Commentators (and Theresa May) have talked up the identity divide between anti-Brexit ‘cosmopolitans’ and those who support leaving the EU. But the concept of ‘cosmopolitanism’ is more elastic than these polarised identities suggest, says Eleni Andreouli (Open University). For some, it is possible to reframe Brexit as a chance to embrace a more global identity by establishing new trade links with the rest of the world, for example.

Commentators (and Theresa May) have talked up the identity divide between anti-Brexit ‘cosmopolitans’ and those who support leaving the EU. But the concept of ‘cosmopolitanism’ is more elastic than these polarised identities suggest, says Eleni Andreouli (Open University). For some, it is possible to reframe Brexit as a chance to embrace a more global identity by establishing new trade links with the rest of the world, for example.

It is commonplace to argue that the UK has a fraught relationship with the European Union. While the UK is a member of the EU and, as such, it has taken part in its political and economic integration project, this has felt half-hearted. The UK, for example, has opted out of some key EU initiatives, such as the single currency and the Schengen treaty, and it has generally been reluctant to engage in deeper European integration.

In that sense, the Brexit vote to leave the EU may be understood as evidence of the country’s long-standing Euroscepticism. Euroscepticism in the UK is much more entrenched than in the rest of Europe (Matthew Goodwin and Caitlin Milazzo, 2015). It is indeed the case that the British feel less attached to the EU compared to the EU average (as is shown in the 2016 Eurobarometer survey (pdf), for example). And, as noted by John Curtice in his review of British Attitudes surveys, Post Brexit, Britain is more Eurosceptic than ever.

How could this be explained? In European integration literature, three factors have been identified as driving support for the EU: (i) utilitarianism (support is contingent on a calculation of costs and benefits of membership, with members of the higher socio-economic classes or countries that receive more EU funds, having more to gain and, thus, being more supportive of the EU); (ii) cue-taking (support for the EU depends on citizens’ positive or negative views of domestic politics); and (iii) identity (support for the EU relies on citizens’ attachment to a sense of European identity).

As a discursively-oriented social psychologist, I focus on the latter of the three. I see identities as part of systems of lay ‘common-sense’ knowledge through which citizens understand and navigate the world around them. Like other social psychologists before me have stressed, identities are political projects that define ‘us’, ‘them’ and ‘our relationship’ (Xenia Chryssochoou, 2003).

Importantly, identities do not only represent how we see the present, but also how we imagine the future; rather than ‘things we have’, identities are better understood as projects that guide social and political action (Stephen Reicher, 2004). It makes sense then that identities are neither singular nor fixed; their meanings are socially elaborated, argued upon and debated.

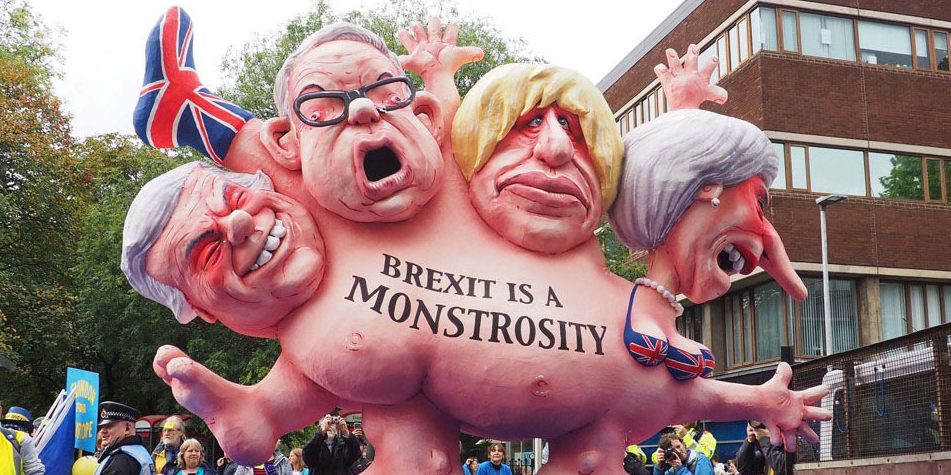

In 2016, the UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, stated that “if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere”. This statement was intended to show that the PM is sympathetic to the grievances of the ‘left behind’, or the so-called ‘losers of globalisation’, labels given to the working classes that have been hit by de-industrialisation and adversely affected by the economic globalisation of the past few decades. These are considered to be the ‘typical’ Brexit voters, as identified in relevant literature (e.g. Matthew Goodwin & Oliver Heath, 2016; Sara Hobolt, 2016). By taking a stab at cosmopolitans, Theresa May acted as an ‘identity entrepreneur’. She sided with ‘the people’ against the ‘metropolitan elites’, a dichotomy that has too often been used to explain the differences between Leave and Remain supporters in Brexit debates.

In an effort to move beyond such simplistic and polarising schemas and to understand citizens’ perspectives in more nuance, in my research I studied how the notion of cosmopolitanism features in lay discussions about European and British identities in the run-up to the referendum in June 2016.

One of the themes that emerged in my analysis of focus groups was ‘cultured and cosmopolitan Europe’. Unsurprisingly perhaps, this theme was more salient in the Remain-leaning, younger and London-based participants of my study. Here is an example from the account of one of the participants when they were asked what comes to mind when they think of the word European:

“…cosmopolitan, kind of arts, history, gourmet food, culture of food and fine food… Obviously, that’s all the kind of high stuff, but it’s what springs to mind initially.”

Below is another extract from a different participant expressing the view that Brexit will be an international embarrassment because it shuts Britain away from the world:

“I feel a bit embarrassed as well, like from a world point of view. I think I feel a bit like, great, we’ve said to the world we just want to shut ourselves off and be a little island.”

In these extracts, Europe is represented as cosmopolitan against the backwardness of Brexit. In a way, Brexit Britain is ‘Orientalised’ (Edward W Said, 2003) as a backward country in the margins of modernity.

Contrasting this theme was the theme of ‘Little Europe/Global Britain’, which represented Brexit as a cosmopolitan project against the insularity of the European Union. Below is an exemplary extract from a focus group with Leave-leaning participants:

“I don’t see it [Brexit] being an issue, it opens the UK up to other countries we can trade to instead of being stuck in Europe… I think we’re being held back, you know, because of Brussels we have to have permission to do – to be told what to do.”

Interestingly, Brexit, commonly cast as a nationalistic project, becomes here a cosmopolitan project. Britain, in this account, is bigger than Europe, and the EU is seen as holding the country back from pursuing its cosmopolitan potential. This representation of the EU rests on a vision of post-imperial Britishness, whose key feature is British exceptionalism defined through its opposition to Europe and the EU (Chris Gifford, 2015).

Two points can be drawn by the above: first, the meanings of cosmopolitanism and how it relates to Britishness and Europeanness shift and change depending upon which political projects these identities are attached to. On the one hand, cosmopolitanism may be linked to a non-British ‘cultured’ Europe, which puts Brexit Britain in the margins of the European cultural core. On the other hand, in accounts echoing images of Britishness as an imperial identity, Europe is constructed as limiting Britain’s global aspirations.

Second, values – such as cosmopolitanism – are not fixed, but can be argued about and stretched. Indeed, they may be stretched so far that they contain ideas seemingly at odds with the very ideals that they represent – such as restricting European international cooperation under a narrative of ‘cosmopolitan Brexit’ (Eleni Andreouli, David Kaposi & Paul Stenner, 2018).

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Eleni Andreouli is Senior Lecturer in the School of Psychology at the Open University. She obtained her PhD from LSE.

I like this thoughtful post. I must say it has always puzzled me why people from the Commonwealth are not part of the’Free Movemen of People. In the Windrush affair, people who have given so much to this country and were invited here in the first place,were deported without much care to their circumstances. I.I think it unfair that people from the Commonwealth cannot have the same freedom to be in this country as people from Europe.when it is they who have helped give Britian it’s place in the world.

There are racists in Britian as they are everywhere else,but i do not think people who voted Brexit are any more racist tahn those who voted Remain . Some Remain voters all voted to keep Britian European.which they associate with sophistication..and Western culture..

I’m with you on that Mrs Cheek – one objection to current EU FoM is that it prioritises Austrians over Australians, when I (and I suspect a majority of the UK) would prefer the reverse if we had any say in the matter. Equally, I think you’re right on the money with some Remain voters having a “keep Britain European” motivation, of shutting out ‘more foreign’ countries by importing Eastern Europe instead.

I can’t see Rory Stewart ever passing for a Conservative leader, though: what appeal he does have is almost all to the Guardian-reading end of the spectrum. Lib Dem leader, perhaps, or even a new Blairite Labour leader, but not conservative in any sense!

I think Rory Stewart would be a good prime minister.. He would calm the country down . He comes over very well.in a quiet way. A diplomat,with a world upbringing and the sort of person who will getall sides to believe that they are winners.