On September 22, Theresa May’s speech in Florence ostensibly outlined a way forward on Brexit. Is the £20bn on offer too much, too little or too late? Are promises to protect the rights of EU citizens in the UK real or merely rhetorical? What will happen next – renewed dialogue with Brussels or a bust-up with Boris and other Brexiteers? Yet in all this hubbub, an important dimension of May’s new discourse has been overlooked: security as a core policy objective, writes Jennifer Jackson-Preece (LSE).

On September 22, Theresa May’s speech in Florence ostensibly outlined a way forward on Brexit. Is the £20bn on offer too much, too little or too late? Are promises to protect the rights of EU citizens in the UK real or merely rhetorical? What will happen next – renewed dialogue with Brussels or a bust-up with Boris and other Brexiteers? Yet in all this hubbub, an important dimension of May’s new discourse has been overlooked: security as a core policy objective, writes Jennifer Jackson-Preece (LSE).

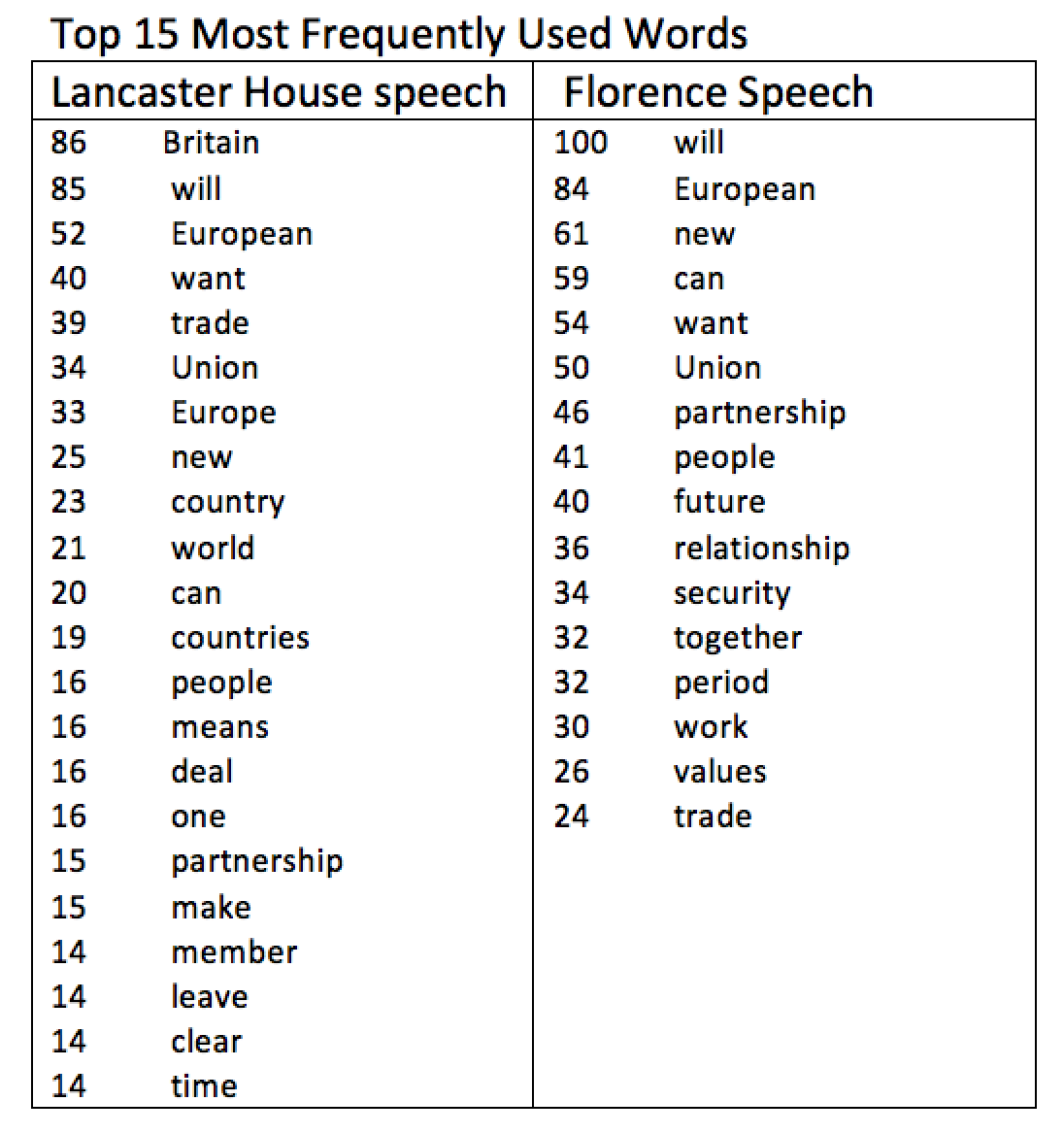

The resurgence of security over and above trade is not what one would expect in a speech purporting to set out the UK’s position on how to move Brexit talks forward. It also stands in stark contrast to the earlier Lancaster House speech. In February 2017, the word security was never spoken at Lancaster House. In September 2017, security was repeated 34 times in Florence, making it the eleventh most frequently used word in May’s speech. In contrast, whereas trade was flagged 39 times in the Lancaster speech – making it the fifth most frequently used word – in the Florence speech, trade got only 24 mentions, dropping to fifteenth place in overall word frequency.

What explains the appearance of a security discourse? That the UK has experienced five terrorist attacks since February is undoubtedly an important factor. This is also a policy area and discursive style in which May is comfortable and confident. The linking of ‘migration and terrorism’, the identification of each as ‘challenges which respect no borders’, the promise to ‘crack down on the evil traffickers’ and the clarion call to ‘fight against terrorism’ – all used in the Florence speech – are rhetorical devices May frequently employed in her long tenure as Home Secretary. This is, of course, also the rhetoric favoured by the Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum. Thus it is hardly surprising that the Leave language of ‘control’ features as the inevitable corollary of ‘threat’: each appears fourteen times in the Florence speech. Neither was mentioned in the Lancaster House speech.

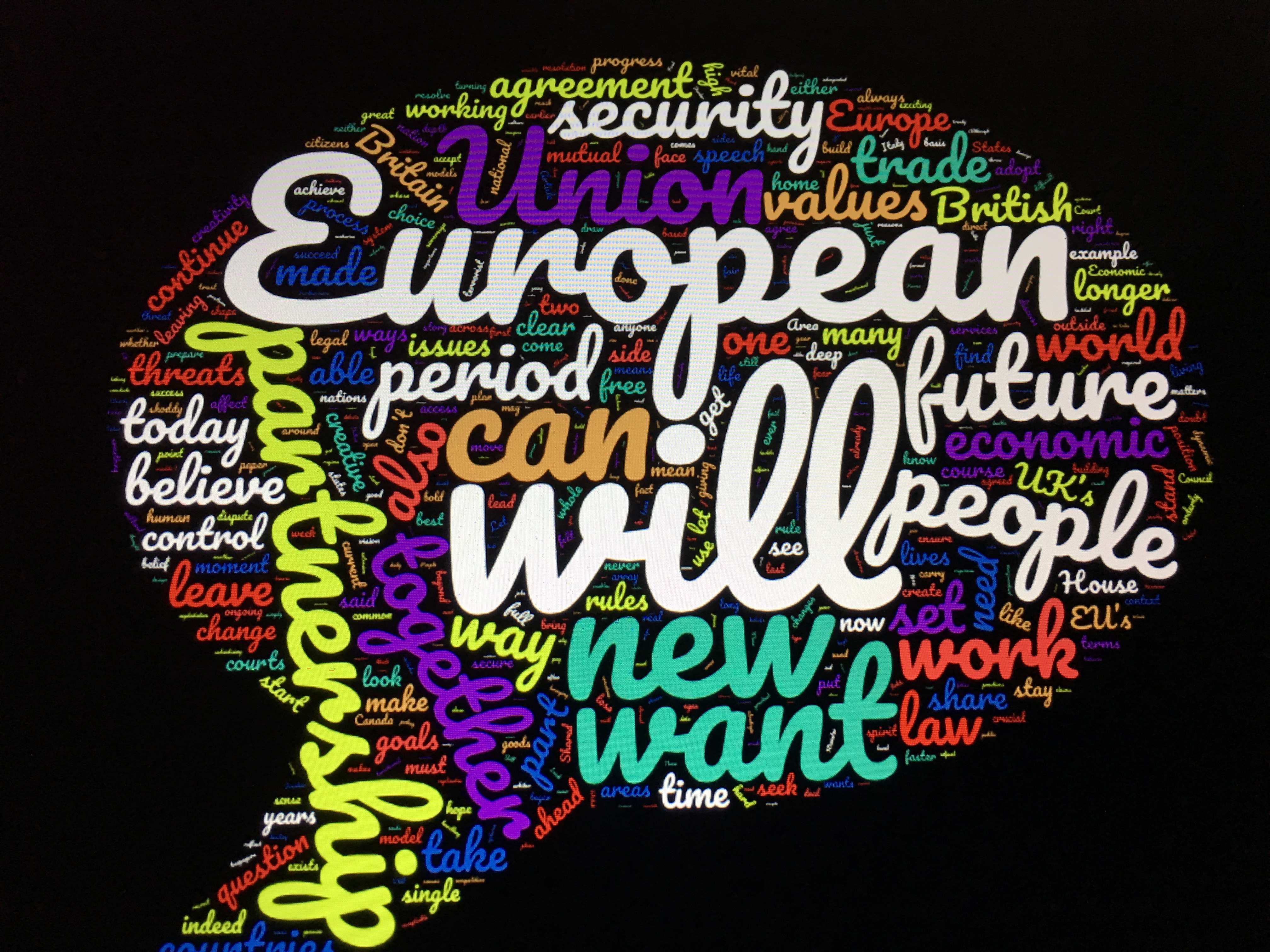

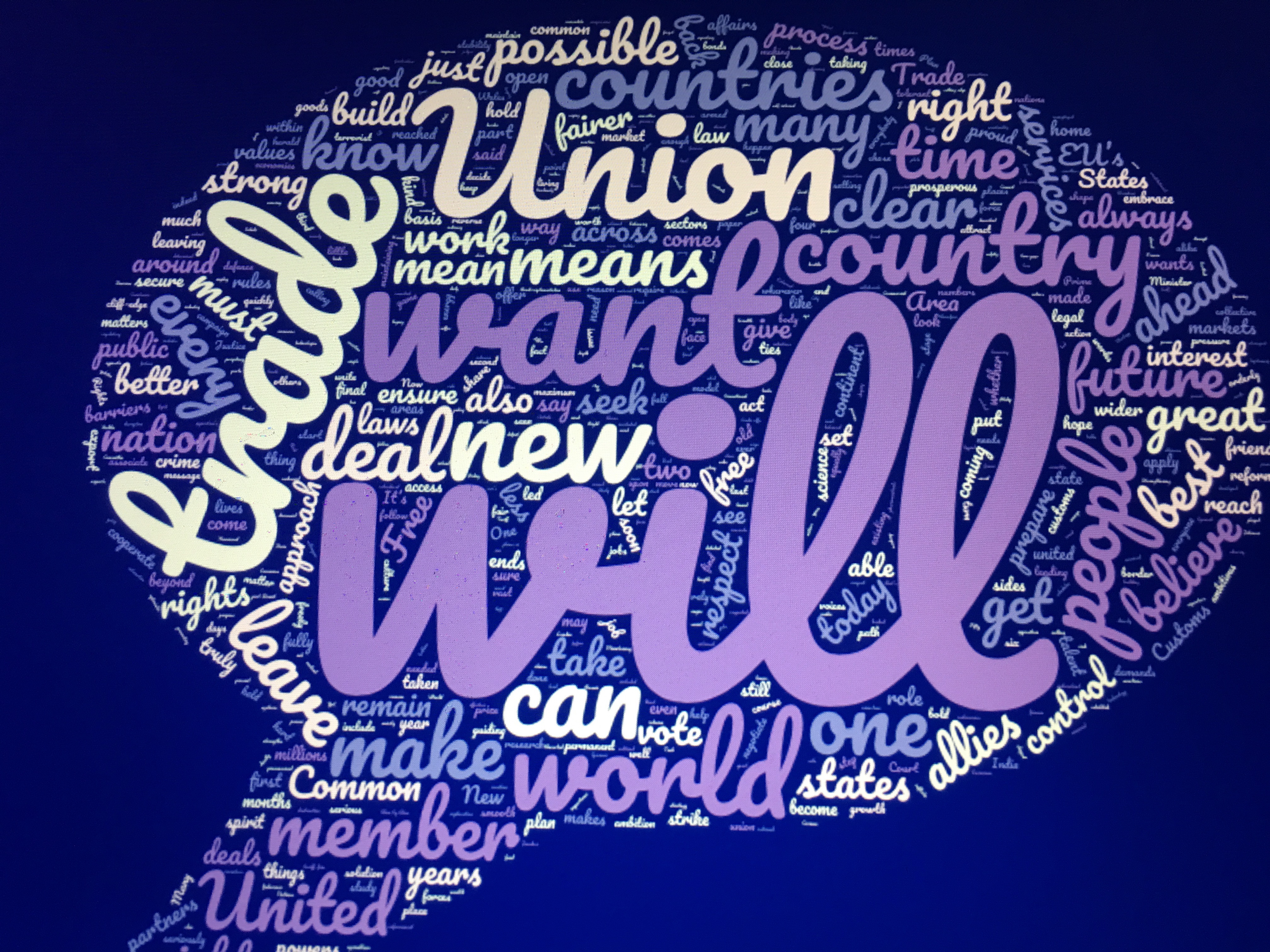

Florence speech bubble

What then are we to make of May’s vision for the future? Is the new UK-EU partnership to be based on a deep mutual fear – of migration, terrorism trafficking, climate change, nuclear proliferation, territorial aggression, instability, civil war – all are purposefully invoked in the Florence speech. Clearly UK – EU security cooperation is a common interest and should be maintained post-Brexit. But surely a future partnership, particularly one intended to embrace ‘new thinking and new possibilities’ to ‘forge a better, brighter future for all our peoples’ should be built on more than fear and desire for greater domestic control?

Lancaster House speech bubble

More fundamentally, by reinforcing the language of (in)security, May risks securitising the future relationship with the EU itself. Europe has long been imagined in the U.K. as the bogeyman of Britain – a continent of war, despotism, democratic deficit, mass migration, human traffickers, and terrorists. Eurosceptics who draw upon this securitised discourse do so to construct Europe and the European Union as an existential threat to British sovereignty and society. Britain’s decision to leave the European Union was in no small part a consequence of the securitisation of Europe in British public discourse. Return to the discourse of security now is unlikely to produce a constructive dialogue. If it fans the flames of a renewed Euroscepticism in the Conservative Party and the popular press, May could find herself back on the cliff edge.

May risks securitising the future relationship with the EU

Now, more than ever, we need a discourse of constructive engagement. This makes projects like Generation Brexit particularly timely and important. Generation Brexit is a pan-European, multilingual youth consultation on The future of UK-EU relations. If you are under 35, and want a future UK – EU relationship built on something other than mutual fear, go to www.generationbrexit.org.

This blog represents the views of the author and not those of LSE Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Dr Jennifer Jackson-Preece is Deputy Head of the European Institute and Associate Professor of Nationalism, with a joint appointment in both the European Institute and the Department of International Relations, LSE.