In the fourth of LSE’s Continental Breakfasts – held under Chatham House rules, so participants can speak as freely as they wish – a roundtable discussed the future of Britain’s trade outside the Single Market. Chrysa Papalexatou reports on some of the key points.

In the fourth of LSE’s Continental Breakfasts – held under Chatham House rules, so participants can speak as freely as they wish – a roundtable discussed the future of Britain’s trade outside the Single Market. Chrysa Papalexatou reports on some of the key points.

The UK’s preferred Brexit outcome remains unclear – at least in any depth. The General Election result has only added to the confusion. But having not negotiated any trade agreements since joining the EU in 1973, the UK will find itself in the position of having to sign 295 trade deals just to maintain its current trading relationships. If cross-Channel trade falls, it will need to find new trading partners to make up the difference.

International trade today

Much of the discussions on post-Brexit trade have focussed on tariffs, which is to ignore the nature of today’s international trade system. As Matthew L Bishop (2017) suggests, it seems some politicians believe trade is all about finished goods going back and forth between countries. According to UNCTAD (2013) 80% of trade takes place in ‘value chains’ linked to transnational corporations. Most international trade is not shaped by the multilateral agreements on tariffs, but by preferential trade agreements between the biggest markets (EU, US, China and Japan) which aim at reducing costs related to non-tariff barriers (Steve Woolcock, 2015).

So contemporary trade negotiations have little to do with freeing trade in the classical sense of the word. The challenging purpose of a trade agreement today is rather to reduce these non-tariff related costs – while ensuring that legitimate public policy objectives pursued through regulation are safeguarded. In other words, the content of trade negotiations and agreements today is as much, if not more, about rules that facilitate trade and investment by reducing regulatory incompatibility and duplication.

It is in this sense that the EU Single Market needs to be understood. It is the most advanced form of rules that ensure such a balance between commercial, social, environmental and other legitimate policy objectives. Rather than restricting trade, EU rules facilitate trade and investment.

In leaving the EU, UK policymakers must define what new balance between commercial and social/environmental policy objectives is in the national interest. In today’s trading system, as production and investment undergo further globalisation and ecommerce gives smaller companies access to the international arena, this implies that for companies to be competitive in international markets, trade costs related to non-tariffs are, and will continue to be, of major relevance (Steve Woolcock, 2015). These costs are often related to meeting the regulatory standards in the export markets. The more different these standards are, both from each other and from the domestic standards, the more expensive it is to comply.

Trade agreements therefore include provisions on ‘regulatory equivalence’ which set certain regulatory parameters that constrain domestic policy. Trade then tends to flow more freely among groups of countries with similar regulatory standards, who may find it easier to reach agreement. Multilateral negotiations generally try to strike a balance between reducing these non-tariff barriers and leaving room for national governments to pursue their own legitimate domestic public policy.

Outside the single market and the customs union, some immediate costs of doing business with the EU will emerge, such as the costs of border controls (i.e. customs clearance, border checks, rules of origin costs). Companies based in the UK will not have guaranteed access to EU (or other) markets and could face high costs related to non-tariff barriers. One of the main reasons that the UK has been attractive to foreign companies is that it acts as an export platform to the rest of the EU. Leaving means that this position is under threat. This matters because foreign multinationals tend to be highly-productive firms and they bring new technologies and management skills with them (Bloom et al, 2012). At the same time, globalised networks allow companies to relocate their activity or investment quite easily, and market access can therefore be the driving factor in where firms choose to locate production.

Outside the EU, the UK will no longer be part of the group which currently plays a major role in shaping these international rules, and will have to follow rules set by the EU and other major economies in order for UK-based companies to compete in the global economy. More simply, the UK is facing the danger of becoming a “rule taker” rather than a “rule maker” in the international trade arena (Steve Woolcock, 2015). Even were the UK to maintain full access to the single market, it would be in a similar position to Switzerland, whose exports have to obey EU regulations, but does not have a seat at the table when those regulations are decided (Swati Dhingra and Thomas Sampson, 2015).

In order for UK exports to continue to meet the standards that are required for access to these foreign markets, the UK will have to either remain within the jurisdiction, or duplicate the work of no fewer than 34 European regulators, covering areas such as agriculture, energy, transport and communications. There are already growing concerns from many industries about how to avoid a “cliff edge” scenario where companies are unsure what or how regulation applies to them (CBI, 2017).

If the UK signs new trade agreements with trading partners with lighter regulatory standards, then companies may not be able to use components from these countries in goods they export to the EU. Also, if the UK maintains regulatory standards that are more costly than those of their new trading partners, then UK producers may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

The UK and its trading partners

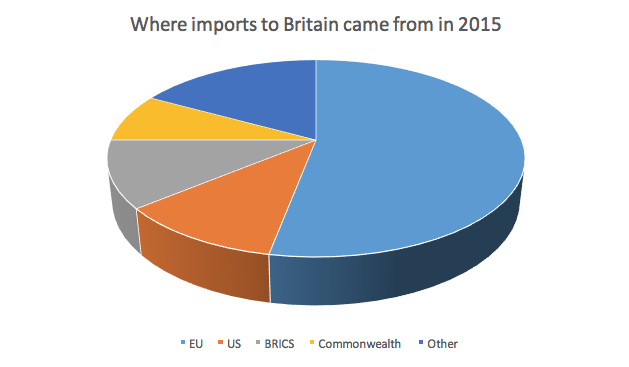

In 2015, the 50 countries with which the EU currently has FTAs accounted for 13% of the UK’s trade. This rises to 25% when including countries with which the EU is currently negotiating (excluding the US).

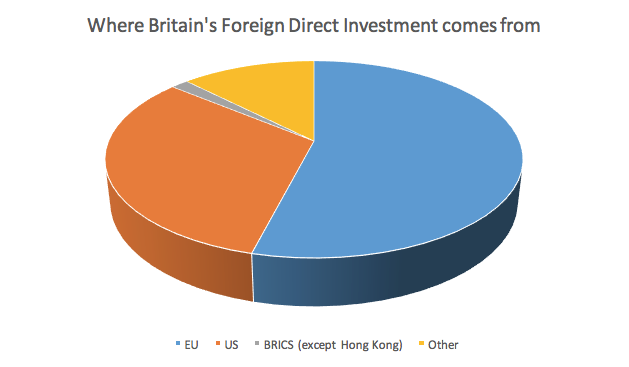

Of the outward FDI, 43% goes to the EU, 23% to the US and 5% to the BRICS.

While these ratios are likely to change over time, especially after Brexit, they indicate that the EU and US together account for over 60% of UK’s export market and constitute the core of the UK’S trading relationships.

The UK has more trade outside the EU than other EU countries, and so may be better placed to adjust to leaving the bloc than other member states would be. However, even in the most optimistic scenarios, it would be a very long time before trading relationships with the Commonwealth or the BRICS could offset a significant reduction in UK trade with the EU. Furthermore, many of these countries – 32 members of the Commonwealth – already have trade agreements with the EU, so unless new agreements are quickly organised, then the UK could find itself with less favourable trading terms with those countries than before it left the EU.

Thomas Sampson (2017) argues that the purpose of trade agreements is to make all parties better off: governments agree to refrain from adopting ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies which benefit their own economy only because they hurt other states. Trade negotiations are not about countries identifying a common objective and working together to achieve it: they are a bargain between countries with competing objectives.

One of the Brexit campaign’s main arguments was that the UK has the ability to negotiate its own trade agreements more quickly than the EU. It is true that small countries such as the EFTA countries can negotiate agreements more quickly than the EU: however, this is usually at the expense of a good agreement, since very unequal negotiations tend to be over quickly and have unequal outcomes. Bargaining power affects the outcome of trade negotiations. The statistics above clearly indicate that the UK starts from a weaker position than the EU, since EU-UK trade accounts for a much larger share of the UK’s economy. At the same time, a major EU priority would be to preserve the unity of the EU27, ensuring that the UK does not gain from leaving by freeriding on the benefits of trade without contributing to the costs that make the Single Market work, or undermining EU regulatory standards.

The Government’s Brexit white paper mentions sectoral agreements, and there are obvious sectors that are at the top of the list, such as financial services or automotive exports. Nonetheless, this approach may be problematic, both because the EU may resist it and because of the complex level of interconnectedness among sectors. In the service sector, financial services are most at risk. Concerns have also been expressed about construction, where depreciation of sterling – which may help exporters in the manufacturing sector – could increase the cost of building materials.

Brexit campaigners suggest the UK will not face substantially higher trade barriers after leaving the single market. The EU is considered to have a relatively liberal trade regime with low external tariffs. Even if the UK faces additional barriers – such as new customs requirements and certificates of origin – the costs could still be relatively small. Gros (2016) argues that Switzerland – which is even more integrated into EU production chains than the UK – shows that efficient customs administrations on both sides are enough to keep such barriers to a minimum.

Trade with the US

According to the Office for National Statistics., the UK runs an overall trade surplus with the US of about £14bn annually, exporting mainly pharmaceuticals and cars. Since President Donald Trump considers the reduction of US trade deficits a priority, a good deal for the UK would seem to pose a challenge. However, according to the US Department of Commerce, the UK in fact has a trade deficit with the States.

In any case, a US-UK deal will only be possible when the UK leaves the EU and has its own external trade policy, which is supposed to be by the end of March 2019. US negotiators would want to know what kind of a trading relationship the UK will have with the EU, making a quick and easy US-UK trade deal unlikely. The UK priority will not be tariff reduction but improved market access for services and investment, as well as enhanced mutual recognition of standards, qualifications and regulations. But given the UK is the smaller market and the weaker party, the US may ask a lot – for example, business opportunities for US companies in the NHS, access to British food and animal feed market for GM-growing US farmers – and give little.

Other trade deals

Another priority should be new deals with countries with which the EU already has an FTA. However, it is not clear whether these countries will be willing to replicate the terms of the EU FTA: they might expect to get a better deal with the UK than the one they managed to negotiate with the EU. Simon Hix and Hae-Won Jun (2017) have suggested that Seoul might feel it could improve on the terms of the EU-South Korea agreement (given that the EU has an economy 10 times larger than South Korea). The fact that the UK may be impatient to conclude such deals may also put it at a disadvantage.

A main argument of the “liberal leavers” in the Brexit campaign was that EU membership constrains the UK’s ability to expand its trade links with the rest of the world – notably China and India, but also with the Commonwealth (Murray-Evans, 2016). In the last few decades the UK has seen its exports to non-EU countries growing faster than those within the EU (Lea, 2016). Nonetheless, new opportunities may take a long time. For example, it took Australia ten years to agree an FTA with China and India, and six years to get a deal with ASEAN.

Do people who voted for Brexit want more globalisation, anyway?

Even if the UK were able to achieve the best possible deals, would domestic political constraints allow it?

Attitudes towards free trade are changing – not in countries that have been traditionally protectionist, but those that embraced globalisation. Trade liberalisation is no longer the engine of global growth that it was before the financial crisis. The rise of xenophobic sentiment and the cooling of public opinion towards free trade has stimulated academic and political debate. Some social groups or geographic areas are worse off as a result of globalisation, and this may have influenced their voting behaviour. Colantone and Stanig (2016) suggest that globalisation, and in particular the Chinese import shock, was a key driver of the Brexit vote.

According to Jeffrey Sachs (2016), Brexit reflects a widespread phenomenon in the advanced world – rising support for populist parties campaigning for a clampdown on immigration:

“Roughly half the population in Europe and the United States, generally working-class voters, believes that immigration is out of control, posing a threat to public order and cultural norms.”

As Gros underlined, many Brexit voters clearly wanted to impose controls on the movement of workers from the rest of the EU without losing access to the single market. Many leaders of the Leave campaign were promising this kind of deal prior to the referendum. What appears clear is that access to the single market is linked to free movement of people. There seems to be a contradiction in what many see as the motivations for the vote to leave the EU and Leave campaign claims that Brexit will make the UK more open.

The UK has been a rhetorical advocate of free trade – but as a member of the EU, it has not had to make political decisions about which sectors of the economy to prioritise in its trade policy, and by implication, which geographical regions. National politicians will now have to take responsibility for them.

Moreover, without being able to advocate through the EU, will the UK have less influence over the international trading system, which seems to be retreating from the rules-based multilateral agenda on which the UK outside the EU would rely?

References

Oxford Economics (2016) Assessing the economic implications of Brexit.

Bloom, N, R Sadun and J Van Reenen (2012) ‘Americans Do I.T Better: US Multinationals and the Productivity Miracle’, American Economic Review 102(1): 167-201.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Chrysa Papalexatou is a research student at the LSE’s European Institute, specialising in EMU and economic inequality.

2 Comments