Nicholas Barr, whose Letter to friends was read more than 425,000 times before the referendum, looks to the future – seeking a meeting ground between freedom of movement and control of immigration. He explains that the division is partly between younger and older people, partly between different parts of the UK, and partly between skilled and unskilled workers. He argues that EU negotiations are not enough, but need to be accompanied by wider policies to address the concerns of the losers from globalisation, to create a balanced discussion of migration, and to recognise the position of younger people and of Scotland and Ireland.

Nicholas Barr, whose Letter to friends was read more than 425,000 times before the referendum, looks to the future – seeking a meeting ground between freedom of movement and control of immigration. He explains that the division is partly between younger and older people, partly between different parts of the UK, and partly between skilled and unskilled workers. He argues that EU negotiations are not enough, but need to be accompanied by wider policies to address the concerns of the losers from globalisation, to create a balanced discussion of migration, and to recognise the position of younger people and of Scotland and Ireland.

Summary

My Letter to friends, posted in late May, explained why I would vote Remain. Since the referendum, many of the same friends have asked ‘What now?’

The specific ‘What now?’ is about relations with the EU and the wider world. Options include:

- ‘Norway’: remain in the EU single market but accept that this comes with free movement;

- ‘Canada’: a bilateral trade agreement with the EU, without free movement but accepting lower access to the EU market, particularly for services;

- Based on World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules without any specific agreement with the EU, but accepting significantly less access to the EU market.

Most of this note is not about making and implementing that choice – daunting though the task is – but about the implications for policy of the deep divisions that the referendum made clear.

- Between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas;

- Between Scotland and Northern Ireland and the rest of the country;

- Between people with more skills and those with fewer;

- Between older and younger people.

Those divisions mean that the agenda is much wider than negotiating a new relationship with the EU. It must also tackle at least three other areas:

- Sharing the gains from globalisation more equally;

- Ensuring an open, informed and balanced discussion of immigration and carefully-designed policy;

- Recognising the claims of groups who voted heavily to remain, notably younger people and the populations of Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Drivers of change

Technological change: Globalisation has benefits but leaves some people out

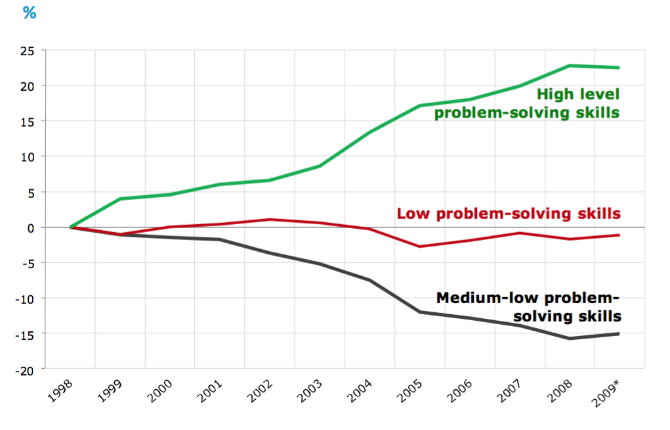

What economists call ‘skill-biased technical change’ has increased the demand for highly-skilled workers. As Figure 1 shows, employment of people with high-level problem-solving skills has increased, with a hollowing out of the demand for medium skills.

A second element is globalisation. A combination of free movement of capital and instant communication makes it easier for firms to move production abroad, creating downward pressure on wages, particularly for medium and lower skills.

Two conclusions stand out:

- Globalisation generally benefits countries by increasing trade.

- But the benefits do not flow evenly. Not all countries benefit (Economist, 6 February 2016). And within a country there can be losers, mainly those with lower skills.

Social change: Much progress, but also disagreement

In the 1950s people mostly got married and mostly stayed married, and mostly the men were the breadwinners. Male homosexuality was illegal. London underground trains had 5 smoking and 2 non-smoking carriages. Eating out was rare, and mostly fish and chips, Indian or Chinese. If you wanted wheelchair access, forget it. Boys collected cigarette cards of (mostly English) footballers. Amateur and professional cricketers had separate dressing rooms. Till 1956 there was only one television station. In the 1960s, with virtually no pop music on the BBC, pirate radio stations broadcast from offshore ships.

Today, family structures are more varied and more fluid: people get married (or not), and may divorce. There are women bishops, CEOs, airline pilots, and members of the MCC and (almost) all golf clubs. Gay marriage is legal; smoking in public places is not. Eating out is common and varied (the skittle alley in our village cricket club is out of action once a month for an oversubscribed evening of Thai food). Tickets for the London Paralympics sold out. Many boys (and some girls) wear Messi shirts (an Argentinian playing for a Spanish club). Unlimited music and videos are available via smartphones, and satellite dishes allow access to television globally.

Though many regard these changes as progress, there is disagreement. Some people think that change has not been fast enough, for example, unfinished business on gender equality. Others, including some older people and the digitally disadvantaged, regard change as too fast.

Immigration creates overall economic benefits, but also costs in some localities

Some facts. Despite their political importance, neither the flow of new immigrants nor the total of foreign born is out of line with other countries.

- In 2015, net immigration of EU citizens was 184,000 and of non-EU citizens 188,000 (Office for National Statistics 26 May 2016). Overall UK net migration was 2.54 per 1,000 persons; in the USA, Canada and Australia it was 3.86, 5.66 and 5.65 (World Factbook).

- In 2011, 13% of the UK population was foreign born (Office for National Statistics 2013). The figures for the USA, Canada and Australia were 13.5%, 21.3% and 21.9%.

The benefits of immigration. Historically there have been great benefits, from the Huguenots to today’s nurses, care-home workers and skilled researchers in the IT and biotech sectors. Immigrants are net fiscal contributors and ‘[t]he contributions of those who stay in Britain may well increase. It is a new form of foreign direct investment’ (Economist, 8 November 2014).

The argument that immigration reduces the number of jobs for Brits (economists call it the ‘lump of labour fallacy’) though intuitively plausible is wrong (see Nobel economist Paul Krugman, New York Times 7 October 2003). Instead, the job market adjusts – computerisation has not created a large army of unemployed former bank clerks. Overall, immigrants add to domestic demand, which helps to generate employment.

But not everyone benefits. A rapid rise in population – an increase in the domestic birth rate or immigration – can create bottlenecks in access to local services. The problem is not immigration per se, but population increase, particularly in smaller towns which cannot as easily attract more doctors, nurses and teachers (in contrast, London, with considerable immigration, has greatly improved school performance since the mid-1990s (Blanden et al. 2015)).

Who voted Leave

I have corresponded with people who voted Leave thoughtfully, for example to repatriate decisions currently taken at EU level. There are many such people. If that was the whole story, this note would be about future arrangements with the EU. But that is not the whole story. Many people voted to leave for very different reasons, and to get future policy right it is important to understand those reasons.

Globalisation. Alongside rising pay for the highly skilled, a large group of people experience low pay, zero-hour contracts, insecure jobs and austerity-driven benefit cuts, face a decline in social housing, and cannot even dream of getting on to the property ladder.

Immigration. An overlapping group see immigration as harming their job prospects. The counter argument is that it is not immigrants who are responsible for zero-hour contracts, but successive governments who have chosen to compete with flexible labour laws and low, tax-subsidised wages, rather than (as in Germany) through high investment in skills.

Others worry about immigration for less specific reasons, with evidence that those less exposed to immigration are most opposed to it. Large cities with many immigrants, including London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool and Bristol, all voted heavily for Remain. Whatever the facts, resentment is a reality that policy cannot and should not ignore.

Social change. A further overlapping group, many of them older people, see British culture changing in ways that they do not like.

In sum. A person might vote leave out of anger even if not in their economic interest. But that makes it sound as though people voted irrationally. Instead, policy must recognise that if people regard themselves as losers from globalisation, it is rational to vote against more of the same. The area that voted most heavily to leave was Boston in the East Midlands.

‘The median income in Boston is less than £17,000 [the national average is over £26,000 (Office for National Statistics)] and one in three people have no formal qualifications… Filled with disadvantaged, working-class Britons who do not feel as though they have been winning from European integration, immigration, and the global market, Boston turned its back firmly on the status quo’ (Matthew Goodwin, UK in a changing Europe 4 July 2016).

The same, highly recommended, article quotes Robert Ford’s explanation to those of us who voted Remain of the way the world looks in places like Boston:

‘Feeling upset by wrenching social change that has been imposed on you by people whose values you don’t share or understand? Now you know how UKIP voters have felt’.

Who voted Remain

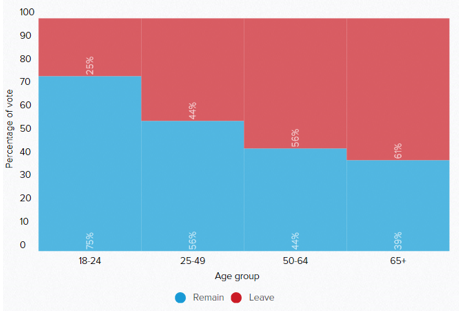

Younger people. As Figure 2 shows, 75% of voters between 18 and 24 voted to remain.

‘[T]he younger generation has lost the right to live and work in 27 other countries. We will never know the full extent of the lost opportunities, friendships, marriages and experiences we will be denied. Freedom of movement was taken away by our parents, uncles, and grandparents in a parting blow to a generation that was already drowning in the debts of our predecessors’ (reader comment, Financial Times, 24 June 2016, heavily quoted on Twitter).

Such cries of distress are the mirror-image of those in the previous paragraph.

Source: Politico, based on a YouGov exit poll

Turnout for the 18-24 group was almost double the figure initially reported.

‘At a rate not seen for two decades, 64 per cent of the age bracket opted to vote on June 23, based on in-depth polling … analysed by professor of political science and European politics Michael Bruter and Dr Sarah Harrison of the LSE’ (Independent 10 July 2016).

This is a generation who understands how connected the world is today. A 24-year-old was born after I got my first email address. They have grown up online. With a few clicks they can share what people in other countries are wearing and listening to. They take Facetime and Snapchat as a natural part of their world. They take it for granted that the Premiership has many foreign players. They travel widely.

They feel angry. They will feel more angry when they face the realities of applying for a French work permit, or when their European boyfriend’s or girlfriend’s student visa expires and they cannot stay and work in Britain.

‘So what?’, some might answer. One response is intergenerational fairness – giving young people as good a start as possible. A more mundane answer is potential economic damage:

- The loss of visa-free work makes it harder for UK firms to recruit from a large talent pool (all the more since such recruitment often starts on an informal temporary basis);

- And a decline in the attractiveness of the UK labour market risks the loss of skilled British workers to more attractive international environments elsewhere.

Science, which is highly internationally collaborative, faces the same risks (see BBC 19 July 2016). The loss of free movement makes the UK a less good base, simultaneously reducing the inflow of scientists and increasing the likelihood that British scientists will choose to work elsewhere.

Scotland and Northern Ireland. Every voting district in Scotland voted to remain. A second Scottish referendum could have a different result from 2014.

The Northern Ireland vote to remain was largely concerned with the Irish peace process (see Guardian 19 July 2016). With both parts of Ireland in the EU, people shop on either side of the border depending on the pound/Euro exchange rate. UK exit puts at risk free movement, a key element in the peace process. It is not surprising that the number of applications by Northern Ireland residents for Republic of Ireland passports has generated a plea for patience from the Republic’s passport authority.

What to do about it

How did this happen?

- People on the rough end of globalisation are angry, but did not wish or intend to harm the young.

- Many older people are angry: they may feel misled in the 1975 referendum or may be unhappy at social change. But mostly they did not intend to harm the young.

- Many young people are angry but do not condone the failure to address the downside of globalisation.

- Governments in other countries are angry that a schism in the UK is taking up so much of the international agenda when so much else needs attention.

But anger is not a policy. Policy needs to address a genuine conflict of world view: the flip side of ‘gaining control of our borders’ is reducing the right of younger people to live and work in 30 countries (the UK, the EU, Norway and Switzerland).

Globalisation: More attention to the needs of losers

If globalisation creates overall benefits but at the expense of some groups, it is good economics, good politics and good social policy to share the benefits more equitably. We have not done so, instead cutting benefits for the working poor and reducing social housing.

Policies should include:

- More and better vocational training to increase skills;

- More generous in-work benefits in the short run, and over the medium term a higher minimum wage and reduction of zero-hour contracts and casual labour;

- Better support for people seeking work;

- Improved family support;

- Policies, including housing policy, addressed at poor communities as a whole.

These policy areas all need more resources and a longer-term view of policy.

The argument for higher spending on these areas is based not only on social justice, about which views can differ, but on tackling the divisions which the referendum brought out so vividly.

‘Mrs May needs to win over the disaffected millions who chose to leave the EU as a protest and who in recent years have seen no improvement — even a worsening — of their prospects’ (Financial Times, 15 July 2016).

In emphasising the needs of the less-well off on the day she took office, the Prime Minister’s statement explicitly recognised the point.

Immigration: A ‘proper’ discussion and carefully-designed policy

Immigration benefits the country as a whole but creates resentment for several reasons.

- ‘[The campaign] released a latent racism and xenophobia in all sectors, and challenges the prevailing consensus of tolerance and acceptance’ (the Archbishop of Canterbury, quoted in the Guardian, 8 July 2016).

- Discussions of health include the ‘worried well’ – people who are worried about their health when there is no need. The analogue are people who think that immigration harms their prospects, or might do so, when that is not the case.

- A third problem arises if a rapid increase in population stretches local services.

As with globalisation, successive governments have failed badly. Many politicians have not contradicted a culture in which immigrants are blamed for social problems not of their making. Because immigration is politically contentious, few politicians have pointed out its benefits, e.g. the 100,000 EU citizens working in health and social care, or that the UK has less immigration than the USA, Canada and Australia. Failure of political leadership has prevented balanced, realistic and humane discussion.

This diagnosis suggests the following policy directions.

- Robust rejection of racism and xenophobia.

- Dissemination of credible facts and independent analysis to ease misplaced worries.

- Policies that address local pressures on social services, on which government has done a very bad job. In 2008, the government created a Migration Impacts Fund to provide extra resources to local authorities with rapidly rising populations. But the fund was small (about £35m per year), abolished in 2010 and reinstated in 2015. The policy is right, but the scale needs to be greatly increased.

- Wider policies to address immigration include a medium-term view of training. Short-term spending cuts, for example for training nurses, has led to hiring more nurses from other EU countries.

Free movement: Policies that respect the aspirations of young people, Scotland and Ireland

The best way to accommodate the young, the Scots and the Irish is to continue to allow free movement. But the only way to contain immigration is to introduce some new controls.

Assessing the balance between free movement and control of immigration should take account not only of the costs of access to the single market, such as the net UK fiscal contribution and the acknowledged problems of the EU, but also its benefits. Membership of the world’s largest market brings direct economic benefits, greater influence over trade rules and greater leverage in negotiations with third parties. The single market is so large that no other trading power can ignore its clout in negotiations. And as discussed, Brits also benefit from immigration, and many benefit from living in other EU countries.

A partial solution is a proposal by my LSE colleague Richard Bronk to exclude students and young graduates from net-migration numbers and exempt students and recent graduates of bona fide university courses below, say, the age of 31 from tougher post-Brexit entry rules. Youth mobility is hugely valuable for the UK: it creates high-skill networks, helps project UK soft power, and contributes to the economy by allowing firms and universities to hire recent graduates on short-term basis. Crucially, these advantages put little or no pressure on places that feel threatened by immigration. Bronk points out that youth mobility is already a well-established concept in UK immigration law, with a long-standing scheme allowing young people from countries including Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Japan and Taiwan to work in the UK for up to two years below the age of 31. Youth mobility assists the life-chances of young people and also the UK’s social and economic integration with its European neighbours.

In a fuller solution, sometimes referred to as ‘Norway-plus’ (Economist 2 July 2016), the UK would remain part of the single market but with some control over numbers to prevent peaks. Ideally, such control would be an agreement that all member states could introduce some flexibility. The argument is that a freedom that is desirable in principle and was workable in practice for an EU comprising six countries with similar incomes is a less-good fit for 30 countries with widely different incomes, when movements of large numbers of people create pressures in recipient countries while depriving lower-income countries of some of their most dynamic young people. Introducing some control over numbers would be a strategic change that would have to be justified in terms of its benefits to the EU as a whole.

To end on a personal note, having spent my career teaching the (mostly) young and writing about the role of the welfare state in tackling disadvantage, the clash between the losers from globalisation, concerned about immigration, and the young, who want free movement, is particularly vivid. ‘Norway-plus’ does not give either side everything it wants, but does provide a genuine meeting ground. Any other solution will perpetuate existing divisions.

A minimal reading list

On diagnosis:

Matthew Goodwin, Why Britain backed Brexit

Andrew Higgins, ‘Wigan’s Road to ‘Brexit’: Anger, Loss and Class Resentments’ New York Times, 5 July 2016

On ways forward:

Martin Wolf, ‘Global elites must heed the warning of populist rage’, Financial Times 19 July 2016.

Leader in the Economist 2 July 2016

Richard Bronk, Let young people move: why any post-Brexit migration deal must safeguard youth mobility

I am grateful to Alok Basu, Philip Bronk, Richard Bronk, Craig Pickering, Howard Glennerster, Abby Innes, Anne Lapping, Ros Taylor and Eiko Thielemann for helpful comments on earlier versions. Remaining errors and the views expressed are my responsibility.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.

Nicholas Barr’s Letter to friends: this is why I will vote Remain in the referendum.

Nicholas Barr is Professor of Public Economics at the European Institute of the LSE. Email N.Barr@lse.ac.uk.

Full of fascinating information but like many Remain commentaries simply treats voters as economic beings. I think it should be read in conjunction with the recent blog posting by Dennison and Carl.

The most likely outcome of Brexit is that the UK joins EFTA/EEA since that would offer a reasonable compromise between Remainers & Leavers. There is no reason why the UK could not agree some form of opt out on FoM. A precedent for this has already been set by Liechtenstein which has had such an agreement in place ever since it gained access to the single market.

As a leave voter I’m fraid I find this quite arrogant and misunderstanding of most of those I know who voted Leave. If the EU were truly democratically responsive that would be one thing but actually it isn’t. Its seemed fince 1975 like a machine rolling forward irrespective of its effects on its member populations towards ‘ever greater union’ and Cameron’s pitiful negotiation results last year simply demonstrated that. I wasn’t expecting Cameron’s government to collapse without any plan ‘B’ immediately after the referendum. I was expecting it to take cognisance of the referendum result and get on with Government in light of that. Furthermore I’m afraid it isn’t for me mainly about the economics. That is the mistake so many politicians and economists make. There is much more to people than their value to the economy as units of work. The British history and experience of the European continent is in many important ways fundamentally different to that of Europeans who have within living memory lived through warfare and/ or Communist repression on their streets and borders, on a scale beyond imagination here. This makes their priorities. tolerances and drives very different, which in turn affects their response-reaction to & participation in the EU machine. I genuinely believe that Britain will fare better outsid the EU, even assuming that the EU manages not to collapse inward and drag all its members down with it. Lastly I think that politicians and economists within UK as part of EU are so distracted looking across the water that it is how and why they have so completely lost touch with their electorate as to behave the way they did in the Campaigns – especially the Remain project fear campaign. Perhaps now they will realise they need to get back to mixing with everyone they represent and start understanding them from the inside again. I certainly hope so because if not the upheavals we have seen so far in the two main parties will be as nothing compared with what will be to come.

Genuine belief is not a terribly convincing argument! If your beliefs are wrong then being genuine does not enhance them! In any case, who ever admitted that their belief is not genuine? Have you one single piece of evidence to justify your belief? Perhaps, when you discover that you and all your co-Leavers have caused a result you never imagined, you will have the grace to apologise to the rest of the country. Sadly, by then the damage may be irreversible.

Although Leave voters were not a homogenous entity it is generally accepted that immigration was for the majority the most important factor.Furthermore the forthcoming brexit negotiations seem to be predicated on the tradeoff between FoM and access to the market.may I just point out the illogicality of this position.

The Eu four freedoms are free trade in goods,services and free movement of capital and people.Yet because we want three of those and restrictions on free movement of people, the Eu can’t grant it because we would be getting a better deal or to dissuade others getting the same deal. So the implication is that restrictions on free movement is better than unfettered free movement,indeed nations who prefer free movement would welcome other nations imposing restrictions as they would have a greater pool of immigrants wishing to come to them rather than competing with all the Eu nations.

The penny will eventually drop, the truth of the matter is of course that free movement of people is a relic of its time.Free movement worked when all Eu nations were in the same state of development and until the accession of Poland,the Baltic states Bulgaria and Romania,net migration was in the 1000s and even negative.

Eventually other countries will realize the best deal for them is to take control of their own immigration policy,one option for us is to allow immigration if there is a contract for at least three years at a certain salary rather than allowing migrants to just arrive and take advantage of our lightly regulated and flexible labour market pushing down wages in the low skilled sector.

I found this a most stimulating and insightful paper. The analysis and explanations were particularly good but “what to about it” less so. So I felt i was left hanging from a sky hook. Famously in change management circles the expression is that change is possible when “there is shared dissatisfaction with the present state, shared vision of the desired future state and understanding of the first practical steps: all of which should outweigh the pain and grief caused by any major change”. I would be delighted if Nick Barr were to apply his manifest abilities to the first practical steps, or even the whole equation. Perhaps an extra page beginning. “And so…..”

Excellent letter, thank you.

I would add two important elements – [1] our friends in the the North; [2] inflated housing costs due to undersupply, partially stoked in London by capital inflow from various parts of the world, whether laundering ill-gotten gains or fight to a ‘safe haven’ (ironically given Brexit).

The North has a population of 14million, who deserted Labour in droves both this and last year (driven by ‘vote Labour-Ed get SNP-Nicola/Alex’ hysteria) – they do not appreciate special pleading by the far smaller Scotland and Ulster, and they do feel the crunch on public services. While immigration is relatively low in many northern post-industrial towns, deprivation is very high and they are over-reliant on the austerity-shrivelled public sector. Traditional university cities voted Remain, towns did not, Racism misdirected towards the EU (when often aimed towards 2nd generation immigrants fuelled by the terrible crimes in Rochdale, Rotherham etc.) may have been a factor here. The ONS stats on live births to 2nd generation immigrants are indicative of those pressures dismissed by PM Brown in 2010 as “that bigoted woman”. Note these areas absorbed most of the mass Irish immigration in the 1840-1980 period. But adjustment is slow and the pace of 1997-2016 migration is unprecedented in the modern era.

[2] Housing costs – not the social housing you discuss – are insanely high compared to average earnings, especially in the Midlands and South, and rents even more so, That causes enormous resentment towards any factors responsible for under-supply. This is a chronic 30 year old problem begun by Thatcher’s selling off of council houses without replacement. Private landlords and enormous mortgages may be odd bedfellows for a Brexit vote, but those in the 25-45 age group particularly feel this agony, and may easily blame the enormous increase in EU migrants without any apparent supply increase for their travails. England is not a fast-growing economy with (relatively) more land to build houses, unlike the US, Canada, Australia.

But despite these rock-solid resentments, I suspect we will never leave properly, and as you suggest EEA-lite with some kind of restriction on free movement for many years is still most likely.

On the age distribution of voting, two thoughts:

1. there seems to have been little comment on the fact that the strongest anti-EU vote was from those who had had a chance to vote for the EEC, and did so by 3:1 in the ’70s. Some reflection on what has caused them to change their minds would surely be instructive?

2. I see you are (loyally) treating the Bruter/Harrison study on voter turnout as being definitive. Given that it was based on post referendum polling, of a group that clearly felt damaged by the vote, the likelihood of truthfulness in responses must clearly be highly doubtful. The 36% turnout figure was obviously too low- and based on the last election- but mid-60s doesn’t map with the age distribution vs turnout stats which are the best we concretely can go on. Around 50 seems more likely.

My background, many years ago was in Operational Research. The conclusion in many cases was that opposed points of view, such as those between the EU and the UK over freedom of movement, result from a fault in the system.

Since the Treaty of Rome was signed 60 years ago the aim has been to eliminate obstacles to free movement but the visionaries who drafted that treaty saw that the pendulum could swing in the other direction too.

That’s why they wrote that the European Parliament and the Council shall set up machinery to achieve a balance between supply and demand in the employment market in such a way as to avoid serious threats to the standard of living and level of employment in the various regions and industries, see TFEU 46 (d).

Regulation 492/2011 which implements Article 46 says nothing about these threats.

Public discussion about immigration tends to be about numbers per annum but the critical question is whether cumulative net immigration has brought the labour market into balance in each sector and community. Once it goes beyond that point problems will result and that is what seems to have happened.

In other words the threats envisaged in the Treaty of Rome have now emerged. The EU and the Government are obliged to act.

This article makes no reference to the democratic deficit (aside from the phrase about repatriation of decisions taken at the EU level). This article makes no reference to the subsequent disfranchisement and frustration of the population. Neither does this article discuss the issues around the primacy of the UK judiciary. There are also concerns about the negative impact the process of EU law harmonisation may have on our common law system. These are very important points, especially democratic accountability and our judiciary. This is well illustrated by the highly effective cut through of the leave campaign phrase of “Vote Leave, take back control”.

The focus of this article towards globalisation and migration paints remain voters as people of “Little England”. This may be true in some cases but is far from the whole picture. The UK is, generally speaking, a liberal and outward looking country. It simply cannot be that 52% of the country are small minded.

I am very hightly skilled and relatively young at the age of 37. I am a winner from globalisation and migration. Yet I voted leave for the reasons I mention – democratic accountability and the primacy of UK law.

I would be very happy with a relationship with the EU that consisted of free trade, free movement of labour (this is a little different from freemovemet of people) and full co-operation on defense and security. It escapes me why people think we need a political union for any of those things.

I think this article was flawed given the gaps I mention.

What Callum Hibbert illustrates is that economics and sovereignty were the two sides of the referendum coin. Many wanted both. But for migration the result might have been close to 50:50. This would have reflected the dilemma posed in the question rather than a divided nation. My wife voted leave with Callum and I voted remain with Nicholas Barr.

The question now is whether Brexit can mean better for Europe and better for UK. That can be the case if the withdrawal of the UK leads to a stronger EU.

That depends on resolving the issues surrounding free movement of people. As President Juncker says rights carry obligations. Has anyone spelled out those obligations or on whose shoulders they should fall?

Nicholas Barr mentioned a fund of £35 million for communities to deal with the effects of migration. That is £35 per head if it relates to (say) one million migrants, nothing at all in comparison with the cost of providing, services, housing and infrastructure. As Nicholas Barr argues the economy adjusts in the long run but there are significant factors in the short term.

I have suggested that the Commission set up a concerted action to deal with the issues of free movement. President Juncker has replied politely but it remains to be seen whether Brussels will take up the proposal.

A stronger EU? The ruling class might want that but what about the demos? What evidence is there that the citizens of Europe want this?

No doubt there are different ways the EU 27 could reorganise themselves to be stronger economically and in the eyes of their citizens. The withdrawal of the UK from full membership may faciltate the debate and reform.

Let’s not get carried away. ‘Free movement’ is of ‘labour’, not simply ‘persons’. Therefor this £35 per, is a misnomer; for some – if not many, of these migrants are here in the UK to deliver those very services.

A ‘stronger’ EU was/is inevitable. Few in the referendum ‘debate’ were arguing for or against the status quo: Rather it was for or against the relative future-possibilities of an EU going forward – with or without the UK, and those same possibilities of the UK going it alone.

The UK ‘elites’ (call them what you will) saw the writing on the wall – their gig was up.

Their bending of the will of the EU was fast becoming ineffectual:Hence the nonsense of the referendum and its aftermath.

Whether the EU (27) has the courage to forge a new future for itself, is a question I am not yet prepared to contemplate – as it will inevitably set the EU27 against the UK1 – part of which I shall constitute, if/when Brexit is realized.

However, if the EU28 can be reaffirmed, the future looks much brighter, for us all.

The idea of this referendum, the promise of this referendum and the having of it, each and all, accomplished every aim and objective of it.

i.e. The Conservative Party attained power and has kept it.

No matter how the ‘Leave’ vote is dissected and sieved; every perceived wrong had (and has) its origins here in the UK: From globalization to immigration. The very idea of EU expansion into the former Soviet Bloc has a Union Jack wrapped around it.

A vote for Brexit was a vote for all the perceived ills thought to have emanated from the EU.

It appears yet, that the main hope for UK success in an EU-free future comes from the EU’s demise – from the ruination of millions of lives:From damage done to the very people we each have so much in common with, for the pleasure and continued wellbeing of those whose historic disdain for us all is soon to be brought home to us again.

I am one that refuses to sit and fiddle while watching a certain future burn – to the strains of ‘Smoke gets in your eyes.’

Brexit:Up with this I shall not put!

https://www.change.org/p/jeremy-corbyn-mp-brexit-up-with-this-i-shall-not-put

Dear Tom,

totally agree with you and I hope we find back together after this populist old fashioned mis judgement. Thank you for your comment.

Thank you Damian. The road back to sanity may be more rough than long, but it is to a worthy end.

Not as good as the first Dear Friends, although it rightly puts immigration in context.

Leaving aside the unexceptionable Goodwin et al recognition of the English UKIP-led phenomenon since before the Euro-election of 2009 (like the EU referendum also proportional) the question What Next? needs to answer the fundamental failure of the British establishment to identify the benefits of EU membership beyond the Single Market.

Another LSE analysis examined the values inherent in voting on June 23 and discovered high salience between Leave voters and a predilection for the restoration of capital punishment. With Brexit anything is possible. The world is unstable and Brexit has made things worse. Britain’s voice is being stilled, its interests undermined as others exploit our new weakness.

Those of us who remember what being Out was really like must organise and use our experience to restore the status quo through more reliable, if faulty, democratic processes. England failed the United Kingdom on June 23: it needs full membership of the EU properly to influence events at home and abroad more than ever.

Edward McMillan-Scott

Patron, European Movement UK

Care to write a rejoinder? – Ros r.taylor6@lse.ac.uk

That was a very prescient comment. Only a few days after you posted this Paul Nuttall made reintroduction of the death penalty part of his platform for UKIP leader.

The Uk seems stuck in the past. We need to join our market power to be a serious stakeholder in a world that is shrinking. There is no way around reforming Europe together. The Uks special role, special relationship and special commonwealth are pipedreams of times long gone. Love the Uk and feel sorry for all of us in Europe having to waste endless bureaucratic capital allocation to figure out what this special UK Europe relationship should look like. Very poor judgment and nationalistic outdated choice.

This fails to consider that the economic forecasts weren’t trusted, and some people (e.g. Dyson) think that the EU tends to support Global Corporates and squeeze out smaller companies by having so many lobbyists sniffing around their Directive compilers – which end up as instructions which are superior to our national law. Hence the EU will always foster slow growth – and never reach the economic forecasts we’re given.

It also debases the Sovereignty argument which many Leavers claim was the main point. I, for one, believe we need to have direct access to representatives who can change the detail when it fails to work for UK.

I’m not sure I completely with the analysis. Older people have got richer while younger people have got poorer. So it’s hard to argue that it was economics behind the decision.

Which leads me to an alternative proposition for the way forward. Let’s break the UK up with Scotland remaining in the EU and England and Wales exiting.

People and companies can then choose which part they want to be in. There would no doubt be a bit of a traffic in both directions over the border with a cut-off date agreed after which movement would be restricted.

It would also provide an experiment in the way that East Germany and West Germany did and over a couple of decades would provide proof one way or another of the economics. It would also respect the views of both sides of the debate.

Given that 74% of Scots think Scotland will become independent in due course I think this is quite a likely outcome.