Why do phone and online polls diverge so greatly? Matthew Goodwin discusses why the figures for Leave and Remain differ according to the polling method and argues that we need to approach results with caution. He also looks at how important Boris Johnson’s intervention will be.

Game on! Britain’s referendum on its continuing EU membership is scheduled for June 23. So how are the Remain and Leave camps doing – what is the state of the race so far?

Well, it might be crunch time but there is also considerable confusion in the polls. Let’s take a step back and look at what is actually going on below the surface. As I wrote for The Times Red Box this week the picture is far from clear. The headline, take-home point is that the polls conducted online tell a very different story about what is likely to happen to the polls conducted via telephone.

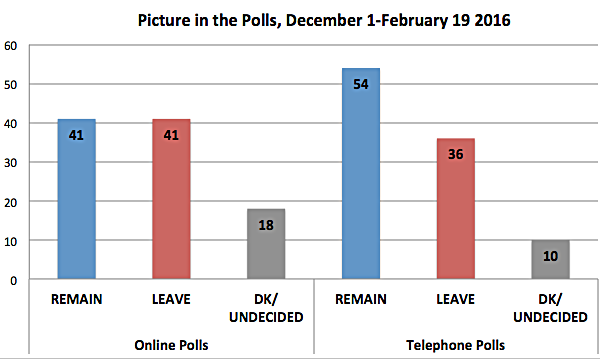

For this bulletin, I ran the numbers on all polls conducted since the start of December 2015. Look at the chart below. In online polls, by companies like ICM or YouGov, the referendum race looks very close. It is a dead heat. Remain is on 41%, Leave is on 41% and undecided voters represent a not insignificant 18%. If you look only at these numbers then you would conclude that there is everything to play for.

But now look at the average result from polls conducted over the telephone. In these polls, conducted by firms like Ipsos-MORI and ComRes, it is a very different story. Remain, on 56%, holds a striking 18 point lead. It looks set for a comfortable victory (this was also true in a new and post-EU deal Survation telephone poll that was released last night that put Remain on 48%, Leave on 33% and Undecided on 19%). It is not even close. In the telephone polls there are also a much smaller number of undecided voters, a point I will come back to.

This is not just a nerdy point. It really matters. The polls will strongly influence the referendum – the campaign, voters and journalists. Just look back to that YouGov poll a few weeks ago that gave Leave a 9-point lead. Brexit loomed. Cameron was toast. But only a few days later along came a telephone poll that gave Remain a 8-point lead, then another that gave Remain an 18-point lead, and then the one last night that put Remain 15 points ahead.

So what is going on?

There are different theories. One possibility is that the polls are being influenced by something called ‘social desirability bias’ – which leads some voters to give pollsters an answer that they think is socially desirable (even if this is not their actual view!) People might not have a problem admitting their desire for Brexit online, but they might be more hesitant when there is another person on the end of the telephone. This might be contributing to the strong lead for Remain in the telephone polls and the fact that these polls report a lower number of undecided voters. Who wants to admit that they don’t have a view?

There is evidence to support this. One study in North America, for example, found that telephone respondents are often more suspicious about interviews and, crucially, more likely to present themselves in socially desirable ways. Another experiment that compared telephone and internet methods found that phone surveys generated more random error and higher rates of social desirability bias. If this is true then it might be that Remain’s strong lead in telephone polls might not be as strong as we are led to believe, or it might not exist at all – although I find that one harder to believe.

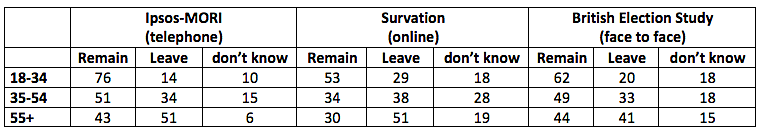

To illustrate these differences, take a look at the table below where I compare results from the most recent telephone poll (Ipsos-MORI) with a recent online poll (Survation). You can see immediately how support for Remain is much higher across the board in the telephone poll whereas in the online poll by Survation there are larger numbers of undecided voters. I’ve also included results from the face-to-face British Election Study, conducted last year. In face-to-face Remain is comfortably ahead but across all three methods you can see how notable the differences are. This is why jumping on single snapshot polls is a game for fools.

Another very real possibility is that the polls are still not adequately representing the views of key groups in society, which could make all the difference at the EU referendum. It has already been noted how, at the 2015 general election, the samples of people in the polls were not as representative as they should have been, over-representing younger Labour voters and under-representing Conservative voters. If this problem has not been properly fixed then it could carry real implications for the referendum. Those Labour-leaning voters tend to be more positive about the EU, which might be artificially inflating support for Remain.

Another specific question is whether the polls are also accurately reflecting the average over-55 year old and young person. These two groups are at the opposite ends of the debate – the over-55s are the most likely to back Leave, while the 18-34 year olds are the most likely to back Remain. But older Britons are very difficult to reach and it might be that current polls are skewed toward more politically engaged older voters. As one pollster, Adam Drummond, recently reflected: “It is possible that the same thing as happened in the general election with young people is happening again with online polls over-representing the easiest over-65s to reach on panels who happen to be more pro-Brexit than the rest of their age group”.

If this is the case, with online samples over-representing more Brexit-minded older Britons, then alongside the evidence in telephone polls it could suggest that Remain has an edge. On June 23 the less engaged older voters who are perhaps less Eurosceptic will turn out and have their views heard. Alternatively, if the samples of older voters are accurate but more ‘normal’ younger respondents are not adequately captured then the race could be much closer than we currently think.

The solution? Well, one pollster thinks that ‘the true answer’ may lie somewhere between what the telephone and online polls are reporting. This school of thought has been influenced by the experience of Ukip, whose vote share at the 2015 general election basically fell between what the online and telephone polls were projecting. But I don’t find that explanation satisfactory – especially given the importance of the national debate and the fact that Euroscepticism is a more multi-dimensional phenomenon than support for a hard Eurosceptic party. What is clear – and is the central message of this briefing – is that until the problem is resolved we need to inject a new sense of caution into how we report the polls.

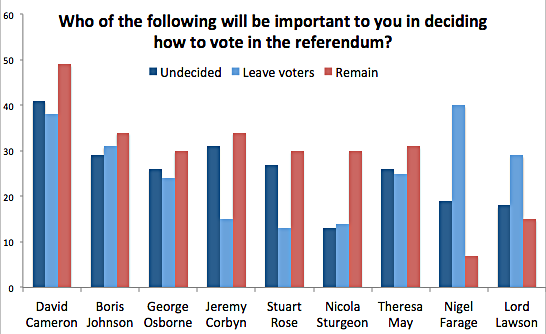

Oh, and one last thing: how important could Boris be? Take a look at the chart below, taken from a very recent Ipsos-MORI poll, and compare the reach of Boris to the only other Outers….

Forthcoming events

On February 24th Professor John Curtice and Matthew Goodwin will be discussing public attitudes toward the referendum at Portcullis House, House of Commons. Register here.

On February 26th Chatham House will also be hosting a breakfast briefing for journalists on the referendum, featuring Anthony Wells and Professor Sara Hobolt. Journalists can register here.

Other evidence-based blogs

Damian Chalmers asks – Ever Closer Union – Does it matter?

John Curtice writes a memo for David Cameron

Chatham House briefing paper – What drives Euroscepticism?

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor of the LSE.

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent, and Associate Fellow at Chatham House. He is also a senior fellow at the UK in a Changing Europe project. His most recent book is the co-authored Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain (2014). @GoodwinMJ

Interesting article; but entirely overlooks the fact that UK Euroscepticism has been hugely influenced over forty years by a largely Eurosceptic print media that is without equivalent elsewhere in the EU. A print media which is today largely owned by visceral anti-Europeans Rupert Murdoch (the Times and the Sun), the Barclay Brothers (Daily Telegraph), Richard Desmond (Express) and Lord Rothermere (Mail). In a country with one of the highest daily newspaper readership in Europe, the influence of these newspapers in formatting eurosceptic opinion is without parallel elsewhere in Europe. To explain the rise and level of Euroscepticism in the UK, look no further than the newsstand.

“Who wants to admit that they don’t have a view?” A good question, but then why should someone who doesn’t have a view bother to respond to an online poll?

I have a wide group of friends and acquaintances from many different backgrounds and about 90% are going to vote leave, with the rest broadly thinking we should never have joined but it is too late to leave now. I just think the result will be a massive shock to a lot of people in the media and only to the public because of the polls. I could be wrong and my friends are possibly not representative of the public though.