The social divide between Leavers and Remainers is striking. Proposals for a second referendum fails to understand the cause of the result: many feel that they have no influence over the immediate circumstances that surround them. But it’s not just the ‘48%’ who need to understand these drivers, writes Tony Hockley, but UK and EU elites alike: it is time to start thinking about the reforms that will address this widespread division and discontent.

The social divide between Leavers and Remainers is striking. Proposals for a second referendum fails to understand the cause of the result: many feel that they have no influence over the immediate circumstances that surround them. But it’s not just the ‘48%’ who need to understand these drivers, writes Tony Hockley, but UK and EU elites alike: it is time to start thinking about the reforms that will address this widespread division and discontent.

Many of those who now complain about the referendum result personally know no-one who voted for Brexit. Think about this for a moment and the result begins to make sense. Think about it for a little longer and the idea of signing a petition for another vote becomes the worst loser response, not the best. Social group AB voted to remain. The remainder of the country did not. Put in more crude terms, those with money – of all ages – voted Remain, those without voted Leave. Calls for another referendum, a general election, or for Parliament to reject the result will rightly be seen as another attempt by privileged groups to assert their authority over the rest.

A decent job and relative affluence provide autonomy; at work, at home, and above all over the social circle that is inhabited. Within every area that voted to leave the EU there will still be shocked, isolated groups of ABs who see only the benefits of unfettered free movement in Europe, and worry about economic growth. For others the shock is from how much the identity of their community has changed, how quickly, how little they have gained from this, and how little influence they have had. They feel stripped of autonomy.

Since 2010, the government has pursued policies to devolve control to individuals and communities. Directly-elected mayors and police and crime commissioners, and the ability to create new “free schools” are all attempts to foster local engagement in decisions that affect daily life. In January 2016, David Cameron announced a new strategy to regenerate run-down council estates, concerned that those who could move out had done so, leaving behind those unable to do so. The crumbling buildings of the estates of the 1960s can and will be improved. But the established social identity of many communities has also been crumbling, with no strategy for its replacement. Social identities matter. Humans are herd animals and social identity determines a large part of individual behaviour. It can be a force for good, binding communities together in social engagement, or a force for division when a community feels threatened.

Whilst the benefits of free movement are spread wide, the costs tend to be very concentrated.

I recently revisited the council estate of my 1970s childhood in Southampton. Until I walked down my old high street I had not understood the rising discontent about migration. Whilst the benefits of free movement are spread wide, the costs tend to be very concentrated. Population data for my old council ward shows that in the decade to 2011 there was an unprecedented influx of almost 2000 new residents who had been born overseas, about half of these came from Poland. This will have affected local homes, schools, shops, and jobs.

Even ward-level data on migration hides the full-scale of the localised and rapid change that has taken place. Good or bad it is an external force over which no-one in Britain has any influence. It is human nature to attach greater value to what is already possessed rather than what might be gained from change, known as the “endowment effect”. It is also human nature to prefer self-determination over control. That is why so many were motivated to vote for Brexit. These issues are not unique to one ward in Southampton, which is by no means an extreme case, but are being felt across the EU. It is clear that a referendum in any other member state could produce a similar response.

The European “project” was designed within a world of sparring blocs of developed countries. These countries were the source of world economic growth and social advance. Since then there has been the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, trade globalisation and fragmentation, and the single currency experiment. Excess confidence in the European project is based on an assessment of the past, and not of the future. The whole concept of a federal European bloc is looking dated and dangerous. It is too distant, and too inflexible. As the referendum has shown, handouts from the EU budget to deprived communities are no compensation for the loss of control. The message of the Leave campaign to “Take back control” proved to be particularly salient amongst affected communities. Those who have control over their own lives – because they have money – just cannot comprehend the problem.

Leave voters were not ignoring the experts. They were not stupid and misled. To claim that they were simply reinforces the underlying prejudices. Polls the weekend after the vote showed little remorse over voting decisions. They understood as well as anyone that the claims on both sides were more rhetoric than fact. They understood that change is a risk, but they also believed that they had little to lose. The experts, however, were not listening to them, and were too quick to denounce anyone who challenged their consensus. For the most part the experts are still not listening, and still denouncing.

The period between the UK referendum and the beginning of any formal negotiation on Britain’s European future provides a valuable opportunity for reflection and reform. Political leaders in the EU and the UK must think carefully about the substantive reforms that will be needed to address widespread social division and discontent. As long as people feel that they have no influence over the immediate circumstances within which they live, then divisions will become ever more entrenched and inflammatory. If more people feel in control of their lives then the problems within the UK and Europe can start to be tackled.

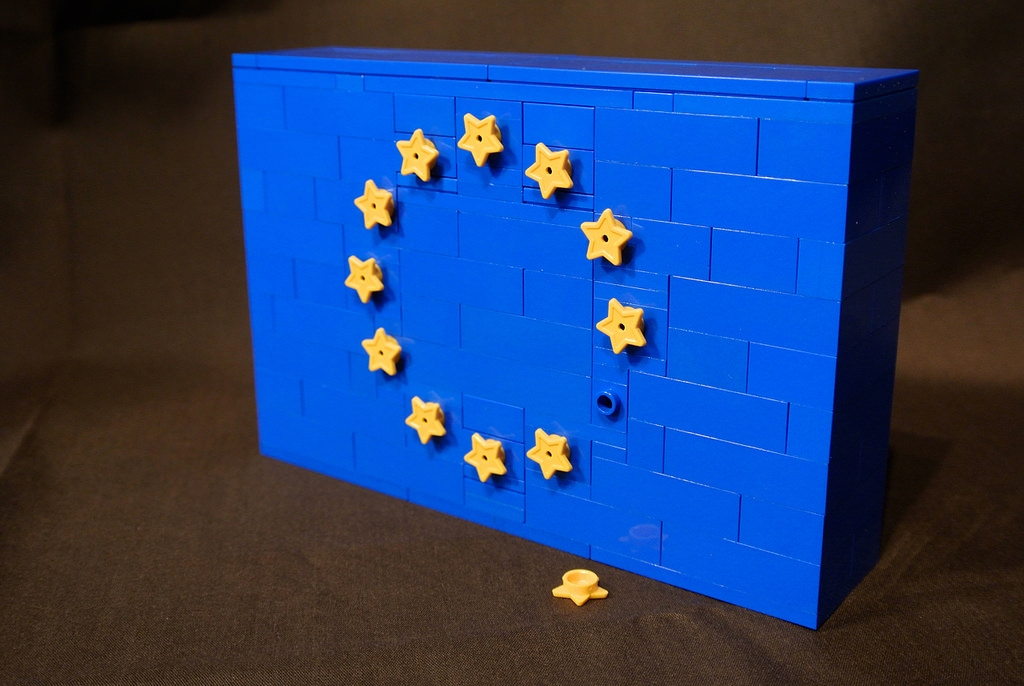

This article first appeared on the British Politics and Policy blog and it represents the views of the author, not those of the LSE Brexit blog or the LSE. Image credit: Paul Toxopeus CC BY-NC-S

Tony Hockley is Director of the Policy Analysis Centre. He was previously a Special Adviser to Cabinet ministers in the Conservative Government led by John Major, Adviser to Dr David Owen as Leader of the Social Democratic Party, and Head of Research at the Social Market Foundation. He has also worked in industry on public policy in London, Washington and Brussels. Since 2001 he has taught in the LSE Department of Social Policy, most recently in Behavioural Public Policy.

Your assessment of the situation is on point. Its a shame that the closed minds of those in power failed to do their homework, dis-jointment of local and central government reviewing meaningless stats instead of observing society as a whole (the role of the Councils is too plan & design environments). A lot of people have emigrated out of UK to Australia, NZ, Canada, US, Asia, Western Europe because of jobs but also because the landscape changing. UK has always welcomed high-skilled people from around the world because of their economic value & skills. When Greece, France & Italy was facing economic slowdown they we did not see a influx of 0000’s of people moving to UK!

It is not by chance that the areas that voted out are the most densely populated areas in UK. Large influx of immigrants from (1990 – 2011 ‘india, pakistan, africa’, and then in 2004 – 2015 ‘eastern europe’). As well as a lot of commonwealth people in skilled-jobs left UK because of visa restrictions in 2011.

Where the population of immigrants from asian, african etc. were in semi/low-skilled jobs they have been replaced with east europeans but on a much bigger scale than expected. This is a growing, repeat pattern of change that is the problem. More people classed as low-skilled or people looking for work can move with their families to the UK as cheaper labour (benefitting UK based businesses) but impacting towns, in the end the long-term taxpayers are subsidising businesses because they are putting their profits over people, they employ cheaper labour from eastern europe (who don’t necessarily pay taxes, and often have to claim a level of benefits to supplement their incomes), so long-term taxpayers are paying the price. You’re not going to see 000’s of UK people heading off to live in a low-GDP east european country, freedom of movement seems to only benefits low-wage workers from european countries and businesses!

Conservatives over-turned Labours immigration policies and replaced one grouping (controlled by visas) with another grouping (no controls), the impact of this is on the people born in Britain, public services & resources, jobs, pensions.

And as you rightly pointed out the changes in Southampton, was happening elsewhere. Southampton is mirrored replication in other areas in UK which came to light during the lead-up to the referendum campaign phase, Labour MPs admitted it was a wake-up call. Leave voters were not mislead they were discontented with the changing landscape of UK, prosperous areas and areas with industry decline becoming overpopulated, down-trodden, and run-down. London most diverse with immigration (wealthier europeans are central), yet further (west and east of London) the more compact and poorer the area is with majority immigrant populations from countries with lowest standard of living the more segregated the area. The thing is these areas was once the areas people in London wanted to move out to and now avoid because of the pockets of poverty in the last 20 years

UK is facing a crisis, I think a lot of western european countries are in the similar situation. Perhaps we need to take what we know now, all our medical, technological advancement and step back in time to when it was working and move forward from there because where we are now is not good.

Sorry but this is nonsense, not least bed as the demographic data on which it is based comes from the same source as the discredited polls forecasting a ‘remain’ win. How does Lord Wolfson fit into your blanket assessment, or James Dyson, Lord Lawson to say nothing of Boris, Leasom or Gove. I think far from many people not knowing anyone who voted Leave, they know quite a few, who chose not to tell them

This is nonsense.

You visited Southampton, good for you. I live in Southampton, and the only people who have a problem with the immigration here tend to be unabashed racists.

Frankly, racial harmony is Southampton is much better than it was when we had racial pockets as marked as we had with St Mary’s. In the 90s I was attacked outside Aggie Grays by 10 Sikhs walking home from a nightclub. It wasn’t unusual. There were regular racial clashes between the white and the Asian communities going back years.

Those days are gone. We still get the occasional racist attack, but we don’t get the same constant needle, or the regular friction. We don’t have gangs going out looking for trouble any more.

In that sense, racial harmony has never been better. Or, at least, it is for anyone who doesn’t have a short memory.

As for “Leave voters were not ignoring the experts. They were not stupid and misled. To claim that they were simply reinforces the underlying prejudices”

In which case, why do we have ignorant things asserted by Brexit supporters every day. Be it from the Brexit press. The Brexit politicians. Or just the standard Brexit voter?

I’m afraid, the tag that the Brexit supporters were stupid doesn’t come from prejudice, but from fair assessment.

It would be nice if the Brexit supporters who are actually intelligent didn’t suddenly espouse a conspiracy theory as if it were fact. Unfortunately, a lack of ability to do so only points to the fact their ideology is short cutting their rationality.

If you want any more proof that the Brexit supporters were stupid, look at that statement “They understood that change is a risk, but they also believed that they had little to lose”.

They understood they had little to lose? That is the single most ignorant thing they could think. Try going to a country where people eat rats to live, or where there is still types of slavery. “Nothing to lose”?

Those people who thought they had, as you said “nothing to lose”, have absolutely no understanding of the advantages of Western society they have been afforded, and why people risk their lives to just try and have as much to lose as those people who thought they had nothing to lose.

I’m not sure if this attitude is going to attract Leavers to vote Remain in any possible future referendum!!!

Patronising nonsense