After a summer of squabbling by UK Cabinet Ministers and growing exasperation on the EU side, Theresa May’s Florence speech was supposed to clarify what the UK wants from Brexit. But are we any clearer on what sort of arrangement the UK seeks or what it is prepared to concede to obtain it? Probably not, writes Iain Begg (LSE European Institute).

She largely reiterated what she had said in her Lancaster House speech in January 2017: the UK will be leaving both the single market and the customs union, and an eventual deal will be bespoke. We can look forward to a relationship closer than the Canada EU deal (CETA), but not as close as membership of the European Economic Area. There is a somewhat stronger statement on Britain remaining in certain EU programmes, such as for research, and no longer the veiled threat some saw in January about withdrawing security cooperation.\

a longer transitional period seems now to have been accepted as unavoidable

Having a longer transitional period after 29th March 2019, during which many features of EU membership will remain in place, seems now to have been accepted as unavoidable, even if answers are still needed to the simple question that has dogged transition throughout: ‘to what?’. Business will undoubtedly welcome this, but carping can be expected from those – Ringo Starr included – who just want us to get on with it.

A key commitment is made on the EU’s finances and will be seen as an important concession. She does “not want our partners to fear that they will need to pay more or receive less over the remainder of the current budget plan as a result of our decision to leave”. The plan in question is best interpreted as the EU’s Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF), which runs from 2014-2020. In practice, the remainder means from March 29th 2019 to the end of 2020.

Over this period, the UK’s net contribution to the EU would have been of the order of €18-20 billion. It is an evident advance on Boris Johnson’s statement that the EU can ‘go whistle’, but a long way short of the figure of as much as €100 billion floated on the EU idea. The trouble, though, is (as previously explained) the many disputed elements of exactly when an MFF ends, given the overhang of commitments for the likes of research and economic development projects, not to mention whether or not the UK is liable for a share of the costs of the pensions of EU employees.

On the budget issue, the May speech also has the slippery phrase “we can only resolve this as part of the settlement of all the issues I have been talking about today”. If this signals prolonging the resistance to agreeing on a budget settlement – one of the three issues, with the Irish border and the rights of each others’ citizens, the EU has consistently said have to be settled before moving on to the future economic relationship – it does not augur well for making rapid progress.

Despite the reassuring language about Ireland in the speech, there are no new insights about how to avoid a hard border if the UK is outside the customs union. Granted the political will is there and the Florence speech reaffirms it, but in this as in many other areas details matter.

May is right to stress the need for certainty, but unconvincing on delivering it

She is right to stress the need for certainty, but unconvincing on delivering it. The importance of a deal on services is hinted at, but the risks of not doing enough need to be further explored. Business services, as well as financial services, tourism, digital services and the creative industries are the sectors of the UK economy potentially at risk if this facet of a deal is not given greater attention.

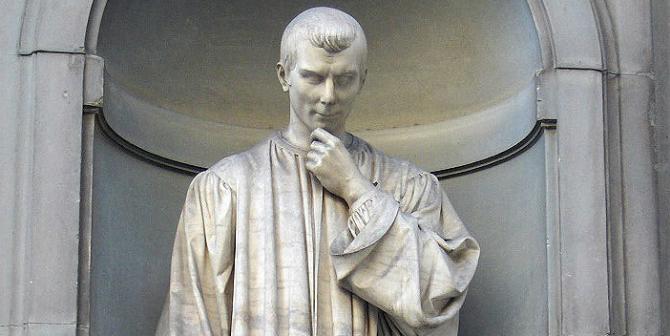

Statue of Machiavelli at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. Attribution 3.0 Unported

Statue of Machiavelli at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. Attribution 3.0 Unported

If Theresa May’s Florence speech was intended to be a game-changer, the only credible verdict is that whatever the game has not changed much. She has probably done enough to keep her cabinet behind her (or, at least, to persuade them not to wield the knives yet) and by softening the UK stance on the vexed issue of the ‘divorce bill’ has partly unblocked an issue standing in the way of moving to the next stage of negotiations.

Perhaps she has taken to heart the advice of a renowned denizen of Florence, Niccolo Machiavelli, who once explained: “benefits should be conferred gradually; and in that way they will taste better”.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Iain Begg is a Professorial Research Fellow at the European Institute and Co-Director of the Dahrendorf Forum, London School of Economics and Political Science.

I see the Prime Minister as an honest woman seeking to honour the vote of 17.4 million Britons in the face of obstruction from almost every quarter. Her speech in Florence was conciliatory and offered more constructive thought on the way forward than we have ever heard from Monsieur le Barnier.or the president of the EU Commission. My only concern, regardless, of the length of any agreed transitional period, is that it will relate solely to revision of existing trading agreements. This must not hinder the formal repeal of the UK /EU treaty to be effective at the end of March 2019.