The LSE’s Nicholas Barr explains why he will be voting to Remain in the EU referendum – citing a wide range of arguments about sovereignty, migration, international influence, regulation, democracy, trade and the single market to make his case. He concludes the economic and foreign policy costs of leaving are large, and the gains in sovereignty in today’s connected world are limited.

The LSE’s Nicholas Barr explains why he will be voting to Remain in the EU referendum – citing a wide range of arguments about sovereignty, migration, international influence, regulation, democracy, trade and the single market to make his case. He concludes the economic and foreign policy costs of leaving are large, and the gains in sovereignty in today’s connected world are limited.

This article, written for many friends who have asked for a reasoned view of why I will vote Remain, summarises a longer article which sets out the supporting arguments more fully. I include links to evidence from credible sources, none (with the essential exception of the Financial Times) behind a paywall.

Before setting out, some caveats.

- We can’t predict the future with certainty. The world faces major uncertainties – economic (another economic crisis?), political (instability in the Middle East), environmental (climate change), societal (population ageing) and technical (nuclear safety). Thus this note does not claim to be ‘right’, but rather to set out arguments based on respectable theory and evidence.

- The EU hasn’t got it all right – far from it. But that on its own is not an argument for leaving. As William Hague (Telegraph, 22 December 2015) puts it,

‘I haven’t changed my view on the EU: I have often denounced how it works but never advocated withdrawal from it. This is one of many situations in life where finding many faults with something is different from thinking it best to leave it.’

Background facts

UK opt-outs. The UK has a series of important opt-outs: from ‘ever closer union’; from the Euro; from the border-free Schengen Agreement; and from policies on asylum, migration, justice and internal security.

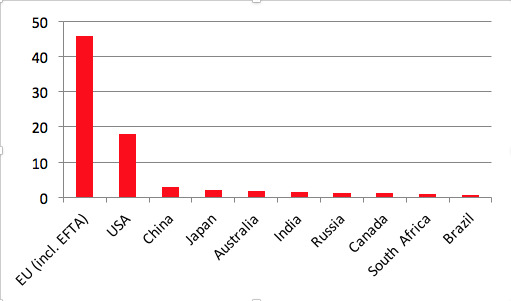

Trade. Figure 1 shows that British trade with the EU is much larger than with anyone else. Trade with China is growing more rapidly but is still very small (2.9%). In round numbers, about 45% of UK trade is with the EU, 18% with the USA and 7.3% with the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa).

Trade matters greatly. There is near-universal agreement among economists that trade contributes to higher living standards, and that reducing restrictions on trade generally increases the gains.

The Single European Market. Free-trade agreements are mostly about goods (cars, chemicals) rather than services (insurance). The Single European Market is about both and therefore has harmonised regulations to avoid non-tariff barriers (e.g. different or incompatible regulations designed to make it hard to break into a domestic market). If the UK is not in the single market, trade in services will be damaged. That matters because only 10% of UK output is in manufacturing.

Members of the European Economic Area like Norway have access to the single market without being members of the EU. However, as a former foreign minister of Norway explains, Norway must (a) accept free migration of EU citizens, (b) contribute to the EU budget, and (c) comply with all EU rules but with no say in making those rules.

Figure 1: Percentage of UK exports to other countries, 2014

Source: UK Pink Book 2015, Table 9.1.

Economic effects of leaving

A short Financial Times video gives an excellent summary.

There is little dispute that leaving would create short-term losses. A Treasury report (BBC 23 May 2016) on the short-run effects suggests a recession, a view confirmed by the respected independent Institute for Fiscal Studies who point to the resulting increase in the budget deficit and argue that ‘It is unlikely that government would respond with bigger spending cuts and tax rises in the short run. More likely “austerity” would be extended by another year (optimistic scenario) or another two years.’

There is also widespread agreement among economists that leaving would reduce economic growth over a longer time horizon, and that the loss could be large.

How large a loss depends critically on which trade regime is in place after we leave. The Treasury’s medium-term assessment models three options: ‘Norway’(remain in the single market); ‘Canada’ (a bilateral agreement with the EU); or based on World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules without any specific agreement with the EU.

‘Britain would face an invidious choice …. The EU would insist that in return for full access to the single market, the UK must continue to sign up to EU laws, pay budget contributions and accept the free movement of people. As Britain would have voted to escape these perceived burdens, higher barriers to trade with the EU are all but certain. The higher the barriers, the greater the damage to the British economy’ (Centre for European Reform, 21 April 2016).

The losses will not fall evenly, but on particular regions (e.g. Cornwall), particular sectors (farming), on particular parts of the country (e.g. where foreign-owned car plants are sited), and on tax-financed public services such as the NHS if lower growth adds to fiscal pressures.

The argument that the UK will be able to negotiate good trade deals quickly is implausible.

- The EU is more important to the UK than vice versa, so our bargaining power is limited.

- Brexit risks a chain reaction, given rising nationalism across the EU (on which more below). Thus the EU’s rational response is to make a horrible example of the UK.

- For non-EU countries (e.g. USA, China), negotiating with the EU offers access to a market of 500 million. The UK is much less of a magnet.

Thus,

‘The claim that the outcome will be fine because Britain is the fifth-largest economy in the world is technically wrong, a non sequitur and a fundamental misreading of history. It is hard to think of a worse argument’ (Chris Giles, Economics Editor, Financial Times, 4 May 2016).

Do we really send £350 million per week to Brussels?

The claim that membership costs £350 million per week, i.e. £18bn per year, is plain wrong.

‘First, the rebate [negotiated by Margaret Thatcher] on Britain’s contributions means the annual contribution is expected to be £13bn in 2015. Of that money, another £4.5bn comes back to the UK as farming subsidies and regional development funds. Another £1.4bn comes back in grants to the private sector. These adjustments reduce the £350m a week to £136m (Financial Times, 1 April 2016).

‘Claims that we would have an additional £350 million a week to spend are wrong. They imply that following a UK exit other EU countries would continue to pay a rebate to the UK on contributions it was not making. Such claims also imply we would simply stop all existing EU subsidies to farming and poorer regions (such as Cornwall and west Wales)’ (Institute for Fiscal Studies 25 May 2016).

In everyday terms, the cost of EU membership is less than 30p per person per day, roughly the cost of a cheap mobile phone contract. The reduction in the government’s tax revenues from even a small reduction in growth rates after leaving would dwarf any saving in our net EU contribution.

Potential international effects

For a summary, see William Hague’s articles in The Telegraph, 22 December 2015, 18 April and 9 May 2016).

Someone misspoke on the radio, asking ‘Will you vote to stay in the UK?’ – but was right. A vote to leave risks destabilising the UK through the possibility of a second Scottish referendum. There are also ramifications for the Irish peace process (Financial Times, 28 April 2016), which depends crucially on both UK and Irish Republic being members of the EU, with no border for people, goods or services.

Leaving also risks destabilising the EU economically and politically. Marine Le Pen is already calling for a Frexit referendum, with a risk that populist parties in other countries, including Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark, could follow (Financial Times, 26 February 2016).

If the UK and EU are weaker, the US is weaker. These pressures enact what has been Soviet or Russian foreign policy for sixty years – divide Western Europe and destabilise and weaken the EU – see the powerful article by Garry Kasparov, Guardian 13 May 2016.

Kevin Featherstone summarises some of the findings of the LSE Commission on Britain’s Future in Europe.

‘A “no” vote … will greatly extend the crises that the EU is already trying to manage. Geopolitically, a Brexit will weaken Europe’s ability to stand up to Putin’s aggression and the challenges of jihadism. The EU would lose a member that has one of its biggest military and diplomatic capacities, its main advocate of interventionism, and the strongest link with Washington. Brexit will threaten the global role of both the UK and the EU. Internally, a Brexit will rejuvenate fears of Germany hegemony, with France alone unable to be the counter-balance, with concerns revived in Europe’s east and south.’

Sovereignty

For some, the economic and international costs of leaving might be a price worth paying if it restored UK sovereignty.

Economic sovereignty. The Westminster government has less sovereignty than in the past. First, globalisation has reduced the independence of all countries. For example, the internet makes national boundaries more porous (music downloads, Netflix), making competition global and reducing the freedom of any country to have taxes and regulations too different from competing countries. That said, the UK retains significant sovereignty over fiscal policy (taxes and government spending) because of the opt-out from the Euro.

In addition, the UK shares sovereignty with the UN, NATO, the World Trade Organisation, etc. (the UK has signed 14,000 treaties (Financial Times, 3 May 2016)); and within the UK, central government has devolved significant powers to regions and cities.

International reach. Though there is room for disagreement about how strong the effect would be, it hard to see how the UK becomes a more powerful global actor by separating itself from its own continent.

Migration. For many, this issue is the crux. The question is not whether the issue is real (it is) but the choice of policies to address it.

In 2015, ‘Net migration of EU citizens was estimated to be 184,000 (compared with 174,000 in YE December 2014; change not statistically significant). Non-EU net migration was 188,000 a similar level compared with the previous year (194,000)’ (Office for National Statistics 26 May 2016).

Historically there have been great benefits from waves of immigration, from the Huguenots to today’s NHS workers. The best available evidence shows that current immigrants are net fiscal contributors and ‘[t]he contributions of those who stay in Britain may well increase. It is a new form of foreign direct investment’ (Economist, 8 November 2014).

Research by LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (see Independent, 12 May 2016) finds that immigration from the EU does not harm wages, jobs or public services. The view that there is a fixed number of jobs, and hence that immigration reduces the number of jobs for Brits, is widely believed but mistaken (what economists call the ‘lump of labour’ fallacy). Immigrants to the UK add to domestic demand for goods and services which helps to generate employment.

Those findings, however, do not rule out local problems if numbers increase rapidly. The case for targeted action is strong; it does not follow that leaving the EU is a good answer.

Even if the UK were outside the EU, reducing immigration would not be easy.

‘Migrationwatch has estimated that applying the current non-EU migration rules to EU nationals would reduce the current 323,000 net migration total by about 100,000’ (National Institute Economic Review, May 2016, p. 20, quoted in the Guardian, 10 May 2016).

Finally, the flip side of ‘gaining control of our borders’ is reducing the right of younger Brits to live and work in other EU countries and of older Brits to retire there.

‘A lot would depend on the kind of deal the UK agreed with the EU after exit…. If the government opted to impose work permit restrictions, as UKIP wants, then other countries could reciprocate, meaning Britons would have to apply for visas to work’ (BBC, 12 May 2016).

Security. The argument that free movement allows criminals to enter the UK should not be overstated. Driving from Brussels to Amsterdam, the only evidence of a border is the sign ‘Nederland’, like ‘Welcome to Somerset’. Such borders offer no security against terrorists or criminals. But the UK has an opt-out on the border-free Schengen agreement and thus has passport control at its borders. Failures of security are largely domestic, including self-inflicted cuts to Border Agency staff.

Democracy. The argument about ‘unelected bureaucrats’ is spurious. We never get to vote for Treasury or Home Office officials. The real questions are:

- Is there a democratic deficit in the EU, i.e. does the European Parliament exert sufficiently powerful democratic oversight over the activities of EU officials? There are legitimate doubts whether that is so.

- How likely is it that the problem will be addressed? There are grounds for optimism: the problem is recognised and other member states share UK concerns, so that pressure for change will comes from multiple sources.

- Is this issue a reason for leaving? Clearly views can differ. Mine is the same as William Hague’s in the quote at the start of this article.

For what it is worth, there are 55,000 EU civil servants; the UK has 393,000 (BBC, 13 May 2016) .

Regulation. It is argued that the EU imposes heavy and unhelpful regulation.

- OECD studies show that the UK has the second least-regulated product markets among industrial countries and the least-regulated labour markets in the EU.

- Regulation has benefits. Co-ordination (for example, common safety standards for electrical products) is a necessary part of a single market, making it easier to trade. It also provides consumer protection, e.g. cheaper air fares, lower roaming charges, cleaner beaches.

- What many regard as the most burdensome regulations – planning – are self-inflicted.

Leaving the EU would not reduce regulation substantially. The issue is not regulation as a whole, but removing or revising the bad regulations that undoubtedly exist. That is a highly worthwhile task, but not a reason for leaving.

In sum. The UK remains a sovereign country in the sense that we can at any time decide to leave the EU. However, we cannot as easily decide to rejoin. The opt-outs described earlier were negotiated when the UK was a member state, hence with veto power. Were the UK to leave and later to reapply, the opt outs would no longer be on offer.

Benefits of EU membership

The argument is not only about the costs of leaving but also about the benefits of membership.

- Peace should not be underestimated because so few people are left who can remember the Second World War. The EU has also helped to consolidate democracy in Southern European countries formerly under military dictatorships and in former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Membership of the world’s largest economy creates considerable economic benefits.

- Membership gives greater control of the international environment (climate change, control of multinationals, action on tax havens).

- Free movement benefits the large numbers of Brits who live and work in other EU countries, something of particular relevance to younger people who live and work in other EU countries for part of their career and older people who retire to warmer climes.

Conclusion

For different mixes of these reasons,

‘Best friends from Washington to Wellington, Ottawa to Canberra and Tokyo to Delhi are unanimous that their relationships are tied to Britain’s place in Europe. Nato, the ultimate guarantor of British security, thinks the country would be disarming itself by quitting’ (Financial Times, 19 May 2016).

Comparing costs and benefits is not as exciting as a rousing political speech, but is the right way to approach a hugely important decision. For me the balance of arguments is clear: the economic and foreign policy costs of leaving are large, and on my reading the gains in sovereignty in today’s connected world are limited. The issue is not about the older generation’s past but about our children’s and grandchildren’s future. For those reasons, I shall vote Remain.

A minimal reading list

On factual matters, see the BBC reality check, www.bbc.co.uk/realitycheck

On economics, see the short video by Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times.

On international aspects, see the articles by William Hague in The Telegraph, 22 December 2015, 18 April and 9 May 2016

On sovereignty, see Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 3 May 2016.

LSE Commission on Britain’s Future in Europe

LSE Centre for Economic Performance

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Alok Basu, Iain Begg, Richard Bronk, Anne Corbett, Richard Goeltz, Abby Innes, Waltraud Schelkle, Ros Taylor and John Van Reenen for helpful comments on the longer version of this article. Remaining errors and the views expressed are my responsibility.

Also by Nicholas Barr: EU membership is not the only way to foster labour mobility. But it is the best

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.

Nicholas Barr is Professor of Public Economics at the European Institute, London School of Economics. N.Barr@lse.ac.uk

A deluge of pro EU data descends on us.

However, no one looks at what happens after a remain result.

The Euro-zone will come together as the United States of Europe because it must or its Frankenstein currency will implode.

Then what?

Britain is to be the Puerto Rico of the United States of Europe? Is that it?

We WILL be dictated to. Make no mistake.

The track record of “experts” at prediction is alarmingly bad – throughout history.These studies are notorious for finding a result & then posing a question.

The smart move is always to keep your powder dry – but the remain camp want to dream that the French & Germans & Dutch have our best interests at heart. They do not.

It was German & Dutch politicians that came over to Britain before we joined the EEC to assure us that they were really on our side & they would ally with us against the French to stop “ever closer union”. But once we joined they did nothing. They lied then & they lie now.

It’s frustrating to read a balanced and well presented argument with none of the usual rhetoric or fear mongering about the referendum only for the first comment to be full of unsubstantiated rhetoric and fear mongering about the referendum. Nothing you have written can be backed up. And before you start, I’m personally still undecided.

Tom:

Yes we can all of us put together a well reasoned position paper for the EU, but what about the important questions? Where are they?

You ask for back up.

OK.

Do you accept that there is something fundamentally wrong with the Euro currency?

If you do then what would you have done about it to put it right?

At this point you should have a queezy feeling in your stomach.

That is the back up!

So to be clear: get out of Europe if you have a spot of dyspepsia? Do we invade Poland if we have a mild migraine? How about we jettison London if we have a really bad case of food poisoning?

Your kind of comment makes the Brexit campaign look pretty bad. No discussion of points but remarks about gurgling stomachs.

PS You forgot to end your posting with CAPITALS!

Adam:

Were we all to descend into sarcasm as you do then an already confused argument will go further downhill to chaos.

Tough questions need to be asked & if possible, answered. Produducing neat summations of economics [for example] goes only so far. These same economists told us that unless we joined the euro-currency we would become a “has been” economy. There were 2,000 economists & World “experts” during 1999 just before the euro currency launch telling us to join that club.

The big question is all about that currency & what is to happen to it.

Answer that question then be as sarcastic as you please.

I look forward to your contribution Adam.

Interesting, Mr. Wainwright.

However, you perhaps need a little education! The UK has never invaded Poland and indeed that was the trigger that started WW2 when the bully boy of Europe, Germany, invaded Poland in 1939. It was the UK and France that joined forces to come to the aid of Poland. End of History lesson!

Your asinine comment about London beggars belief! By chance, do you happen to know what a “non sequitur” means? If not, please research it!

Perhaps you can help my education. I am unaware of any requirement to end a post with capital letters in the English language. Please could you direct me to your authority? End of English Language lesson.

Your fixation with biology is interesting, but it does have a rather narrow focus. When you wrote your post, did you have a bad case of Montezuma’s revenge? If so, perhaps not the best time to try to write an academic reply! End of science lesson.

Please do not criticise others for “No discussion of points …” when you do not make a single point on the debate itself. End of lesson on hypocrisy.

Before you think about it, I am well aware of sarcasm and how it is used. However, are you aware of Wilde’s definition of sarcasm, namely “the lowest form of wit”? I am aware of Wilde’s continuation, but do not believe he was right all the time and that is exemplified in your post!

Seriously, perhaps it may help If you think carefully about all the issues. In particular, look at the promises made by our PM before his meeting with European leaders and then examine what he achieved. The key issue is not economics, but sovereignty! Did he achieve anything on this issue? In my opinion, if we do not leave the EU, the peoples of the UK will become little more than serfs to our masters in Europe. Look how the EU tries to bully us and how the so-called “independent” BBC behaves in presenting the arguments nearly always from Cameron’s point of view. If you want to live in a control freak state perhaps North Korea might oblige.

“The key issue is not economics, but sovereignty! Did he achieve anything on this issue? In my opinion, if we do not leave the EU, the peoples of the UK will become little more than serfs to our masters in Europe.”

And who exactly are our “masters in Europe” – the French? The Germans? The Italians? The Dutch? Saying we will lose our sovereignty is tantamount to saying that Cornishmen are indistinguishable from Yorkshiremen, despite both being part of Europe’s oldest federal super state since the time of King Alfred. Or Queen Anne, if you care to include the Scots. ‘Sovereignty’ is one of those emotive buzzwords that gets bandied about an awful lot but doesn’t really mean much to any one particular individual living in an island that has been continuously settled – sometimes peaceably, occasionally not – since the time of the Beaker people. I have to class myself as “white British” on forms, but that includes Scottish, Welsh, Irish, Dutch, and Huguenot (going back about 5 generations) in addition to English. For every one of your “sovereignties” I’ll see you and raise you a mongrel Brit.

TiddK your reply is interesting, but is little more than a feeble attempt to divert attention from the key issue, that of sovereignty, to a would be history lesson! Incidentally, it is poor English to start a sentence with a conjunction. In your case, the word “And”!

To start, the way in which I used “sovereignty” is the standard usage. To wit: the right of a country to make its own laws and to rule itself. Sovereignty is NOT “an emotive buzz word” for it has a precise meaning and usage. The Shorter English Dictionary defines sovereignty as follows:

1. Supremacy in respect of excellence or efficacy; pre-eminence.

2. Supremacy in respect of power or rank; supreme authority.

3. The position, rank, or power of a supreme ruler or monarch; royal dominion. b. The supreme power in a community not under monarchical government; absolute and independent authority of a state, community, etc.

4. A territory under the rule of a sovereign or existing as an independent state.

Interestingly, the next entry in that dictionary is “Soviet”! Perhaps appropriate as Marxists hardly ever tell the truth and attempt to disguise their lies and/or dissimulation.

Your attempt at dissimulation is to try to argue that sovereignty is something to do with your feeble attempt at a history lesson. As usual for the Remain campaign, completely removed from reality and attempting to mask the truth by any means that come to their (increasingly desperate) hands!

To answer your question about “our masters in Europe”, I find it interesting that you list 3 countries, namely, France, Germany and Holland. All three of the countries have been at war with Great Britain at various times. If you don’t know or understand to whom I was referring by “our masters” then perhaps you have been having too many late nights playing poker and ignoring what is happening in the world! I refer, of course, to the unelected rulers of the EU.

In your attempt at dissimulation, you list your bloodline and your ancestor’s nationality. In my opinion, you ought to go down on your knees and thank Great Britain for giving sanctuary to your Huguenot antecedents! Had Great Britain not done so, you would not be alive today! Ever heard of the word, “GRATITUDE”?

In conclusion, I should love to play poker with you! It has been ages since the poker school to which I belonged ended and the money would come in handy to help launch a legal challenge against the Government for illegal use of taxpayers’ money and the BBC for blatant bias in its news coverage.

Raise, call or stack?

First, I will take no lesson in English grammar from you : starting a sentence with a conjunction is perfectly acceptable (a stylistic device) and I fear you have unconsciously taken on board the so-called “rules of English” promulgated by a certain 18th Century clergyman which were actually based more on Latin than on our unique blend of Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Norman French.

Second, it is obvious that I was not giving a history lesson. I was simply pointing out that England (and only later , the UK) is one of the oldest federal unions in Europe, and we therefore have nothing to fear from (an imagined) European superstate. One day it might happen, but even so we would not lose our unique Britishness which – as I said – is comprised of many races and ethnicities over millennia.

You say that our “EU masters” are “the unelected rulers of the EU”. There ARE no such thing. There are only unelected bureaucrats in Brussels, akin to our unelected Civil Service in Whitehall. There IS a European Parliament to which all MEPs are elected. And each nation is ruled by its own government, in our case by a parliamentary democracy loosely underpinned by a monarchical head of state; the French have a Republic as do the Germans; the Dutch have a similar system to ours, as does Spain, and so on. And (note that conjunction again – I choose it carefully) we have an independent judiciary that administers a blend of Common Law and statute; any decision can now of course also be referred to the European Courts, but only in certain circumstances. But (another conjunction) I do accept that the EU makes laws about things like workers’ rights, which we must accept – and thank God, we do! – while being in the EU.

I am well aware that the nations I chose have been at war with us at one time or another. That is precisely why I chose them. Well done you, for spotting that. It is because of the original Treaty of Rome that Europe has enjoyed a period of peace since WW2, at least between the countries that make it up.

I am now very tired having penned this long reply and I am to bed. You will have to start your all-night poker game without me.

TiddK,

Thank you for your reply.

It is a great pity that you do not wish any help with your use of English from me. Before I retired, I taught English at A level to a variety of students in state schools with considerable success. My credentials: I hold a degree from the Institute of Education, University of London. At Birkbeck College, University of London (part time whilst working) I achieved a very high two/one in compulsory Anglo-Saxon and a very high first in my thesis on Mathew Arnold assessed by Professor M. Allot, one of the two foremost world experts on Arnold at that time. So I feel I am fairly well qualified to assess the use of English.

You are right that it is possible to open a sentence with a conjunction, but rarely and used with considerable care. In your last missive, you used one unattributed sentence starting with a conjunction and two attributed ones. Three in about two hundred and twenty words. Rather overkill methinks! Further to your use of English: “First, I will take no lesson in English grammar from you” and “… there are no such thing.” Both use the negative and that may imply that some instances are extant! Not good style, I’m afraid. Sadly, there are some less than attractive split infinitives in your document! In addition, “…there are no such thing.” Is a mix of singular and plural. I will assume that “The nations I choose … (sic) could be a typo, but perhaps more elegantly phrased as “the nations I have chosen …”. Chose is the correct form!

I do not make any apology for the English lesson, but my original comment about conjunctions was somewhat lighthearted. Perhaps a little work needed on sense of humour?

I assume that the 18th century clergyman to whom you refer is Robert Lowth and his book, “A short introduction to English grammar (1762)? Sadly not, I’m afraid, but I was fortunate to have an outstanding Teacher of English, Mr. Hugh Kelly, now sadly departed.

You claim you were not giving a history lesson, but as your post contained slightly more than 20% of history, It seems fair comment. In any event, another whimsical remark intended to lighten the mood. Perhaps a little more work on the sense of humour?

I notice you do not address the substantive issue, that of who rules the UK, its people or bureaucrats in Brussels? At the moment it is Brussels and we have very little say in decisions about our lives and how our country is run. Perhaps the reason that many citizens of the EU are rejecting the idea of the central government is that citizens feel helpless and disenfranchised! Furthermore, recent behaviour by EU. leaders has not reassured the public, including those in France and Germany. The behaviour of David Cam Moron in his recent trip to Europe, beggars belief! The reason why it looks likely that the Leave campaign are winning is that the Moron needed to attend RADA rather than Oxford. His acting ability is close to zero and I doubt many were fooled by his claims of an Exhausting workload and Successful concessions from the EU!

Your admission that the EU makes laws about “things like workers’ rights” is correct and in many ways helpful as it tries to redress the balance between poor quality employers and employees. If the Leave campaign win, how long do you think the Tory party will keep the Moron and his mouthpiece clown (Osborne)? Why do you think the level of desperation from Downing Street is increasing daily? I notice from your other posts that you dislike IDS and I agree with you. My wife and I are disabled so are well aware of what is going on!

Finally, two points: unfortunately I do have the energy for all night poker. You cannot be all bad for it appears you like Dad’s Army. Don’t panic Mr. Mainwaring (it’s not the glorious 23rd yet!).

Mike Stringer – two things that really aren’t done: (1) correcting one’s interlocutor’s English during a conversation or debate; (2) falling back on a list of one’s academic qualifications.

The rest of your comment is so full of logical fallacies, paranoid fantasy and plain untruths that it’s difficult to know where to start. Really, it’s quite an achievement. Were I to set out and try to write the most absurdly illogical and asinine non-argument for Brexit, I’d struggle to do as well as you. Chapeau!

[I shall skip the English lesson you began with, as well as the insults you decided to employ in your response to me – you demean yourself when you argue like that, not me.]

“I notice you do not address the substantive issue, that of who rules the UK, its people or bureaucrats in Brussels? At the moment it is Brussels…”

You describe the question “who rules the UK” as the substantive issue. Firstly, this is begging the question (an informal fallacy): you’re trying to frame the debate so that it depends on answering a question of your choice, and then immediately answer it without providing any evidence. The reality is that in 21st century democracy, all modern states devolve some of their sovereignty to international organisations. This was explained quite clearly in Nicholas Barr’s article.

There is no factual basis for your claim that the EU “rules the UK”. What is true is that the UK has agreed to EU rules concerning some aspects of governance. But in the most important aspects of sovereignty – control of territory and frontiers, and the ability to exert power or force – the UK has not ceded any power whatsoever to the EU. It has ceded some power to NATO – because of our membership, we are not allowed to raid France’s channel ports or bombard Cadiz – but nor are our fellow member states permitted to do the same to us.

Finally, in a legal, constitutional sense, the Crown is sovereign in the UK. The Crown’s power is based on the Queen herself, and exercised through Parliament.

“Your admission that the EU makes laws about “things like workers’ rights” is correct and in many ways helpful as it tries to redress the balance between poor quality employers and employees.”

I don’t know what this means. His admission was helpful? Or the EU laws are helpful? And what are “poor quality employers and employees”?

Jim

So your whole basis is on the Euro. Something we are not a part of, and won’t be a part of unless we decide (this would have to go to referendum).

That like being scared of a bogeyman hiding in a cupboard.

The author has made many reasoned arguments. Debate them on those.

Dave:

You seem to think that the euro does not affect us because we are not a euro-zone country.

Not so. The euro may well destroy the EU & do so in circumstances that cause real havoc to us.

Also you want to debate on what Nicholas Barr wrote leaving out the elephant in the room. This we must not do.

The euro is the dangerous fault line in Europe & how it is dealt with is crucial.

There are very limited options as you should know.

Consider those options.

I encourage everyone to just think – hard & long about those options because the euro is still on a roller coaster ride & is still not under control & can never be under control without a united government of Europe [a United States of Europe] which we will be outside of but which we must accept as the big boy on the block..

Please think. I encourage everyone to think.

Jim, there is indeed a lot wrong with the Euro, the lack of political union precludes any sort of fiscal union and therefore the economic tools to deal with the severe crisis the Euro is currently facing. Issues of sovereignty make any potential future political and fiscal union between EU member states very unlikely in the forseeable future. However, the goal of “ever closer union” is nothing new and its function to create political and fiscal union and therefore empower the ECB to tackle such economic crises more effectively. This said a few points for you:

1. The UK doesnt use the Euro does it? Nor does it ever look likely to do so?

2. Even if the Euro failed and all member states reverted to sovereign currencies would that automatically mean a failure of what was the EEC and the basis of what is now the EU?

3. “Ever closer union” is nothing new, if you do your research you will realise that this was the idea in the 1970s. Sectors of the British public are only just waking up to this 40 years later. De Gaulle vetoed UK entry due to a deep seated hostility toward the European initiative. If your comment represents the majority of Britain it serves only to prove that De Gaulle was correct to twice veto entry of the UK.

4. If the British public decided to remain a member of the EU, how would this stop implementation of article 50 of the Lisbon treaty at a later date? Before you say that the EU would plug that hole with a new treaty, that would require the consensus of all EU member states before it could be ratified.

Nicholas:

Of course ever closer union is not new. We all knew this on entry to the EEC. That was when many German & Dutch politicians appeared on our TV screens nightly telling us that you can`t change the [then] EEC from the outside but come on in & we will support you to change ever closer union & the CAP et al.

It didn`t happen because once we joined they forgot about their promises.

As for article 50, forget it. It is the Euro zone that will decide matters as Cameron found out when he was out manouvred by the EU taking their decisons within the Euro zone not the EU per se.

We must all be careful not to indulge ourselves in a leap of faith.

Buit, at least you are thinking. Good. Keep it up.

Well said, Jim. Your comments and responses to those that are challenging them are cogent and we’ll thought out. Nothing in this article convinces me to vote ‘Remain’.

These economist types are almost consistently wrong.. about everything. Didn’t hear any of these geniuses predicting the 08 crisis for example. Do yourselves a favour and watch this – https://youtu.be/UTMxfAkxfQ0 (brexit the movie)

Remain – I finally get it, it is about the economy and jobs. If we want those we must listen to the experts from financial institutions, investment bankers and hedge fund managers, they will give us jobs, if we only surrender some of our liberties, if we don’t they will punish us, I get that. It is scary.

But before we give them democracy just think of this first … Many countries of Europe flirted with fascism in the 1940s, (even Vichy sad to say), extremism was on the rise. In Great Britain, we gave the fascists a voice but they gained no traction, mainly richly deserved ridicule – that was because we had fully functioning parliamentary democracy, everybody had a voice. Our parents and grandparents knew how valuable that was so, they downed tools and risked all, to fight for it. I am eternally grateful to that generation. By their example, they brought peace to Europe and for the longest period in its history (with a little help from the US and commonwealth soldiers in Nato), I know that others claim all the credit. By doing that their generation also showed what free and democratic people can do in the face of dictatorial government oppresing its own people and conducting unspeakable terror., power has always corrupted, always.

So, do as the money people say, back in the fold with us, they can keep the control. We will be just fine, we can’t all end up like Greece – 40 years of austerity to pay off EU enforced to banlks to pay for work undertaken by their corporate confidants.So our european cousins in Greece have 55% youth unemployment – but they can come and get unskilled and lower paid work in the North of Europe – which will admitedly lead to a reduction in wages – that is good for profit.

The EU trajectory has been higher debt, lower employment, more extremism and more state control of security – I don’t want that future, I want what we had,

This article is yet more personal opinion masquerading as balanced scientific analysis. Why do universities no longer teach students to be sceptical? When I was a student in the early 1970s, we were anti-establishment and pro working classes. Today, it is quite the opposite.

What’s even worse are rather odd individuals who claim they are undecided in order to make their eventual (inevitable) remain stance sound substantiated. Lying is typically consistent with both sides it seems.

Everything I said was based on logic and analysis and will become self evident, all backed up by Mervin King Ex-Governor of the Bank of England. The Italian banks are collapsing, economies of Greece, Portugal and Spain being ruined. The eurozone is now in serious trouble and cultures, countries being destroyed by free movement, and the terrorist threats never greater. In a few years people will realise Brexit was the best decision we ever made.

This is your conjecture, but you offer not evidence for what you claim about the Euro or otherwise. Besides which, not all EU countries are part of the Euro, notably Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary. There are others! Also the EU will not disintegrate, as too many of the Eastern European countries have a large vested interest in belonging to something which allies them to Western Europe, for security as well as other matters.

On the other hand this blog is extremely well argued and makes many sensible points, but is not wildly partisan.

You lost any sympathy to your argument when I read the stupid phase “Frankenstein currency” . The more I read, Brexit have to use repulsive terms like “enslaved by europe” as in UKIP literature, “we want out country bank” is another banded about freely and ignorantly. Why are you so insecure in your nationalism, Germany isnt or France? Im British European simple. We need to stay in to reform the market 45% of our trade is with and is what makes us the 5th largest economy because of it. Norway pay £135 per household to trade with EU from Outside and accepts its rules, we pay £87 per household. Immigration in UK DOES have a points system already while to keep quoting Australia, their system is not to curb immigration but select who it wants, creaming skills off other nations. A while Im at it, Gibraltar…. what happens when we are ‘outside’ and Spain wants to close a boarder on mainland europe as it will be a prime target for refugees……?

Richard:

Well I am sorry indeed to have lost your simpathy & even more sorry that you lost your manners.

The Frankenstein currency is exactly that. A cobbled together elitist idea based on the old 1854 LMU single currency which also failed & from which France & the others did not learn anything.

The fault line is there if you look for it.

Think!!

Infants in a BIG wide world.

Jim,

Why do you assume that the French, the Belgians, the Dutch won’t have ‘our’ best interests at heart but fellow Brits in charge of our own country after Brexit will ?

It all really depends on who you are referring to when you use the word ‘us’.

For me ‘us’ doesn’t mean I always give or expect favour from someone else purely and simply because they happen to come from the same country as me.

I prefer to see ‘us’ as any one of the vast number of people across Europe who share the same social values as I do and I would much rather trust them to make the decisions that will have my best interests at heart, than I do the many members of the British ruling classes that make the decisions which effect me in my own country.

Martin:

You are far more trusting in the continental Europeans than I am & I truly wish you well with that trust.

Most contributors here have long since made their minds up as to what their vote will be on the 23rd June.

As for the “British ruling classes” of which you write – well don`t you think that people should stop voting for “Them”? Why don`t you persuade the people not to vote for “Them”.

But that surely is a different issue altogether [it really is].

“The track record of “experts” at prediction is alarmingly bad”.

You said it.

Nicely put!

Tony Blaire made a much broader argument for staying in the EU, that trade is at the heart of our relationship and that if we left we would have to renegotiate trade deals. That being part of the EU is better for our security as there are world-wide wars being fought in Africa, in Phillippines, in Afganistan, and that we are safer staying in the EU. Staying in the EU we will also have a chance to reform the EU.

Sorry if i am incorrect but being in EU does not make us safer as there is NO EU army or deface organisation, that is NATO and has nothing to do with EU, we would still be part of NATO should we choose to leave the EU, being part of the EU many high ranking military actually say makes us weaker and at more risk as we don’t in reality have control of our borders and with the economic migration being what it is today surely that does pose a huge risk to the UK

You’re really going to listen to a man openly lied about reasons for going to war with a country. This is a man who is guilty of unlawfully killing thousands of British people in a war for oil money and is a proven liar and you think listening and acting upon this persons advice is sensible?

If Tony Blair was the leader of a middle eastern country he would be considered a tyrant, and the vote in camp looks to this guy for advice?

Are you being serious right now?

Am I being censored?

So because Tony Blair was wrong about Iraq, he was wrong about everything else? That winning 3 General Elections in a row was simply a trivial chimera? I have the teensiest-weensiest feeling that I would sooner listen to and believe Blair than Nigel Farage, Michael Gove, and Katie Hopkins.

This is an excellent presentation of the reality surrounding Brexit – I couldn’t agree with you more. However, if logic fails we have a powerful partner in Behavioural Economics to fall back on. We can most certainly count on the Default Effect ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Default_effect_(psychology ) to boost ‘Stay’ votes. Between the two, it should be enough to keep us in the EU.

The EU have no agreement regarding services the same as they still do not have an agreement with the USA. If you start your article with lies how can we believe anything.

Not only that, but he says, “Norway must … comply with all EU rules but with no say in making those rules.” This is completely untrue. Norway, sitting as it does, on many international standards bodies (compared with Britain, which can’t due to its membership of the EU), in many respects has more influence over policy than any EU member state. This article also counteracts the views of the Norwegian foreign minister: http://eureferendum.com/blogview.aspx?blogno=84212

As the article says., Norway does not need Brussels to tell it what to do, neither can Norway tell the EU what to do. And with the stagnation of the price of Oil. Norway will have to make sure it holds onto its markets if it wants to remain Not being told what to do…..Norway is also a part of the EEC, I believe the Brexiters want a complete break. Norway also has the toughest immigration laws which are contrary to EU laws. On many occasion Norway has been accused of cherry picking. And they still have to pay to remain part of the EEC something which they definitely cannot afford to lose.

The EU will still exist once we leave; Climate Change will still be tackled, the southern states previously at war will remain at peace. I am majorly pro-EU for many of the benefits mentioned however, the constant assumption that everything will collapse when/if we leave pushed me to look at the argument from the other side.

I’ve now come to the conclusion that, fundamentally, democracy far outweighs economics for me. Imagine if Robert Mugabe decided not to hold Zimbabwe’s next election based on the economic costs involved? There’d be an outcry! Yet here, and all throughout this debate, we are being scared with respect to money; that we might be a tenner a week worse off… There’s a bigger picture here guys and, frankly, I’d happily take a small financial hit in the short term if it means the people we elect into Parliament are the people responsible for making and voting on our laws. That’s what democracy’s about; and I’m sorry, but we shouldn’t put a price on that.

Andy – “That’s what democracy’s about; and I’m sorry, but we shouldn’t put a price on that.”

Beautifully put. For me that’s it in a nutshell!

I’m right there with you Sir. I am still not decided myself but all of this ‘stay or suffer death by a 1000 cuts’ rhetoric has me ill with contempt for leadership that seems to have no consideration for what might simply be ‘right’ despite the costs amd sacrifice. Its cowardly and leads us down a path of perpetual dependence and control because we will always be afraid of what might be if we have to stand alone.

As you have also said, the right to directly influence the political decisions that govern our own country and lives is a right worth fighting and sacrificing for. We are not a small, weak, or incapable nation and forcing ourselves to dig deep now and build a solid (and sovereign) foundation for the future seems to me to be short term sacrifice for long term freedom and independence. Hmmm…maybe I have decided after all.

So much talk about democracy, but what does it really mean? If you live in certain parts of this country, very little! Outlying regions such as Cornwall, Cumbria, and parts of East Anglia are utterly neglected by Westminster politicians because there are not enough votes to merit attention. The EU makes investment decisions on the basis of economic need, because they are not directly dependent on votes. There are huge areas of our lives over which the EU has no influence, and neither do voters. Increasing government interference in education, for example, has damaged both teachers and children with ill-conceived and inappropriate testing, and we have no way of changing that because there are no safeguards. Taking back control is a useful slogan for exploiting popular frustration, but that frustration arises from British government policies, and the EU has little to do with it. If we vote out we will have an extreme right-wing regime in England (the other parts of Britain may be able to escape) and ‘democracy’ will count for very little!

Except what is right for most, especially the most disadvantaged is that the country prospers financially as a whole. The argument is that even if we leave we’ll have to follow many of the laws of the EU to trade in the single market (as Norway does) so being out wont really effect the sovereignty much. It actually explains this in the article.

Well put Andy. That’s what matters most to me too.

Not withstanding the evident intelligence of this excellently written and factually supported letter, the EU system of government nevertheless strikes me as hugely undemocratic and extremely resistant to change. Although it may have substantial benefits, this drawback is all-important to me. Some have suggested it should be changed from within and this, of course, would be preferable but there is no evidence, in my opinion, that the political elite within the EU are prepared to consider change and certainly not radical change as would be needed.

The democratic recourse to remove those with power every 4 or 5 years, if we are not satisfied with their performance, is an absolute pre-requisite in my view. However, if we vote to leave, in particular by a small margin, perhaps that would force those in charge to wake up and realise that we may be serious and that other members may indeed sympathise with our dissatisfaction and start a more genuine negotiation in a serious attempt to preserve the integrity and cohesiveness of the EU.

I have recently started to think that it might have been better, for this increasingly rather ugly campaign, if the referendum had been set up as a two step process. An initial referendum on 23rd June as currently set with a second and final referendum set for two years later if the result is a win for Brexit. i.e. If the Remainers win then we just get on with it but if the leavers win we have a two year period of intense negotiations during which we would try to establish a clear picture of the differences ahead of us. The EU could come to the negotiating table and clarify how much they are willing to change if we choose to stay and put that in writing so that it is unequivocal. Furthermore, they could clarify exactly what deal we would have on offer should we make a final decision to leave. We could also, at the same time, negotiate some other deals with other countries to try and see how they progress.

In the last couple of months we could then have a second and final referendum having removed much of the uncertainty and consequent conjecture that has led to the feeling of scare-mongering on both sides that has bedevilled the campaign we have had. Perhaps then we would have fewer voters being pushed in one direction or the other by “fear of the unknown”.

I wouldn’t mind betting that this is what we will end up with anyway if Brexit wins, in particular by a small margin. The EU is simply likely to say “OK. You mean it so we will negotiate in better faith now and then we expect you to repeat the referendum” which is what they have done in the past when they haven’t liked referendum results, further supporting the accusation that they have no interest in democratic processes!

Andy, Alister, Wayne,

I agree with the importance of democracy but can’t see BREXIT as a viable solution here.

Every political institution is created to solve the political problems at the time of its creation. The modern sovereign nation state which came into existence in the early 18th Century was created to solve the political problems of that time. Over time things change and those political institutions are seen to be no longer valid so change, that change can take some time to happen. As an example we’ve been a democracy for hundreds of years but over that time the number and type of people who can actually vote has changed dramatically.

Then, over the last fifty of so years there have been huge changes to how the world operates and is understood. Commerce is truly global, markets are global, people can move continents (let alone countries) overnight, ideas flow freely in all but the most censorious states and we better understand the global nature of the environment and our impact on it.

Given this the key question is whether the sovereign nation state is the best political institution to solve the global problems of the 21st century? By definition you can’t solve global problems by yourself, you have to work with others and that necessitates the need for shared decision making. Something like the EU gives us a way forward to do this. Yes I agree that there is a lack of democracy in the EU, but the answer to this is to push and make the EU more democratically accountable rather than walk away,

Spot on, Andy! Well said. We need to keep a clear focus on the issue: who makes the laws for our country?

The Remain Campaign will use every dirty trick possible to win. Especially David Cam Moron, who couldn’t lie straight in bed.

The so-called “economic argument” is a feeble attempt to divert attention away from the one and only issue. That is SOVEREIGNTY first, last and always! I’m sure you remember how all this started with the EU dictatorship over-ruling our Supreme Court at every opportunity. They forced the great British people to keep terrorists in our country at our expense and at risk of life and limb. They have wrecked several of our core industries by not allowing our laws to govern us. Finally, they are a bunch of self-satisfied, corrupt bully boys whose comeuppance is not too far distant. If we leave, others are likely to follow.

Thanks for this article and for some interesting comments to which I would add these:

1. For anyone who thinks the EU isn’t democratic, I’d be grateful if you could read my post about how EU law is made. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-eu-institutions-how-does-law-making-work-stephen-dilley?trk=hp-feed-article-title-comment In the light of that, I’d interested to hear specifically what you mean when you say it isn’t democratic.

2. For people concerned about sovereignty such as Mike Stringer, here is an insight into that complex issue: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/legal-sovereignty-same-democratic-accountability-brexit-wakefield?trk=hp-feed-article-title-share . I would add to that by observing that Sovereignty is a relative concept. A Brexit that involved remaining in the Single Market like Norway or Switzerland would cede, not gain, net sovereignty. The UK would be required to comply with EU law that it had not influenced, would have to accept free movement of people and would have lost its powerful veto on both the accession of new states and the EU budget as well as influence over development of the Single Market in services, which is only around 25% developed relative to the Single Market in goods.

3. For those concerned about the price of membership, here is an interesting thought: The U.K. Govt’s debt is around £1.6 trn. That means that every 1 percentage point change in the interest rate for servicing our debt adds or subtracts £16bn pa to/from the national budget. Coincidentally, that figure is not so very far away from the Brexiteers’ £18bn per year gross payment to the EU and well above the net contribution. It seems unlikely that a Brexit scenario would therefore free up extra money (whether for the NHS or anything else). That’s without even counting any money we’d have to pay in if we adopted a Norwegian model.

4. Some posts note that the scale of the European market in the global economy has declined in relative terms. Yes – but far more importantly for the UK, the EU market has grown in absolute financial terms. It would still be the second biggest market in the world without the UK, will remain our largest export market by a significant margin, and is geographically closer than any other market.

5. I agree that in the event of a Brexit, the UK would seek to do some sort of trade deal with the EU. However, for those who say a trade deal could be done relatively quickly or easily:

(a) A new trading agreement with the EU would require the unanimous agreement of all 27 remaining EU member states. It is only Germany and the Netherlands who export more to the UK than they import. That leaves 25 members states that don’t.

(b) The EU sells 6% of its goods to the UK vs us exporting nearly 50%. See Bank of England document: EU membership and the Bank of England, October 2015, page 8. I suspect if I were selling, it would be easier to find a market for 6% of my goods than 50% of my goods, if I really needed to.

(c) The EU FTA with Canada took 5 years and 5 months to negotiate and sign. Ratification is expected to take another 2 years.

I am beginning to wish we had not been offered the referendum at all. If the vote is to leave, we may suffer financially and our security could be damaged. Why on earth would the rest of the world want to give us preferential trade agreements? If the vote is to stay, we may well be walked on even trampled by the push for more unity and more faceless control. Before this offer, we had the lever to effect change by the threat to leave, after the vote to stay, that will be redundant.

Security is best achieved by unity, ‘United we stand, divided we fall’. Do we really want to see Putin become more confident and more aggressive? Will our decision to leave cause a chain reaction, pulling everything into chaos? I worry for my Grandchildren, not for me, I’m too long in the tooth to really be affected either way, but they will have to live with the disaster, whichever is the vote. I believe the majority of the under 25’s want to remain. I think we should listen to them a bit more perhaps.

I know one shouldn’t but let’s just look at one fact . I agree that we have been misled with a figure of £350m and that the true figure is £136m. Well I am pretty sure that £136 million per week will go along way to correcting many things in this country. Since I’m talking about money is it correct that the EU financial annual figures have not been scrutinised or agreed by any accountants ever since it’s inception . No wonder they want to keep it going .

£136m sounds like a lot of money but (a) it’s less than 1% of public spending so it won’t really help pay for very much and (b) do you really think Osborne wouldn’t just give it away in tax cuts for the rich?

In answer to your second question, that’s not true. http://www.richardcorbett.org.uk/the-eu-accounts-have-never-been-signed-off/

Well, if £136 million each week [£7 billion a year] does not sound like much to you then I am sure that this £7 billion each year would be appreciated by the National Health Service.

Of course it would be greatly appreciated by the NHS, but everyone knows that there isn’t a chance that all this money will go there. I doubt even 1% would go to it.

Brendan:

What a wild assertion.

Where do you get the 1% from?

My old teacher used to mark my work, “Must do better”.

What on earth makes you think that this government – with its record to date, including selling off much of the NHS on the quiet – would give even a penny to the NHS? Brendan is quite right : any money saved from the EU Budget would not go to the people who need it most.

TiddK:

And you know this because…………?

Oh, I see because you think so.

Fair enough [I suppose].

I know it because I’m a disabled person who’s experienced the brutal callousness of the IDS regime first hand. Therefore opinion has nothing to do with it. I’ve also experienced to inabillity to get many of the services freely available on the NHS some years ago, which now you have to pay for.

But then, sarcasm always gets in the way of properly human responses, doesn’t it (rhetorical).

TiddK:

Your outrage is your business but you are very wide of the mark no matter how much you fulminate.

If it is accepted that a post Brexit regime does not spend an extra £7 billion a year on the NHS that is saved forom EU taxes, well it is still there in our taxpayers pockets & not in EU coffers.

Is that bad?

Do not fight the wrong fight.

To describe my mild-mannered reply as “outrage” and “fulmination” says more about you than it does about me.

As for your analysis about the “7 billion” saved – well, even Boris now admits that that figure is statistically wrong but is (I quote) “a useful tool in the debate”.

If you are for BREXIT, then I’ve not picked the “wrong fight”. Far from it.

As far as I can see, my post has yet to be published! I wonder why? Could it be that the much vaunted LSE lecturer does not agree with what I said? In the past when arguing with left wing university types, their tactic is either to shout one down or to ignore completely the point made! So much for open debate! As open and fair as the proven bias of the BBC!

That’s a very short term view. Lets say in the worst case scenario that this government is actually super corrupt and just stealing money form the poor, in a few years time they will be out anyway.

Another government may use that money better and this time in 10 years we could have a perfect health system.

It seems economy is the latest buzz word to keep people towing the line and keep them in check. Every is being brainwashed to thinking that the 5th most powerful country in the world will implode without the EU. It will not – other countries have too much to lose to stop trading with us.

It’s equally short-term to think the EU is a completely unchanging monolith, whose shortcomings (and yes, they do exist!) will never be addressed. E.g. by Britain, among others.

The NHS staffed by many EU citizens you mean? What will you do when they are required to leave NHS employment?

Where did that come from?

Who wants to expel EU citizens excepting to expel convicted criminals [which we cannot presently do]?

No sensible person asks for that.

I do hope that you support the right to expel EU criminals.

May I refer back to the first question as I think a little mare understanding is required. You mention that Osborne will not do nice things with the money? If we leave the EU surely no one is foolish enough to think that Cameron and Osborne will keep their jobs? I mean I thought that bit was obvious.The Nation has had enough of them and there will be a vote of no confidence and they will be out of a job, I thought that was readily understood after all that is what Boris is doing, he wants the top job.

Yes but the point is that the 136 Pounds a week pale in comparison to the gains to the UK from free trade with the EU. That was the upshot of the recent IFS and OBR forecasts on the costs of Brexit, both based on the NIESR model: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/may/25/ifs-brexit-extend-austerity-budget-deficit-eu-referendum

Sorry, 136 million Pounds of course

One thing that always concerns me when the remain camp talk about the loss of trade deals is this. If the EU and Britain entered a tit for tat with import taxes etc. I think the CEO’s of BMW, Audi, Volkswagen would be straight on the phone to Angie. When Obama said we will go to the back of the queue (good luck in obtaining your Scottish Whisky USA) and that’s just for starters.

Quite right Charlie Robinson! Well said.

You are right about the German car industry phoning Merkel. However, the issue here are the threats by some EU countries and by the liars in the Stay campaign led by our less than illustrious leader, the Oxford oaf! Do we really wish to be linked with countries that spend much of their time threatening us?

Spain has invaded the territorial waters of Gibraltar in recent months. They have threatened to invade Gibraltar if the UK votes to leave! I trust that if we leave the EU our response to such an act of aggression would be immediate and overwhelming! As I have suggested elsewhere, I doubt the Spanish so called armed forces have the capacity to defeat Andorra much less the UK! However, their behaviour shows the contempt in which the EU generally holds GB.

The new dictator of Europe Frau Merkel has bullied other countries with relish. Look at how she has treated the Greeks. She has tried to force other European countries to accept huge numbers of immigrants and tried to stop them from taking steps to deter illegal immigrants.

Then there is the issue of corruption and financial misbehaviour within the EU. I suppose we have a similar problem here with thieving MPs and expenses. However, we have tried to tackle the problem. What has been done in the EU? NOTHING!

In my opinion, the EU is doomed. Please take a close look at what is happening in the US. The prelude to the election is tearing the country apart and the hatred, yes Hatred, on line is really scary. If you doubt what I say, please go online to check the forums such as this. The factions in the USA. have more in common than we do in Europe, so is it likely to happen here? Many countries in the EU hate Great Britain: France (Waterloo et al), Germany (WW1 and 2), Spain (the Armada and the Falkland Islands) just to mention the most obvious ones.

In conclusion, a trading partnership similar to that Norway has with other countries is the way to got and not the overbearing EU model.

In the unlikely that Spain invaded Gibraltar there is very little Militarily we could do about it. We have no aircraft carriers and no aircraft to put on them even if we had held on to Ark Royal.

Deploying a fleet even if we could (without air cover) is tactical suicide. Spain would have overland logistics chain we would not.

If Spain took Gibraltar by force we’d have to go to the International Courts and ask nicely for them to give it back.

I confess that I only worked as an MOD Analyst for a dozen years and so, given you appear to have expertise in everything else discussed on this thread, you could well trump me on this one.

Hi John,

Sarcasm is the lowest form of wit! As with most of the Remain campaign, if your argument is weak, as is your one, you revert to throwing insults about.

No, I am not a specialist in military matters, but I do have a couple of friends who are! Their opinion of the Spanish armed forces is not very high and I believe they would have a much better understanding of such matters than I do.

As I mentioned in a previous post, I have a number of Spanish friends. To say the least, they are not impressed with the Spanish Government’s threat to invade. One of my military friends has suggested that the Spanish armed forces would have to attack across a narrow front that is easy to defend. I suspect, though, that numbers would win the day for Spain. However, the aircraft we have can be supported by air to air refuelling and I believe there is an airport available in Gibraltar. My understanding is that their airforce is rather poor and ours is far better equipped.

As usual with remain supporters, you have missed the point! Perhaps you wish to associate yourself with a thuggish regime, but I do not! The Spanish Government, by making the threat of military aggression, has shown the world how they would behave if they had the power. Fortunately, they do not! Perhaps you ought to read the response by Basque-spaniards to one of my previous posts!

You say you work for the Ministry of Defence. I suggest, with your attempt to denigrate the British Armed Forces, you really should look for another type of work for it is clear you do not have the best interests of the UK at heart! The idea of one NATO country (Spain) attacking another NATO country (GB) would be rather extreme but that is what the Remain campaign is – extreme! I suspect, also, that the Russian “action man” would be delighted if that happened and is over the moon with the Spanish government’s threat. If he ever gets to read your comment on this site, perhaps he may offer a job!

Finally, your post shows a strong anti-democratic point of view! You never mentioned the people of Gibraltar who really do not want to be part of Spain and have repeatedly voted against Spanish control! Interestingly, if Spain did invade Gibraltar, their European Union membership could be challenged legally as respecting the status quo of Gibraltar was a key part of Spain’s application!

“Many countries in the EU hate Great Britain: France (Waterloo et al), Germany (WW1 and 2), Spain (the Armada and the Falkland Islands) just to mention the most obvious ones”

And of course USA (War of Independence), Japan (WW2) , China (Opium Wars) and some of our other new chums must hate us too by your logic.

By the way, we are the United Kingdom not Great Britain

Patrick, your observations are reasonable, but you overlook several points. Firstly, we lost the American War of Independence, so the Yanks are not so harsh on us. Secondly, the USA finished off Japan not Great Britain, so they are more fond of us. We buy a goodly number of Japanese cars, so that is in our favour. I could go on, but feel the point is made. By the way, it is not for you to dictate what we call this country! If I wish, I shall call it Great Britain.

Mike, you are confused.

GREAT BRITAIN consists of England, Scotland and Wales.

THE UNITED KINGDOM consists of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

I have to say, it is difficult to take your opinions seriously when you don’t know the name of your own country.

However you are of course free to continue to arrogantly use whatever term you like, even if it is incorrect……

Sorry Mike – it’s me again.

To use your logic- since we buy a goodly number of French and German cars, that must be in our favour.

Of course we also helped liberate France at the end of WW2, so that must be in our favour too. They might even have forgotten about Waterloo by now, who knows?

We help the Spanish economy with our millions of tourists so I suppose they might just about have forgiven us for the Armada.

I guess it could be argued that we were losing WW2 until the US joined us so, like the Japanese, the Germans might be more “fond of us”

However, Italy is another matter. They are still very sore about the way we attacked the Roman legions.

Hi Patrick,

I’m afraid I am very busy at the moment, so to be brief. Once again, nothing more than low level sarcasm from the Remain side.

Again, a very serious mistake in your post about how various nations like/dislike us. You say were were losing WW2 until the USA joined in on 8/12/1941.Ever heard of the Battle of Britain? Ever hear of a country called the Soviet Union (USSR)? I believe they had just a tiny part to play and lost more killed than UK, USA, Italy and Japan combined! The Russian action man will not be pleased with you! Please take great care, the Russians it seems may come after you with Plutonian or a sharp needle in an umbrella!

Do not know much about preChristian history in Europe, but believe it may have been the Huns who stopped the Legions of Rome.

If you really believe the EU loves us, then vote remain by all means, but don’t blame me when, in the near future, all he’ll breaks out in the EU.

Hi Mike

I am also very busy.

You seem to have a sense of humour failure. All this garbage about who likes us and who doesn’t, based on events that happened centuries ago, is just childish nonsense.

Again, a very serious mistake in your reply – as you respectfully admit, you don’t know much about pre-Christian history but I think you’ll find that there were no Huns in Britain in Roman times.

However, I am glad to see that you have not come back on the Great Britain v United Kingdom subject, so at least I have educated you a little bit!

Spain has not threatened to invade Gibraltar. Spain and the UK are both NATO members and there is absolutely no chance of conflict between them. Which you’d know if you knew anything at all about international relations, the subject of this article.

You’re doing great Mike. Thanks for all your arguments and reasoning. I’m in complete agreement with you !

I have been following this thread as I hoped to find some impartial information to help guide me in which way to vote next week, and have found myself experiencing a mix of emotions,especially at the comments of Mr Stringer. Initially I felt frustration that he seemed to jump in with his opinions apparently without reading other person’s threads in detail; then I felt increasing dismay at the low level of courtesy and high level of aggression in the various posts from a variety of contributors; then I moved on to increasing incredulity that such posts could actually appear on an LSE moderated thread; and then, I had a sudden moment of typical post-modern illumination and realised that I had hit on a new conspiracy theory! Mike Stringer is not a real person; the LSE moderators have created a spoof persona to ‘string’ us along by aggressively asserting the ‘Leave EU’ position, in such a way as to discredit the Leave position altogether. Genius! 😉

Baba – oh my I just love your reply!

Here’s the counter argument (i.e. in favour of Britain leaving the EU) if anyone’s interested: http://www.eureferendum.com/themarketsolution.pdf & the longer version: http://www.eureferendum.com/documents/flexcit.pdf

Yeah, but where are the credentials. Dr North’s qualifications are in public sector food-poisoning surveillance. In comparison to an LSE Professor, let’s restrict his opinions to that domain.

End of.

Having read the counter argument, I am even more convinced that we need to remain in the EU.

Dr Richard A E North – what are his credentials? Is he not also a climate change denier? Didn’t he destroy the career of Rajendra Pachauri, chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), accusing him of using his position for personal gain, only to be found totally wrong and the Telegraph having to retract the article and apologise?

Like his saying, “if being wrong gets one closer to the truth – as it does – then it is worth putting up half-formed speculation and letting the debate rage.” Clearly his little papers are wrong and misguided, but it has led to a very good article presented here by Nicholas Barr

I think one should bear in mind that the negotiated ‘opt-out’ from ‘ever-closer union’ doesn’t really have any legal force; it has not yet been voted on by the European Parliament, and in any case will not prevent future UK politicians into being pressured to agree to further political integration, possibly against the will of the majority of UK voters. (Interestingly, Graf Lambsdorff of the European Parliament seems to claim that any agreement secured by David Cameron from other members of the European Council was not legally binding – see http://www.euractiv.com/section/uk-europe/interview/graf-lambsdorff-eu-clearly-went-too-far-in-brexit-concessions/). It may not be wise in the long run for the UK to remain a member of the EU when the majority of European voters desire a far greater degree of political integration than the majority of UK voters.

Thank you for this intelligent and well-reasoned article, in which you back up your case by statistics, quotes and useful references.

It is such a pity that the Brexit case is so often made from a position of emotional reaction ranging from fury to fear, but usually uninformed by ‘inconvenient truths’.

David Ellis’s point about the negotiated opt-out is sound and definitely thought-provoking, but I do not think that – on its own – it provides a good enough case for leaving. There are too many other factors, of which the economic and security issues alone are too large to even consider turning our backs on.

The EU is a slow self fulfilling administration of mediocrity.

It takes years to agree on anything because each member state is concerned with its own interests.

It has failed to act cohesively over the refugee crisis.

It failed go fix the Ukraine crisis.