While the public have voted to leave the EU, it is less clear what that means in terms of policies around key aspects of EU membership. Sara Hobolt and Thomas Leeper (LSE) examined public opinion on various dimensions of Brexit using an innovative technique for revealing preferences that asks survey respondents to evaluate bundles of negotiation outcomes. Their results suggest that while the public is largely indifferent about many aspects of the negotiations, Leave and Remain voters are divided on several key issues.

While the public have voted to leave the EU, it is less clear what that means in terms of policies around key aspects of EU membership. Sara Hobolt and Thomas Leeper (LSE) examined public opinion on various dimensions of Brexit using an innovative technique for revealing preferences that asks survey respondents to evaluate bundles of negotiation outcomes. Their results suggest that while the public is largely indifferent about many aspects of the negotiations, Leave and Remain voters are divided on several key issues.

What did we do?

Measuring public preferences is commonly approached through survey questionnaires, in which individuals express a degree of favour or disfavour toward a particular object such as a policy, product, political candidate, or – recently – possible outcomes of Brexit negotiations. When objects of evaluation have many features, such as preferences over trade, preferences over immigration, etc. entangled in current negotiations, it is common to ask about those specific aspects as separate questions. Evaluating the relative importance of the different features, however, becomes empirically challenging.

An alternative approach is “conjoint” experiments, in which respondents are asked to consider “bundles” of outcomes as a whole – that is, to consider a possible Brexit negotiation deal that includes a large number of different features as a complete package, with the specific features (e.g., the amount of immigration control) randomly varied. We recently conducted a conjoint experiment about the public’s attitudes toward Brexit with a total sample size of 3,293 respondents. It was fielded 26-27 April via YouGov’s online Omnibus panel.

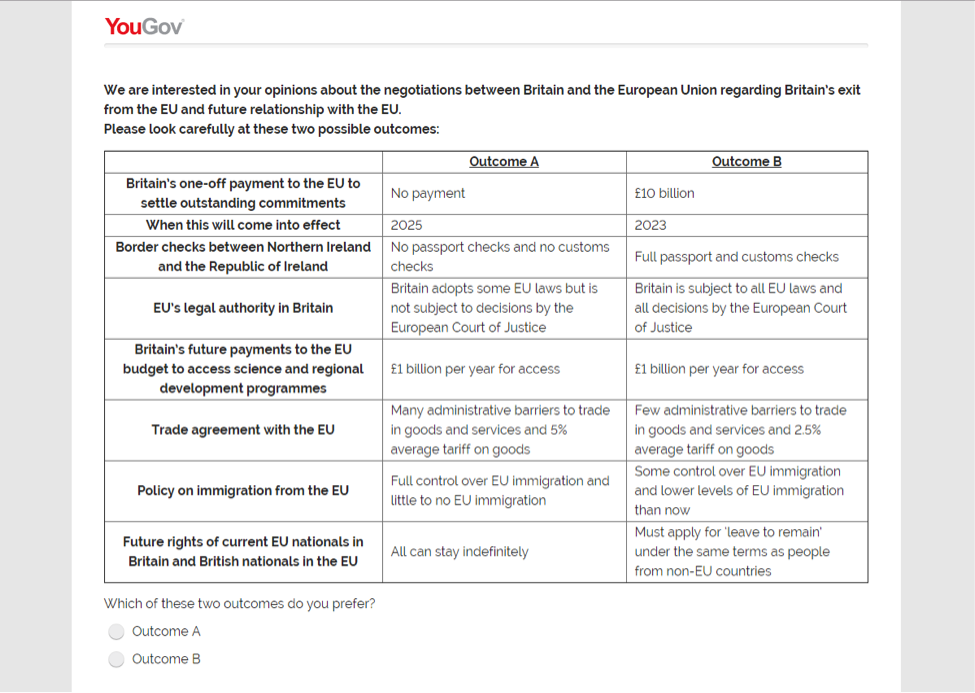

In our design, respondents were shown a series of possible Brexit negotiation outcomes in pairs and were asked to choose which one of the two that they liked best (there was no “don’t know” option). This requirement that they choose – that they make trade-offs between the different aspects of the negotiations – is crucial to the conjoint approach and to our results. A screenshot of what the respondents saw is below:

Conjoint experiments differ considerably from traditional public opinion surveys in a number of ways that make powerful tools for understanding preferences. First, they allow us to make comparisons between respondents’ evaluations of different bundles in order to detect the relative importance of individual features. Rather than asking respondents directly about each separate feature, we can allow their choices in these difficult trade-off scenarios to reveal the acceptability of different features. Our results, therefore, have to be understood as the preferences respondents hold over Brexit when all of the features of the negotiation are weighed together as a package. While this makes it difficult to compare our results to those of more traditional polling, we gain a considerable amount by asking respondents to engage directly with the difficult trade-offs involved in the negotiations.

Second, because the features that are shown to respondents are fully randomized in the design, we ensure that respondents do not infer or attempt to infer how different aspects of negotiations might be tied to others. For example, if we simply asked respondents about their preferences over trade policy, they are likely to make assumptions about what that might mean for immigration policy. In the conjoint, we provide information about both aspects (as well as others), thereby making any trade-off explicit rather than implicit. As well, in our design, we never use any of the most politicized labels from ongoing debate – such as “hard” or “soft” Brexit, or “freedom of movement”, “free trade”, etc. – but instead attempt to use more precise language to describe features of a possible deal.

Third, because each respondent is shown multiple pairs of trade-offs (six in our design), a conjoint design yields a very large dataset of revealed preferences, in our case just shy of 20,000 data points about what the public wants from Brexit. This gives us considerable statistical power to detect differences in Leave and Remain voters’ taste for various components of negotiations. The fact that the packages of negotiation outcomes shown to respondents consist of fully randomized combinations of features means that we can use straightforward mathematical (albeit perhaps confusing at first glance) procedures to measure those preferences.

Finally, a conjoint experiment allows us to present our results in two distinct ways. One of these describes the pattern of preferences in terms of levels and the other describes the pattern of preferences in terms of effects. Because respondents are forced to choose one of the two outcomes shown in each pair, we can draw out of the pattern of choices the proportions of respondents that would accept or reject outcomes containing a given feature (in light of the trade-offs between features and the strengths and weaknesses of the chosen negotiation bundle as a whole).

On this measure of levels, a feature scoring 100% means that respondents would always choose outcomes that included that feature, regardless of any other aspect of Brexit. For example, if the immigration policy “Full control over EU immigration and little to no EU immigration” scored 100%, the public would trade-off everything else to have that immigration policy in a bundle consisting of any other combination of features. If it instead scored 0%, it would mean the public would never accept this policy and would similarly trade-off everything else to avoid it. If, finally, it scored 50% that would mean that the public was largely indifferent – they would accept it 50% of the time and reject it 50% in light of other possible features of the negotiation. These are not unconstrained preferences as in typical polling, but instead patterns of opinions reflecting the inherent complexity of the decisions at hand. In other words, if forced to choose (and to choose possibly between unpleasant alternatives), what percentage of the public would accept or reject whole deals based on this particular feature?

The second way of presenting the results is as effects – in the statistical language of a conjoint design, an “average marginal component effect”. In this presentation, rather than highlighting rejection versus indifference versus support, we can convey the degree to which a given feature increases or decreases support for a bundle as a whole relative to a baseline deal. The meaning of the results are identical but are presented in a way that cannot be interpreted as percentages of the public that support a feature or a bundle of features. Instead, they are weightings of the importance of different features relative to a baseline combination of features – in our case, we treat a “no deal” exit of the EU as the baseline condition, so a positive effect can be interpreted as a given feature increasing support for a negotiation outcome that contains it and a negative effect can be interpreted as a given feature decreasing support for a negotiation outcome that contains it.

The Specific Survey Procedures

Our design followed the emerging paradigm for conjoint studies, entailing a number of features of Brexit negotiation outcomes, and the request that survey participants complete multiple discrete choice tasks. At the beginning of the study, participants completed a few brief background questions, with most demographic data being drawn from YouGov’s profile variables, and then completed five sequential conjoint profile ratings. Each conjoint task presented two alternative Brexit negotiation outcome scenarios (see figure above) and asked participants: “We are interested in your opinions about possible agreements between Britain and the EU regarding Britain’s exit from the EU and future relationship. Please consider the following two possible agreements.” They were then shown two outcomes that varied along eight dimensions. After that, they were asked “Which of these two outcomes do you prefer? (Outcome A; Outcome B)” and forced to choose one of the two.

The eight dimensions (attributes) were chosen to cover the most salient aspects of the Brexit negotiations. These features were: (1) immigration controls, (2) legal sovereignty, (3) rights of EU nationals, (4) ongoing EU budget payments, (5) one-off settlement, (6) trade terms, (7) status of the Republic of Ireland/Northern Ireland border, and (8) the timeline for Brexit. The levels were designed in such a way as to range between the two most extreme negotiation outcomes: a ‘ soft Brexit’ with continued British membership of the EU’s Single Market and Customs Union and a ‘ no deal’ scenario in which negotiations break down before an agreement has been reached.

The selection of levels of each feature for each profile was fully randomized, as was the order in which those features was presented in each table. This mitigates the risk of “profile ordering effects” wherein certain features are deemed more important because they are presented first or last in the table.

LSE Blogs image, licenced under Public Domain.

LSE Blogs image, licenced under Public Domain.

Our Results

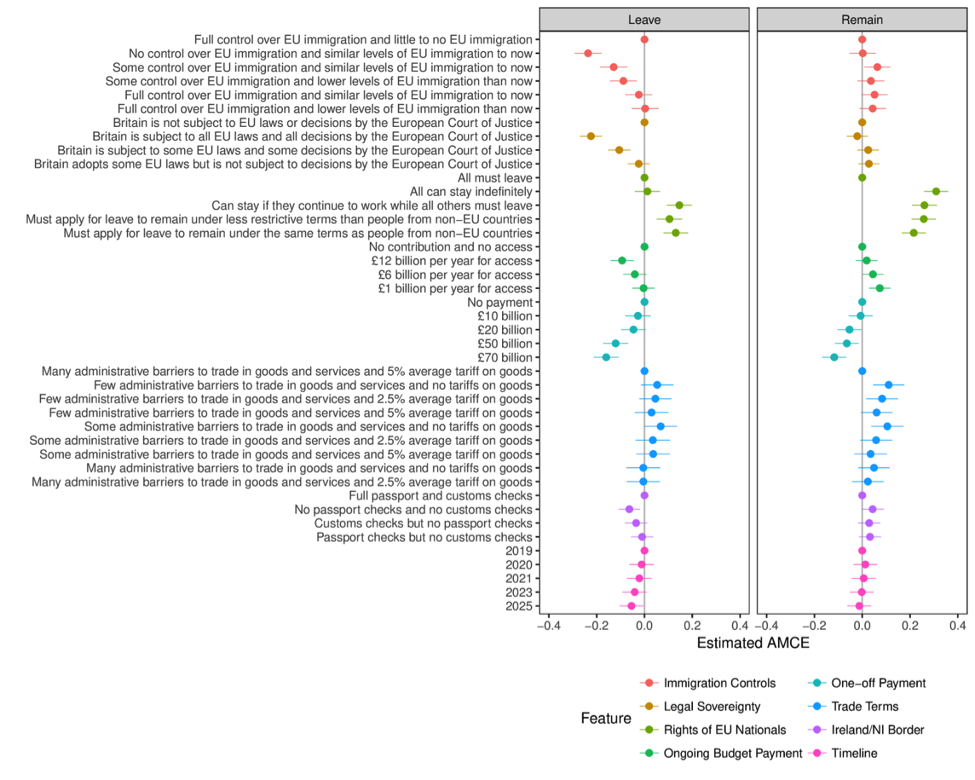

Starting with the presentation of effects, we express the effects against a baseline defined by the ‘no deal’ scenario in which Britain and the EU are unable to conclude an agreement on Britain’s exit. This means that there would be no trade deal, full legal independence of Britain from EU law and the European Court of Justice, no one-off or continuing payments to the EU budget, full control over immigration with no continuing EU immigration, the loss of rights of EU citizens currently residing in the UK, and a full (customs and passport) border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. Positive effects thus indicate support for ‘softer’ Brexit outcomes and negative values indicate opposition to those scenarios. The figure below presents these results separately for Leave and Remain voters, ignoring those who did not vote, based upon a measure of vote choice which was recorded immediately after the 2016 referendum. The lines around the point estimates are 95% confidence intervals.

Relative to the baseline of a ‘no deal’ exit, Remain voters favour alternative deals in every policy area except one-off payments to settle outstanding debts to the EU. They most favour a Brexit scenario that is ‘softer’ with respect to immigration, the rights of EU nationals, trade deals, ongoing budget contributions, and the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. Leave voters, by contrast, do not like any of these policy alternatives, except in areas related to the rights of EU nationals living in Britain and the nature of any trade deal. What people would like Brexit to mean therefore depends on how they voted in the referendum.

What people would like Brexit to mean depends on how they voted in the referendum

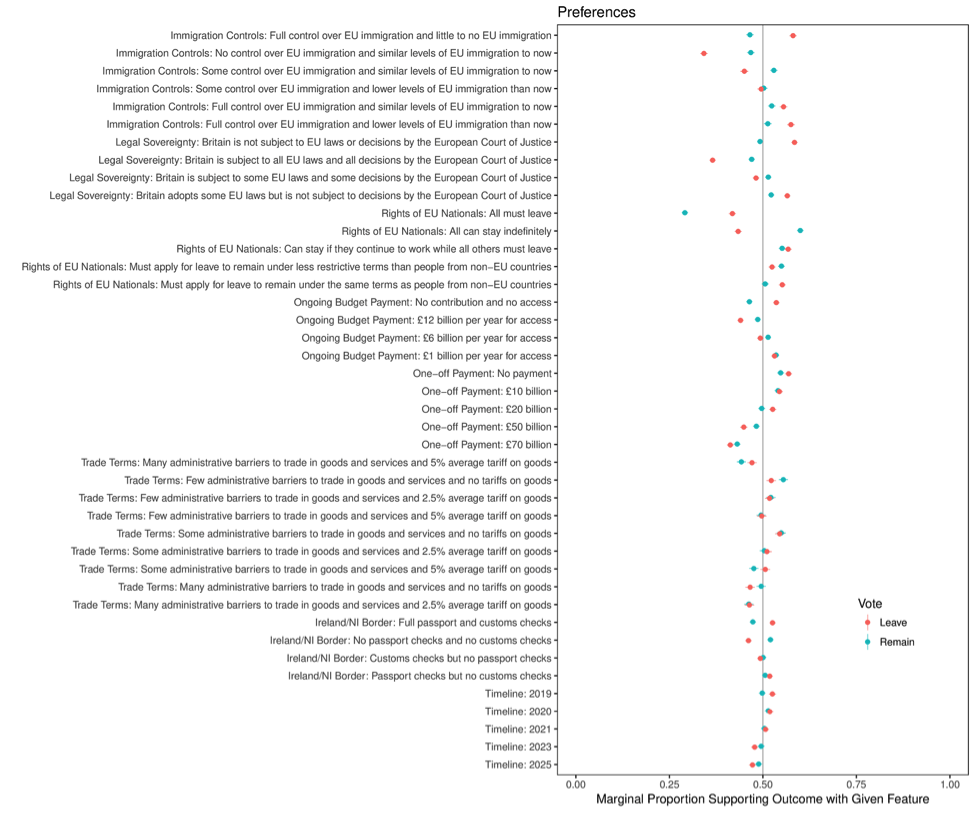

When we translate these results into levels, we obtain results that are mathematically identical to those above but that can be mapped out in terms of the proportions of respondents that would accept or reject outcomes that include each feature (see figure below). As should be immediately clear, most of the levels hover right around 0.5 (50%), meaning that respondents are largely indifferent about most of the aspects of the negotiations and the particularities of the deals. That said, there are some striking patterns of results (which will echo the effects analysis above).

Perhaps most striking is that few of the levels diverge particularly far from 0.5 (50%) toward either complete rejection (0%) or complete acceptance (100%). That means that for our respondents, most aspects of the negotiations are not sufficiently unacceptable to completely avoid at all costs nor are there aspects that are so important as to drive compromise of other features at all costs. The headline conclusions are therefore that the public is surprisingly willing to compromise on some aspects of the negotiations, even things that are arguably very important to them (as shown in the effects analysis above).

What we caution readers to avoid, however, is looking at these numbers as raw measures of support for particular features (as in conventional public opinion polling). This they are not. At no point did we ask respondent to evaluate individual features – they were only asked to make judgments of bundles of outcomes. The results we present are the preferences that are revealed by their choices between bundles. A value, for example, of 0.29 (29%) for Remain voters on “All must leave” does not mean – as it would in a typical polling context – that 29% of Remain voters favour all EU citizens having to leave to the UK. Instead, given the design of our study, it suggests that 71% of the time, Remain voters would reject negotiations that contained that policy feature regardless of everything else it was bundled with and accept it only 29% of the time in light of everything else it was bundled with. When Leave voters score at 0.58 (58%) on “Full control over EU immigration and little to no EU immigration” that does not mean 58% of the Leave voters want no EU immigration but rather than Leave voters will accept negotiation outcomes containing that policy feature 58% of the time and reject negotiation outcomes containing it 42% of the time.

These somewhat complex interpretations, which require looking at the whole of our results together (not just the individual levels of support for specific items) and considering precise what task was given to our survey respondents, reflects the complexity of the task of negotiating the UK’s exit from the EU. When tasked with make difficult decisions involving complex trade-offs, what is acceptable and what is not? The answers aren’t always easy and what we see consistently is that the public – both Leave and Remain voters – are willing to make trade-offs. Indeed, they appear to be almost completely indifferent over some aspects of the negotiations (such as the status of the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland and the timeline for agreeing any deal). It is not easy, as the government must now do, to make trade-offs between complex and interconnected aspects of Britain’s relationship to the EU. We designed our study to bring that complex decision-making to the public to measure their preferences in a new and different way from much other polling. Our results need to be read as a reflection of that complexity and the particular design we used.

Conclusion

While there appear to be few aspects of the negotiations that Leave and Remain voters demand at all cost or reject at all cost, there are aspects of the negotiations that are very important to them. Leave voters are particularly concerned about control over immigration and opposed to deals that give Britain less than “full control” over immigration. They are similarly concerned about legal sovereignty and any “divorce bill”. They also strongly prefer scenarios where EU citizens are able to apply for residence more than scenarios where all must leave. Remain voters care much more about the rights of EU citizens – indeed, no other aspect of the negotiations appears to matter more to them. They also agree with Leave voters that trade terms with fewer barriers and lower tariffs than a “no deal” scenario would bring are preferable to a hard break from the common market. Yet, ultimately, citizens are indifferent about many aspects of Brexit.

A detailed technical report is available containing all information about our study design and analysis.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Sara Hobolt is Sutherland Chair in European Institutions at the LSE European Institute.

Thomas Leeper is Associate Professor in Political Behaviour in the Department of Government at the LSE.

This analysis seems to assume that all outcomes are somehow neutral in terms of consequences outside the outcome of the preference itself.

e.g. Stating ‘all EU immigrants must leave’ as a preference surely must be presented with a consequence (such as a drop in tax receipts and therefore a drop in public services / increase in taxation / increase in public debt).

I want to leave aside the media outreach disaster caused by the pre-circulation of these results, that will be difficult now to ameliorate. (And incidentally I feel you have now a major responsibility to address the awful misunderstanding now doing the rounds across the British public)

Let me concentrate on one methodological aspect of the study. Where is the logic in including options that are not in fact available to negotiators, such as a zero exit bill, which is legally impossible even of there is no deal? Or indeed expulsion of all EU citizens which is not an option under international treaties? Including these as ‘options’ has a massive effect on public discourse, and on the political climate. But again leaving that aside, since these options are not really available, you are not actually generating genuine tradeoffs, and this necessarily affects the remaining results in the study. In a conjoint bundled methodology one has to be extremely careful not to bring in any unrealistic option since this has consequences down the road for preferences over every other option. Similarly not including outcomes that _are_realistic (e.g. no brexit at all) has knock down consequences for all the other options. Does this not vitiate your whole study?

You may find this interesting

“Huge New Study Reveals What The British Public Really Want From Brexit”

https://www.buzzfeed.com/jamesball/remain-and-leave-voters-are-surprisingly-united-on-backing?utm_term=.pxNBNAewb3#.ex2oeDOzx9

68 % want hard brexit

67% Prefer no deal

What degree of confidence do you have about the level of comprehension of the terms and expression used to describe the options?

How do you know that the subject have any understanding of “immigration control”, “leave to remain” “legal sovereignty”, “administrative barrier”, “£70 billion” and so on?

Can you prove that each respondent was able to define any of the phrases and use it in a practical example?

Aren’t you ignoring the real level of rational understanding of the sample?

What if each of these expressions and terms was simply associated to a biased lump of emotions?

How different would the result be?

Can you please publish the text of your request to The Independent to rectify headline and content of the piece by Jon Sharman?

The problem is that most of the UK electorate do not have time to study the details of EU/UK negotiations.

I would suggest that people tend to follow the lead of the party they instinctively vote for in general elections. On a UK level the big parties are the Conservatives, Labour, the Lib Dems, the SNP, UKIP, the DUP and Sinn Fein. These act as the filters by which most people try to understand what is going on.

It is up to the elected politicians in these parties to explain to their supporters what is going on, and not rely on “soundbites”.

Their record so far is not good. They had to be forced to hold a debate in parliament over Article 50 by the court case of Gina Miller. Who, outside secretive party inner circles, really knows what the negotiating stance of either the Conservatives or Labour currently is?

One of the outcomes you tested is the one in which any EU national who stopped working because of retirement, parenting at home or disability would lose the right to stay (the wording used is “can stay if they continue to work while all others must leave”).

I think this should be unacceptable in a civilised society yet both remain and leave voters show strong support for this option.

It seems that the narrative that immigrants should be accepted only if they provide a financial return has been effective.

.

One of the outcomes you tested is the one in which any EU national who stopped working because of retirement, parenting at home or disability would lose the right to stay (the wording used is “can stay if they continue to work while all others must leave”).

I think this should be unacceptable in a civilised society yet both remain and leave voters show strong support for this option.

It seems that the narrative that immigrants should be accepted only if they provide a financial return has been effective.

BUT

The whole of your thesis hangs on the choice of questions YOU invented.

The choices may or may not be realistic in terms of the negotiations and in terms of what people want from the negotiations.

The survey includes the option, as quoted in the article, “Rights of EU nationals: All must leave”. Queries: doesn’t including this as a possible option normalize the fantasy of mass-deportation? Is that an ethically responsible way to conduct an academic survey? Is it right that respondents should be invited to consider it possible and reasonable to choose to ask the government to do something that is illegal under international law, just as they might choose a picnic bundle that happens to include tea rather than coffee?

Here is an important response to the media coverage generated by this survey, by Helen De Cruz and Mauricio Suarez: https://medium.com/@helenldecruz/when-mass-deportation-becomes-an-ordinary-survey-question-d97254f294d7

This is an interesting, but very difficult report to make sense of. A pity the confusing headlines got out before the report itself.

Am I right in thinking that it shows that:

– leavers feel more strongly about the things they care about than remainers feel about the things they care about

– although politicians and the media think that people care about specific policies of the kind you have investigated, mostly people have no strong views about the specifics of Brexit. This would be consistent with the long standing survey evidence that most people had little interest in the European debate until the referendum was called.

– therefore, the referendum vote (and current attitudes?) are more to do with gut feelings – culture, emotion, loyalty – than specific policies, and attitudes are more likely to be swayed by notions like “control” and “betrayal” than anything actually in the negotiations.

Friedrich, I don’t think that even the parties themselves have any idea what their own negotiating stance is. Such is the division even within the parties, and the uncertainty about what to do for the best. Of course it’s clear that there can be no such thing as a “good Brexit”. Even a slightly closer examination of a single detail such as the Irish border shows that – how can it possibly be reconciled? And potential “benefits”? This survey indicates again that most leave voters don’t even really know what they mean by sovereignty.

But as we rush towards the light at the end of the tunnel, which has now turned out to be the oncoming train, it seems no-one in power has the courage to do anything about it. For my money the only possible way out is a second referendum. As much as the first caused all this damage, it will take something equally reckless to turn it around.

You state that the baseline is ‘no deal’ and that it implies “the loss of rights of EU citizens currently residing in the UK”.

You display this on the graph by placing “All must leave” on the reference line in the middle but “the loss of rights of EU citizens currently residing in the UK” is NOT equivalent to “All must leave”.

The loss of SOME rights does not enable the UK government to mass deport about 5% of the resident population.

The options you selected for “Rights of EU citizens” go from negligible loss of rights to mass violation of human rights. Why this span?

Haven’t you skewed the results by extending the spectrum of choices in one direction only?

Wouldn’t it be more interesting if you had included the option “All can stay indefinitely and all acquire the right to vote in general election”?

To state that I was surprised and disgusted to read The Independent’s headline “29% of Remain voters would accept expulsion of all EU nationals after Brexit” would be the understatement of the year. I don’t like the outcome of this study, but that’s not a reason to be angry. What I am angry with, is the media’s misinterpretation of the results, and the academic ignoring of the ethical and methodological issues arising from this study.

I acknowledge the academic curiosity to undertake these conjoint experiments, to show people the complexity of Brexit by giving them the choice between several scenarios, without the option to back out with an “I don’t know” answer.

The trouble lies in the fact that some of these scenarios are hypothetical at best. The EU-27 has made clear over and over again that there won’t be any cherry-picking. When the UK wants to retain its current access to the single market, then the UK will have to comply with the EU pillars of freedom (with freedom of movement being one of them). In other words, the UK would not be able to restrict EU-immigration more than it already can do now (that the UK doesn’t use these powers is a different matter). Therefore, to present an option that for instance combines unfettered access to the EU single market with the expulsion of all EU citizens from the UK, is nothing but a nice academic hypothetical that at best only serves to demonstrate how ill-informed ‘the British people’ are on Brexit and its implications. Indeed, your assessment that “ultimately, citizens are indifferent about many aspects of Brexit” is – much to my regret – correct.

In its article on your study, the Independent wrote “Twenty-nine per cent of Remain voters would be willing to accept a [deal] that contained that feature, against a set of alternatives.” However, in your study you used this gliding scale between 0 and 100, meaning, respondents had more than a binary yes/no answer option. Therefore this does not say that 29% of Remain voters would accept EU citizens to be mass-deported. It only states that 29% of Remain voters would be ok with a deal that does not guarantee EU citizens to maintain the rights they have now. After all, the percentage values are a representation of the average degree of approval each scenario gets, not the percentage of respondents who favour it. How much different this new deal would be from existing rights… I don’t know. Perhaps a peer review could clarify this.

On top of that, we can debate the statistical significance, bearing in mind that in December 2016, the total number of UK parliamentary electors stood at 45,766,000. And there you are with 3,200 respondents. And how many of them were Remain voters?

By no means do I intend to restrict you in your academic work, even when it delivers controversial outcomes. However, using the research methodology you picked, you have played an active part in electorate and media antagonism, and over the last couple of years we have seen that words have consequences. The media took the results of your study, turned it into a juicy (because: controversial) headline, and before you know it, extremist xenophobe will interpret your study as a seal of approval for their hate crimes. Of course you are not responsible for whatever headline the media come up with, but judged from your Twitter accounts and a subsequent article in the Independent, you revelled in the attention first, only then to point out the inaccuracy of that 29% headline. And this is where it left me wondering whether this study was still in line with the ethical and methodological guidelines of academic research.

I see a weakness in the “One-off Payment” feature.

I reckon essentially nobody in the sample had familiarity with amounts of money in the range £10 billion – £70 billion: how many people have a mortgage of £10 billions or more? how many people run a business worth those figures?

For the layman these amounts are so big that they all mean just “a lot of money”.

I suspect that the answers do not provide any meaningful insight on the estimates the participants may have reached themselves.

The study can only reveal whether people have been “primed” after hearing two-digits figures in the media and how generally unpleasant is the prospect of paying money.

Analysis is bias and skewed, does not reflect what a Leave voter would agree as options, just a Remain voter.

You may find this interesting

“Huge New Study Reveals What The British Public Really Want From Brexit”

https://www.buzzfeed.com/jamesball/remain-and-leave-voters-are-surprisingly-united-on-backing?utm_term=.pxNBNAewb3#.ex2oeDOzx9

68 % want hard brexit

67% Prefer no deal

I really hope you’re posting this to be ironic.

This buzzfeed ‘article’ was based of their inability to interpret the analysis done by the LSE. Which is the reason why the two professors who did the research have had write this blog which is in effect a complete debunking of the post you’ve added.

Unless I have misunderstood them, this is a serious misrepresentation of the findings. Surely needs a correction?

There were 2 main problems with your analysis and communications. Firstly you failed to explain that this isn’t a normal survey and the individual scores do not represent the proportion of respondents that favour a particular policy/outcome. Secondly, your definitions of “Hard”, “Soft” and “No Deal” fall woefully short. As the main definition of “Hard” or “Soft” and WTO (“No Deal”) are related to trade, your definitions of each as:

“Hard” Some administrative barriers to trade in goods and services and 5% average tariff on goods

“Soft” Few administrative barriers to trade in goods and services and no tariffs on goods

“No Deal” Some administrative barriers to trade in goods and services and 2.5% average tariff on goods

These are patently not the definition of Hard, Soft or No Deal with regard trade. This is firstly because “Hard” and “No Deal” should have the same definition, secondly because of the lack of services being included in tariffs, thirdly because both “Hard” and “No Deal” would mean many administrative barriers, whilst “Soft” means no administrative barriers.

Similar points could be made about the “all can stay indefinitely” and “Must apply for ‘leave to remain’ under the same terms as people from non-EU countries” for “No Deal” and “Hard”.

On another point your clarifications have also been poor, almost as though you don’t understand the results. In fact in the conclusion here you appear to contradict your findings:

“Remain voters care much more about the rights of EU citizens – indeed, no other aspect of the negotiations appears to matter more to them. They also agree with Leave voters that trade terms with fewer barriers and lower tariffs than a “no deal” scenario would bring are preferable to a hard break from the common market. Yet, ultimately, citizens are indifferent about many aspects of Brexit.”

This indicates that both Leavers and Remainers actually prefer a “Soft” Brexit.

3/10