At the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, individual EU countries were slow in showing solidarity with their fellow Europeans in Italy. Still, Italians want more Europe, not less, shows Catherine De Vries (Bocconi University). Italians might be critical of the direction the EU is taking, but they are in fact the more supportive of further political and economic integration in Europe compared to those from other member states. Being dissatisfied with what the EU does currently, does not mean rejecting the idea of European integration.

The coronavirus outbreak is the latest stress test for the European Union (EU), which has been hit by the UK’s departure from the club and previous disagreements over the refugee crisis and the eurozone debt crisis. In a situation that begs for solidarity and a collective response across a highly interdependent Europe, the first responses have been primarily national without much European coordination. The first response to the outbreak in Italy in late February was perhaps a case-in-point. While hospitals in Northern Italy were reaching breaking-point, other member states were slow in providing support by taking in patients or providing medical staff and equipment. While health is not a policy area in which the EU has much authority, it is the prerogative of member states, individual countries were slow in showing solidarity with their fellow Europeans in Italy.

As the pandemic spread through the continent, many member states were forced to implement lockdowns to stop the virus from spreading. The associated economic costs of putting their economies in hibernation required a European solution to support the Euro and protect the Single Market. While in late May, the European Commission launched an ambitious plan to revive the European economy (750 billion consisting of loans and grants tied to economic reforms and investment in climate and digitization), the first negotiations within the Eurogroup of European finance ministers were beset by conflict. While army trucks were collecting corona deaths in Italy, the Dutch finance Minister Hoekstra opposed financial support and demanded a review of government finances in the South of Europe. The stereotypes of Northern saints and Southern sinners, that were so prevalent in the eurozone debt crisis, quickly resurfaced.

Italian citizens, deeply wounded by the suffering caused by the pandemic and fearful of their livelihoods with a deep economic ahead, were taken aback by Europe’s lacklustre response. Commentators were quick to cite polls showing that Italians are losing faith in EU institutions and their European allies and might eventually turn their back on the EU, just like UK citizens had done in 2016. While this no doubt creates interesting headlines, I would urge caution discussing public Euroskepticism in this fashion. Public opinion cannot be simply characterized as Eurosceptic or not. It is not that black and white.

When we wish to understand the nature of public Euroscepticism in Italy, and other member states, as a matter of fact, my research suggests that it is important to keep two things in mind. First, Euroscepticism is multi-dimensional. It relates to people’s evaluations of the EU as it stands, but also to their preferences about the EU’s future. Second, Euroscepticism is not a stand-alone phenomenon. It develops in reference to people’s views about their own country. Let me elaborate both points in some more depth by focussing on public opinion data from Italy and member states that I have collected together with the eupinions team supported by the Bertelsmann Foundation.

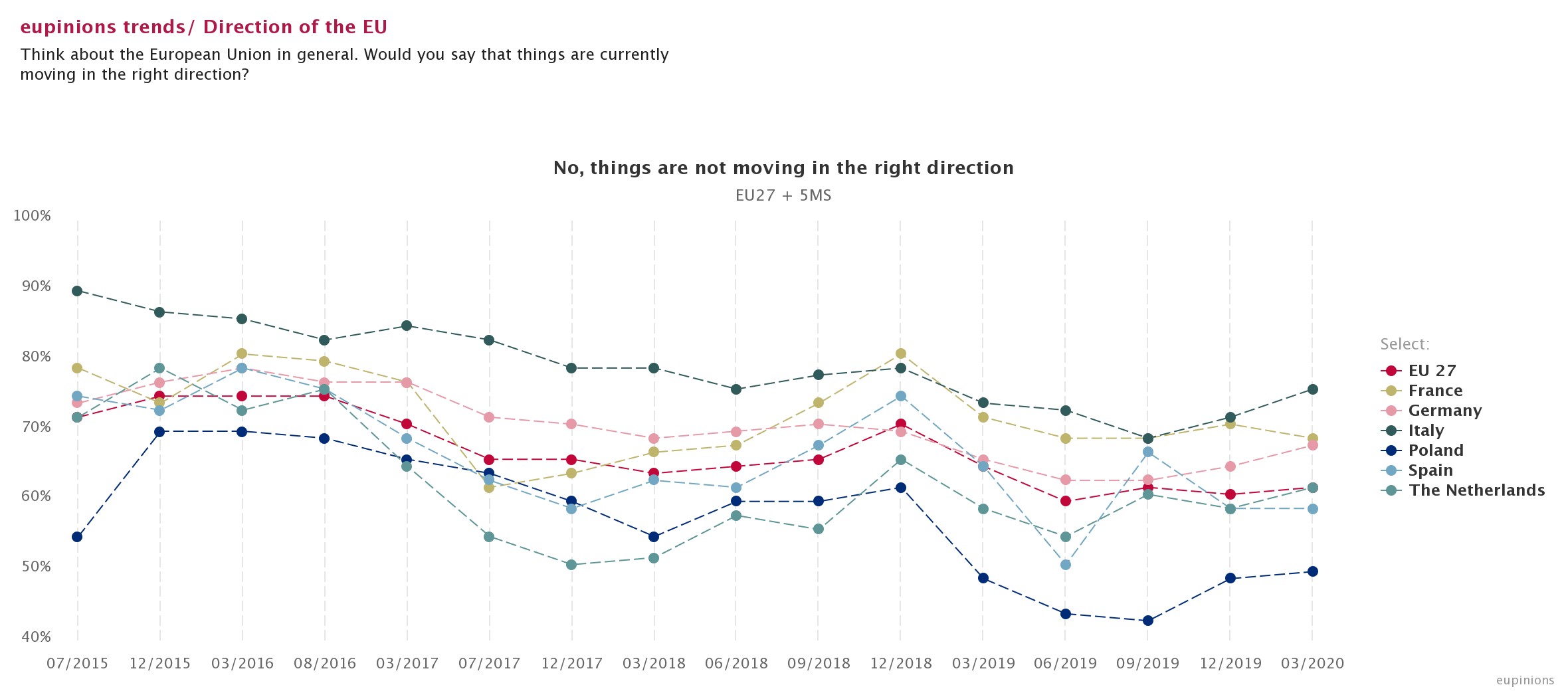

On the multi-dimensionality of Euroscepticism, when we look at the evaluations of Italian respondents of the current direction of the EU, they are indeed quite pessimistic. Figure 1 below shows the share of Italian respondents compared to those in some other member state that think that the EU is moving in the wrong direction based on the eupinions data since July 2015. The data suggest that Italian respondents are indeed negative about EU direction, in March of this year 76 per cent think EU is moving in the wrong direction. Italian respondents are also more sceptical than those from other member states. That said, by comparison, Italian respondents today are less sceptical than they were in the past. During the height of the refugee crisis in July 2015, for example, 90 per cent of Italian respondents were of the opinion that the EU was moving in the wrong direction.

Figure 1: Is the EU moving in the right direction?

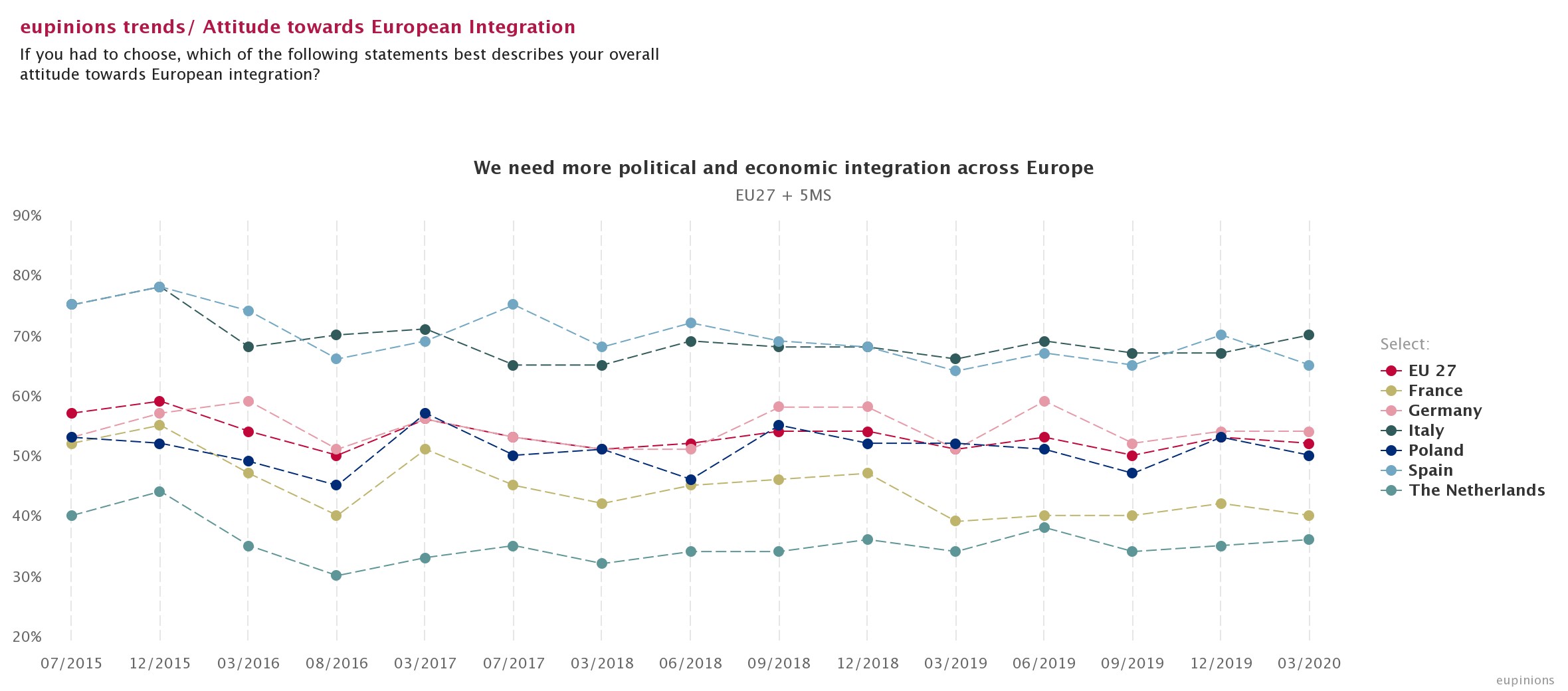

Yet, we need to remember that Euroskepticism is multi-dimensional. It is not only about evaluating the current direction of the EU, but also about what people want from the EU in the future. If we check the preferences of Italian respondents about more political and economic integration, a quite different picture emerges. Figure 2 suggests that Italian respondents are in fact the more supportive of further political and economic integration in Europe compared to those from other member states. In March this year, 71 per cent of Italians respondents state that they wish to see more political and economic integration in Europe.

Figure 2: Should there be more political and economic integration in Europe?

The data thus far suggest that Italians are ambivalent about EU: they are unsatisfied about the current direction, but wish to see more, not less, integration in the future. Against this backdrop, it will be interesting to see how Italian respondents will react to the recent Commission recovery plans.

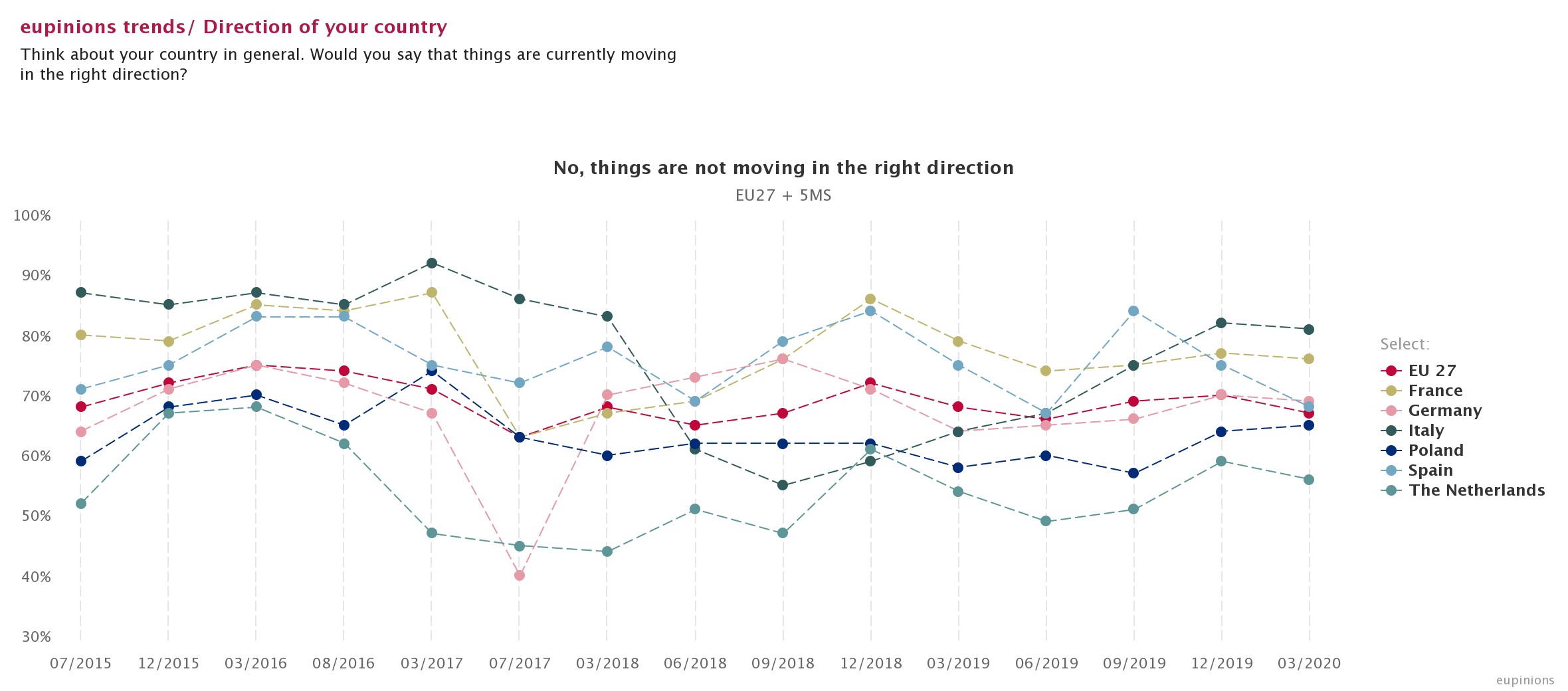

Next to multi-dimensionality, we need to think about Euroskepticism in relationship to how people view their own country. My work suggests that Euroskepticism becomes more pronounced when people are very satisfied about own country. This is because they think there would be a viable alternative to EU membership. When we look at how Italian respondents evaluate the direction of their own country, see Figure 3, it becomes clear that they are relatively less satisfied with their own country. Only 18 per cent of Italian respondents think that their country is moving in the right direction in March this year. The same is true when we look at how satisfied Italian respondents are about the state of democracy in Italy. Only 31 per cent of Italian respondents are satisfied with democracy in their own country.

Figure 3: Is the country moving in the right direction?

Relative to the national system, Italian respondents actually evaluate the EU more positively. While important individual and regional variation of course exist, it is clear that public Euroscepticism is not as straightforward as it might seem. Simply, concluding that Italian respondents are Eurosceptic misses an important point: being dissatisfied with what the EU does currently, does not mean rejecting the idea of European integration. In fact, Italians want more integration in Europe, not less.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by Elliott Brown: Some rights reserved.

You can spin it, graph it, pie chart it until the sun goes down

Its Normal.

Italy is at 175% gdp in debt.

They cannot bail out.

The Italians don’t want more Europe.Like almost everybody else, they want more money for nothing. Europe is not the EU, btw. Europe is so much more than the EU, but that aside, the Italians have made it absolutely clear they don’t want more EU conditions. They want to borrow more money at a rate of interest paid by countries such as Germany and Holland. When it comes to paying the interest, any interest, they wish to borrow more to pay the interest. As for paying off moneys borrowed, if they have to, the Italian government would like to pay off the moneys borrowed with newly borrowed moneys, borrowed at very low or negligible interest. The Italian government wishes for low interest rates so as to borrow as little as possible extra to pay the interest. On the other hand, the less interest payable, the more money available for other purposes, all else being equal.

The Italians want Europe( the EU ) to lend money to Italy, because to borrow money elsewhere in the world is more expensive without special guarantees given by, you guessed it, Europe aka the EU aka the countries whose governments are able to borrow at lower rates. The Italians want more money from Europe ( the EU ) but they want only low interest to be payable, to be paid by the Italian government with the next lot of borrowed money, from the EU, aka the countries of which most citizens have fewer private savings than the Italians, but the Italian government wants no onerous conditions attached to these borrowings from the EU, aka the northern EU member countries which are able to borrow on the international market at low rates of interest. The Italian economy is large by EU standards, with a high rate of private savings. Not counting the interest payable on borrowings, Italy is managing quite well. Unfortunately, Italian banks insist on lending money to businesses and/or people who don’t pay it back soon enough for the banks to escape the consequences. Hence, the Italian banks need evermore money put into them to keep them solvent. The Italian banking system is a big problem, because the money created by lending seems to disappear, and the moneys put into them to stabilise the banking system also goes somewhere else…., leaking like a sieve, one could say.

Italy’s Covid-19 debacle is due to China not closing its international airports until the virus was well-established in Europe, notably northern Italy which had the influx of Chinese workers in the Chinese factories in northern Italy after the ( Chinese New Year ) annual holiday break. The logical thing to do is for Italy to go to China for cheap loans. However, the Chinese do not give away their money at low interest unless other conditions are agreed by the borrower. These conditions are onerous and varied, exacting and, one surmises, not at all liked by the Italian government which wants to borrow at low interest rates and no conditions attached. The people in Germany and Holland are not happy about their governments guaranteeing cheap loans to be had by Italy at low interest and, essentially, without conditions. One-way solidarity within the EU straitjacket is becoming strained. One-way solidarity, in any context, evidently has its limits. A bit like one-way trade, or serious trade imbalances where the countries importing more than they export, thus consuming more than they produce nationally, cannot devalue their currency to balance the accounts.

Italy and the other Mediterranean EU members would like a transfer union. The peoples in the EU member states who are expected to pay for it don’t want a transfer union. Hmmm, how can we force these countries who are able to borrow at low interest to give the Mediterranean countries money annually in a transfer union? That is a problem for the EU Commission.