Who breaks lockdown rules, ask Patrick Sturgis, Jonathan Jackson and Jouni Kuha (LSE)? In this blog, they discuss lockdown compliance and lockdown scepticism on the basis of evidence from a new random sample survey.

Interest in the question of who breaks lockdown rules has intensified since Dominic Cummings’ controversial trips to and around Durham in early April. Concern has been expressed widely that Mr Cummings’ highly visible breaking of the rules that he, and others at the top of government, imposed on others, may erode public compliance with social distancing and the track and trace system that will be key to controlling the virus until a vaccine is found.

Opinion polling has consistently shown the British public to be highly supportive of lockdown. Indeed, despite the prominence afforded to anti-lockdown protests in the media and the high profile of some of its leading advocates, the position may actually be one of the most fringe ever seen in British society, with just 5% opposing the extension of lockdown in mid-April. Comparative polling by Ipsos-MORI also found the UK to be amongst the most pro-lockdown countries internationally, with the strong national consensus seemingly unaffected by the partisan polarisation that has characterised public opinion on lockdown in the US.

Yet, though the position in the UK may not exactly mirror the polarised nature of the COVID-19 response in the US, there are reasons to believe that resistance to lockdown may be more widespread and ideologically patterned than a simple binary support/oppose question can reveal. While people may support the lockdown policy overall, they may nevertheless be quite sceptical about its net benefits.

Additionally, there are indications that lockdown scepticism is becoming increasingly entwined with the Leave/Remain divide that dominates most aspects of British politics. Many pro-Brexit Tory MPs are increasingly critical of the high costs of lockdown on individual freedoms and the economy and have been pushing, both publicly and privately, for easing of the restrictions. Meanwhile, political scientist Ben Ansell has found that the behaviour of people living in Remain-voting areas suggests they are complying more with social distancing rules compared to people in Leave-voting areas, even when accounting for differences in social and economic composition between areas.

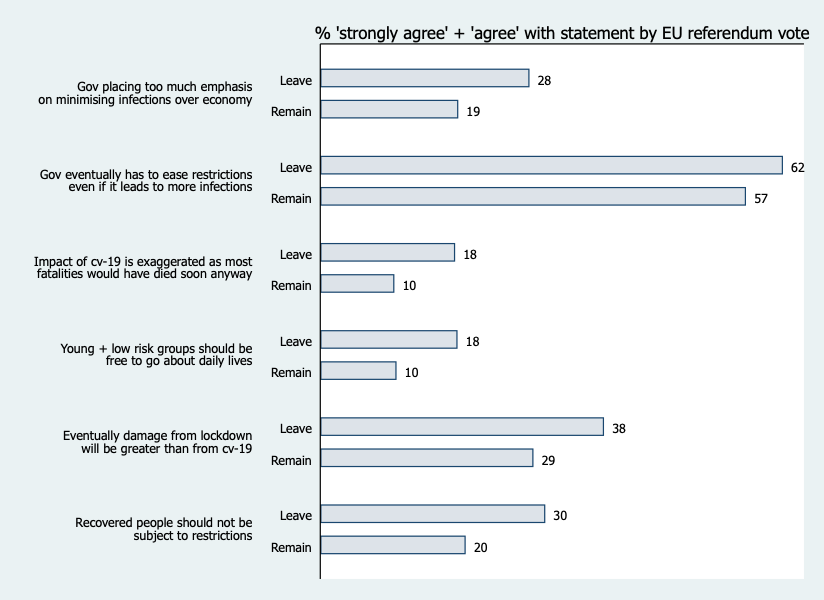

To get a better understanding of the factors underpinning lockdown scepticism and compliance, we ran a survey on the Kantar Public Voice probability panel, with 1840 interviews carried out online and on the phone[1] between 1st May and 1st June. To measure lockdown scepticism we asked respondents to state their level of agreement with six statements relating to different aspects of lockdown. These six statements, shown below, cover the balance between minimising infections vs damage to the economy, the concentration of fatalities amongst high-risk groups, and the non-COVID related impacts on health, well-being, and individual freedom:

- The government is placing too much emphasis on minimising infections from the coronavirus and not enough on keeping the economy going.

- The government will eventually have to ease restrictions on our daily lives, even if that leads to more people catching the coronavirus.

- The impact of the coronavirus is being exaggerated because most of the people dying would have died within a year or two anyway.

- Young people and other groups at low risk of serious illness from the coronavirus should be free to go about their normal daily lives.

- Eventually, the damage to people’s lives from the lockdown will be greater than the health problems and fatalities caused by the coronavirus.

- If you can prove you have recovered from the coronavirus, you should not be subject to restrictions on what you can do.

The figure below shows the percentage of the public who agree with each statement by whether people voted Leave or Remain in 2016. While only minorities agree with five of the six statements, these items reveal substantially more scepticism about the net benefits of lockdown than a binary support ‘yes/no’ question. We can also see that, on all six items, Leave voters are more sceptical about the benefits of lockdown than Remain voters, though this may, of course, be due to other demographic and attitudinal differences between these groups.  To check this, we combined the six items into a ‘lockdown scepticism’ scale, and included a range of other potentially relevant predictors of lockdown scepticism in a regression model predicting an individual’s degree of lockdown scepticism. The figure below shows the results of this analysis graphically. The ‘effect’ of each variable (listed on the vertical axis) on lockdown scepticism is shown as a blue circle, with circles further to the right of the chart indicating more lockdown scepticism. The uncertainty due to sampling variability, the ‘margin of error’, is indicated by the lines emanating right and left of the circle. If the margin of error crosses the red line that runs vertically from zero on the horizontal axis, we conclude that there is no significant effect of the variable on lockdown scepticism.

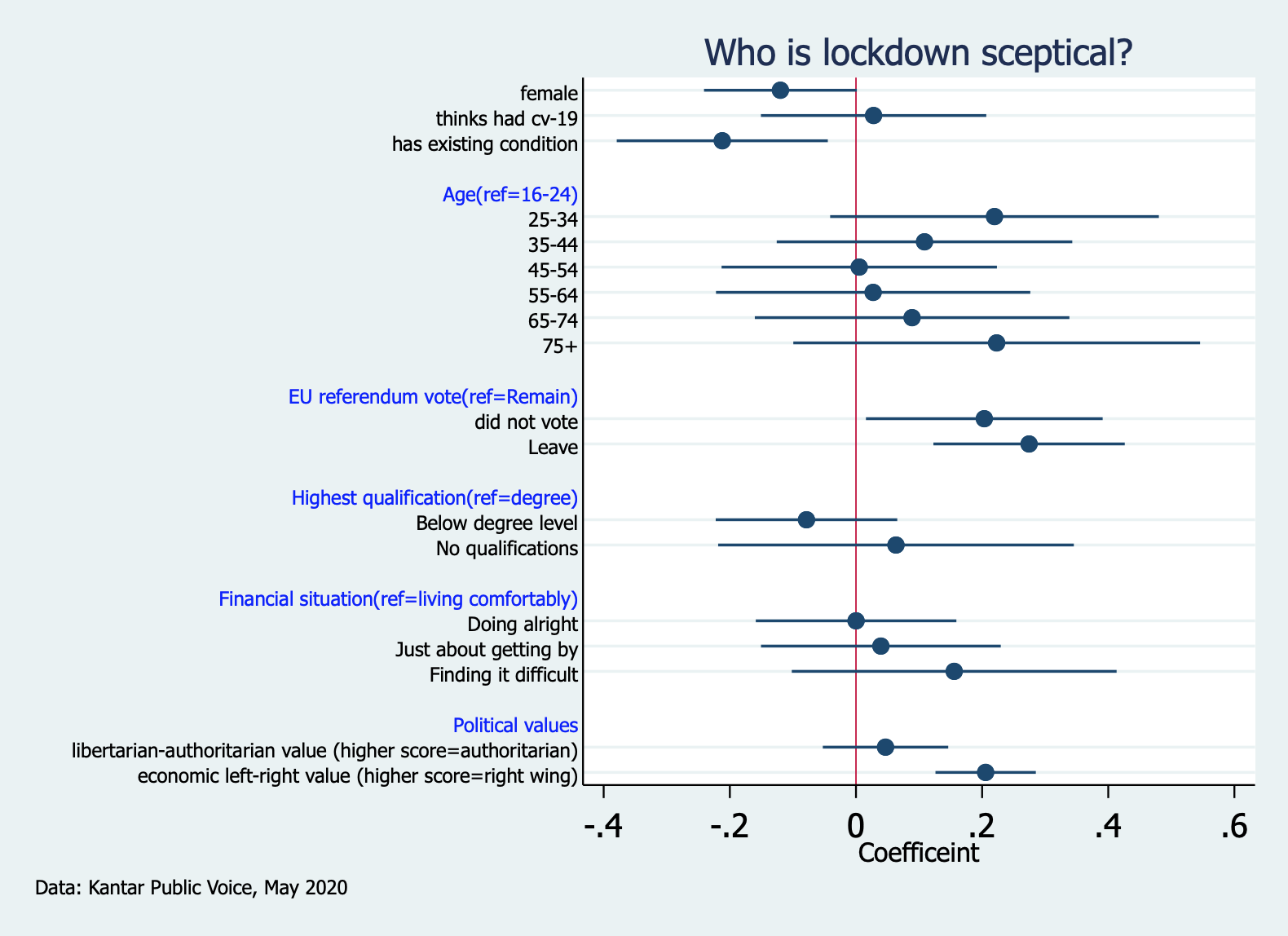

To check this, we combined the six items into a ‘lockdown scepticism’ scale, and included a range of other potentially relevant predictors of lockdown scepticism in a regression model predicting an individual’s degree of lockdown scepticism. The figure below shows the results of this analysis graphically. The ‘effect’ of each variable (listed on the vertical axis) on lockdown scepticism is shown as a blue circle, with circles further to the right of the chart indicating more lockdown scepticism. The uncertainty due to sampling variability, the ‘margin of error’, is indicated by the lines emanating right and left of the circle. If the margin of error crosses the red line that runs vertically from zero on the horizontal axis, we conclude that there is no significant effect of the variable on lockdown scepticism.

Women and people with an existing condition are less sceptical of lockdown but there is no difference in lockdown scepticism by age, education, or perceived financial situation. Likewise, people who think they have already had coronavirus are no more lockdown sceptical than those who have not.

However, the Brexit divide is still apparent, even controlling for these other characteristics, with Leavers and those who did not vote in the referendum significantly more lockdown sceptic than Remainers. In terms of core political values, there is no difference in lockdown scepticism by where people fall on the libertarian-authoritarian dimension but people who are more right-wing economically are more sceptical of lockdown. This suggests, unsurprisingly perhaps, that a key driver of lockdown scepticism is concern about the substantial damage to jobs and businesses and the unprecedented state intervention to support the economy.

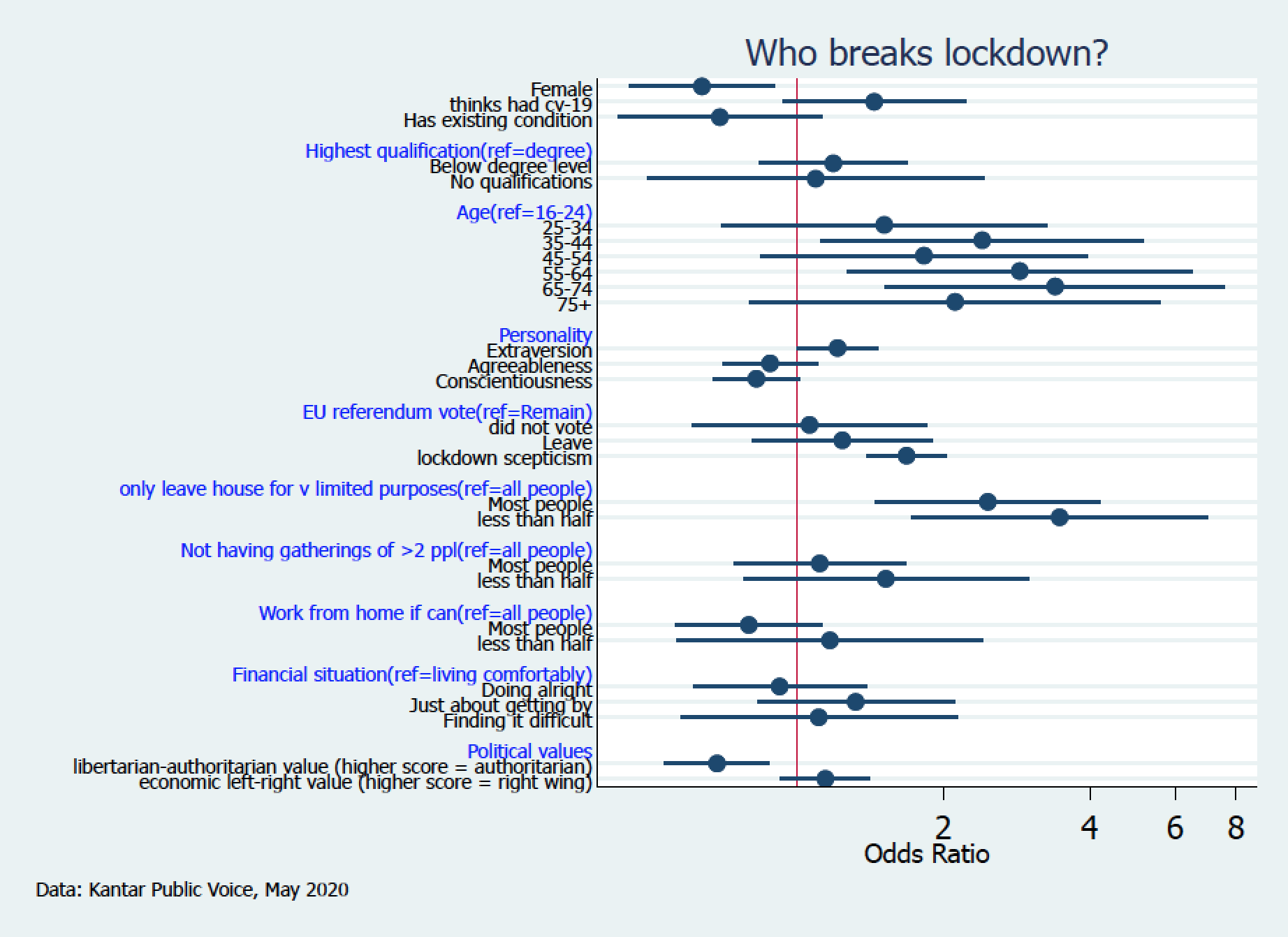

Next, we turn to a consideration of actual compliance with the rules of lockdown. We first asked respondents to tell us what proportion of the public (‘nearly all’, ‘most people’, or ‘less than half of people’) are complying with three key pillars of lockdown: only leaving the house for very limited purposes; not having gatherings of more than two people; and working from home if you can. We then asked respondents to rate the extent to which they themselves have been complying with lockdown. This showed that nearly a third (29 per cent) of the public reported not sticking to the lockdown guidelines completely, although less than 1 per cent reported sticking to the guidelines ‘not very much’, or ‘not at all’. We fitted a second regression model, this time predicting the probability that someone reported breaking lockdown guidelines, with the results presented graphically below.

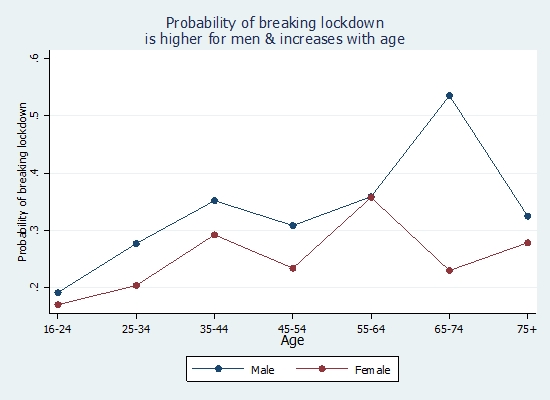

Women were less likely to report breaking lockdown, as were people in younger age categories. This somewhat counterintuitive finding about the age gradient can be seen more clearly in the figure below, which plots the probability of breaking lockdown by age and sex. Men are more likely to break lockdown in all age groups with the group least likely to comply being men aged 64-75, of whom more than half report having not stuck to the guidelines completely. While other studies have found that young men have lower levels of compliance and are most likely to be fined by the police, we find that it is older men who are the least compliant.

There is no significant difference in the probability of lockdown violation according to educational level, whether people have an existing medical condition, people’s financial situation, or by whether people think they have already had COVID-19. In terms of personality, extroverts are more likely to break lockdown, while people high on conscientiousness and agreeableness are less likely to do so, though the effects for conscientiousness and agreeableness are not statistically significant.

For political values, we find a different pattern for lockdown violation than for lockdown scepticism. There is no difference in lockdown compliance according to the economic left-right dimension but people who are higher on the authoritarian dimension are less likely to break lockdown, likely a result of the high value placed on obedience and respect for authority in the authoritarian worldview.

Social norms also seem to play an important role – people who think that others are not complying with lockdown are more likely to break lockdown themselves, although this only seems to matter if people think that others are leaving their homes for more than very limited purposes. People who think that others are not sticking to this rule are substantially more likely to report breaking lockdown themselves. This suggests that Dominic Cummings’ highly visible breaking of the ‘stay at home’ rule may well serve to reduce public compliance in the future.

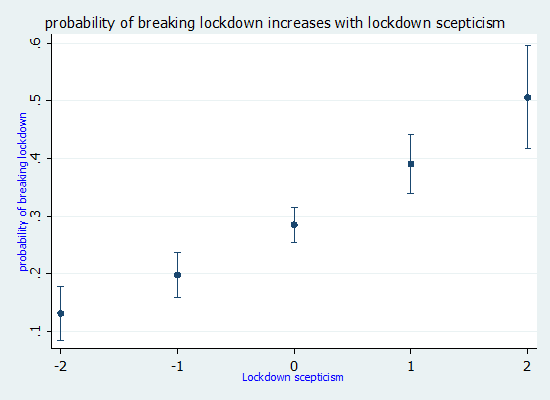

Finally, we find no difference in lockdown compliance according to people’s EU referendum vote, although there is a strong relationship between lockdown scepticism and violation of the lockdown guidelines, which can be seen in the figure below. Over 50% of people who score highest on lockdown scepticism report having broken lockdown compared to around 13% of those with the lowest levels of scepticism.

So, while we find no direct effect of EU referendum vote on breaking lockdown, there may be an indirect effect of the Brexit divide through the channel of lockdown scepticism, an idea that we intend to pursue in future research. In any event, it seems that, alongside high overall support for lockdown, there is a strong streak of scepticism at large in public opinion about its net benefits. It would not be surprising if this scepticism were to deepen as fatigue with lockdown and its wider consequences is felt ever more keenly in the weeks and months ahead.

[1] 95% of interviews were online self-completion and 5% were carried out by phone.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog or LSE. Photo © Nick Mutton (cc-by-sa/2.0).

Obviously what I’m saying here is anecdotal, not statistically proven, but I’m a remainer, a proud remainer. And I’m also against the lockdown. I voted remain because I liked the way that the EU courts ensured whitehall couldn’t carry out all the authoritarian surveillance and oppression plans it lusted for. I’ve been against the lockdown from the start, Id sooner drop dead of covid after living some length of live in a free country than live a long life under dictatorship, perhaps this is a rare position for a remainer but it isn’t a non-existent one.

P.S. very interesting you found higher lockdown violation rates for old men than young ones, seems opposite to many studies which conclude that the young are mroe likely to fit the “resisting” persoality category.

I am surprised that you don’t seem to have looked at attitudes towards government policy and control on other factors such as PPE availability; testing/tracing/quarantine; discharging covid patients to care homes; etc that have undermined the lockdown right from the start of it. In other words, the government has never provided security in the effectiveness of the lockdown because infection was not being controlled and minimised through other recommended measures already shown to be working elsewhere, and known to be required alongside a lockdown. Has there been an underlying fear/suspicion that the lockdown was a half-hearted public relations exercise to soften the herd immunity policy?

It’s amazing what experts come up with. No sooner is the public appraised of a new way of looking at society then a wavelet appears on the near horizon which swiftly grows into an academic roller washing over the beached public. The political class, right on cue, so it seems, is ready to adjust policies to suit. In the interest of public health, physical health, that is, Habeas Corpus is lost in the swirling mists of history, a fogging under which hard-won civil rights are being quietly buried, along with the essence of the constitutional arrangements of almost all countries in the West. It is almost as if there were an international movement of powerful people which deep pockets organising the undermining and dismantling of the democratic nation-state wholesale.

This trend has a long way to run. It’s early days yet. However, Brexit, and EU scepticism generally has been around and growing for decades. Likewise, what could be termed anti-globalisation sentiment is also growing in the West. As all is in flux and the West’s resident population has had a period of stability unknown before that in recent history, on top of previously undreamed of ease, leisure and peace of mind for most, it is evident the universe is calling time on this increasingly dreamy state of affairs. The old normal is being phased out. The new normal, so the experts assure us, the public(as opposed to a nebulous, as yet, group of experts, managers, selected politicians, bureaucrats and the international transnational controllers), the new normal is here. The public is under expert scrutiny and guidance, told what is what, what is going to happen, to them, the public, and what clever microchip will, in due course, be inserted if joe and jill public wishes to go about their new normal life’s business. We know, from what we have left of historical records, that power corrupts and total power corrupts totally. We know the new normal will not be normal, that it will not last, that it will not be a happy time for the sad public, those, at least, who by their nature are unable to be put to sleep. This is going to be some social experiment.

The academic experts will have a fine time analysing the public, how the public thinks, what it feels, how it needs to be guided and from time to time locked up for their own good. Nations have been around a long time, nation-states as a dominating phenomenon in the West only since the Treaty of Westfalen. Will the nation-state become totally subservient to the international busybodies now in charge? It looks as if it has in fact already happened. The people have not quite woken up yet, though. It will be some time before we can see how the public will react insofar as the public wakes up.

Who knows where and how it will end? Futurists may sketch various scenarios. Say, fifty years hence, experts all will be licensed to practice. They will be isolated from their peers and may only communicate with the rest of society by means of joe and jill public panels who will authorise what the experts will be allowed to read, write and say to each other. The same would apply to the political, bureaucratic, managerial and religio-psychological classes. Only lay philosophers selected by the public from the public may have a say in what is communicated anywhere between anyone not qualified to be counted among The Public. Just now, the public is like a herd, being farmed, milked, exploited, experimented upon and generally treated as serfs. Well, what comes around goes around and vice-versa. The Academia itself is only being used. Few academics can think for themselves. If only they who cannot think for themselves, who are controlled by the international money, could have a look at themselves. Well, would they be embarrassed and ashamed? I’m ashamed to say that they would not be, by and large. There is something missing there, in the new world order academia-Some essence, some essential insight.