Wolfgang Streeck argued last week on LSE Brexit that the EU was a ‘liberal empire’ that is about to fall. Peter Ramsay (LSE) suggests that the EU is a very particular type of empire, one that has arisen from the political decline of the nations that comprise it, and that this explains the tortured politics of Brexit.

Wolfgang Streeck argued last week on LSE Brexit that the EU was a ‘liberal empire’ that is about to fall. Peter Ramsay (LSE) suggests that the EU is a very particular type of empire, one that has arisen from the political decline of the nations that comprise it, and that this explains the tortured politics of Brexit.

Wolfgang Streeck does the Brexit debate a service by reminding us of the imperial character of the EU. British Remainers have claimed that Brexit is all about nostalgia for Britain’s maritime colonial empire. They have conveniently forgotten that the European continent is familiar with a different tradition of land-based multinational empire. Remainers would very much like the UK to Remain a part of this type of empire.

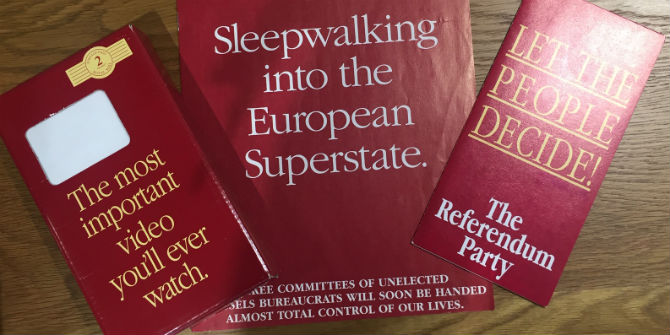

Streeck calls the EU a ‘liberal empire’ because it is explicitly committed to constitutionalism, private property, and competition. It is imperial nevertheless because one of its member states – Germany – has become hugely dominant over the others, and because EU institutions have progressively constrained the democratic process at the national level in the interests of the markets’ big players. Streeck’s account of the EU as an empire tells us much about its operations. Nevertheless, we should be wary of creating a left-wing version of conservative Euroscepticism, in which we replace bossy Brussels bureaucrats with greedy German capitalists as our image of EU overlords. It is not that there is no truth in either story, but they both tend to obscure the most significant aspect of the EU.

Francesco Albani, “Jupiter, in the shape of a bull, carrying off Europa”, Public Domain.

Francesco Albani, “Jupiter, in the shape of a bull, carrying off Europa”, Public Domain.

If the EU is an empire then it is exceptional in being a legally voluntary empire. However much German or EU officials may connive to punish Britain economically and diplomatically for proposing to leave, Britain’s right to leave is not contested in Berlin or Brussels. Rather it is in London that Britain’s right to leave is bitterly contested by a British ruling class that is fighting to Remain. If Germany has acquired the position of an imperial hegemon, it has not been by conquest or through an overweening sense of national destiny or racial superiority but rather by default, a result of the weakening of national loyalties within all of the EU’s member states.

The EU’s liberal empire is a type of government improvised by national governing elites that are reluctant or no longer able to rely on the political authority provided by democratic politics. Instead of the nation within, those governing elites look outwards to supranational intergovernmental arrangements for their authority.

It is this peculiar characteristic of the EU’s ‘liberal empire’ that explains the tortured political process in Britain following the Brexit referendum. The electorate voted to ‘take back control’ of politics and the state. In response, the bulk of the political class has been united with the civil service, big business and academia in a shared determination to resist that. The British elite prefers intergovernmental collaboration to assertions of national sovereignty. Its preference for this way of governing is so ingrained that the government has been unable to imagine adopting a robust negotiating position with the EU, and even the weak negotiating efforts of the executive have been relentlessly, and very publicly, undermined by Parliament and other politically influential figures. The effect has been to create a situation in which the options now available to the UK are so unattractive that a sense of emergency can be manufactured. In this climate, it might be possible, one way or another, to nullify the effect of the original vote to Leave. While, as Streeck argues, the German hegemon and its ally France have an interest in making the British people pay a high price for daring to defy the EU, their most effective ally in that endeavour has been the British elite itself.

The British ruling class finds in the EU an effective and attractive way of asserting its interests. And this is so even if Germany is the major gainer from the arrangement. The British elite’s repulsion from the claims of the nation is much stronger than any downsides it may experience from playing economic second fiddle to Germany. The EU is a voluntary empire made up of states that are in denial of their national character: in denial of the fact that the state’s authority derives from the political nation.

This turn by Europe’s ruling classes against the nation has transformed the terrain of politics in Germany’s ‘liberal empire’. So Streeck observes of Brexit, that in so far as the decision to leave the EU ‘was driven by nationalist…concerns, it may amount to a historical mistake’. The reason for this, he suggests, is that Britain is likely to lose international influence in Europe and the world while France will gain what the UK loses. His prognosis may be right but, as any observer of the Brexit debate will have noted, it is British Remainers who have repeatedly bemoaned this likely loss of British international influence resulting from Brexit. As Richard Tuck has shown, the case made in the 1960s for the UK joining the European Economic Community was dominated by concerns over how to maintain Britain’s global influence as the British Empire declined. Similarly, contemporary Remainers reject nationalism, the better to ensure Britain’s global influence. The laughable post-Brexit fantasies of the UK’s current Secretary of Defence only underline the fact that Leaving the EU will radically limit Britain’s remaining imperial ambitions. For this reason, Brexit is welcomed by true internationalists the world over.

The point to grasp is that the ruling classes of the EU’s former imperial states have stopped trying to project their influence at home or abroad by mobilising nationalism. Instead, they do it through participation in the supranational empire of intergovernmental cooperation and by opposition to the alleged nationalism of others (particularly of Russia and of their own populations).

Streeck declares that the liberal empire is ‘about to fall’. He points to the EU’s current evolution towards still more authoritarian and now militaristic politics, driven by tensions that may yet bring it down. So far, only the populist right has really understood the distinctive aspect of the EU’s liberal empire – the denial of the nation by the imperial ruling classes of Europe. Democrats and internationalists urgently need to catch up. Against the claims of imperial cosmopolitanism, we need to reinvigorate the idea of the nation as the site of the authority of the people and of solidarity with the nationhood of others. Against the identity politics of both the populist right and the woke left, we need to popularise the idea of the people as a citizenry of self-determining persons.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Peter Ramsay is Professor of Law at the London School of Economics. He will chair Wolfgang Streeck’s lecture ‘Taking Back Control? Brexit and the Future of Europe’ at LSE on Friday 15 March in the Sheikh Zayed Theatre at 6.30pm.

Good post. Benign paternalim has been replaced by opportunistic kleptocratic-exploitative despotism within the framework of the corporatist globalisers’ agenda. Brexit as political theatre is an educational-pedagogical performance for all the world to see. This time, the English and the Welsh are offered the opportunity to come off age politically. If they fail to meet the challenge, it will be up to the continental Europeans to take it up, or acquiesce and accept a new, globally organised, kind of feudalism.

The EU is merely the product and harbinger of globalisation as we know it now in the 21st century. An entire ruling class made up of technocrats, a smattering of old-school elites, and businessmen ruling as governors of nowhere instead of leaders of somewhere. There can be no happy ending from the very detachment and ignorance of the ruling class from the people they ostensibly derive democratic legitimacy from, i.e. their very own voters and constituents who are absolutely in their right to wish for putting country and individual nationalism first over mindless and exploitative supranationalism. Whilst it is by no means the only European country with such a political crisis of confidence and national identity, the UK is by far suffering the worst for it and it is increasingly likely that the final dissolution of the Union will happen in our lifetimes.

One of the big problems with supporting a rise in nationalism is that nations are not neatly contained in states in Europe. Most EU countries have separatist movements especially in newer states like the UK.

Looking at the UK in particular we have Northern Ireland where a big chunk of the population opt to have the passport from another country and an increasing number want to leave the UK.

In Scotland, the UK government wrote to every home warning that a vote for independence would put Scotland’s EU membership at risk.

In both Scotland and Northern Ireland there is a bigger support for remaining in the EU than there is in the UK. I think the chance of our Union surviving more than another decade or so is very low.

To be fair many Brexiters do also support the breakup of the UK which is the logical extension of their position. But I’d be very cautious about the actual power England on its own would have, which would be a country with a GDP smaller than Italy.

Good point here that once the genie of nationalism is unleashed, it would not necessarily stop with the existing member states of the EU.

Each of these states is an amalgam of rival component nations. In the UK we think of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. I am no expert on Continental Europe, but I know of problems with Catalans and Basques in Spain, Flemings and Walloons in Belgium, and Northern Italians versus Southern Italians. These regions are all co-ordinated by the EU’s Committee for the Regions of Europe.

Once centrifugal forces prise the nations of the EU apart, why stop there? The various regions within the 28 existing nations would start asserting their authority as well.

“Most EU countries have separatist movements especially in newer states like the UK.”

How, exactly, is the UK “a newer state.” Even if you date it from 1801 (when Great Britain, founded in 1707) incorporated Ireland into the Union, creating the “United Kingdom,” there is no state in Europe with an earlier foundation date. even Switzerland — a long-established entity — constitution dates from the 1840s.

Nothing new about the UK.

The UK was founded in 1707. Making it one of the oldest nation-states in the world. It’s older than every nation-state in Africa, North and South Africa.

Academic rants need more than clever rhetoric, they need, above all references that are defendable/or not. The very first paragraph here questions that need to be validated. It states that Remainers were nostalgic about British Colonialism – (please provide quote/evidence). It is very clear that it is the Brexiteers who continue to think that the UK is the power it was in those colonial times and can command the respect with the rest of the trading world as it moves into Brexit+, WTO rules, etc.

The EU is most definitely an economic and political powerhouse (one the UK has decided to side-line itself from) but it is not some empire, as you say.

It is not the ‘ruling class’ – an unfortunate phrase – that continues to be the threat to democracy, Brexit being a very clear example. The other ‘classes’ drove the vote with or without ignorance. The next parliamentary vote will have little to do with any of this- it will be about Theresa May trying desperately to find face.

This is further evidence of the hopelessness of the anti-EU crowd that after failing with their accusations that the EU is either the “soviet union” or the “nazi empire” it is now attempting to insult the EU because of its commitment to “constitutionalism, private property and competition”

“Streeck calls the EU a ‘liberal empire’ because it is explicitly committed to constitutionalism, private property, and competition.”

I really though enjoyed the author’s definition of “voluntary empire” just goes to show what kind of semantic extremes an author might be willing to go just to justify his or her absurdism. The levels of absurdity here are quite unique rendering the very definition of “empire” absurd, as empires are neither “legally voluntary” for the subjects nor politically and legally equitable and representational.

“If the EU is an empire then it is exceptional in being a legally voluntary empire.”

It should be noted that the EU is not simply a voluntary organisation but an institution that offers its members equal representation in all aspects of its governance, in the EU Council, the Commission, the ECJ, the Council of the EU. And that prior to this arrangement we had actual empires dictating terms to the nation-states who had no mechanism to participate in the decision-making policy of whatever Empire or nation was the Hegemon and in charge.

‘Voluntary empire’ is absurd. However the absurdity is not in my description of the EU’s form of government but in the EU’s form of government that I am describing.

For states to voluntarily relinquish their sovereign responsibilities to an intergovernmental process that a) undermines the real source of those states’ political authority – their political relation with their own peoples; b) facilitates the domination of one of the states (Germany) over the others – notwithstanding its own attenuated domestic political authority and entanglement in the intergovernmental process; and c) nonetheless allows those states to insist on their sovereignty when it suits them and they have the clout to do it (esp France), is indeed an absurd way to govern.

It arises because governing classes are trying to rule without the authority of the people. Lacking real authority they are constantly trying to pass responsibility off to EU institutions made up of governments that like them lack real political authority or to Mutti Merkel herself who has no more either. The increasingly chaotic impasse in British and European politics is the result.