The UK’s decision to leave the European Union raised the prospect that other member states could follow suit. But are any other states likely to give up their membership? Markus Gastinger (University of Salzburg) presents an ‘exit index’ that captures how likely EU members are to leave, and finds it unlikely.

Ever since the United Kingdom decided to leave the European Union in June 2016, one question has been on the minds of many Europeans: which other member states could leave the EU in the years ahead? In fact, one argument among Brexiteers in the run-up to the referendum was that the UK needs to break free from the EU as a ’failing political project’, a mantra repeated by Leave supporters to this day. But how likely is it that the EU will fail?

In a recent paper, I argue that there are essentially two scenarios in which the EU could collapse. The first entails all EU member states agreeing – unanimously – to change the Treaties and dissolve the EU. This is, perhaps self-evidently, never going to happen since there will always be states opposing this course of action (e.g. Luxembourg). The second scenario is the EU being hollowed out by successive – but individual – exits of member states, which each state can decide on a sovereign basis within its own domestic political arena.

This second option cannot be discarded out of hand. The UK ’successfully’ leaving the EU will demonstrate that it is just that – an option for member states. In fact, many states have already been linked to future exits, as this picture brilliantly summarises. To get a better understanding of how much of a threat this really is for the EU, I develop an ’exit index’ to measure each member state’s propensity to leave the EU.

The approach underpinning the exit index is simple. I look for indicators in the social, economic, and political dimensions that help us develop a better sense of how likely future exits are. For example, in the social dimension, it seems clear that the greater the share of citizens having only a national (and no European) identity, the more plausible an exit scenario is. Economically, the share of exports going to other EU member states (and thus the value of membership of the single market) promises to be a good indicator. Politically, the share of Eurosceptic MPs goes, among other factors, into the exit index.

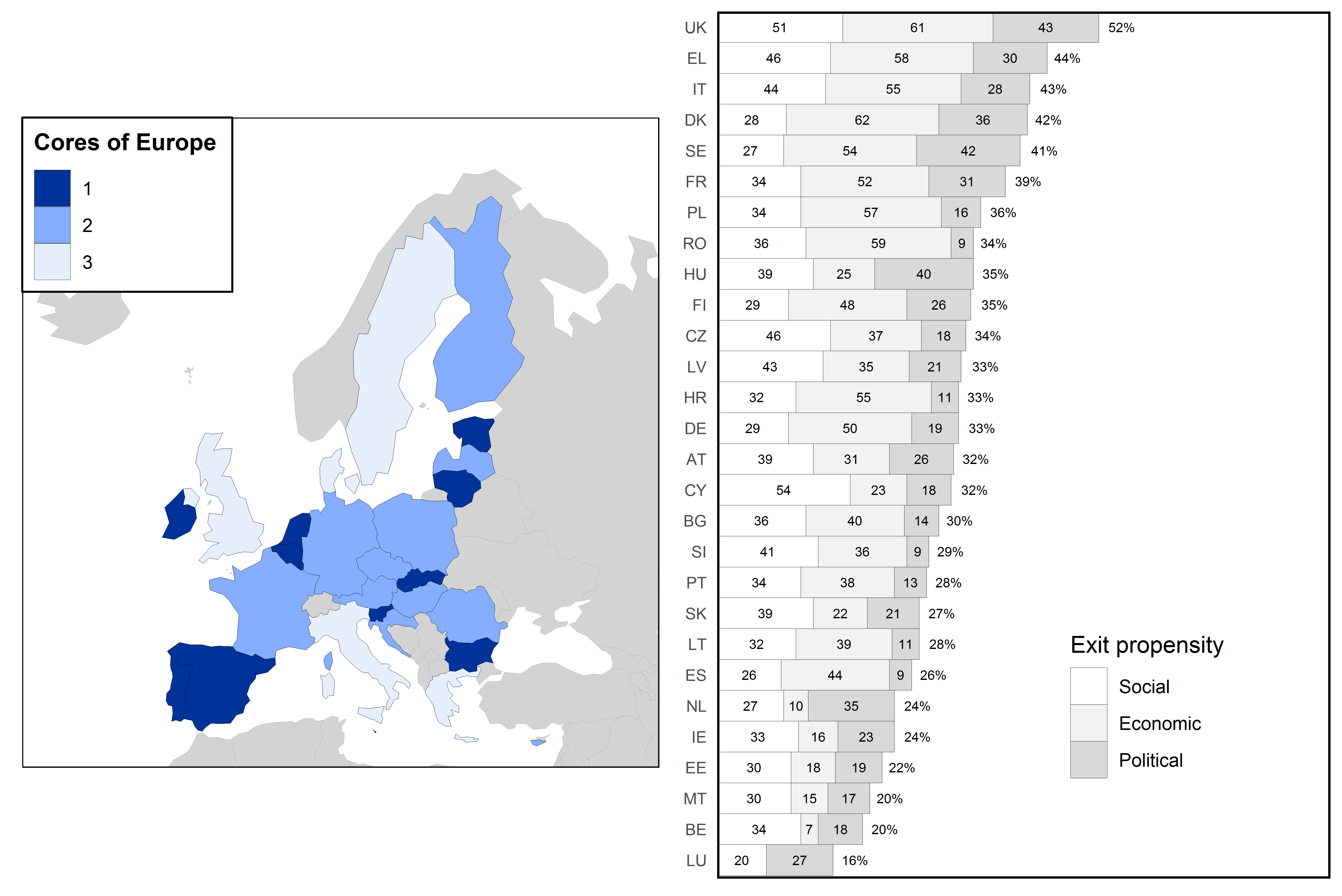

My findings can be summarised in two figures. Figure 1 shows the situation before the Brexit referendum (so around 2016). As can be seen in the table on the right, the UK really was uniquely positioned to leave the EU. It was also the only country ranking in the top three in each dimension individually. If we understand these dimensions as necessary conditions, where countries only leave the EU if ‘doing well’ across all three, no other member state faces a comparable risk of leaving the EU.

The exit index also allows us to define ’cores of Europe’. Core 1 states are extremely unlikely to leave the EU. Note, for example, that Ireland clearly falls into that category. Core 2 states are very unlikely to leave, but more likely than core 1 states. France and Germany, for example, belong to this core. Core 3 states are most susceptible to a leave vote. Unsurprisingly, Greece and Italy can be found in this core. However, even in core 3 the default expectation remains EU membership for all states but the UK.

Figure 1: Exit propensities before the UK’s EU referendum

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

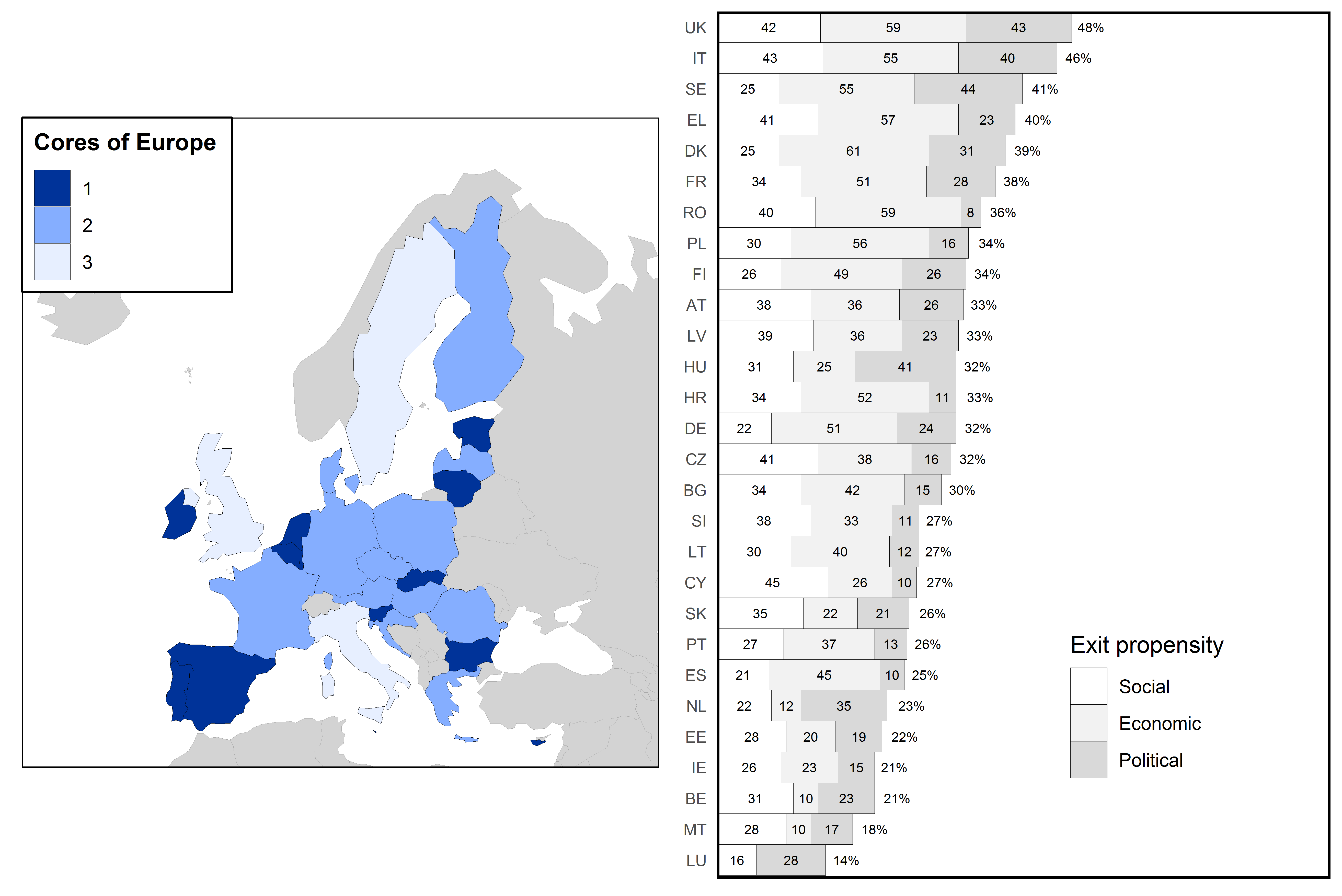

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

Figure 2 shows how the situation has changed since the referendum. These numbers also ’simulate’ Brexit by excluding the UK from intra-EU export figures. Overall, the EU has moved closer together. The only country really edging closer to an exit scenario in the past three years has been Italy. However, only 39 per cent of Italians lack a European identity. For comparison, the UK hit a whopping 63 per cent before the (narrowly won) referendum. Moreover, Italy would face massive economic adjustment costs from leaving the Eurozone.

Figure 2: Exit propensities after the UK’s EU referendum

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper

Importantly, Germany is far from abandoning the European project. Given its size and geographic centrality, it can be viewed as the linchpin of European integration. As long as Germany remains in the EU, it seems unlikely that other member states will see their national interests served by cutting ties to Brussels (and thus, to a significant extent, also Germany). France is somewhat more susceptible to an exit scenario, but the French also have a rather pronounced European identity and would face great difficulties in abandoning the euro. With France and Germany all but assured to stay in the EU, it is hard to imagine a plausible scenario where many (if any) member states would prefer to leave.

It is also interesting to note that the situation in the UK itself has changed significantly since the referendum. With 51 per cent, a slight majority of its citizens feel partly European today (compared to only 37 per cent before the referendum). Also, immigration from other EU member states is viewed in a more positive light. Today, 70 per cent feel positively about EU immigrants (compared to only 53 per cent around 2016). What is surprising then is that the share of respondents seeing a better future for the UK outside the EU has even increased slightly. One way to interpret this disconnect is that the British do see a better future outside the EU not because of issues connected to the EU itself anymore, but to finally put an end the domestic political battle that has ravaged the country ever since the Brexit referendum has taken place.

All in all, the EU is in – perhaps surprisingly – good shape with few indications of other member states following the UK’s example and trading EU membership for a more than uncertain future. If anything, the political and social fallout after the Brexit referendum had the opposite effect and brought the remaining EU member states closer together. Describing the EU as a ’failing’ political project, therefore, is a serious mischaracterisation. This also underlines that the UK will need to define a future relationship with the EU as a whole in phase two of the negotiations, which will begin after the UK has ratified the withdrawal agreement and formally left the EU.

While it is perfectly understandable that people across the UK suffer from ‘Brexit fatigue’ and want to ‘get Brexit done’, the sad truth is that Brexit will remain a major topic – on both sides of the Channel – for years to come. The most important thing is that, during this long period of hard bargaining among neighbours, everyone in the UK and all across the EU remembers that there will always be so many more things that unite than divide us. An adversarial relationship based on loose ties serves no one in the long term.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Markus Gastinger has a PhD from the European University Institute and is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the University of Salzburg, Austria. He tweets @MarkusGastinger

The article says “Importantly, Germany is far from abandoning the European project”. I live in Germany, so let me comment on that. I agree with the article’s author that Germany is not especially likely to leave the EU. But then I would probably have said the same about the UK 20 years ago. I think Germany leaving the EU is a “black swan” event which, while unlikely, is much more likely to happen than experts typically might expect. Perhaps the likelihood is more 1 in 3 than 1 in 100.

Let me speculate on reasons why Germany might in the next decade or so, leave the EU.

1. The EU has survived the Greek sovereign debt crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis, and so far does not seem to have been permanently damaged by them. But in both cases, one has the feeling that there is no satisfactory permanent solution. The Euro countries still have a common currency but inadequate coordination of macroeconomic policy. There is still no effective way of dealing with massive inflows of refugees and at the moment this is only prevented by ethically dubious attempts to prevent them crossing the Mediterannean and the deal with Turkey (which might easily collapse). So either of these crises could come back, perhaps in a worse form (imagine a French or Italian sovereign debt crisis). If either of them do, there will probably be large popular support in Germany for the idea that they are being asked to pay for everyone else or take in everyone else’s refugees, which could easily lead to a break with the EU.

2. Nobody knows how Brexit will turn out. But my guess is that any economic consequences for the UK will be limited to a few percentage points on GDP. This will mean that for most people they are hardly noticable. This would of course be grist to the mill of the more Eurosceptic part of the German population.

3. German domestic politics is not especially healthy at the moment, as is shown a. by the fact that at the moment Germany is ruled by a grand coalition which hardly anyone likes; b. the ongoing difficulty in forming a functioning governing coalition in Thüringen. The fundamental problem is the AfD. It seems to me a very real danger than, once Angela Merkel is gone, the CDU/CSU will no longer be able to resist the temptation to work in some way with the AfD, since this may be the only remaining way of forming a stable government. It is at least highly conceivable that as the price for this the AfD would force the CDU/CSU into Eurosceptic concessions, perhaps even leading to a membership referendum like the UK referendum.

This is all speculation of course. I hope readers will forgive this long contribution, which I hope shows that it is really much more complicated than just the three indicators (social, economic, political) mentioned in the article.

Dear “Alias”,

Thanks for your comments. Let me tackle them in turn.

1. I agree that the Euro and the redistribution of refugees will stay on top of the European agenda for some time. But I don’t think that Germany “paying for everyone” or taking in “everyone else’s” refugees is a likely outcome.

2. The impact of Brexit on the UK economy will depend heavily on the kind of deal that the UK ultimately strikes with the EU. But, in the paper, I actually do argue that the UK would be RELATIVELY little impacted by Brexit (the effect of a hard Brexit could still be substantial, though…). The same does NOT hold not true for some other EU member states, where intra-EU trade accounts for a much larger share of GDP. So this is fully accounted for in my exit index.

3. The political system in Germany is actually one of the strongest point AGAINST Dexit. Germany has a system of proportional representation and a tradition of coalition government, all embedded in a strong federal structure, which is what also enters my exit index. More specifically to your point, the CDU/CSU would, in my opinion, never accept a referendum on EU membership as a price for a coalition with the AfD. In Austria, the FPÖ recently tried the same with the ÖVP, but to no avail.

I would also invite you to take a look at the full paper, which makes the entire reasoning and procedure behind the exit index much more transparent than was possible in this blog post: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/64565/RSCAS_2019_85.pdf

But I do agree that more than the nine indicators (across three dimensions) currently used could be added to the exit index in the future. This is also mentioned in the conclusions of my paper.

Dear Markus, thank you for the comments and the link to the paper, which I will look at. However let me make one clarification. When I wrote that in the circumstances described “there will probably be large popular support in Germany for the idea that they are being asked to pay for everyone else or take in everyone else’s refugees” I did not mean to imply that this idea would be correct. However if, for example, large numbers of refugees were to reach the German border again, I find it hard to see what the German government could do other than “take them in” since almost nobody wants a Trump-style wall, deportation is hard, and (I hope) it would be politically impossible to let migrants starve to death or deny them access to basic healthcare or education.

I’m sorry, just one more point … I think one possibility that cannot be excluded is that the EU collapses not with a bang but a whimper. By that I mean that several countries might try to escape part of the EU obligations by simply ignoring them. Article 7 allows rights to be withdrawn from individual members, but only with unanimity among all other members. As I think we have seen recently with Hungary and Poland, this means there is a risk EU members can club together to defy the EU on particular issues. Isn’t it possible that we could see a succession of cases where countries defy EU authority, until there is hardly any meaningful authority left? Or until the remaining rule-following members just decide they’ve had enough of playing a game where nobody else is following the rules, and quit?

I don’t know what effective sanctions the EU has when two or more members agree to obstruct or not implement EU legislation and ECJ rulings. Does anyone know?

The EU is a supranational, as explained by Todd Huizinga, amongst others. It is an organisation which has become an institution. Conspiracies and conspiracy theories aside, it is by now widely known that the lead-up to the development of this hegemon-in-the-making accelerated after WWII, but has a more or less continuous connection with pre-democracy and pre- The Treaty of Westfalen European elites clinging to old and deep-rooted ideas about how society should be run and who should be in charge. It is not only a deep-rooted leftover from times past, but inherent in the human psyche in the struggle for survival of the fittest. People organising themselves on a democratic basis predates Greek democracy. It was extant amongst the tribes along the North Sea coast but did not survive due to ongoing sociopolitical and associated developments. The birth of democracy in its modern European form and subsequent distribution across the globe as a working system of government never did extinguish the very human trait of the struggle for supremacy between vying groups of politically active and astute managers of people and peoples by means of psychological control.

The EU is controlled and run by a kind of people much in evidence since the western welfare state matured and started eating itself. They are the kind of people who will never give up trying to keep control once they got it or trying to regain control after they lost it. Look at the Brexit trip from the time the referendum was first mooted. They tried every trick in the book to stop the British people deciding, and after it was decided did everything possible to stop it being effected. At the moment the EU is re-organising its defences as the Tories had to give up sabotaging Brexit. It remains to be seen what Boris will make of it. Without continuous political pressure from Leavers and other democrats the result is likely to be some form of Brino. The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. This is a lesson which, evidently, needs to be recognised and worked through time and again. That is due to human nature, much like the innate need for some to emotionally, mentally, physically, socially, politically, etc. to control and exploit others. It was ever thus.

The EU will evolve, but how and what it will turn into depends entirely on to how the incumbents, now being gradually replaced on purpose by new entrants from afar, wish to partake of the process of sociopolitical democracy. Indeed, it depends on whether the incumbents will be motivated enough to be bothered at all. The voting patterns suggest no more than a third of the electorate which actually rolls up to vote is sufficiently exercised to want to force the relentless drive for domination by the old elites back into the age-old bog of their own making. Recently, the EU apparatchiks have changed their tune. They are sweet-talking the British they previously abused to such a large extent for wanting a Brexit referendum and for wanting Brexit after the Leavers got the majority. The EU elite and their well-organised, you have to give ‘em that, and well-paid cadre are not giving up. It is not just ideology, it’s a living, and a good one at that.