The global financial crisis that unfolded in 2008, and the economic recession it subsequently caused, led to a huge increase in UK unemployment and a large contraction in the general level of demand for goods and services. Our news was dominated by large numbers of lay-offs and job losses in monolithic firms that are household names to us. Against this backdrop, senior UK government ministers increasingly began to see the small business sector as a fundamental part of the solution to the country’s economic problems.

This assumption has some credibility as the evidence does suggest that smaller businesses tend to be more flexible, responsive and resilient than their larger, more bureaucratic counterparts due to the concentrated nature of decision-making in smaller entrepreneurial firms, closely-held ownership, and the lack of hierarchy. Resilience, despite a relative lack of resources, relates to entrepreneurial characteristics such as the desire for independence, to be in control of ones’ own destiny, but also to the closer inter-personal relationships between the entrepreneur and the workforce.

In short, it is harder, psychologically rather than legally, to get rid of a personal friend or family member than a faceless employee amongst thousands. Equally, small firm workers are more closely tied to the firm and are often willing to work with the entrepreneur to overcome problems when they arise. On a more tangible level, smaller businesses, for a variety of reasons, not least capital constraints, tend to adopt a more labour intensive mode of production thus any increase in demand for their output is often met with an increase in demand for new people rather than buying a new machine.

The ‘special person’ view of entrepreneurs, one which is favoured by the media for obvious reasons, but has its roots in Schumpeterian theory dating back to 1942, allows for periods of economic and social upheaval to create new opportunities for entrepreneurial action. Yet even if we generally believe that the small business sector is more dynamic and opportunistic than the large firm sector, they are certainly not immune to large contractions in the general demand for goods and services.

But within the small business sector there is evidence that periods of disequilibrium and economic instability are precisely the times when the best entrepreneurs are able to take advantage of new opportunities as large firms and the public sector withdraw from markets as was the case in the UK and worldwide. This is an entrepreneurial quality effect. This occurs as in periods of economic growth more people become willing to pursue an entrepreneurial career path, but the marginal quality of the last entrepreneur declines. In recessions, low quality, marginal, entrepreneurs exit the market. In short only the fittest survive.

Our research

Against this backdrop we wanted to examine the data and find out what really happens to smaller businesses in a time of economic crisis. We focused on 4 key questions:

- How many smaller businesses still managed to grow in the recession?

- Was the small business sector able to maintain its employment levels during the recession?

- What types of entrepreneurs and smaller businesses had the capability to grow and create jobs during the recession (is there an entrepreneurial human capital (EHC) effect)?

- Can smaller businesses provide the future growth that will create new employment opportunities as the economy emerges from recession?

Our broad purpose was to add to the general understanding of what really happens to the small business sector during a severe economic downturn. This will enable us to speculate about the potential contribution of the small business sector to future economic growth. This is of great importance given the political onus placed on the small business sector to provide new jobs and economic prosperity in the future.

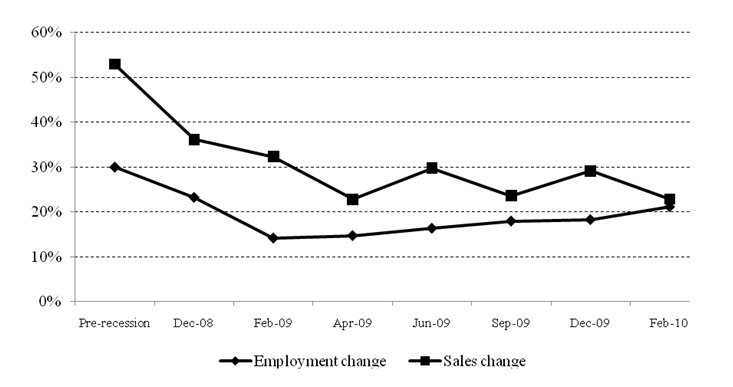

So what did we find? In terms of the question as to how many smaller firms were still capable of achieving growth during the recession, we found that between 20% and 30% of firms grew their sales – much less than the 50% that grew in more favourable economic conditions. On jobs, between 15% and 20% of firms grew their employment during the recession, but again this is lower than in the pre-recession period when 30% grew their employment. This suggests that the recession had a very strong adverse effect, at least in the first six months, on the ability of firms to grow.

Figure 1: Proportion of business with increased sales and employment before and during the recession

*Base: All SME employers (weighted data); unweighted N = 2,396 (pre-recession N = 2,138).

During the recession, it is the access to financial resources rather than the more subjective measures of human capital that are more important determinants of recessionary growth, especially sales. This suggests that in more stable economic environments many more firms are able to take advantage of general growth in demand without having to compete vigorously with other firms and entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, during a recession when the whole small business sector is further constrained by limited resource, only the entrepreneurs that have access to essential financial resources can manage to achieve growth.

Further, we also identified a positive synergy between sales and employment growth. This positive relationship is only slightly diminished in terms of its effect size during recessions. What this does suggest is that any policy levers that stimulate either job growth or sales growth will be more likely to create a positive economic multiplier.

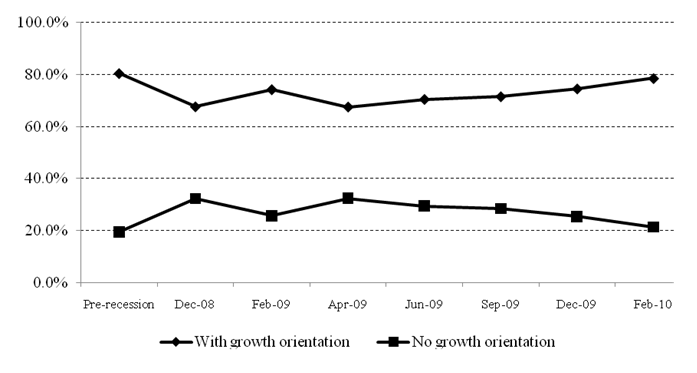

In relation to our fourth, and final, question relating to future growth orientations, we have several important insights. Firstly, general growth orientations do decline during a recession, with 10% fewer firms reporting these intentions, but this depressing effect begins to recover within six months of the onset of the recession.

Figure 2: Proportion of business with a growth orientation before and during the recession

*Base: All SME employers (weighted data); unweighted N = 2,396 (pre-recession N = 2,138).

Conclusions and Implications

Recessions do take their toll on the smaller business sector, but these effects appear relatively short lived in general and affect specific types of small businesses and entrepreneurs more than others. But perhaps our most significant finding is that in a stable and growing macroeconomic environment, growth in more randomly spread across all types of firms and entrepreneurs. This is not true in periods of economic downturns when only the best entrepreneurs, in terms of larger size and better access to finance, are able to grow their businesses.

For policymakers our results suggest that helping firms’ access finance may create a positive growth multiplier, and many countries have adopted this policy position. But more importantly, any policy levers that stimulate jobs or general spending in the economy will help create a positive jobs-growth multiplier as they tend to operate in parallel in smaller firms.

As to the general capability of the small business sector to grow and help drag depressed economies forward, our findings do offer some support for the contention that smaller businesses are more resilient and flexible enough to cope with the disequilibrium caused by economic recessions.

This post first appeared in LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog. Featured Image Credit: pkdon50 CC-BY-2.0

Marc Cowling is Professor in Entrepreneurship at the University of Brighton. He was previously Professor and Head of the Department of Management Studies at Exeter Business School.