The Brexit vote is the most recent case of citizens in the west voting against an entire ruling class. What results is a rise of nationalism and xenophobia, but this may not be really what people have voted for. Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer argues that in today’s democracies, in the absence of a working public sphere, elections and referenda do not provide the space for citizens to show their discontent other than by overthrowing governments.

The Brexit vote is the most recent case of citizens in the west voting against an entire ruling class. What results is a rise of nationalism and xenophobia, but this may not be really what people have voted for. Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer argues that in today’s democracies, in the absence of a working public sphere, elections and referenda do not provide the space for citizens to show their discontent other than by overthrowing governments.

Back in 2015, the French woke up having to mobilise against the threat of Marine Le Pen’s National Front party, infamously nationalist and anti-immigrant, after its overwhelming victory in the first round of regional elections. Earlier that year, Poles elected a president endorsed by the Law and Justice party, openly nationalist and xenophobic, leading it to full governmental power as a result the parliamentary elections held several months later. The Austrians barely managed to fend off Freedom Party’s Norbert Hofer in the presidential elections held this spring. Most recently, another decision made directly by European citizens in a ballot ended in anti-EU Brexit. At the same time, in the United States Donald Trump is celebrating his popularity as the Republican Party’s presidential candidate, making sadly familiar-sounding claims about closing borders, throwing out immigrants, and making the country great again.

The pattern is not only similar in terms of exploiting the fear of others (whether it be Mexican workers in the US or Syrian refugees in Europe) an increasingly difficult job market, and frustration with the existing governments that have little to offer other than the politics as usual. However, what is even more striking and worrying is that numerous voters claim to be casting their ballot not for or against the policies offered, but as a way of expressing a general “no!” towards an entire political class that they feel has failed them, often blaming their shortcomings on international obligations. Still, the result of this outcry by the ballot box is not necessarily what the voting citizens aim for. The rapid rise of hate speech in public discussions is only one of many visible effects of opening the nationalist Pandora’s box, which many of the voters did not anticipate.

In France, the National Front has been gaining more and more voters by using xenophobic and anti-immigrant arguments. In Poland, Civic Platform was ousted from government by the Law and Justice party, which relied heavily on nationalist, anti-refugee rhetoric, despite the country’s macroeconomic good standing even during Europe’s economic crisis, and despite Poland’s negligible number of actual refugees. Nonetheless, it turned out that Civic Platform’s leaders were out of touch with popular sentiments; strongly believing everything was going well. Rational explanations didn’t work for the British citizens either, who preferred to leave the European Union with its migrant workers and unfamiliar Central-Eastern European languages rather than reap the profits of Union membership. But did the voters really want to leave the EU or enact xenophobic policies? During the presidential and parliamentary elections in Poland, the popular judgment was that of teaching a lesson to the eight-years-old Civic Platform led government, an eternity when it comes to Poland’s democratic political scene. In the UK, some people who had voted to leave the EU in the Brexit referendum are now suddenly baffled and upset that the country is destined to leave the Union. If so many citizens are disappointed with the consequences of their own vote, what did they actually vote for?

Looking at the success of the French National Front, Polish Law and Justice, Brexit, as well as the ongoing campaign of Donald Trump, the quick answer is that citizens are fed up with governments which fail to deliver what they had promised (for the most part boiling down to well-paying jobs and security) and which fail to communicate with the public. It is, in a sense, a vicious circle: if the government leaders were to explain their actions to the citizens, they would not be able to make extravagant promises. Yet, the common belief is that voters want to be charmed by visions of grand prosperity, regardless of their feasibility. If repeated and unfulfilled promises of individual affluence are no longer enough to make the voters happy, nationalistic pride proves an easier sell. Ideological visions are more long-lasting–being much less verifiable–than pragmatic, uninspiring policies, such as that of “warm water in the tap,” coined by Donald Tusk, former prime minster of the Civic Platform’s government, and current president of the European Council. His idea for the party’s rule was to have no grand ideas.

Yet, at least in Poland, voters have been seduced by the promise of a fundamental nation-centred change of more national pride and more national control, instead of imposed and supposedly destructive impact of international treaties. But they are suddenly stunned by the effectiveness of their own acts grounded in newly discovered jingoist sentiment. After the election results have rolled in and the political, economic, and social consequences of voting for radical nationalist change have stopped being merely a possibility, the voters are all at once claiming they did not want to elect what they had voted for (see for example). They just wanted to teach the ruling class a lesson.

However, public elections and referenda were not formulated as penalty cards, but as decisive profound change-making events. On the one hand, choosing more insulated, nationalist governments can be a sign that citizens want to have a stronger sense of control over their leaders. After all, the dominant populist narrative is that globalisation, international corporations, and the EU are imposing regulations on defenceless states, which have no choice but to conform. Yet on the other hand, with Habermas’ ideal of the public sphere and Schutz’s ideal of the well-informed citizen notably absent in contemporary life, if the citizens are unable or unwilling to control their governments more frequently than during elections, this is the only opportunity to show disappointment in a way that makes party leaders pay attention.

In the current form of democratic setup, how are citizens to show their discontent without demolishing governments or international treaties? The recent events suggest that political leaders need to listen not so much to generalising polls but to ordinary whistleblowers–demonstrators on the streets and haters online–far more carefully. Otherwise, after the voting is done, we end up throwing each other out with the bath water, when all we wanted was a cautionary splash.

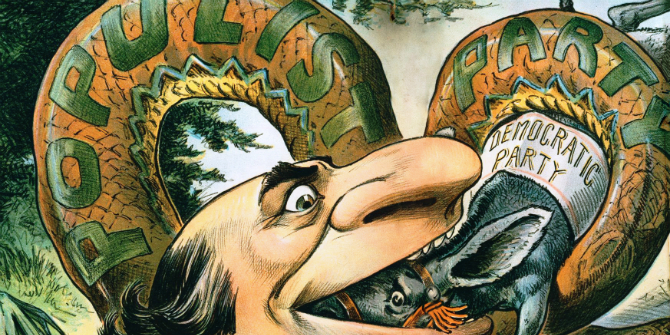

This article first appeared at the Public Seminar and it gives the views of the author, and not the position of BrexitVote, nor of the London School of Economics. Image: Public Domain.

Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer is Assistant Professor at Kozminski University, Warsaw; NYU Institute for Public Knowledge Visiting Scholar (2016); Editor-in-Chief of Tamara Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry; and New School for Social Research Alumna.

The author says that the Brits should have remained in the EU and ‘reap the profits of EU membership’. What profits? £20 billion a year gross for exactly what? The electorate was wiser than our academic apparatchiks.

Perhaps we should take Brecht’s advice and after elections simply change the ekectorate rather than governments.

Such a shame for our academic ruling class. Democracy brings results it cannot explain except by denouncing the people as stupid and xenophobic. Maybe an intelligent analysis of the failings of the EU would be more in order.

Not worth my time. energy or intellect responding to this drivel.

But you just did–clearly showing what little energy or intellect you have.