Why did Britain vote for Brexit? What was the relative importance of social class, age, and immigration? And to what extent did the vote for Brexit map on to past campaigns by the UK Independence Party? To answer these questions, Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath used aggregate-level data to analyse the Brexit vote in a paper forthcoming in Political Quarterly. They summarise the findings.

Why did Britain vote for Brexit? What was the relative importance of social class, age, and immigration? And to what extent did the vote for Brexit map on to past campaigns by the UK Independence Party? To answer these questions, Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath used aggregate-level data to analyse the Brexit vote in a paper forthcoming in Political Quarterly. They summarise the findings.

The referendum result is now well known. Leave won its strongest support in the West Midlands (59%), East Midlands (59%) and North East (58%) but attracted its weakest support in Scotland (38%), London (40%) and Northern Ireland (44%). The Leave vote surpassed 70% in 14 authorities, many of which had been previously targeted by Ukip, like Boston and Castle Point. Leave also polled strongly in Labour-held authorities in the north, winning over 65% in places like Hartlepool and Stoke-on-Trent. At the constituency level it has been estimated that while three-quarters of Conservative seats voted Leave, seven in ten Labour seats also did.

Such areas contrast sharply with strongholds of support for Remain, such as including Lambeth, Hackney, Haringey, Camden and Cambridge. Of the 50 authorities where the Remain vote was strongest, 39 were in London or Scotland.

Such results point toward deeper divides, like those outlined in earlier research on the ‘left behind’ voters who propelled UKIP into the mainstream. But to what extent was the vote to Leave the EU motivated by the same currents? To explore this question, we draw on data from 380 of 382 counting regions in the UK and link this to census data from 2011 (excluding Gibraltar and Northern Ireland for which we lack comparable data on some variables). Our analysis is based on aggregate data, so we need to be cautious about drawing inferences about individuals. Nonetheless, the data still provide a useful snapshot.

The Leave vote was much higher in authorities where there are substantial numbers of people who do not hold any qualifications, but much lower in areas that have a larger number of highly educated people. Fifteen of the 20 ‘least educated’ areas voted to leave the EU while every single one of the 20 ‘most educated’ areas voted to remain. In authorities with below average levels of education, Leave received 58% of the vote but in authorities with above average levels of education it received 49%. There were places where the Leave vote was lower than expected based on the average levels of education, which tended to be in Scotland and London. If we exclude London and Scotland from our analysis, then the association between education and the Leave vote becomes far stronger.

There is also a clearly identifiable though slightly weaker association between age and support for Leave. Of the 20 ‘youngest’ authorities 16 voted to Remain. By contrast the Leave vote was much stronger in older areas. Of the 20 oldest local authorities 19 voted to Leave.

What about ethnic diversity and immigration? Did appeals to end free movement have particular resonance in communities where there were large numbers of EU migrants? On the face of it, the answer appears to be no. Of the 20 places with the fewest EU migrants, 15 voted to leave. By contrast, of the 20 places with the most EU migrants 18 voted to remain. In many areas that were among the most receptive to Leave there were hardly any EU migrants at all.

We can get a clearer idea of the joint impact of these factors by carrying out a multivariate regression analysis. Table 1 presents results from a series of linear regression models. The dependent variable is support for Leave. In Model 1 education and age have a significant positive effect on the Leave vote. If anything, the effect of education on the Leave vote might have been slightly stronger than the effect of age (at least at the aggregate level). But even in places that had similar levels of education, support for Leave was noticeably higher in older communities than younger ones. By contrast, the level of European migration has a significant negative effect on the Leave vote. Places with many EU migrants tended to be less likely to vote Leave. Lastly, taking into account these factors the Leave vote was noticeably lower in London and Scotland. The results for Scotland are especially striking – the Leave vote was 22 points lower than what might have been expected given the level of immigration and educational and age profile of the country.

Multivariate Analysis of Support for Leave - linear regression

| Model 1: Great Britain | Model 2: England & Wales | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard error | Coefficient | Standard error | |

| % age 65 and over | 0.23** | 0.10 | 0.30** | 0.11 |

| % no qualifications | 1.12*** | 0.07 | 1.07*** | 0.08 |

| % EU migrants | -0.36* | 0.19 | -0.61** | 0.23 |

| Change in EU migrants | 0.51** | 0.19 | ||

| London | -7.34*** | 1.48 | -6.28*** | 1.58 |

| Scotland | -21.47*** | 1.12 | ||

| Constant | 27.11*** | 2.68 | 26.33 | 2.99 |

| N | 380 | 295 | ||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.68 | 0.62 |

Notes: *** denotes p<0.005; ** denotes p<0.05; * denotes p<0.10

It might be tempting to assume that immigration played no part in delivering Brexit. However, a slightly different picture emerges if we consider changes in levels of EU migration. Data on recent change is only available for England and Wales and so in Model 2 we restrict our analysis to this subset of cases. Controlling for the effect of overall migration and the other variables in Model 1 (excluding Scotland), those places which experienced an increase in EU migration over the last 10 years tended to be somewhat more likely to vote Leave (b=0.51; p=0.007). Thus, even though areas with relatively high levels of EU migration tended to be more pro-remain; those places which had experienced a sudden influx of EU migrants over the last 10 years tended to be more pro-Leave. This finding is consistent with the view that it is sudden changes in population that are most likely to fuel concern about immigration.

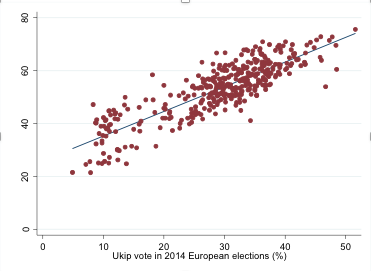

The results presented so far are consistent with research on Ukip, which emphasizes the party’s appeal among older, working-class, white voters who lack qualifications and skills. Thus, to a certain extent the factors that helped to explain rise of Ukip also help to explain why the British voted for Brexit. This comes out incredibly clearly in Figure 1, which considers the association between support for Ukip at the 2014 European Parliament elections and support for Brexit at the 2016 referendum. The R-square is 0.73, indicating a very strong relationship. By and large, then, authorities that were the most likely to vote for Brexit were the same ones that had given Ukip its strongest support two years earlier.

However, this clearly is not the whole story. Whereas the average support for Ukip across all authorities in 2014 was 29 per cent, the average support for Leave was 53 per cent. Where did these additional votes come from? Many insurgent parties start life by appealing to a narrow section of society but then, as they grow, they try to widen their appeal into new sections of society. Is this what Ukip’s populist Eurosceptic message achieved?

The answer is both yes and no. Places with older populations are both more likely to have voted for Ukip in 2014 and more likely to have voted Leave in 2016. However, support for Leave in 2016 is slightly less polarized along age lines (r = 0.34) than support for Ukip was in 2014 (r = 0.45). One explanation for this is that the Leave campaign managed to mobilise younger people than Ukip did. By contrast public support for Brexit (r = 0.53) is more polarized along education lines than support for Ukip was (r = 0.21). Thus, to a certain extent, the 2016 referendum result magnified class divisions within Britain that were already evident in earlier years, and which parties like Ukip had been actively cultivating. Lastly, support for Leave (r = -0.44) is slightly more polarized along immigration lines than even Ukip was in 2014 (r = -0.36). This points to the hardening of what some term a ‘cosmopolitan vs provincial’ divide.

Our analysis reveals how the 2016 referendum gave full expression to deeper divides in Britain that cut across generational, educational and class lines. The vote for Brexit was anchored predominantly, albeit not exclusively, in areas of the country that are filled with pensioners, low skilled and less well educated blue-collar workers and citizens who have been pushed to the margins not only by the economic transformation of the country, but by the values that have come to dominate a more socially liberal media and political class. In this respect the vote for Brexit was delivered by the ‘left behind’- social groups that are united by a general sense of insecurity, pessimism and marginalisation, who do not feel as though elites, whether in Brussels or Westminster, share their values, represent their interests and genuinely empathise with their intense angst about rapid change.

Interestingly, our results also reveal how turnout in the heartlands of Brexit was often higher than average, indicating that it is citizens who have long felt excluded from the mainstream consensus who used the referendum to voice their distinctive views not only about EU membership but a wider array of perceived threats to their national identity, values and ways of life.

Yet clearly the ‘left behind’ thesis cannot explain the entire Brexit vote. Even if support for EU membership is more polarised along education than support for Ukip ever was, the centre of gravity has shifted. This represents a puzzle. Public support for Euroscepticism has both widened and narrowed – it is now more widespread across the country, but in a number of important respects it is also more socially distinctive. In the shadow of the 2016 referendum stands one basic assertion that few would contest: Britain is now more divided than ever.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of BrexitVote, nor the LSE.

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent, and Associate Fellow at Chatham House. He is also a senior fellow at the UK in a Changing Europe project. His most recent book is the co-authored Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain (2014). @GoodwinMJ

Oliver Heath is Reader in Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Putting mining and manufacturing employment for 1981 in there will help capture the left behind element. See chart 3 here for the correlation for cities:

http://www.centreforcities.org/blog/six-charts-cities-eu-referendum-vote/

Full of fascinating insights but perhaps like too many other analyses treats voters as purely economic beings. Should be read in conjunction with the recent blog posting by Dennison and Carl.