The government wants to bring the country together around its version of Brexit. It believes that it has the potential to return hope to the majority of citizens who express various forms of pessimism about the effect that Brexit will have on their country, their families, and their lives. But are citizens believing that reconciliatory scenario, asks Sarah Harrison (Electoral Psychology Observatory, LSE)?

The government wants to bring the country together around its version of Brexit. It believes that it has the potential to return hope to the majority of citizens who express various forms of pessimism about the effect that Brexit will have on their country, their families, and their lives. But are citizens believing that reconciliatory scenario, asks Sarah Harrison (Electoral Psychology Observatory, LSE)?

As the country is getting ready for a December General Election which will, yet again, focus on parties positions’ on Brexit, even in the most optimistic of scenarios suggest that the Brexit saga will continue, either with a further renegotiation of the withdrawal agreement, a process of rescinding Brexit, a confirmatory referendum, and/or the start of the transition phase and of the negotiations of the EU-UK permanent relationship. The government has clearly framed its proposed revised Withdrawal Agreement as a chance to bring the country together around what it considers to be a compromise. It believes that this process has the potential to return hope to the majority of citizens who express various forms of pessimistic outlooks about the effect that Brexit will have on their country, their families, and their lives. But are citizens believing that reconciliatory scenario?

As our team showed in June, levels of hostility between citizens surrounding the Brexit question and beyond have reached traumatic heights. We showed that far from being limited to an expression of suspicion towards politicians and institutions, citizens have started to harbour resentment towards one another in ways that threaten the most basic mechanisms of solidarity, communication and goodwill that are critical to the function of any democratic society. We notably identified an increasing trend that suggested many citizens to begrudge having to pay taxes that would shield others from the economic and social consequences of a Brexit they did not choose, or for those who voted for it, for a Brexit that some citizens might help frustrate.

In this article, I consider a further crippling consequence of Brexit fractures and hostility on everyday life by reporting findings from the third wave of our Electoral Psychology Observatory – Opinium Hostility Barometer. In this edition, we focus primarily on how citizens predict that Brexit will affect their everyday life and behaviour – from family plans all the way to consumption and banking.

A pessimistic vision of future economic and personal behaviour

When we asked this particular series of questions in August, there were still strong suspicions of a ‘no deal’ outcome. There is a legitimate question as to whether the possibility of the current deal would correct the pessimism that voters perceived at the time of the survey, but for all practical purposes, it mostly seems that the proposed deal merely satisfies those who were willing to leave without a deal anyway without, in any way, reassuring those opposed to Brexit in the first instance.

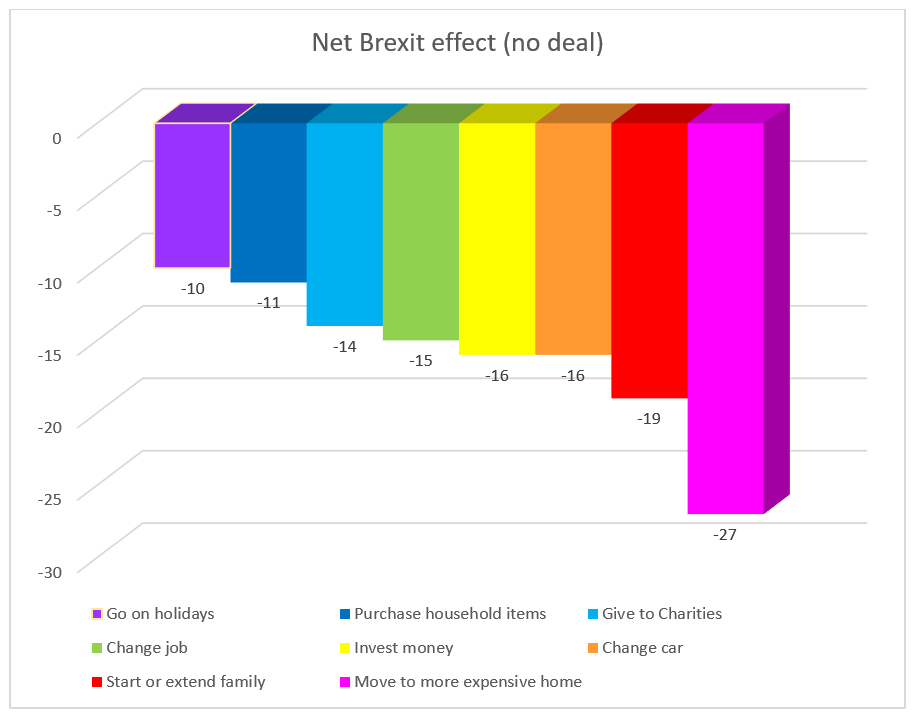

In that context, the net balance between those who felt more likely or less likely to engage in basic patterns of economic or personal behaviour in the light of a likely no deal exit on 31 October was as shown in the figure below.

Those negative net differences are very significant. They confirm a gloomy outlook in both economic and lifestyles contexts, a predicted future where citizens plan to curtail and restrict their behaviour in the next 12 months. In fact, those figures echo existing behavioural trends observed on critical economic fields such as the housing market.

Indeed, the government’s hope would be that if a deal resolved uncertainty, the projected behaviour of citizens might be less dramatic, but the understanding of experts is that even if the withdrawal agreement were to be adopted without any modification, it does not settle any of the significant questions pertaining to the long-term status of the UK’s trade with the EU, with any other part of the world, or indeed, the future economic and bureaucratic conditions that would be faced by all the major economic sectors that would be impacted by Brexit after two years of economic transition – from fisheries to banking, from research to the pharmaceutical industry, and from SMEs to direct foreign investment and the car industry. In fact, observers were quick to note that small businesses in Northern Ireland would likely face major new red tape if the withdrawal agreement is adopted, whilst others underlined that the possibility of a cliff-edge Brexit would simply be delayed till 2021.

In other words whilst the possibility of a deal might lower the risk of immediate panic the structural nature of the gloom expressed by respondents – indeed, the hopelessness of many – is most unlikely to be tied in any way to the nature of an agreement being reached, given the remaining fracture between those eager to obtain Brexit in any condition and at any cost on the one hand, and those eager to avoid it at any cost and in any condition on the other hand, with very few voters genuinely trapped in between those clear cut positions.

This is all the more emphasised by the sequential nature of negotiations which have been organised in such a way as to ensure that any short-term relief in a situation of uncertainty only paves the way to the next sequence of unpredictability.

Fundamentally, the possibility of a withdrawal agreement being voted by Parliament – regardless of whether it is on the Prime Minister’s terms, or with conditions that would anger government, such as a Confirmatory Referendum or Customs Union condition – have not fundamentally affected the balance of hope and hopelessness in public opinion.

The immense majority of those who rejoice at the idea of a deal having been struck between the UK and the EU are those who were in any case, sufficiently confident in the supreme importance of leaving the European Union to be optimistic about the country’s future even in the event of a cliff-edge exit. By contrast, the immense majority of those who expect their future economic and personal behaviour to be negatively affected by Brexit will remain deeply unconvinced by any minoring of the Brexit stakes – be it what many will see as the “hard Brexit deal” negotiated by Boris Johnson, the buffer of a customs union amendment, or the glimmer of hope of an ultimate Final Say Referendum.

Indeed, both demographically and psychologically, those who believe that Brexit is a catastrophe also happen to be those most likely to enact some of the major economic and personal plans that we tested – from moving to bigger houses to changing jobs and starting a family. Any inability to convert them from worry – or indeed hopelessness – to enthusiasm and hope would invariably have a disproportionately negative effect on the economic, social, and demographic reality of the country for years to come.

Notes: Data from the EPO-Opinium Hostility Barometer Wave 3. Fieldwork conducted by Opinium https://www.opinium.co.uk/. Field dates: 23/08/19 – 27/08/19. Sample: 2,006 UK Adults. Weighting: Data has been weighted to nationally representative criteria. The Electoral Psychology Observatory (EPO) reports findings from their most recent edition of their “Hostility Barometer” run in collaboration with Opinium. The Hostility Barometer is an integral tool that enables the EPO team to measure and track the evolution of electoral hostility within the remit of the ELHO project funded by the European Research Council. The barometer is conducted on a monthly basis in the UK and will also be run in the US later in the year.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image CC0 Public Domain.

Sarah Harrison is Assistant Professorial Research Fellow in Political Science in the Department of Government at the LSE, and Deputy Director of the Electoral Psychology Observatory.

The basic problem people have in deciding IN/OUT is how the future of the EU will effect the UK against that of how Brexit will effect the same. People are often happy with the status quo as it involves little decision making.

It requires a strong person to alter their way of life when it appears not to have a problem.It is easier when a person has made many decisions in the past and the general public have had things easy for the last few decades, hence the quandary. To put it simply, I would rather be a Meerkat than an Ostrich.

Being a free minded Meerkat I will not run down the hole to safety but this time challenge the status quo with my wanting to leave the EU. I would prefer an arrangement that would give us complete freedom from the EU before leaving but I also have faith in the leaving without a deal and organizing Trade, Defense and mutual cooperation afterwards. A lot of which has already been done.

You may like to think you’re a Meerkat, but from your latter comments I would definitely classify you as an ostrich.

Austerity has stagnated the economy, both in the UK and in the EUrozone institutionalised austerity of the completely unnecessary, arbitrary 3% limit on public purpose. This is all in the context of a slowing and fractious global economy. All this before we even mention the on going supertanker style car crash of climate chaos.

While your team may consider that Ireland may be a ‘winner’ under the most recent Boris-EU deal; there appears to be a resurgence of tension among Loyalist paramilitaries, particularly the UVF and Ulster Resistance which necessitated a response from Arlene Foster’s DUP, prior to her meeting with Boris Johnson (see my letter in The Guardian of 23/10).. Similarly there are reports of increased number of Orange ‘walks’ in Glasgow which is interpreted as a fear of alienation from the Union. A backlash against Catholic communities both in Scotland and enclave communities in NI may be unanticipated outcomes as a result of Brexit.