Why did people really vote to Leave or Remain? Noah Carl (Centre for Social Investigation) examines four different polls, and finds that immigration and sovereignty headed Leavers’ reasons – contrary to suggestions that the vote was intended to ‘teach politicians a lesson’. Leavers also proved better at characterising Remainers’ reasons than vice versa – something which may be linked to progressives’ greater tendency to disengage from their political opponents.

Why did people really vote to Leave or Remain? Noah Carl (Centre for Social Investigation) examines four different polls, and finds that immigration and sovereignty headed Leavers’ reasons – contrary to suggestions that the vote was intended to ‘teach politicians a lesson’. Leavers also proved better at characterising Remainers’ reasons than vice versa – something which may be linked to progressives’ greater tendency to disengage from their political opponents.

Three separate surveys/opinion polls conducted around the time of the referendum asked Britons why they voted the way they did. These all found more or less the same thing, namely that the two main reasons people voted Leave were ‘sovereignty’ and ‘immigration’, and that the main reason people voted Remain was ‘the economy’.

First, YouGov asked Leave and Remain voters to say which reason from a list of eight was the most important when deciding how to vote in the referendum. The most frequently selected reason among Leave voters – ticked by 45% – was ‘to strike a better balance between Britain’s right to act independently, and the appropriate level of co-operation with other countries’. The second most frequently selected reason among Leave voters – ticked by 26% – was ‘to help us deal better with the issue of immigration’. The most frequently cited reason among Remain voters – ticked by 40% – was ‘to be better for jobs, investment and the economy generally’. Interestingly, the second most frequently selected reason among Remain voters was the same as the most frequently selected reason among Leave voters (given above).

Second, Lord Ashcroft asked Leave voters to rank four possible reasons for voting Leave, and asked Remain voters to rank four possible reasons for voting Remain. The two most important reasons for voting Leave were: ‘The principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK’, which was ranked first by 49% of Leave voters; and ‘A feeling that voting to leave the EU offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders’, which was ranked first by 33% of Leave voters. The two most important reasons for voting Remain were: ‘The risks of voting to leave looked too great when it came to things like the economy, jobs and prices’, which was ranked first by 43% of Remain voters; and ‘A vote to remain would still mean the UK having access to the EU single market while remaining outside of the Euro and the no borders area of Europe, giving the UK the best of both worlds’, which was ranked first by 31% of Remain voters.

Third, the British Election Study team asked their respondents an open-ended question just prior to the referendum, namely ‘What matters most to you when deciding how to vote in the EU referendum?’. They coded the responses into 54 categories encompassing the key themes that respondents mentioned. The most frequently cited reasons for voting Leave were ‘Sovereignty/EU bureaucracy’ and ‘Immigration’ (both mentioned by around 30% of those who said they intended to vote Leave). By far the most frequently cited reason for voting Remain was ‘Economy’ (mentioned by nearly 40% of those who said they intended to vote Remain).

CSI’s data on why people voted Leave or Remain in the EU referendum

Approximately 3,000 respondents were surveyed online by the polling company Kantar between 2 February and 8 March, 2018. To begin with, we asked Leave voters to rank four reasons for voting Leave in order of how important they were when deciding which way to vote in the referendum. Figure 1 displays the distribution of Leave voters by rank for each of the four reasons. (Note that the wording of each reason is exactly as it appeared in the online survey.) The reason with the highest average rank is ‘to regain control over EU immigration’. The reason with the second highest average rank is ‘didn’t want the EU to have any role in UK law-making’.

Notes: Each bar shows the distribution of Leave voters according to how they ranked the corresponding reason for voting Leave. Bars are ordered from left to right by the percentage-weighted mean rank. Sample weights were applied.

Interestingly, ‘to teach British politicians a lesson’ has by far the lowest average rank, being ranked last by a full 88% of Leave voters. This contradicts the widespread claim that Brexit was a ‘protest vote’: i.e., that people voted Leave as a way of venting deep-seated grievances about things such as inequality, austerity and social liberalism, rather than because they opposed Britain’s membership of the EU per se.

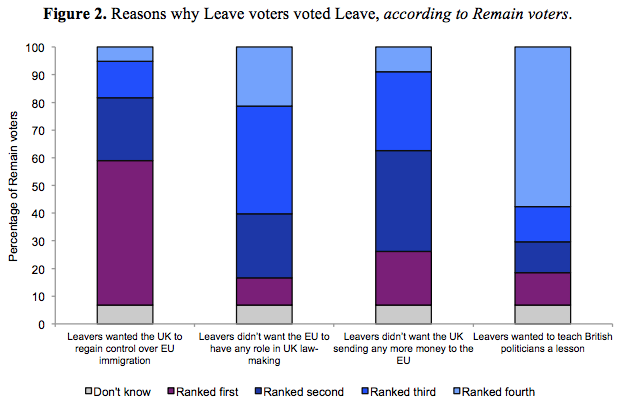

We then asked Remain voters to rank the same four reasons in order of how important they thought those reasons were to Leave voters. (When answering this question, Remain voters were given the option to say ‘don’t know’.) Figure 2 displays Remainers’ assessments of Leavers’ reasons for voting Leave. It shows that Remain voters overestimate the importance that Leave voters attach to both regaining control over EU immigration and teaching British politicians a lesson. 52% of Remain voters rank ‘Leavers wanted the UK to regain control over EU immigration’ first, whereas only 39% of Leave voters rank ‘to regain control over EU immigration’ first. And 12% of Remain voters rank ‘Leavers wanted to teach British politicians a lesson’ first, whereas only 3% of Leave voters rank ‘to teach British politicians a lesson’ first. By contrast, Remain voters dramatically underestimate the importance that Leave voters attach to the EU having no role in UK law-making. Only 10% of Remain voters rank ‘Leavers didn’t want the EU to have any role in UK law-making’ first, whereas 35% of Leave voters rank ‘didn’t want the EU to have any role in UK law-making’ first.

Notes: Each bar shows the distribution of Remain voters according to how they ranked the corresponding reason for voting Leave. Sample weights were applied.

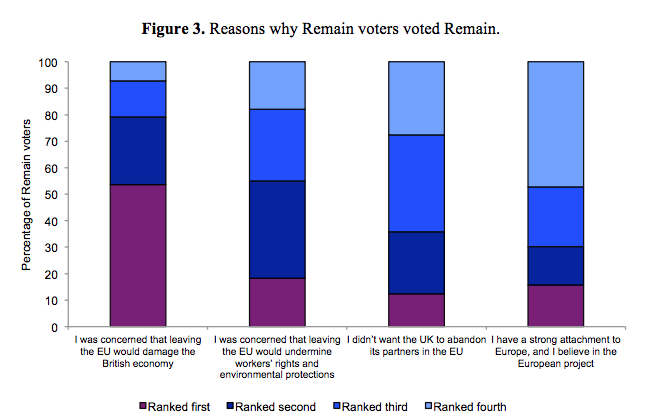

We also asked Remain voters to rank four reasons for voting Remain in order of how important they were when deciding which way to vote in the referendum. Figure 3 displays the distribution of Remain voters by rank for each of the four reasons. Unsurprisingly, ‘leaving the EU would damage the British economy’ has by far the highest average rank, being ranked first by a full 54% of Remain voters. More interestingly, the reason with the lowest average rank is ‘a strong attachment to Europe’, which comports with the claim that Britons have a relatively weak sense of European identity.

Notes: Each bar shows the distribution of Remain voters according to how they ranked the corresponding reason for voting Remain. Bars are ordered from left to right by the percentage-weighted mean rank. Sample weights were applied.

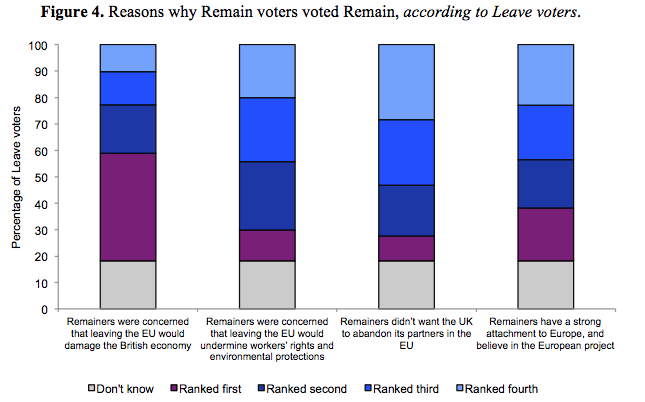

As before, we then asked Leave voters to rank the same four reasons in order of how important they thought those reasons were to Remain voters. Figure 4 displays Leavers’ assessments of Remainers’ reasons for voting Remain. It shows that Leave voters slightly overestimate the importance that Remain voters attach to Europe and the European project. 20% of Leave voters rank ‘Remainers have a strong attachment to Europe, and believe in the European project’ first, whereas only 16% of Remain voters rank ‘a strong attachment to Europe’ first.

Notes: Each bar shows the distribution of Leave voters according to how they ranked the corresponding reason for voting Remain. Sample weights were applied.

Overall, however, Leave voters characterise Remain voters more accurately than Remain voters characterise Leave voters (despite the fact that Leave voters were more likely to say ‘don’t know’). This is apparent just by visually comparing Figures 1 and 2 versus Figures 3 and 4. However, to check more precisely, I calculated the sum of the absolute differences between the percentages in the various segments of the Figures, for each of the two pairs. The discrepancies between Figures 1 and 2 summed to 173 percentage points. By contrast, the discrepancies between Figures 3 and 4 summed to only 101 percentage points. This finding is consistent with evidence from the United States that conservatives hold more accurate stereotypes about progressives than progressives do about conservatives.

Why then do Leave voters characterise Remain voters more accurately than Remain voters characterise Leave voters? Two possible explanations are as follows. First, according to several reports on media coverage of the referendum campaign, the ‘economy’ was the most frequently mentioned issue, and ‘immigration’ was mentioned far more often than ‘sovereignty’. Given that many partisans on both sides will have been exposed to their opponents’ arguments primarily via the popular media, this may explain why Remain voters underestimate the importance that Leave voters attach to the EU having no role in UK law-making (i.e., sovereignty). On the other hand, when David Levy and colleagues analysed media coverage at the level of individual arguments, they found that Leave campaigners actually mentioned ‘sovereignty’ more often than ‘immigration’. Second, there is a certain amount of evidence that progressives are more likely to block or ‘unfriend’ their ideological counterparts than conservatives. For example, a 2014 YouGov poll found that 42% of Liberal Democrat supporters said they would find it harder to be friends with someone who became a UKIP supporter, whereas only 10% of UKIP supporters said they would find it harder to be friends with someone who became a Liberal Democrat supporter. For this reason, Remain voters may have had less exposure to Leave voters’ arguments than vice versa.

An important methodological caveat is that the data presented here concern people’s stated reasons for voting Leave or Remain, assessed more than 18 months after the referendum took place. It is therefore possible that they do not reflect the true reasons people voted the way they did. For example, they could be biased by the tendency for people to justify their decisions with post-hoc rationalisations. On the other hand, Figures 1 and 3 accord rather closely with the findings of previous surveys and opinion polls.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It is an edited version of CSI Brexit 4: People’s Stated Reasons for Voting Leave or Remain, April 2018, where full references can be found.

Noah Carl is a post-doctoral researcher at the Centre for Social Investigation.

People who voted leave told you what you wanted to hear

This is interesting, but I am always wary of any survey that asks respondents to say why they did something – especially when they might believe that answering in a certain way might put them in a bad light. That is, if you answer that curbing immigration is your number one priority, people might call you a xenophobe – you might very well feel that this can only be a privately held view, not a publicly held one, and therefore fudge your answer.

The word “racist” or “xenophobe” has been thrown around with such abandon in all sorts of silly uses that it now has no meaning to leave voters. This is a shame because real racists now feel free, aka anti-semitism in the Labour party.

The next words that are becoming debased are “fascist” and “Nazi”

Anybody who comes up with leave voters are thick northern.racists, I just put in the stupid category (you have not said this).

None of the surveys asked people why they voted as they did. They all assumed multiple reasons and asked respondents to rank them, which is quite a different thing. In addition survey data are always anonymised. So there is no good reason to doubt that answers by both leavers and remainers were truthful.

I totally agree on your first point. Your second point depends on the assumption that people will only distort the truth in their responses if they are trying to mislead others about their motivation. It is also possible that they might be misleading themselves about their motivation.

I think Elizabeth Noelle-Neumann’s “The Spiral of Silence” gives a very good and relevant account of social conformity. It could be interpreted as providing a very plausible account of why the nationalist right have been relatively silent for so long and then have exploded full of festering resentment and accusation (that might be difficult to explain without the “spiral of silence” hypothesis) It might also explain why the belligerent voices of Brexit have succeeded, not in persuading the public of the logic of Brexit but persuading them that there has been a shift in public opinion just from the aggression, volume and media coverage of what would otherwise have been an issue of marginal interest to most. My point in relation to the “Spiral of Silence” hypothesis is that no one ever wants to admit, even to themselves, that they were motivated by an impulse to conform to, or at least not oppose, what they perceive to be a majority view or a rising opinion. Yet if the spiral of silence hypothesis is correct this is a very widespread cause of apparent shifts in public opinion.

Perhaps Leave voters are well aware that the adverse impact on the economy is one howlingly obvious consequence of Brexit, so it was easier for them to deduce Remainer thinking than for Remainers to deduce Leaver thinking.

Many people must have attempted to balance a number of different factors in reaching a decision. As a Remainer, I was influenced, among other things, by the ideals behind the European project as a response to dire twentieth century history, global environmental issues, Erasmus and opportunity for youth, freedom of movement, the common good, the size and potential influence of the UK in an inreasingly protectionist trading world, the likely impact on jobs, public services including the NHS, etc. I was also mindful of the arguments about ever closer union, the need to revisit globalism/neoliberalism, and the decline of the nation state. There are ideals and pragmatism on both sides of the divide. I chose Remain because I believe we will fare better, in every way and not just economically, in the biggest, most sophisticated internal market in the world. Shoe-horning beliefs and convictions into these polls may be less than wholly convincing, because the answers given are, in themselves, compromises.

Even if the conclusions from this research are correct, which is moot, it’s difficult to see where it takes us and how the civil war created by the Tories can be resolved.

The title of this article overstates what the research shows, if anything.

The methodology is open to question because of the danger that a researcher (using this methodology) could unknowingly bias the results with their own preconceptions or prejudices in the way that the “reasons for leaving” and “reasons for remaining” were formulated both in their content and their framing.

Framing above all makes a big difference to peoples perceptions (and what aspect of a complex issue people respond to) as we have seen with the “second referendum” ,”referendum on the outcome” debate. The same thing can look more or less attractive to the same voters depending on how you describe it and therefore what aspect of the issue you highlight and bring to their attention.

I think that “Leave voters wanted to teach British politicians a lesson”. was framed in a way that would make it a particularly unattractive description to leave voters but that would convey something that remain voters would recognise as significant. Other ways of framing this viewpoint such as “Leave voters were angry at the failure of British politicians to understand their concerns” might have led to a different response from leave voters, but formulating questions of this sort is unreliable and fraught with unforeseen errors. Overall it is very difficult to stop sympathy or antipathy to a particular viewpoint from affecting the way that questions are phrased. Overall I do not think research of this sort is capable of providing anything from which you can draw any reliable conclusions.

OK but questions condition answers so I only buy it on the basis of these questions. And yes there’s a hell of a lot of post-hoc rationalisations

Remainers don’t understand the motivations, concerns and thought logic of Leavers not because they’re dumb, but because they refuse to. They prefer to live in denial, and smear everyone else who doesn’t fit their worldview or think the same way as they do as political abominations of all slurs. That one statistic quoted in this article on how UKIP voters were more likely to keep friends who don’t think the same way as they do, than self-declared “progressive liberals” who support the Lib Dems says a lot about each group.

Leavers are willing to listen to Remainers trying to convince and work with them to solve or meet their concerns about immigration and national sovereignty/status that isn’t the same old charade that was run since the 1990s, but Remainers aren’t even willing to listen to Leavers and recognise that their concerns are justifiable and have a very real impact from their point of view. Till now, such lessons have not been learnt. Both sides are now stuck in a civil war against each other, tearing the country down the middle with increasing intolerance and just waiting for things to fall apart so as to bring out the accusations of betrayal and backstabbing against each other.

Truly, the UK is now a sad country made of men who are lesser sons of greater sires.

Andy, there is an old idiom “the pot calling the kettle black” that fits your comment about Leavers and Remainers.

There is no evidence other than anecdotal about whether Leavers or Remainers understand each other’s positions at all. The main reason for this is there are a myriad of reasons for either position, just witness what is going on in the Conservative government and Party at large. Certainly there is no evidence for your statement that “(remainers) prefer to live in denial and smear everyone else who doesn’t fit their world view…”

Nor is there any evidence for another of your statements “Leavers are willing to listen to Remainers trying to convince and work with them to solve or meet their concerns about immigration and national sovereignty/status…”

As far as the evidential basis for the article, I have questioned that in my earlier comment and in fact the author himself questions the basis for the conclusions he has made in the last paragraph of the article.

I prefer my analysis to be based on facts, not opinions

Andy, your analysis (and this poll result) are very accurate in my experience. I’m a Leave voter who has spent many hours on Remain Facebook pages discussing the posts the Remainers there publish. Many are smears of Leavers with no foundation or fact. When they demand facts from me and I provide them (links to EU Parliament documents, YouTube videos of speeches by Commissioners, etc) they always ask ME to justify my point or tell them where the problem is. They never look at the evidence I’ve provided – even blatently saying telling me so – and always rubbish such documents or my extracts of them with comments like “it’s only a working document” or “this policy will be vetoed bu the MEPs” , When I point out the quotes from Macron and Juncker supporting these policy/Treaty changes and published quotes that show vetoes will not be available to MEPs (“majority voting should be the default” voting system and vetoes should be stopped) either the silence is deafening or they just ridicule me personally as some kind of weirdo obsesssive. They just don’t want to know anything that might undermine their “correct” view of the world. In contrast, I’m on this site to see if they have better info than I have, facts I’m not aware of, or videos I’ve not seen – in line with your comments.

I think David if you look back you will see your prior “analysis” was based on your expressed opinion about people’s unexpressed motivation. What were the “facts” you leant on? In any event, even if leave voters were offering post hoc rationalisations 18 months later, consideration of the survey data from nearer the time would suggest the misestimation by remain voters of their motivation was considerably worse, not better.

“Ever closer union” will likely necessitate ever more centralised (EU) governance, including judicial and fiscal control, and possibly even compulsory adoption of the Euro.

Despite that, the question which never gets asked is: Do “remainers” seek to accept all future EU demands,”come what may” or do they advocate a series of crippling “Brexit” referendums, one for each step of devolution as the EU pursues its stated goal of “ever closer union?”

So yes, it would be very good to know what the “remain” camp actually wants for our future.

It’s probably that Conservatives are more likely to be disonest about their real motivations. Or even lacking self-insight.

For example, after decades of having it hammered it into us that racism is bad, those with racist attitudes are surely likely to hide them? In contrast, what would liberals have to hide? That they are secret vegans?

67% voted Remain in 1975. Go forward 41 years, and it’s 48%. The massive projected fall over those 41 years told me a lot before I voted Leave. Interestingly, 70% of 18-24 year olds voted Remain this time, almost the same as the population in 1975. I think this is called “experience” (and I’m 30).

https://www.statista.com/statistics/567922/distribution-of-eu-referendum-votes-by-age-and-gender-uk/

Look at how young females massively outweigh the male Remain vote, but by the time they reach 60+, it is they who are the bigger Leave voters by gender. The EU wants to tug on your heart strings, but you end up very, very disappointed.

You can claim it’s experience and then try to represent yourself as wise, but it’s just as likely that the odler you are, the more you remember the days of empire, and the less in touch you are with the concerns facing those who still need to work in a successful economy.

It’s _really_ easy to check the box that says “We weren’t striking the rightbalance with the EU”… I’d be fascinated to know how many of the people who picked that option are able to give specific, concrete examples of their concerns…

The one I heard a lot leading up to the referendum was “to avoid burdensome regulations”. When my fatehr pulled that out as his top reason and I asked which regulations in particular were a problem, he couldn’t reference a single one.

I know it’s only anecdotal, but you’ve basically given a plethora of “respectable” answers – it’s hardly surprising people [on both sides] picked them

I would suggest that the study is about right. But I see the comments from Remain voters are the usual middle-ground eroding nonsense. By removing the middle ground of politics and stating that one side are clearly racist and stupid, the other liberal and morally righteous and of superior intellect is serving only to widen the gap. The truth is both leave voters and remain voters exist in the same households. Do we really want a cull of one or the other because that would seem to be the only viable outcome for inhabiting the same island together?

Remain voters that want to overturn the outcome of the referendum need to ask themselves this: Is the overlord that rules by blood right and might and better than the overlord that rules by superior intellect (and genetics)? That is what we are bound for if the referendum is overturned.

However. If the decision were followed through and a subsequent generation sought to rejoin the EU, then that would be a different matter.

Like many others, I voted leave because I was promised more control over immigration. But surely we can’t do this while there is an Irish border that anyone can cross unchecked? I’ve now learned that the Good Friday Agreement is a legally binding international treaty that effectively prohibits checkpoints along this border. So how could we ever keep control over it? I feel misled by the Leave campaign (and a victim of my own ignorance) for voting for something that now appears to have been undeliverable right from the start. Or am I making further inaccurate conclusions now?

Leavers do have a much better understanding of remainders motivations than vice-versa.

Heres why.

Remainers have for the past 4 years been espousing the benefits of EU membership, making it clear to all who will listen to all the positive things we get from it, and how damaging it will be for the UK to leave, in clear documents, evidence from experts in the field, ensuring that people capable of understanding know all they need to know.

whereas the “leavers” for three years have said “we voted to leave”…and that’s about it!

so yeah you’re fucking right…we ain’t got a fucking clue why you want to leave, except for reasons that are based on proven lies, corruption and documents bullshit!

maybe that’s because for three years we’ve been asking “tell me one good thing you as an individual will benefit from your leave vote” and for three years not one of you has given us an answer that is supported by evidence. .

RP – I’ve provide a lot of evidence to support reasons to Leave, but in Return all I get back from Remainers is abuse and comments about the economy. Which rather supports the theory that Remainers are afraid of what they will lose, whereas Leaver are enthusiastic of how things will improve for them.

I would be interested to know you as an individual will benefit. Whilst, I do not support language as in the previous post the problem is that most Brexiters I have encountered have not been able to properly articulate how they or I will be any better off.