ground, of skilled labour oversupply from often much poorer counties, your lengthy explanations about the benefits of travel etc. are rather meaningless.

To qwerty:

Figure 1 of this Royal Society report (link below) shows that your claim about the fraction of non-UK academic university staff is just wrong. 72% of the academic staff in british universities is british. 49% of PhDs are british (only 14% of PhDs are actually from the rest of the EU). So, saying that brits don’t make up the majority of academic job is not correct (only 16% of academic jobs are taken by EU non-UK researchers). You are just trying to scare people. Also, maybe you did not realise, but these EU academic “thieves” do pay taxes too, just saying…

https://royalsociety.org/~/media/policy/projects/eu-uk-funding/phase-2/EU-role-in-international-research-collaboration-and-researcher-mobility.pdf

PhD students pay no tax and post-doc’s are paid by public funds anyway!

The only academic staff paying taxes are permanent staff employed by the university, professors and lecturers, who are being supported by the students getting in to years of private debt (around half of which will be written off then paid by the government/uk taxpayer).

EU workers are part of the problem with universities seeking to pull in large numbers of oversea’s students and workers to the uk, because universities have undergone vast over-expansion. In the last group i worked in more than 75% of its post-doc researchers were European workers and about half the PhD students were from other countries. This isnt uncommon and ive visited a number of other groups who employ virtually no-one from this country.

Even using your figures, more than a half of the PhD opportunities are being taken by non-uk graduates on around £50k (for the 3 year project) and a quarter/third of all academic staff being non-uk nationals on at least £30k/year for each postdoc, there are no shortage of applicants for these jobs and it amounts up to hundreds of millions of pounds in funding and training given to overseas workers; vasts amounts of money and opportunities that could have been given to equally capable uk graduates.

Perhaps the most alarming fact is that through giving most of the PhD opportunities to non-uk graduates and training up the rest of the world, the future situation will only get worse as they will either go on to take the few post-doc jobs in the group when they finish, uk commercial jobs, or could very well end up in rival research groups or rival commercial jobs in their own country. This is a problem that most group leader academics seem to be blissfully unaware of because theyre in well paid permanent jobs and the mass oversupply of overseas graduates and workers which theyre training doesnt affect them at their level.

Its churlish of you to use the word thieves to try and characterise my response on EU workers as the point was and is that as we are losing £30 million/day to the EU, money we get in science funding should be used directly in the interest of the people of this country by giving the valuable skilled science jobs and phd science training to uk graduates rather vast amounts of workers from the EU and other countries, nearly all of whom are inherently no better than the uk graduates that they displace.

So much ignorance in this article that makes me sick..this is stupid propaganda..leaving the EU, as has happened, will make the UK much poorer and less competitive and less suitable for international investments that money for UK research will be less (as matter of fact).

Speaking as one who lives in Switzerland, I was disgusted by the behaviour of the EU, trying those bully tactics of kicking Switzerland out of the education funding about the day after a democratic vote was taken. I’m baffled that anybody would want to be part of such an organisation other than from fear, which was the point of the EU’s action.

One could see that long term if the vote was implemented at national level and if it were done in a way that offended the EU, then all bets were off in terms of agreements between the two, but over two years later, it still hasn’t been implemented.

I was nothing but impressed by the smooth and reliable way in which the Swiss reacted through their own funding. And if I were Swiss I’d be shaking my fist at the EU and saying ‘Think you can bully us like that? F*ck Off’!!

There is still good science being done in Switzerland, without the massive red tape of the EU which makes the conducting of science secondary to form filling in, and I suspect less of the projects funded are scams.

Masters tuition fees in Leiden 2000 Euros in EU 19000 Euros non EU I would laugh at the view point that people voted for Brexit ‘ for their children ‘ if I didn’t feel sick .