With the battle over Brexit returning to the House of Commons with the Internal Market Bill, it is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture: what the British public wants in terms of a longer-term relationship with the European Union. To try to find out, Simon Hix (LSE), Clifton van der Linden (McMaster University) and Mark Pickup (Simon Fraser University) conducted a survey experiment with a random sample of British voters, where they asked them to choose between hypothetical “package deals”. This forced voters to have to make trade-offs across key issues. When faced with such choices, British voters overall prefer a “softer” form of Brexit: where the UK applies EU regulatory standards in return for quota-free and tariff-free access to the EU’s single market. However, a majority of Leave voters prefer a much “harder” trade-off: of regulatory sovereignty but restrictions on UK exports. Reconciling this difference will continue to plague British politics.

With the end of the Brexit transition period, on 31 December 2020, rapidly approaching, the likelihood that the UK and the EU fail to reach a deal is increasing by the day. While the two sides are haggling over fishing rights, state aid rules, customs checks, and other minutiae of the bargain, the preferences of the British public on the bigger trade-offs in a longer-term “package deal” – such as quota and tariff-free access for UK producers to the EU single market versus the UK having to apply EU regulatory standards – have receded into the background.

To try to understand where the British public stands on the key trade-offs at this point – after the UK formally left the EU on 31 January 2020 – we conducted a survey of 5,593 UK residents in two separate waves drawn from the Vox Pop Labs online respondent panel and fielded between 14 March and 13 May 2020. The sample was weighted against marginal distributions in population demographics, to render nationally representative estimates.

We could have simply asked people what they thought about each of the key issues separately, such as their attitudes towards market access, applying EU regulatory standards, the free movement of people, payments into the EU budget, and so on. his approach would have allowed us to gauge the strength of support for individual issues in the negotiations, but would not have enabled us to identify how people felt about the difficult trade-offs that will inevitably have to be made in a compromise “package deal”.

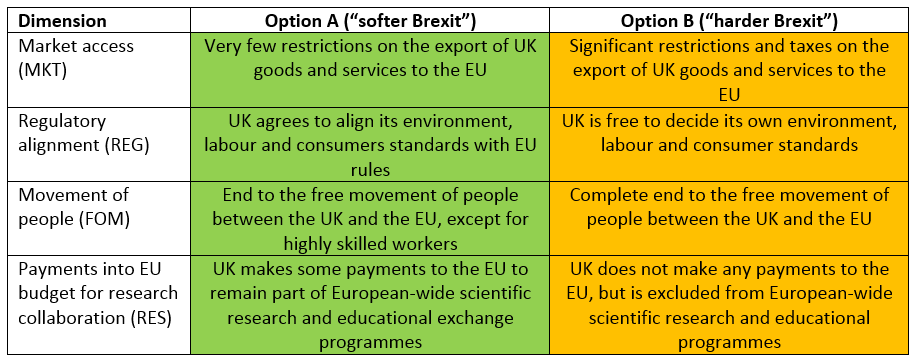

So, what we did was conduct a survey experiment using a method known as “conjoint analysis”, which is a technique originally developed in market research to understand consumers’ preferences about different aspects of a product. How this worked was as follows. First, we identified four dimensions of a Brexit deal and two possible options for each of those dimensions. To ease understanding, we tried to keep the options and the descriptions as simple as possible, as Table 1 shows.

Table 1. Softer and Harder Choices on 4 Dimensions of Brexit

Second, from these two choices across these four dimensions, we created all the possible potential “packages”: 16 in total. We then presented respondents with a series of pairs of randomly chosen packages and asked them to say which package they prefer. From this simple set up, we can identify two things: (1) how popular each package is relative to every other package; and (2) the relative popularity of the individual options.

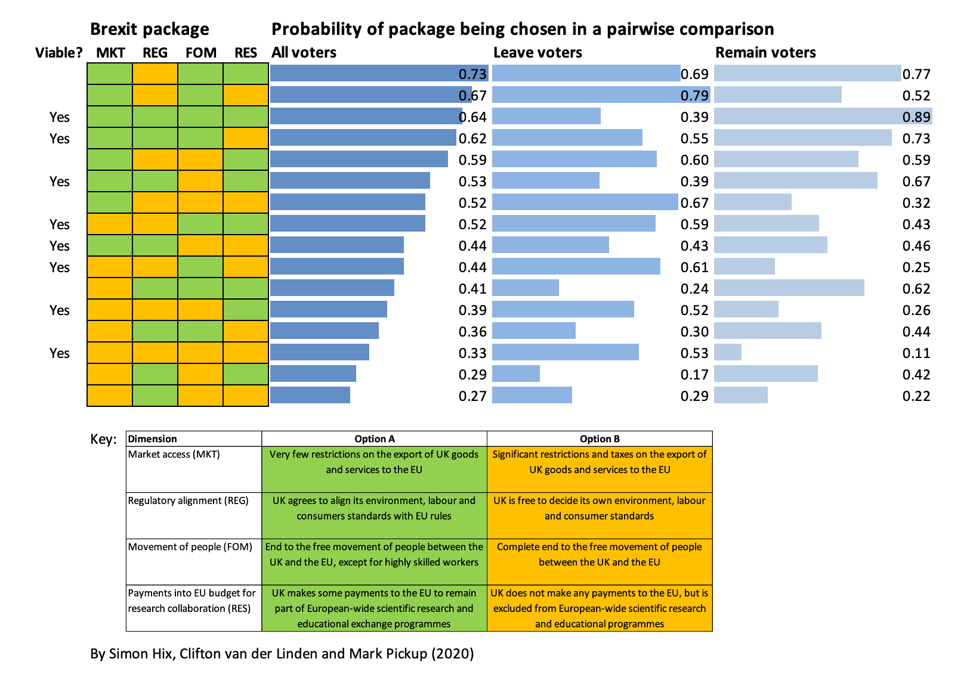

On the first of these, Figure 1 shows the overall probability that a package was preferred in a pairwise comparison, for all voters and broken down by whether someone voted Leave or Remain in the 2016 Brexit referendum. We also indicate which packages we consider to be “viable” (from the EU’s point of view), in that these packages would involve either (a) full EU market access in return for the UK applying EU regulatory standards (two green squares in the first two columns), or (b) tariffs and quotas on UK exports in return for full UK regulatory sovereignty (two orange squares in the first two columns).

Overall, the two most preferred packages for all voters (the top 2 rows in the figure) are not viable – or, put another way, they are variations of “having our cake and eating it”. Interestingly, though, the most preferred viable package amongst all voters would be a relatively “soft” form of Brexit (the third package down in the figure): with full market access (no quotas or tariffs on exports) in return for the UK applying EU regulatory standards, plus free movement of high skilled labour, and payments into the EU budget to participate in research collaboration and education exchanges.

Figure 1. Package Preferences: All Voters, and Leave vs. Remain

However, there is an important difference between Leave and Remain voters, in that while this package is popular amongst Remain voters (who preferred it 89% of the time), Leave voters prefer (61% of the time) a much harder form of Brexit amongst the viable packages: tariffs and quotas on UK exports to the EU in return for UK regulatory sovereignty, plus free movement of high skilled labour, and no payments to the EU to secure scientific collaboration (the 10th package down in the figure, the “orange-orange-green-orange” package). Meanwhile, a “no-deal” Brexit (orange across all 4 boxes) is not popular amongst either group: it was preferred only 11% of the time by Remain voters and even among Leavers, only 53% of the time. In contrast, Remain voters choose the Leave voters most-preferred viable package 25% of the time.

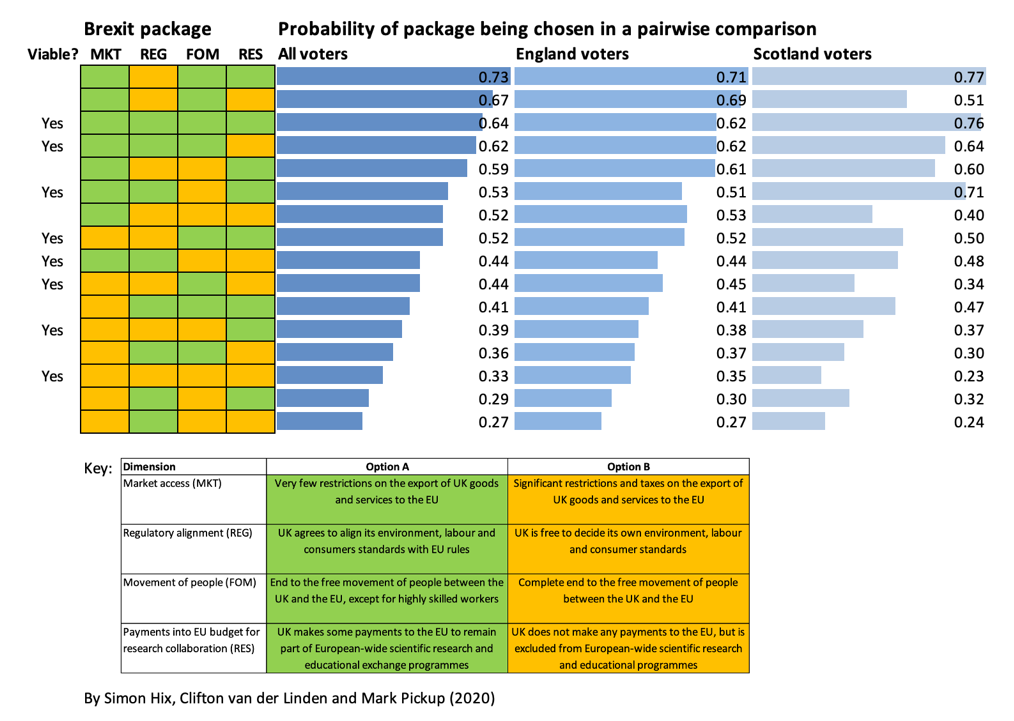

When comparing how voters in England and Scotland respond to these choices (Figure 2), some interesting differences emerge.

There is no difference between English and Scottish voters in terms of which overall package is most preferred or in terms of which of the viable packages is most preferred.

However, Scottish voters much more strongly prefer the “softest” viable package to English voters: this package wins 76% of the time amongst Scottish voters as opposed to 61% of the time amongst English voters. And, at the other end, a “no-deal” outcome (the row of 4 orange squares) is far less popular in Scotland than in England (23% compared to 35%), and in fact, is the least preferred package amongst all 16 amongst Scottish voters. This reinforces the view that a No-Deal Brexit would threaten the future of the Union, as this outcome would be highly unpopular North of the border compared to many other possible Brexit outcomes.

Figure 2. Package Preferences: All Voters, and England vs. Scotland

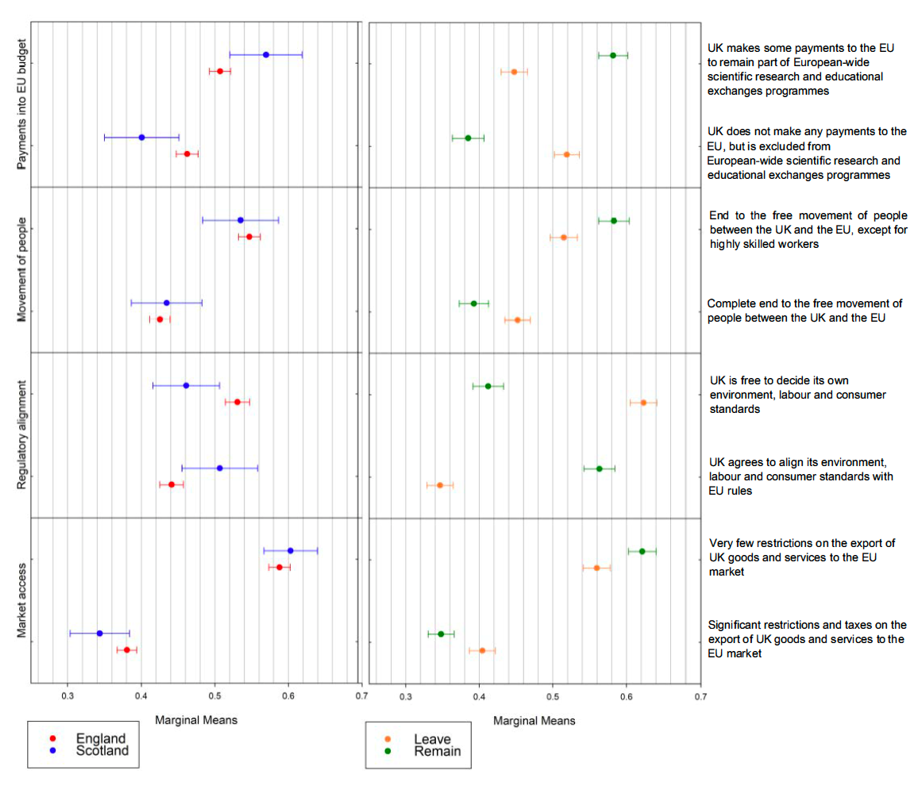

In terms of the relative preferences for the individual options, figure 3 plots the average popularity of all packages that contain a particular option. This reveals how important each individual option on each dimension was in determining whether a package was chosen over another one.

These results reveal that on two dimensions Leave and Remain voters prefer the same option. On the market access options, both Leave and Remain voters prefer packages with few restrictions over those with significant restrictions (averaging over all other options for all other dimensions), but Remain voters feel more strongly about this than Leaver voters. And, on the movement of people, both Leave and Remain voters prefer an exception for highly skilled workers over a complete end to the free movement of people, although Remain voters again feel more strongly about this than Leave voters.

Figure 3. Average Marginal Effects of an Option on a Respondent Preferring a Package

On the other two dimensions, Leave and Remain voters prefer different options. On regulatory alignment, Leave voters prefer the UK to be free to decide its own standards, while Remain voters prefer that the UK align with the EU’s standards. Leave voters feel more strongly about this than Remain voters. And on payments to the EU, Leave voters prefer the UK to not make any payments and be excluded from scientific research and educational exchange programs, while Remain voters want the UK to make some payments to continue to be involved in these programmes. Remain voters feel more strongly about this than Leave voters.

Finally, on three of the four dimensions, respondents from England and Scotland prefer the same option but on one dimension (regulatory alignment), Scottish and English respondents have different preferences. Specifically, English respondents prefer the UK to be free to decide its own regulatory standards, while Scottish respondents prefer the UK to align its standards with the EU.

Overall, our findings about what the overall majority of British voters want in terms are consistent with other research that has asked British citizens to consider trade-offs between different Brexit dimensions. For example, in September 2017, the most prominent and professionally organized citizens’ assembly on Brexit concluded that the UK should stay in the single market (and so accept EU regulatory standards) if a free trade agreement that guaranteed quota-free and tariff-free access to the single market could not be agreed.

A problem for British politicians and policy-makers, however, is that the majority of Leave voters – the core supporters of the Johnson administration – prefer a completely opposite package deal; complete regulatory sovereignty for the UK is a top objective, and are willing to pay the price of quotas and tariffs on UK exporters to the EU to achieve that.

Whatever deal the UK and the EU manage to agree to, either before 31 December 2020 or in the weeks and months following that deadline, this deal will not be the final endpoint of the Brexit process. The tension between market access and regulatory freedom will continue to be at the heart of the ongoing relations between the UK and the EU. And, the gap between the views of the majority of the British public (who place more emphasis on market access) and the majority of Leave voters (who place more emphasis on regulatory freedom) is likely to plague attempts to resolve this tension for quite some time.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics. Image: CC-BY-NC-4.0 Fotograf: Tom Nicholson

The fallacy in this article is that Leave won, twice, and don’t need to accommodate the preference of Remain voters. Remain voters and MPs certainly did not respect the views of Leave voters in the last parliament and would undoubtedly have reversed brexit completely had they won the 2019 general election.

A Soft Brexit is not Brexit as the UK would still be under EU Rules & Regulations such as the ECJ to name just one,

As soon as the Authors mentioned the other ‘minutiae’ of Fishing Rights, State Aid and Customs Checks, in their FIRST paragraph, I realised the article was not worth reading. Any agreement is predicated on the resolution of discussions on those subjects. Therefore to describe them as’ minutiae’ immediately indicates the ‘political’ leanings of the Authors and renders the article irrelevant.

This complex survey suffers from the same flaw as the decision to put the EU membership decision to a referendum without the key consequences of a leave decision being known. In Northern Ireland many months of detailed negotiations were undertaken and only when a draft agreement was arrived at were the electorate asked to approve or otherwise. The Good Friday Agreement was thus achieved with clear and informed public support. On brexit there is still a strong element of having cake and eating it.

Having said that, the fact is that the UK has left the EU and we must make the best of it.

The article is based on two flawed premises.

The first is that 5.5K people do not represent ‘the British’.

The second is that there is only one form of Brexit. It is the act of taking the UK out of the EU so that its status is that of Nigeria and Japan. There is no ‘hard or soft’ version.

And because they haven’t been specifically asked, the 17.4 million Leave voters have not expressed an opinion on the future trading relationship.

Finally, regulatory freedom will occur on December 31st 2020. the EU will no longer be dictating what is and isn’t in UK legislation.

My heart goes out to the authors. They did their fieldwork just at the start of the pandemic in the UK. Half of it was done before lockdown, the other half during lockdown. It must have been fun trying to get anyone to focus on Brexit. What’s more, I expect they wanted to publish much earlier than this, but I know academics have had a very busy and difficult summer, transferring scores of lectures into an online format.

The central conceit of the article is that organising our future relationship with the EU is like browsing through the pick ‘n’ mix counter at Woolworths (and yes, I am showing my age!). Of course, it’s not. It’s a difficult negotiation with a group of people who have their own bureaucratic priorities and ambitions, and the outcome is likely to be something that satisfies no one.

Suppose they had asked British men what they look for in a female partner? I suspect many of us would plump for a leggy, pneumatic blonde with a sweet, forgiving nature, and who’s dynamite in the bedroom and kitchen. Almost invariably, we settle for someone who is willing to settle for us. That’s life.

What is interesting is that the set of the four hard options was not the leavers’ main preference, in the way the four soft options was the remainers’ runaway main preference. In fact, looking at the eight or nine most popular preferences for the leavers, what is striking is that the only thing they would not to compromise on was regulation. The rest (including freedom of movement!) was open for negotiation. Does this suggest that leavers are more realistic than their remainer brethren?

So much useless argumentation about Brexit during the last four and a half years, first about the referendum, then about the mechanics of leaving the EU and the validity of the referendum, could have been avoided by asking one crucial question; Are they speaking and acting in good faith? Firstly about the EU leaders and leading eurocrats, then about Westminster, the government of the day and Parliament.

Once Cameron had called the referendum, the attitude on the part of the EU, through its principal spokespersons, was scathing, dismissive, nasty and generally offensive. Although the EU could conceivably be given a pass on the basis that it was protecting ‘its interests’ by making it as difficult as possible for the UK to extricate itself from EU membership and the Acquis Communautaire, which was especially instituted as a one-way wretched ratchet for the EU to ease its growing number of member countries into a Euro Federation, the attitude on the part of the EU leadership towards the UK, and towards Brexiteers especially, left no doubt as to what kind of leadership and what kind of project the EU happens to be.

To have a different opinion is not allowed in the EU project. The only input citizens of EU member states have is token, unless it happens to facilitate the federalisation of Europe under the aegis of the EU Commissariat. This is not even a Claytons democracy. The mooted democratic element in the EU is fake, a Potemkin parliament as a sop to democracy and civil rights.

The national governments of EU member states should be the guarantors of whatever vestige of democracy is still possible under the EU totalitarian federalisation project, but except for the Visegrad Four, these governments are wholly coopted due to the political party system and the body politics in the EU member states being largely bought on board. As elsewhere, the politically active class is privileged and looked after by government largesse. There is a ruling class and the rest in the EU. There is a growing contingent of citizens in EU member states which are systematically reduced in their financial and economic circumstances. Until Covid came along, which has allowed the authorities to curtail civil rights even further, austerity for the politically also-ran meant a steady reduction year on year of spending power. Now, due to the restrictions, the lower middle class not privileged through its EU and related political connections is being wiped out by the death of a thousand cuts. EU politics and policy is saying: “If you’re not with us, you’re against us”, and, “If you’re against us, we will slowly reduce you to penury by weeding you out of the economic as well as the political equation.

The EU totalitarian leadership has shown itself to patently not be acting in good faith in relation to anyone thinking to extricate themselves from the EU federalisation straitjacket. This is indeed the jail you can check out of, but never Leave unless you fight your way out. Brexiteers and anyone taking notice know this now for a fact. This means, as has been obvious all along, that unilateral action and a take-it-or-leave-it attitude in negotiations with the EU is the only position worth pursuing. However, the UK polity, the Establishment, the media and much of the professional political agitator class has been working to sabotage Brexit. Although the majority of the world’s nation-states are sovereign and functioning independently, this is deemed too difficult to attempt for the incumbent political gravy train occupants in Westminster.

Except for a number of honourable exceptions, the UK political class have not been acting in good faith. They have, in fact, been pulling the wool over the eyes of the public, taking the mickey and sticking the political finger up to those who voted Leave and others who might support democracy and civil rights, neither of which is to be had under the EU totalitarian rule.

However, the UK electorate in toto has voted this lot back in twice now, in some configuration or other. Who is nominally in charge is immaterial, for the time being. Meantime, the useless arguments persist, because people fail to take note of what is happening or, possibly, because the people arguing are themselves not speaking in good faith, but simply playing the political game at the more mundane levels. That’s politics. All is fair in love and war-politics is war, even in a democracy, and even more so in a situation where democracy has been turned into a sham, a parody, a Potemkin theatrical performance.

“organising our future relationship with the EU is like browsing through the pick ‘n’ mix counter at Woolworths”. What you refer to as a ‘conceit’ of the article is precisely what the article is designed to highlight – that the top preferences of both Remain and Leave voters are for unattainable packages. Only once these are taken off the table do we see the central dilemma – is the UK-EU future relationship to be constructed on a foundation supported by a majority of voters (but not of Leave voters) or one supported by a majority of Leave supporters but not of overall voters?

The die was cast in the months after the referendum when no steps were taken to build a consensus of voters’ ‘revealed preferences ‘. Instead, Brexit Ultras and hard line Remainers were indulged. A Greek tragedy.

It would have been difficult if the Cameron government and Parliament had been simply incompetent, but Brexit would have happened regardless. However, as has been made plain and painfully obvious since, the assurances given by so many worthies and people of note, not least the then PM himself at the time, were melted down in secret as soon as the result was known, while a gobsmacking slow motion political pantomime was enacted and maintained until this day. Boris is for Brino, that much became clear soon after the last GE, whatever justifications he himself pulls from his magic hat of the day. The political establishment, ably aided and abetted by the media, the corporate think tanks, the Academe and the entire EU wretched road show was and is still dedicated to sabotaging Brexit. The referendum questions were as clear and unambiguous as can be. Instead of going on strike and absenting themselves from running the country, they set about lying and cheating big-time. Well, in a democracy, even when it is not a democracy, the politicians and bureaucrats can do as they like, get paid heaps, look forward to a fat pension, no matter how traitorous their behaviour, no matter how they abuse their positions of power, which they have by the grace of the electorate, and their constituencies in question.

Very well crafted article. But I wants to add that brexit also have impacts on the migration for other european national. My other family members are already shifted to uk and I am also planning. But this decision also hurts economically. We were very set at spain and now looking for jobs at uk.

Great insight into an issue that continues to divide the country in an unhealthy way. If only this kind of analysis could have been done before the referendum perhaps we could have found a compromise that people could unite around. As it is I fear we’re heading for the extreme partisanship we see in the US.

he majority of Leave voters – the core supporters of the Johnson administration – prefer a completely opposite package deal; complete regulatory sovereignty for the UK is a top objective, and are willing to pay the price of quotas and tariffs on UK exporters to the EU to achieve that.

Interestingly, if you order the scenarios a little differently in your first chart to create eight pairs of scenarios, each pair with everything the same except the regulatory alignment/ regulatory independence option, you see that both Leave voters and the General population prefer regulatory independence in every single case. (And Remain voters prefer regulatory alignment in every single case). In other words there is a clear preference (from Leave voters and the General population) for regulatory autonomy regardless of whatever else is agreed.

I also disagree with your decision to effectively disregard the non-viable scenarios. If I understand correctly you presented participants two scenarios and asked which they would prefer. Of course everyone prefers to have unhindered market access if possible. If you asked me if I liked an option involving unhindered market access and regulatory autonomy I would vote for that myself – it doesn’t mean that I would think such a scenario likely to be available. And if it were a choice between regulatory autonomy and unhindered market access I would choose regulatory autonomy every single time. I think most leave voters would. Of course, to test this you would need to re-run your test without the non-viable scenarios included. Why did you include those scenarios if you planned to discount them anyway?