Will the UK uphold its commitment to Europe’s human rights regime post-Brexit? Lucy Moxham and Oliver Garner (Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law) consider the divergences between the EU and the UK on the topic of human rights and the rationale behind ECHR conditionality in the ongoing negotiations. They examine the provisions on automatic suspension and termination of law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters in the EU’s Draft Agreement of 18 March and, in particular, the meaning of the wording ‘abrogates’ in this context.

The future relationship negotiations between the EU and the UK were at an impasse ahead of the High Level stock-taking meeting on 15 June. Despite a commitment to intensified talks, disagreement persists over fisheries, level-playing field requirements, and dispute resolution. The confirmation of the UK’s decision not to request an extension to the transition period means that these issues will need to be resolved well ahead of 31 December 2020. A particular point of contention concerns law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters being made conditional on the UK’s continued adherence to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and on the UK giving continued effect to the ECHR under its domestic law, which it currently does via the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA). The Chair of the UK’s Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR), Harriet Harman MP, has recently corresponded with the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee about human rights and the future EU-UK relationship, and this post will highlight some of the concerns she raises in that context.

Background and key documents

The UK government’s White paper on the Future Relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union (July 2018) stated that the UK ‘is committed to membership of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)’. The revised EU-UK Political Declaration (17 October 2019) reflected this and set out the basis for future cooperation. In particular, it stipulated that ‘The future relationship should incorporate the United Kingdom’s continued commitment to respect the framework of the European Convention on Human Rights’. This was taken forward in the EU’s Negotiating Directives (25 February 2020), which stated that ‘the envisaged partnership should provide for automatic termination of the law enforcement cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters if the United Kingdom were to denounce the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR)’. However, the Negotiating Directives also went further than conditioning the rights and obligations in the future relationship on continuing adherence to pre-existing international commitments. They also stated that the partnership ‘should also provide for automatic suspension if the United Kingdom were to abrogate domestic law giving effect to the ECHR, thus making it impossible for individuals to invoke the rights under the ECHR before the United Kingdom’s courts’.

This position is further developed in the EU’s Draft text of the Agreement on the New Partnership with the UK (18 March 2020). Part Three relates to the Security Partnership and Title I concerns law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters. Article 3 (page 229) provides that ‘Nothing in this Title shall have the effect of modifying the obligation to respect fundamental rights and fundamental legal principles as enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights’. Article 136 (page 284) concerns suspension and disapplication. It provides, among other things, that:

- The cooperation under this Title shall be conditional upon the United Kingdom’s continued adherence to the European Convention on Human Rights and Protocols 1, 6 and 13 thereto, as well as upon the United Kingdom giving continued effect to these instruments under its domestic law.

- Therefore, in the event that the United Kingdom abrogates the domestic law giving effect to the instruments referred to in paragraph 1 or makes amendments thereto to the effect of reducing the extent to which individuals can rely on them before domestic courts of the United Kingdom, this Title shall be suspended from the date such abrogation or amendment becomes effective. Suspension shall be terminated on the date the United Kingdom domestic law giving effect to the said instruments again becomes effective.

- Notwithstanding [Article on termination of the agreement], in the event that the United Kingdom denounces any of the instruments referred to in paragraph 1, this Title shall be disapplied from the date that such denunciation becomes effective.

What is the rationale behind ECHR conditionality?

The rationale behind the provisions on ECHR conditionality is the need to provide an external guarantee to replace the principles of mutual trust and sincere cooperation which underpins membership of the EU and cooperation between EU Member States in areas sensitive to national sovereignty under the EU’s Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. For example, in the PPU judgment (25 July 2018), concerning whether Irish judges could halt a European Arrest Warrant request from Poland, the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) held: ‘the principle of mutual trust requires, particularly as regards the area of freedom, security and justice, each of those States, save in exceptional circumstances, to consider all the other Member States to be complying with EU law and particularly with the fundamental rights recognised by EU law’. Upon withdrawal from the EU, the UK will not be subject to these obligations of EU membership and it will no longer be bound by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. So, continued adherence to the ECHR, which forms part of the EU’s regime of fundamental rights protection (Article 6(3) of the Treaty on European Union), functions as a partial external substitute for this guarantee.

As the Chair of the JCHR recently stated, ‘Mutual trust in each other’s respect for human rights standards will be important in our future relationship with the EU’. She also noted, however, that ‘although the Member States of the EU are parties to the ECHR, the EU itself has not yet acceded to the Convention’ and that ‘the requirement for the UK to continue its adherence to the ECHR is unprecedented when compared to the EU’s third country agreements with other states’. In this regard, for example, the Preamble of the EU Agreement with Iceland and Norway on the surrender procedure declares that ‘this Agreement respects fundamental rights and in particular the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms’. Article 1(3) of the Agreement simply provides that ‘This Agreement shall not have the effect of modifying the obligation to respect fundamental rights and fundamental legal principles as enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights’. This echoes Article 3 of the law enforcement and judicial cooperation title in the EU’s Draft Agreement with the UK, noted above. However, in contrast to that Draft Agreement, the Agreement with Iceland and Norway does not state that cooperation is conditional on continued adherence to the ECHR and on giving continued effect to the ECHR under domestic law, and does not contain related provisions on automatic suspension and termination. This difference may reflect a breakdown in trust between the EU and the UK following Brexit, which distinguishes the current negotiations from the EU’s relations with other states in the European neighbourhood. However, the EU’s stricter approach may also be based on the fact that the UK seeks a far more comprehensive agreement on security than merely extradition, which is the sole subject of the Iceland and Norway Agreement discussed above. As EU Chief Negotiator Michel Barnier stated in his letter to the UK Chief Negotiator David Frost, ‘the EU has never previously offered such a close and broad security partnership with any third country outside the Schengen area’.

If the rationale behind ECHR conditionality is about seeking to ensure the UK adheres to external human rights guarantees, the argument could be made that the EU should also have to provide these assurances to the UK through accession to the ECHR. As noted above, the EU has yet to accede to the ECHR. Article 6(2) TEU provides for accession by the EU itself to the ECHR. However, the CJEU ruled that the draft accession agreement was not compatible with EU law (Opinion 2/13 (18 December 2014)). Accession has been stalled ever since, though negotiations are set to resume. As a negotiating tactic, the UK could refuse to accept ECHR conditionality until the EU itself accedes to the ECHR. Indeed, it has been stated that ‘The accession will also enhance the credibility of the EU in the eyes of third countries, which the EU regularly calls upon, in its bilateral relations, to respect the ECHR’. However, there is an important distinction between the EU and UK cases. The 27 EU Member States are all individual parties to the ECHR regardless of the EU’s accession; this means that the Member State police and judicial bodies with whom the UK seeks cooperation through an EU agreement are all bound by the ECHR.

What is the view of the UK government?

The UK government’s Policy paper on The Future Relationship with the EU: The UK’s Approach to Negotiations (February 2020) stated that the agreement on law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters ‘should not specify how the UK or the EU Member States should protect and enforce human rights and the rule of law within their own autonomous legal systems’. It also specified that ‘The agreement should include a clause that allows either party to suspend or terminate some or all of the agreement. This should enable either the UK or the EU to decide to suspend – in whole or in part – the agreement where it is in the interests of the UK or the EU to do so’. It stated that, ‘In line with precedents for EU third country agreements on law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, the agreement should not specify the reasons for invoking any suspension or termination mechanism’.

The Preamble to the UK’s Draft Agreement on Law Enforcement and Judicial Cooperation in Criminal Matters reaffirms ‘the respect of the United Kingdom and the Union for human rights and fundamental freedoms, for example as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights … and for the principles of democracy and the rule of law’. This echoes the Preamble of the EU Agreement with Iceland and Norway, discussed above, yet without any reference to the ECHR. The Preamble also provides that ‘it is appropriate for either Party to be able to suspend or terminate cooperation under all or any part of this Agreement, including where one Party has concerns about the other party’s level of protection of human rights, fundamental freedoms, democracy, or the rule of law’. This seems to allude to deviation from human rights protections as a discretionary rather than automatic reason for suspension or termination of cooperation.

In light of divergences between the two sides, the Chair of the JCHR recently noted that ‘The UK’s refusal to commit to continued adherence to the ECHR may seriously affect the extent of cooperation that is possible with the EU on law enforcement and judicial cooperation’. She also expressed concern that the UK’s position ‘may signal its future intention to withdraw from the ECHR, or to reform the Human Rights Act in a way that would prevent individuals from being able to bring human rights claims before domestic courts’.

Such concerns are not completely assuaged by recent evidence given to the Committee on the Future Relationship with the EU by Michael Gove MP. In evidence on 27 April 2020, he explained that ‘It is certainly the case that we are not going to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. The challenge comes from the Commission negotiating team’s request that our adherence to the ECHR be through a particular set of processes and instruments’ and that ‘It is the case that the precise means of policing our adherence to it is not one that the EU requires of any of its member states nor one that the EU requires of independent partners’. Subsequently, in evidence on 27 May 2020, when asked ‘Are your political instructions not to agree to that [‘the guillotine clause, the safeguard in Article 136’] because of the Government’s plans to water down the direct effect of the ECHR under the Human Rights Act?’, Gove denied this. Instead, he suggested that ‘It is a question of sovereignty and the EU determining whether or not our own legislation is sufficient to give effect to the rights of citizens to ensure their position under the ECHR is safeguarded’. He emphasised in this regard that ‘To say that one particular legislative mechanism is pristine, perfect and cannot be changed unless you secure the permission of another sovereign entity is an infringement of sovereignty’. However, when asked whether the government ‘want to leave open the possibility of interfering with the Human Rights Act’, Gove replied that ‘We might enhance it in all sorts of ways’.

Indeed, the current negotiations are taking place in the context of a long-standing desire on the part of the Conservative Party to repeal the HRA. A decade ago, the 2010 Conservative Party Manifesto stated ‘we will replace the Human Rights Act with a UK Bill of Rights’. The 2015 Manifesto committed to ‘scrap the Human Rights Act and curtail the role of the European Court of Human Rights’. Following the UK’s vote to leave the EU, the 2017 Manifesto stated that ‘We will not repeal or replace the Human Rights Act while the process of Brexit is underway but we will consider our human rights legal framework when the process of leaving the EU concludes. We will remain signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights for the duration of the next parliament’. Ahead of the most recent General Election, the 2019 Manifesto made a commitment to ‘update the Human Rights Act and administrative law to ensure that there is a proper balance between the rights of individuals, our vital national security and effective government’. It also proposed to set up a ‘Constitution, Democracy and Rights Commission’ to examine such issues. While the government has not published details of how it plans to ‘update’ the HRA, its past record raises concerns about the future protection of human rights.

Against this backdrop, the Overseas Operations (Service Personnel and Veterans) Bill 2019-21 is currently before Parliament. It is described as ‘A Bill to make provision about legal proceedings and consideration of derogation from the European Convention on Human Rights in connection with operations of the armed forces outside the British Islands’. The Explanatory Notes state that the Bill includes, among other things, ‘Changes to time limits for bringing claims in tort for personal injury or death, and claims for Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) violations, that occur in the context of overseas military operations’. The Secretary of State for Defence has made a statement under section 19(1)(a) HRA that, in his view, the provisions of the Bill are compatible with ECHR rights and a separate ECHR memorandum has also been published by the Ministry of Defence. However, concerns have been raised about the impact on access to justice and human rights (see e.g., the Law Society’s response).

What is meant by ‘abrogates’ in this context?

The question then is would changes to the framework for the protection of human rights in the UK, such as those outlined in the paragraphs above, meet the requirements for automatic suspension of law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, as set out in the EU’s Draft Agreement?

As noted above, Article 136(2) of that Draft Agreement provides that ‘in the event that the United Kingdom abrogates the domestic law giving effect to the instruments referred to in paragraph 1 [the ECHR and Protocols 1, 6 and 13 thereto] or makes amendments thereto to the effect of reducing the extent to which individuals can rely on them before domestic courts of the United Kingdom, this Title shall be suspended from the date such abrogation or amendment becomes effective’.

What is meant by ‘abrogates’ in this context? The Chair of the JCHR commented that ‘It is our understanding that “abrogating” the domestic law giving effect to the ECHR refers to a repeal of the Human Rights Act 1998, which incorporated the ECHR into domestic law. However, it would be helpful to clarify the precise meaning of this language, given the potential implications’. Indeed, whilst it seems that repeal of the HRA would be sufficient to trigger automatic suspension, it may not be necessary. For example, would removing the ability of individuals to invoke their rights under the HRA be regarded as ‘abrogation’ (or perhaps the subsequent clause on ‘amendments’ is intended to cover such situations)? Also, would repeal of the HRA trigger automatic suspension even if there were replacement legislation in place (for example, a ‘British Bill of Rights’)? Moreover, is ‘makes amendments thereto to the effect of reducing the extent to which individuals can rely on them before domestic courts’ the appropriate threshold here? Unless and until the text of the future relationship agreement clearly spells out the instances in which the conditions for automatic suspension would be fulfilled, and the way in which that process would operate, there will remain legal uncertainty here.

Concluding remarks – Where to next?

The UK’s continued commitment to the ECHR is clearly a priority for the EU, but it remains to be seen how the protection of human rights will feature in the future relationship agreement. It may be regarded as ironic that having decided not to retain the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights after Brexit, the UK may need to give continued effect to the ECHR under its domestic law due to a requirement stemming from its future relationship with the EU. Also, it may be speculated whether the EU would have sought to include such a condition if the UK had indeed retained the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

What provision for the protection of human rights might be acceptable to both sides? The Chair of the JCHR noted the importance of the UK continuing to adhere to the ECHR and stressed that ‘At the very least, it is important that both parties agree to apply human rights standards that are equivalent to the ECHR’ in order to ‘provide reassurance to both parties that fundamental human rights standards would continue to be respected’. In our view, the most obvious compromise would see the EU dropping the requirement for the UK to give continued effect to the ECHR under its domestic law, whilst retaining the provision for automatic termination of law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, if the UK were to denounce the ECHR. However, this would remove an impediment to the UK repealing or ‘updating’ the HRA.

The current negotiations are ongoing and are set in the context of a wider backlash against international standards and institutions. The UK’s approach to the ECHR and the European Court of Human Rights presents a risk of contagion for the wider region. The Chair of the JCHR stated, ‘It is important that the UK continues to adhere to the ECHR, not only to guarantee the ongoing protection of rights for persons in the UK, but also to set an example to other countries. We do not want to see a regression in rights for individuals in the UK or EU Member States’. As discussed above, the EU should also complete its own accession to the ECHR, five years and counting after Opinion 2/13, in order to enhance its credibility in these negotiations and to ensure a coherent and comprehensive European framework for the protection of human rights.

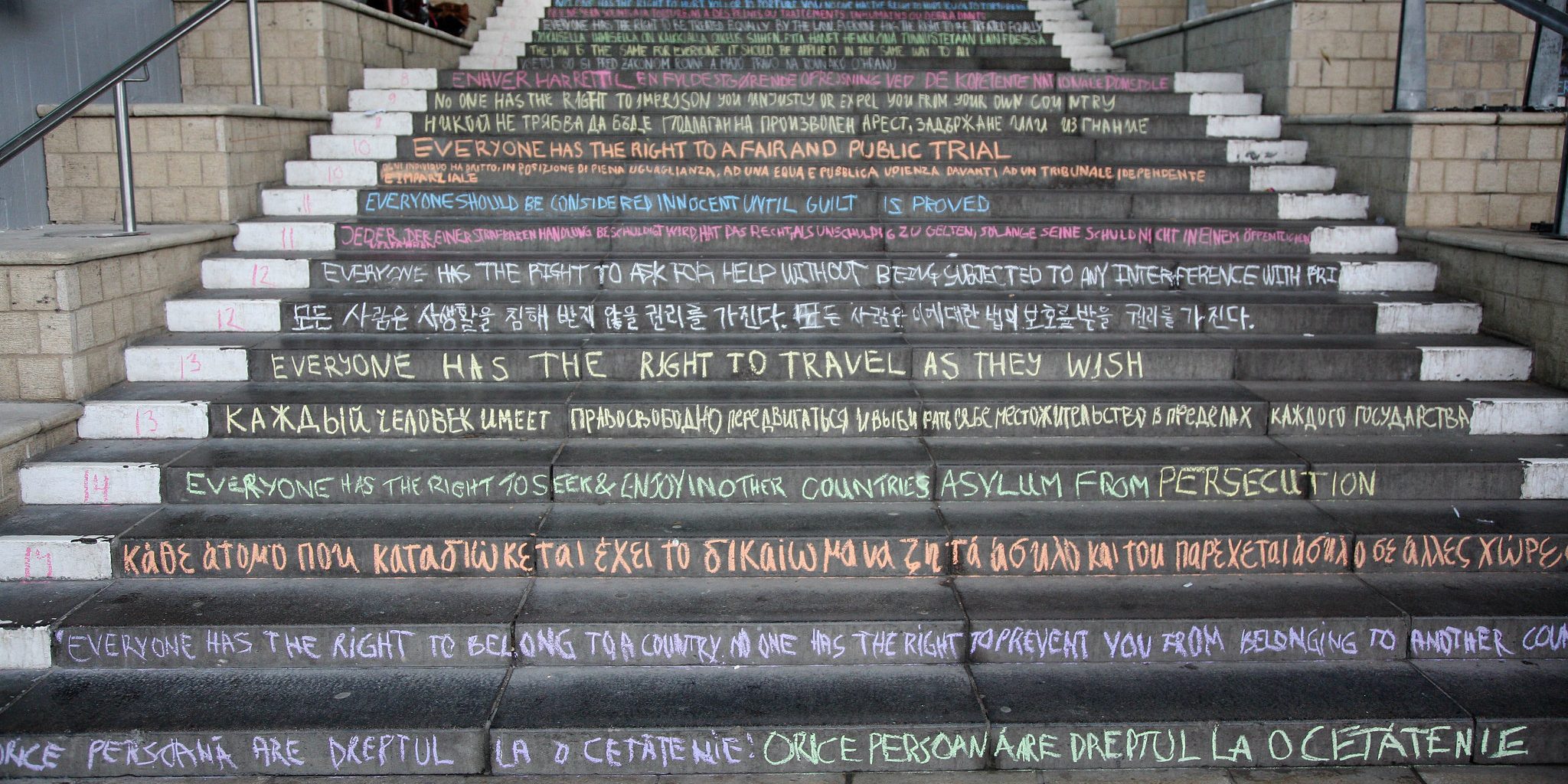

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by University of Essex, Some rights reserved.

2 Comments