Marzia Maccaferri (Goldsmiths, University of London) looks at how the press covered the referendum campaign and in the process revived notions of the ‘Anglosphere’ and British exceptionalism.

Marzia Maccaferri (Goldsmiths, University of London) looks at how the press covered the referendum campaign and in the process revived notions of the ‘Anglosphere’ and British exceptionalism.

Historically, British public opinion has always turned to the newspapers at times of national significance, and the Brexit vote confirms this tendency. The traditional press, bolstered by online media, remains the principal indicator of public discourse and still plays a crucial role.

Analysing editorials and comments during the EU referendum highlights a process of recontextualisation of the material and immaterial borders between Britain and Europe. A new ideology which reproduced historical arguments – as well as reinterpreting dated clichés – was formed, and created a new and hierarchical discursive order.

History was the glue that bonded together opposite discourses and concepts, reconceptualising historical categories and playing a pivotal role not only as the point of departure, but concluding its parabola as the place of destination. Both the Leave and the Remain arguments revolved around the historical ‘exceptionalism’ of the British political tradition: from the nostalgic comments of the Telegraph and Spectator to the rationalistic pro-EU City-centric editorials of the Financial Times, or London-centric comments of the Guardian, the Brexit discourses developed in the press during the referendum campaign applied ‘history as ideology’. Do these shifts (re)create a nationalistic identity based upon a new ‘post-imperial exceptionalism’ and the Anglosphere’s hegemony?

Britain and Europe: a troubled relationship

The relationship between Britain and Europe has mostly been regarded as cautious and parochial. On the one hand, the self-representation of Britain (most often meaning England) as the ideally liberal and democratic nation first shaped by the Reformation, the Industrial Revolution and later framed by Victorian values created a national identity clearly separate from the Continent. On the other, this Victorian sense of ‘splendid isolation’ was extensively reinforced by the experiences of the two world wars.

The Suez crisis played a salient role in the post-imperial UK-Europe relationship. From 1956 onwards, Britain was immersed in a long and exhausting debate on the ‘decline of the nation’, and dallied once again with a newly materialised ‘splendid isolation’. It is within this matrix that we can trace the roots of contemporary Eurosceptic and Europhile discourses. As Oliver Daddow has argued, the UK’s Eurosceptic discourse appeals to the nation’s sense of pride and its imperial past, its military record and its parliamentary history: Britain as a world power and a beacon of democracy. It plays upon wartime efforts and achievements. The Europhile discourse also calls on history to support its narrative, but using the opposite argument: it is the history of Europe and its economic success that together encourage Britain’s involvement. It is clear that both discourses formulate their constructions and arguments on the back of competing perceptions of history: they have been built upon history, ‘depend on’ history, but they problematise a different past.

Historical narratives are constantly discursively (re)constructed and, according to Reinhart Koselleck, dominant discourses and narratives tend to relativise, deny, reformulate or even bury dramatic events. During the referendum campaign, some discourses lost their primary function and became a completely new ‘signifier’. This selective reproduction of historical narratives and discourses has decontextualised some concepts, and rearranged and reshaped other elements in order to craft (new) strategic hierarchies and ideologies.

The historical discourse of Brexit in the press

In framing the role of newspapers (see Table 1), it is important to distinguish the short-term role played during the referendum campaign – which mirrored a conflictual rather than collaborative relationship with the EU – and the long-term cumulative influence exercised by the media. Well before the campaign began, the public opinion had been primed by the Eurosceptic media. In addition, the British have a very limited knowledge of European history.

| Pro-Leave (* with editorial stance) | Pro-Remain (* with editorial stance) |

|---|---|

| Daily and Sunday Telegraph* | Financial Times* |

| Sunday Times* | Guardian and Observer* |

| Daily Mail* | The Times* |

| The Sun* | the I |

| Daily Express and Sunday Express* | Economist* |

| Spectator | New Statesman* |

| Prospect* | |

| Mail on Sunday* |

During the campaign the Leave camp was prominent, employing a compelling narrative capable of constructing a proactive argument for leaving the EU via the general claim of ‘regaining control.’ This forced the Remain media to pursue Brexit arguments and the anti-Brexit camp patterned a ‘negative’ discourse mostly focused on warnings about the economic implications (so-called ‘project fear’). But he result reinforced the main Brexit arguments and, ultimately, contributed to the prominence of the macro narratives of auto-determination and control, sovereignty and security, sidelining social, cultural and civic issues.

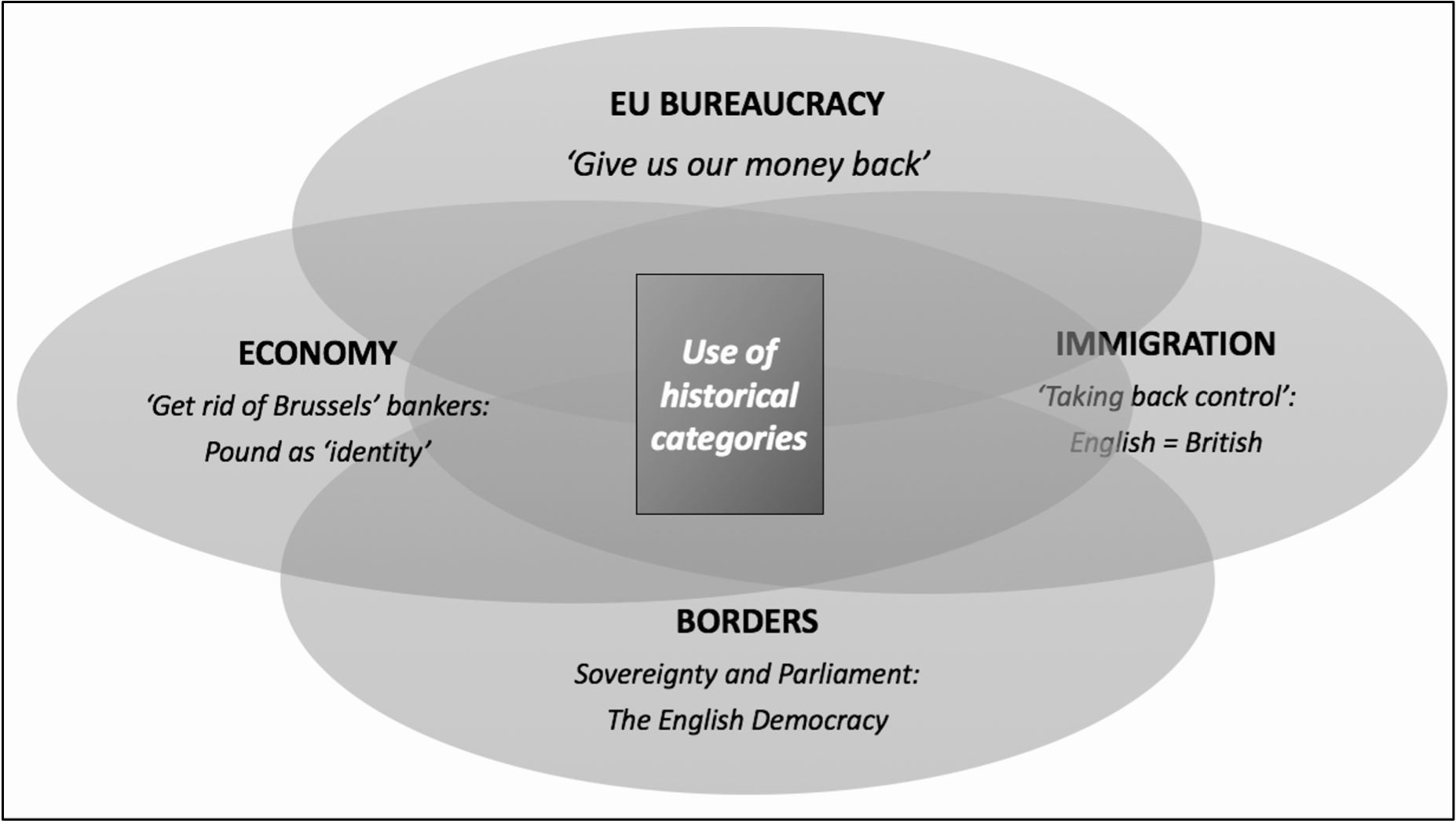

The main arguments, both for Leave and Remain, revolved around immigration, economy, EU bureaucracy and borders. Each topic was identified with a catchphrase which was constantly reconceptualised, leaving complexity and perspective behind. The selective reproduction of meaning ‘translated’ the central topics of the discourse into a new matrix of interchangeable concepts. Each of them could at the same time be discursively linked with immigration and the economy, EU bureaucracy or the issue of borders (see Figure 1). They seemed to ‘sit comfortably’ with each other, to the point that it can be hard to find structural differences between the pro-Remain press and the Leave media.

For example, the concept of ‘taking back control’ or the variant ‘getting rid of Brussels bankers’ – depending whether more emphasis is put on the economy or immigration – can also be associated with the supposed EU oligarchy and the need to reintroduce ‘borders’. At the same time, references to ‘borders’ emphasised not only the action of ‘taking back control’ from a ‘corrupt’ (The Daily Telegraph, 24 June 2016), ‘failing’ (The Guardian, 6 March 2016), ‘alien’ (The Times, 22 May 2016), ‘oppressive’ (The Times, 21 June 2016) and ‘antidemocratic’ Brussels (The Spectator, 18 June 2016), but was reminiscent of the historical category of ‘British exceptionalism’, primarily understood as ‘sovereignty’ and ‘Parliament’. On the other, it also hinged upon the historical concept of ‘splendid isolation.’ The British pound was used as a byword for national identity (The Economist, 18 June 2016).

Brexit and anti-Brexit discourse were both fashioned around different interpretations of history: ‘British splendid isolation’ in contrast to ‘British political tradition.’ However, both fronts stressed the discursive power of British ‘exceptionalism’. At stake were material borders (for Leavers) and intellectual or historical borders (for Remainers) and their relationship with ‘English democracy’: a democracy that had to be restored outside Europe for the former, or a system that had to be reinvented by leading Britain inside Europe for the latter.

The rise of the ‘Anglosphere’

Three paradigms emerged:

- a revolt against globalisation;

- a clash between the so-called baby-boomer generation and subsequent generations;

- Brexit as an expression of Englishness, which is rooted in the deindustrialised North, in the relative rural poverty of the south-west and in the suburban lower-middle classes of the once-great cities.

This puzzle acquired a ‘populist’ character: Brexit is manifestly a discourse against multiculturalism and in favour of English neo-nationalism.

A different interpretational framework for Brexit can be traced back to the rise of the ‘Anglosphere.’ It returned as a central concept in the British political culture of the 1980s, and gained momentum during the New Labour era as an alternative to the European Union. The Anglosphere’s potency as a geopolitical organising ideal was in contrast to the lack of a united European foreign policy. The Anglosphere’s potency is largely ideological, not geopolitical. Its function is an imaginary horizon; it registers nostalgia, but also energy. Crucially, from the perspective of Brexit discourse as it was reconceptualised during the referendum campaign: the Anglosphere evokes a way of articulating a new national narrative interrelated with the past. In this recontextualisation, even the legacy of the Empire seems to be freed of any sort of responsibility or guilt: a kind of ahistorical idea of the British Empire arises.

In one of his last articles, the historian Hugh Seton-Watson argued that the reason for the reluctance to accept a ‘dual identity’ (i.e. British and European) lay in ‘the prevalence in a large part of the British cultural élite of a hangover from Empire in the form of a guilt complex towards the peoples of Asia and Africa.’ Now, within the Brexit discourse, guilt associated with the imperial legacy seems to have disappeared and been replaced by (supposedly) positive aspects of the British political tradition, such as the principles of free trade, the rule of law or parliamentary democracy. This process of re-engagement adopts a strictly English reading of the past.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Marzia Maccaferri is an Associate Lecturer in Politics at Goldsmiths, University of London.

I think the article fails to recognise a further form of English exceptionalism on the Remain side, namely that only in the UK do the laws of supply and demand not apply. So according to the Europhiles, the increased rate of EU immigration in the years preceding the referendum had no effect on salaries in the UK nor on house prices or rent. Yet subsequent to the referendum, the rate of EU immigration has slowed and the ONS is able to report that salaries are rising in real terms particularly among the lower paid and that house prices have steadied.

I am not quite sure what is meant by ‘Anglosphere’, but the article has failed to mention the increasing international prevalence of the English language in recent years which necessarily changes this countries perception of itself.

The historical narrative in this article is uncomfortable. It chooses to go as back as far as the Victorian period but then no further back than that. If we wish to look back in history then we should look at English Empiricism in comparison to Continental Rationalism as represented by the discourse between Hobbes and Descartes. The current situation can be seen as a continuation of a long tradition wherein Britain takes a utilitarian stance against continental idealism. At the end of the 18th century and the first part of the 19th century Continental Europe suffered a wave of revolutions which entirely passed Britain by. British pragmatism prevailed.

I voted leave……..simple I do not want ever closer union ie super state, no flag, no anthem, no army navy or air force ho and Germany any where near Frances nukes,,,…..I am 70 years old voted to join common market good idea but not what we have now or where EU is going no thanks ,,,,not just money