There has been much speculation that Britain’s vote to leave the EU will trigger its disintegration. Tim Oliver looks at various scenarios to consider whether this could happen. He maintains that rebuilding trust and relations between the UK and the EU will not be easy as there won’t be any sudden divorce in the first place. Instead of a simplistic narrative of in/out we need to think of future relations in terms of shades of grey.

There has been much speculation that Britain’s vote to leave the EU will trigger its disintegration. Tim Oliver looks at various scenarios to consider whether this could happen. He maintains that rebuilding trust and relations between the UK and the EU will not be easy as there won’t be any sudden divorce in the first place. Instead of a simplistic narrative of in/out we need to think of future relations in terms of shades of grey.

Britain’s vote to leave the EU has thrown up a host of questions about not only the future unity of the UK but of the EU itself. Brexit could be the tipping point for a Union that has faced crises in the Eurozone, Schengen, Ukraine, to say nothing of democratic, demographic, and productivity problems.

But the EU has survived numerous crises in the past, so why might this one be any different? After all, politics is often about crisis management and muddling through. And if there’s one thing that characterises the EU and crisis it’s muddling through.

A research paper published earlier in June of this year by the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB), in cooperation with the LSE’s EUROPP blog, set out various scenarios for life for the UK after the referendum. The ‘harsh Brexit’ scenario imagined a Brexit leading to geopolitical turbulence for the whole of Europe.

A harsh Brexit would unfold if trust collapses on all sides: where UK government becomes dysfunctional, UK-EU relations breakdown, and relations between remaining EU member states decline as they struggle to handle a Brexit and the other problems the Union faces.

These would build on a foundation of UK-EU relations (which have a long history of difficulties) reaching new lows in recent years, and where the EU’s internal relations have been stretched by crises in the Eurozone and Schengen.

Should such a harsh Brexit scenario unfold then it would show a UK, EU and Europe lacking much by way of solidarity, trust and unity. It is in such a situation that European disintegration becomes a possibility. However, a turbulent and harsh Brexit could also pave the way towards a more stable EU and UK-EU relationship.

Brexit, Grexit, we all fall down

A British exit will be handled through a series of overlapping negotiations, which create an ideal setup for division, delay and animosity. In the UK the process has already begun within the governing Conservative party to replace David Cameron, a process that could allow ongoing tensions over Europe to divide it.

The government – when it finally has clear leadership – will face the challenge of negotiations within the houses of Commons and Lords where a victorious Brexit side of the Conservative party may lack a majority to get through any exit deal it wants. There is a possibility of further referendums to settle the matter of what ‘leave’ means.

Negotiations will also need to take place with devolved governments and London over their constitutional and policy role in any exit (especially given Scotland, London and N Ireland voted to remain).

The UK and remaining EU members will need to set out their respective negotiating positions and attempt to reach a deal. But this will be limited by nobody quite knowing what either the UK government wants (which depends on who ends up leading it) or what the remaining EU itself wants given most member states had been banking on a remain vote. Brexit negotiations could consume the time and energy of all participants, distracting from and undermining cooperation in other areas.

A series of negotiations amongst the remaining 27 members have already begun to reach a deal over what to offer to the UK as an exit deal. Here the remaining EU will primarily struggle to balance ideas and interests.

One aim of the remaining EU will be to protect its unity – the idea of political integration, of ‘ever closer union’. This will be to deter any further attempts to break away; perhaps by limiting any economic links the UK can expect outside the EU meaning the UK can expect the worst possible economic losses from a Brexit.

Yet, some remaining EU states will struggle with the economic shock of losing one of the largest member states, a state that in 2014 ran a £61 billion trade deficit with the rest of the EU. For these states economic, and potentially security, interests will have to be taken into account.

Leadership throughout this will inevitably fall to the largest states such as Germany and France, but leaders in both face elections in 2017 and so will be limited in what they can offer by domestic politics.

Not to be overlooked are the likely demands of the EU’s institutions: the European Parliament (who will have to agree to any deal), a Commission that will provide the negotiating team and therefore try to push its own agenda, and a ECJ which depending on the outcome may have to rule on any deal.

The remaining EU will also need to find a way forward in managing a changed balance of power within the EU. The possibility of reshaping the Union’s policies in a host of areas may see some states manoeuvre to take advantage of the disappearance of one of the Union’s most liberal, free-trade and Eurosceptic members. There will inevitably be arguments over who makes up for the loss of the UK’s budgetary contributions (assuming any new UK-EU relationship is not akin to that held by Norway and so require the UK to continue contributing, albeit at a reduced rate).

Whether the remaining EU can maintain its unity and reach a deal with the UK depends largely on whether it can muddle through a Brexit. The crises the EU has faced over the past few years have been just as much about overall European unity; there has for example not simply been a refugee crisis facing Europe as much as a European crisis facing refugees. Nevertheless, the EU has successfully survived a series of crises in the Eurozone, Schengen and Ukraine through coping with them rather than solving them.

A Brexit would take the EU into uncharted and potentially more dangerous territory if it aligned with one or more of these crises (or a new one) that the EU has yet to solve. It is not beyond the realm of imagination to sketch out a scenario in which a Brexit and a Grexit at the same time strain the remaining EU to the point where key members such as Germany reappraise their approach to European unity and cooperation.

As one of the few pieces of theoretical literature on European disintegration noted, the EU has never faced a ‘crisis made in Germany’. All bets are off if Berlin loses faith in the current EU project as a result of a widespread break-down in EU solidarity and the increasing costs Germany is asked to carry to maintain EU unity.

Changes to Europe’s geopolitics would have knock-on effects for a host of relationships such as with the USA, Russia, Turkey and others.

Cruel to be Kind

It is, however, also possible to imagine Brexit leading to a more stable EU and a more settled UK-EU relationship. As historians often point out, the EU has often integrated in the face of crises and has been a more fluid organisation that can adapt more readily than many give it credit for.

A Brexit (and thus the disappearance of one of the EU’s most awkward members) in combination with one or more other crises could see the EU take the necessary steps for it to move from coping to shaping events.

The experiences of a harsh Brexit may also leave the UK more circumspect about what it can and cannot do in the world, and see an end to British politicians blaming the EU for many of the UK’s ills.

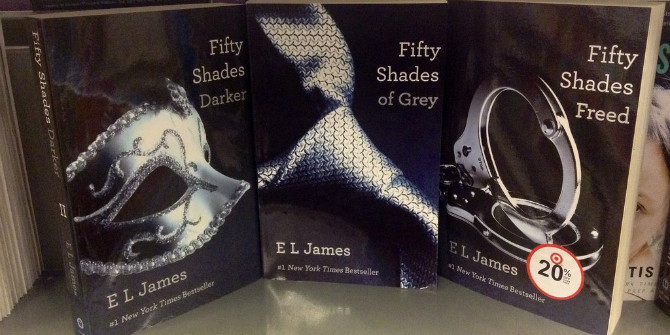

Fifty Shades of Brexit

Rebuilding trust and relations between the UK and the EU will not be easy. There won’t be any sudden divorce. Brexit is a process, not an event and the future of UK-EU relations will likely vary from area to area. Instead of a simplistic narrative of in/out we need to think of future relations in terms of shades of grey.

For the UK, the EU will remain the predominant organisation for European politics, economics and non-traditional security. For the EU, the UK will remain a European power of some standing, albeit reduced by its withdrawal.

Where then can both sides find a way forward so that trust is developed and stable relations ensured? The UK has traditionally played a leading role in foreign, security and defence matters and it is here that relations are likely to be pushed forward.

Despite Britain appearing to self-erase itself from developments over Ukraine, cooperation in foreign, security and defence matters (potentially through or enhanced by a more political NATO) remains one of the best means by which the UK and the EU can maintain working relations in future.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of BrexitVote, nor the LSE. Image credit.

Dr Tim Oliver is a Dahrendorf Postdoctoral Fellow on Europe-North American relations at LSE IDEAS

“Nevertheless, the EU has successfully survived a series of crises in the Eurozone, Schengen and Ukraine through coping with them rather than solving them.”

It is not as if these crises are behind the EU and it can move on … they have been piled one another upon the back of a camel just waiting for one last straw. Brexit may or may not be that straw.

The biggest flaw in the argumentation and reasoning of the Remain camp has been and continues to be an unquestioning assumption that the EU will continue as a viable going concern. If one dares to posit that it might not, then Brexit is a credibly rational winning move.

Britain has survived numerous crises in the past.Also, it is not in uncharted territory.Britain is used to running its own affairs.It used to manage an empire until the natives thought they were ready for independence.Brexit is not even a crisis, anyway.It is made out to be a crisis by the EU bureaucracy federalising globalising gravy train riders who can see that without the EU they may have to retire or try productive work for a living.

The EU, on the other hand, is indeed in a crisis.In fact, the EU is increasingly hamstrung by a calvacade of crises which it has no way of dealing with.The EU has long been in uncharted territory, unless one likens it to earlier more violent attempts to unify Europe.

There is much belly-aching over the stockmarket and the pound.Both are controlled and manipulated by interests which, by and large, see no easy pickings from an independent Britain.If Brexit goes ahead, the Scots will come back to Mother England or remain in the UK with a bit more independence.They lost heart the last time they had a chance to become independent.In the unlikely event of them getting out of the UK temporarily, they will have a fine time with the EU before the getting of wisdom.Rump UK will be alright.If that doesn’t work out, the rest of the West is already done for.