Can a spatial model help us to understand the complexity and difficulty of the Brexit negotiations from Britain’s point of view? Chris Hanretty maps the possible outcomes and goes on to explain their limitations – namely timing (the two-year deadline once Article 50 is triggered), texture (the possibility of compromise) and bargaining power.

I’ve previously argued that Brexit negotiations will be more difficult than many in the UK realise.

When I argued that, I relied implicitly on spatial models of politics.

Spatial models of politics allow us to capture different features of the negotiations in a parsimonious way. They also allow us to represent actors as having very different positions on key dimensions. They allow us to capture the reversion point — the WTO terms upon which we’ll have to fall back if there is no deal (cf. BATNA; note WTO terms may not be a suitable reversion point).

However, it’s possible they ignore certain features of the negotiation which can’t be abstracted away: timing, texture, and power. To show that, I’ll need to sketch out the space of Brexit negotiations.

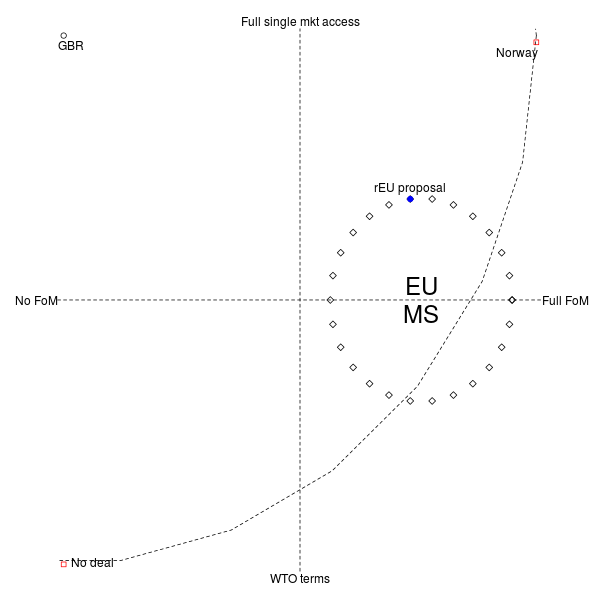

I’m going to posit two dimensions to the negotiations: a freedom of movement dimension, and a single market access dimension.

The poles of these dimensions are relatively clear:

- at one end of the freedom of movement dimension, you have current levels of freedom of movement; at the other end, you have no greater freedom of movement than that which exists between the UK and other third countries.

- at one end of the single market access dimension, you have current levels of access; at the other end, you have the panoply of tariff- and non-tariff barriers found in the WTO option.

Representing in two dimensions ignores lots of other things, such as the scale of future UK contributions to the EU budget, or to EU-run programmes. But some kind of simplification is necessary to get anywhere.

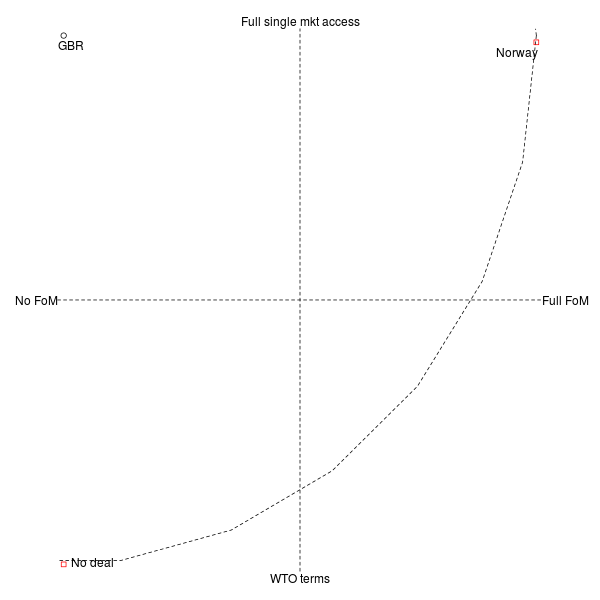

If we accept this as a reasonable representation of the space of the negotiations, we can place the UK in the top left corner. This combination of full single market access and no freedom of movement is the UK’s ideal outcome. You might call it the having-your-cake-and-eating-it point.

Points in the space which are equally far from this ideal point are equally (un)palatable to the UK. Points equally far from this ideal point can be joined by an indifference curve. I’ve drawn one such indifference curve in the plot.

We can add other positions to this plot. In the bottom left corner, we can place the reversion point: the situation we would behind if no deal of any kind was agreed, and the UK exited the EU on “WTO terms”. In the top right corner, we can place EEA membership, or the “Norway” solution.

I’ve represented both of these points as equally far from the UK’s preferred position. That implies that if it came down just to these two options, the UK would be indifferent between WTO terms and EEA membership. You may not agree with that characterisation:

- If you believe that the UK would clearly prefer the Norway option, then you should make the market access dimension longer, and the WTO option further away from the UK’s ideal point.

- If you believe that the UK would clearly prefer the WTO option,then you should make the freedom of movement dimension broader.

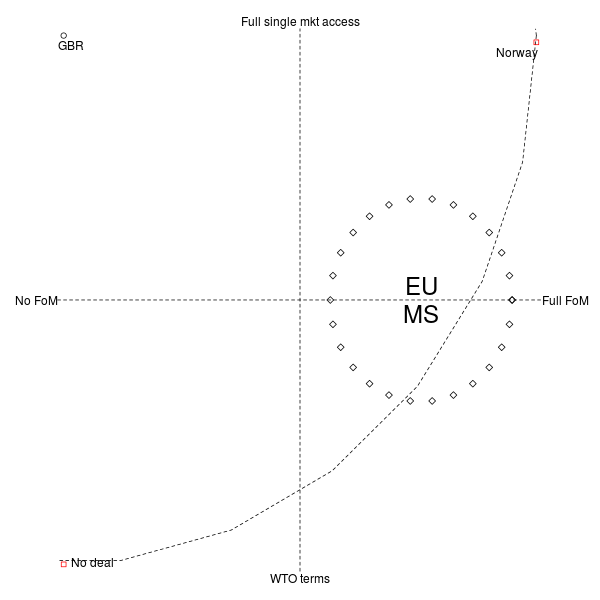

It’s far trickier to characterise the preferences of EU member states. For the moment, I’ll assume that some EU member states are willing to give the UK a deal which the UK prefers to either the Norway or WTO options (that is, they are inside the indifference curve), but that some member states are not willing.

With these kinds of preferences, a lot depends on control of the agenda. Suppose that negotiation took the form of a single proposal made by the UK, which other member states voted on, and which would only pass under unanimity. (I talk about unanimity because although any Article 50 deal requires a qualified majority, as I understand it any trade deal including services would require unanimity, and unanimity further simplifies things). In that case, the UK would make a proposal which is marginally closer to all EU member states than the WTO option.

Since other EU member states would prefer this option (it is closer to their ideal point, for all member states, including the awkward one marked), they would accept.

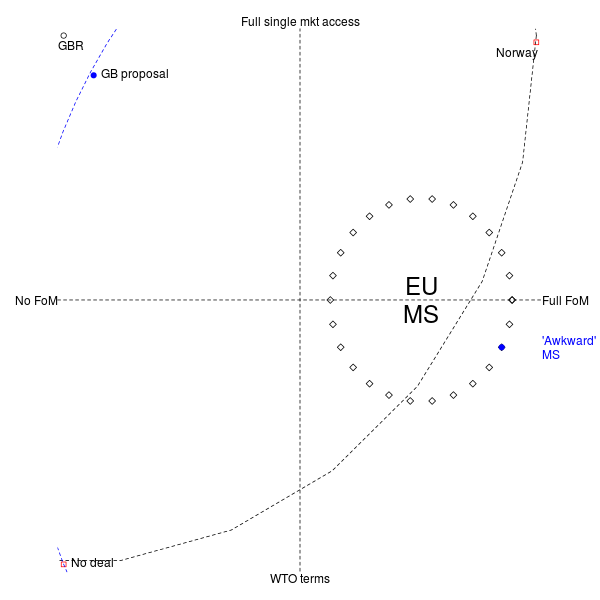

The problem (for the UK) is that the UK will not be making a single take-it-or-leave-it offer. If negotiation takes the form of a single proposal made by a randomly chosen EU member state, the outcome looks very different. (See the blue dot below). If the member state is within the UK’s indifference curve, it will make a proposal at its own ideal point. If the member state is outside the UK’s indifference curve, it will make a proposal at the closest point on the UK’s indifference curve.

In practice, negotiations will take the form of multiple proposals which will never be formally voted upon, but which must nevertheless result in a final vote within two years.

My first concern is about how to model the impact of that phenomenally imposing two year deadline. One way is to say that the UK and rEU 27 alternate in making proposals, but that the rEU 27 can “run out the clock” in order to make sure that their proposal is the last proposal considered before the deadline bites.

This suggests that the impact of the two-year deadline is just to ensure that the rEU27 retain agenda control. This implies three things:

- the identity of the proposer in the final “round” of negotiations will be important (i.e., what are the ideal points of the Commission appointed negotiator, and of the countries which will be chairing the Council at that time [Romania; Austria])

- the eventual outcome will be within the convex hull of member states’ ideal points;

- (if preferences are broadly as I have characterised them) the eventual outcome will be far closer to the average EU member state ideal position than the UK’s ideal position

but still, this seems like a pretty weak interpretation of the force of the two-year deadline.

My second concern is about the texture of the space I’ve just depicted. It’s fairly easy to place the Norway and WTO options, but it’s harder to position compromise solutions.

The attitude of the EU is that the freedoms afforded by EEA membership are “four and indivisible”, and that consequently the interior of this space is void. There are a number of ways of dealing with these kinds of statements:

- You can interpret these statements as signalling preferences, so that rEU MS really would want the UK to be worse off than either Norway or WTO.

- Or you can treat it as a statement about policy: that although we like to represent choices in an infinitely divisible policy space, you can’t pick and choose, just in the same way that you can pick and choose which pages of a book you want to buy.

I certainly worry that the UK civil service will treat these statements as just cheap talk. I think that it was the failure of the Conservative government to take seriously the commitment to freedom of movement amongst other EU member states that led to the February negotiations being so disappointing. (You’ll sometimes hear this argued in a different way: Merkel could have kept Britain in by conceding on freedom of movement. One person’s principled politician is another’s dangerous intransigent).

My third concern is about power. Studies of EU decision-making tend to suggest that whilst spatial models of decision-making do reasonably well, bargaining power matters. Intuitively, I think having to negotiate

- with a group of countries that are collectively larger than you;

- who decide by QMV or unanimity;

- in a two-year timetable;

- where the reversion point is particularly unpalatable

is a difficult ask, and means that the UK has limited bargaining power. But it’s difficult to specify how bargaining power matters ex ante. The existing measures of bargaining power have been developed to explain decision-making within the EU, but the present situation is so unusual that those same considerations may not play out in quite the same way.

Some of these concerns may be exaggerated. I imagine there are game theorists out there who will be able to suggest a role for time which is independent of the last-period proposer effect I’ve described above. Equally, I’m sure that over time discrete bundles of proposals will emerge, and we’ll all have shorthand ways of referring to them (“the January text”; the Verhofstadt counteroffer). I don’t know whether anyone intends to replicate for Brexit the mammoth work carried out by the DEU project and other successor projects (see here and here), but if they do, they’ve got their work cut out for them.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It was first published on Medium.

Chris Hanretty is Reader in Politics at the University of East Anglia.