It is indisputable that many ports and coastal communities around the UK have lost many of the boats and fishers that contributed so much to their coastal character. So where did all the fishers go? And what is the right policy response?

Any analysis of UK fisheries needs to begin with a history of overfishing because its legacy, and our continued struggle to end the problem, shapes much of fisheries management today. Massive fish hauls into the UK during the twentieth century depleted fish stocks such that fish populations could not reproduce as fast as they were being harvested. It is clear to us now that this practice would not be sustainable, but the data shows that landings had already begun declining in the first half of the century.

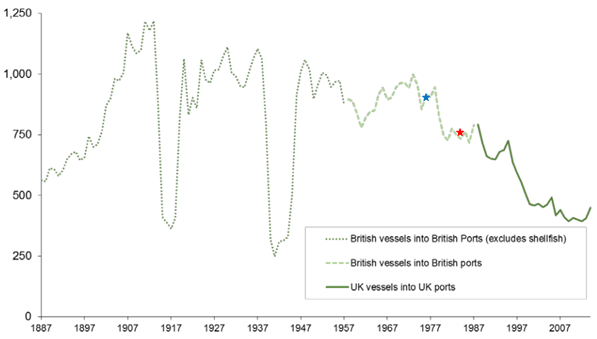

Figure 1. Landings of fish in Great Britain/UK (thousand tonnes) 1887-2014

Source: UK Parliament

The blue and red stars on the graph refer to UK ascension to the EU and the beginning of quota management under the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). Hardly the start of the trend, but hardly a reversal either.

Yet inferring stock health from landings is indirect and the effect is delayed. Behind this trend and in our waters something different is happening. Despite widespread misconception, it is now the case that most commercial fish stocks in EU waters are actually increasing in size, with North Sea cod being the most prominent example. A decade ago the stock had nearly collapsed. With the exception of two world wars, this is likely the first time period in recorded history where fish stocks are increasing in size. Much of this is thanks to capping total quota amounts under the EU, which is also a key management feature of many successful fisheries around the world.

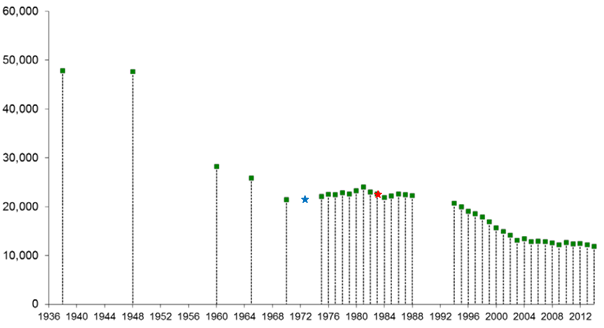

This trend in overfishing and decreased landings is clearly reflected in the number of fishers working in the UK. Another driver, at least as important, is that as is the case in many other industries, technological change has substituted capital for labour and resulted in a fishing fleet of fewer, but much larger, vessels. This technological change is why countries outside of the EU are experiencing a similar decline in fishers and small-scale ports. Norway, for example, is losing its fishers at a greater rate than the UK.

Figure 2 Number of fishers in the UK, 1938-2014

Source: UK Parliament

The recently released Brexit: The Movie spends a substantial portion of the film in the coastal community of North Shields discussing the topic of fisheries, but instead of overfishing and technological change, the focus of the segment is on the expansion of foreign trawlers in what are termed British waters.

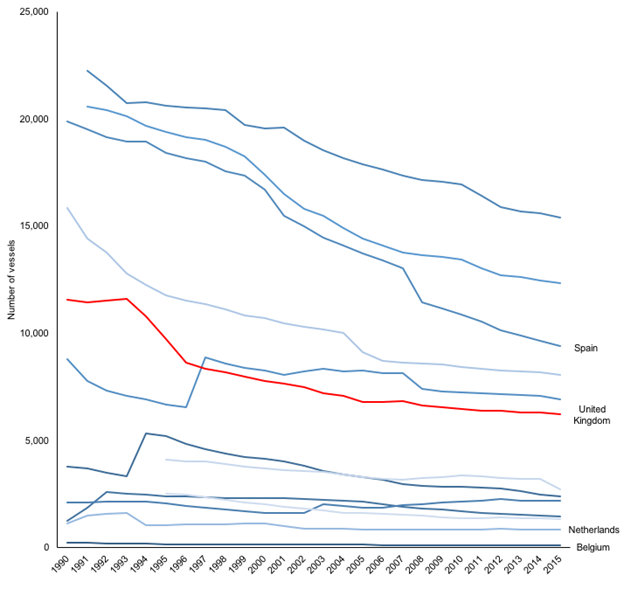

The issue of how EU fishing quotas are split between member states has been covered elsewhere, but these shares of the total quota are based on the international principle of historic fishing patterns and are fixed percentages so quotas go up or down for all member states together. Contrary to the impression from the film, there is a similar decline of vessels and jobs in other member states as seen in the UK and for the exact same reasons:

Figure 3. Number of vessels by EU member state (1990-2015)

Source: Eurostat

The irony of these claims is that the UK fishing industry is actually doing much better than the oft-accused EU member states. Profits in the UK industry continue to grow year after year and are the highest across the EU, as are profit margins. The level of investment in the industry, to buy new equipment, for example, is also growing and is the highest across the EU. Behind the headlines there’s actually a great deal of financial confidence in the industry from fishers.

None of this denies the reality in North Shields. The port is mostly made up of small vessels, which unlike the large scale sector, is not seeing profits rise. The same situation exists in Appledore/Bideford, whose suffering featured in The Guardian, while the Belgian fleet supposedly thrives. But actually the Belgian fleet is unprofitable and shrinking.

While the total amount of quota is set at the EU level (negotiated by fishing ministers), it is up to the UK government to distribute that quota to its fleet. There is currently pressure on the UK government from various groups and our own research findings, to change quota allocation rules to preserve fishing in coastal communities like North Shields and address inequality in the fishing sector.

This issue of national rules is also relevant to the complaint of foreign vessels in our waters as some of these vessels that are actually registered and flagged in the UK and have purchased quotas from (willing) UK fishers. This practice would not change under Brexit and is the equivalent of blaming the EU for foreign ownership in the Premier league. Instead, if this foreign ownership is seen as an issue then it would be for the UK government to make laws about landing a certain percentage of catch in the UK, for example.

In a joint letter to The Times, a dozen fisheries experts and previous fisheries ministers called on George Eustice, the current fisheries minister, to stop pointing his finger at Europe and act now to change UK’s quota allocation rules. If sustainable fishing jobs are to return to North Shields, this is the type of action that is required.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post appeared originally on LSE Politics and Policy.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Public Domain.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Griffin Carpenter is an Economic Modeller with the Natural Economics programme team at the New Economics Foundation. He contributes to the ‘Landing the Blame’ series of reports, which most recently include examinations of overfishing in the Northeast Atlantic 2016, the Baltic Sea 2016, and northern European Waters 2015. A full list of his publications can be found here.

Griffin Carpenter is an Economic Modeller with the Natural Economics programme team at the New Economics Foundation. He contributes to the ‘Landing the Blame’ series of reports, which most recently include examinations of overfishing in the Northeast Atlantic 2016, the Baltic Sea 2016, and northern European Waters 2015. A full list of his publications can be found here.

Spot on

The only difference now is that all the fish are being dumped dead back to the sea because of EU dictatorship. So graphs and science if you believe that is what it is, is utterly useless and does not reflect the correct biomas. Because of the EU rules honest men have had to do the very thing they find the hardest, it is high time this crazy practice is stopped and NOT by a discard ban. We’re not going to take it anymore!!!

Hi Gary,

A couple questions to consider:

-Do you think there should be limits on how much fish can be harvested each year?

-Would it really be an effective management strategy if fishers were allowed to fish above the limit?

-What should happen to the fish that is caught above the limit?

It’s pretty clear that the integrity of catch limits depend on not allowing sales about the agreed level, whether that means discarding at sea or discarding at port. This is not some innovative EU rule but can be seen in Norway, New Zealand, and other developed systems of catch limits.

As for the trends, stock biomass is recorded through scientific surveys and sampling (not just landings) so I don’t share your scepticism of the stock recovery taking place.

So you don’t seem to have an issue with dead fish being dumped back in the sea as the quotas have been met. Meaning that they may as well have just filled the landfills with the fish that are wasted. Pollute the sea against pollute the land, you decide.

Tesco fish fingers Alaska pollock. Why not British white fish???

Its clear that the fleets have all shrunk but iit would also have been interesting if you had showed the relative shares for EU member states in UK waters area 7 north sea Irish sea, west of Scotland.

Its the wasteful policies from the EU we take issue with in the UK and the small relative shares we have to fish our own grounds. In my area we have 20% of the EU tac for whitefish the French have 60% although most of the waters are UK waters and most of the fish is caught in these waters.

We have Fully documented our fishery for 4 years recorded everything we do and I can tell you I have one species that we have to discard, it is all mature fish and we have a very healthy slice of the UK TAC we have also reduced mortality for this discard by 70%. However we still have to dump tons every week over the side.

EU policy is directly responsible for this if you need any further information and evidence feel free to ask and I can back all of this up. I have also been to the commission to present my work and advise what to do, they still stuck to the policy.

It seems to me that the project (EU) is more important than the outcomes of poor policy.

I have a question for you how are you funded and will you be brave enough to print my story of hard evidence and facts of someone who has an open mind on the EU but has seen first hand how it effects fisherman on a daily basis.

I look forward to your reply. David Stevens MFV Crystal Sea

Hi David,

Yes, the relative share of quotas between member states and the decline of local ports are the two arguments about fisheries and Brexit that I see most often. I research the economics of the industry so I wrote about the latter for this blog, but there is some good content out there on the former. In this blog I note:

“The issue of how EU fishing quotas are split between member states has been covered elsewhere, but these shares of the total quota are based on the international principle of historic fishing patterns and are fixed percentages so quotas go up or down for all member states together.”

No one paid me to write this blog but you can see my organisation’s funding on our website under “Who funds us”. While I don’t control what the LSE Business Review publishes (sorry!) I’d encourage you to submit your story for potential publication, or you could even submit a rebuttal to what I’ve written here.

The data you select does not illustrate the full picture. If you only display British landings, you ignore total catch, much of which is landed elsewhere.

It is particularly important to show this both before and after 1973 in order to stand up your claim that the fishery had already been overfished. Without total catch it is impossible to know. The reason, of course, that it is important to show this is simply that the main complaint UK fishermen have is not actually about overall consolidation policies within the industry (though there may be much to say about that) but is instead about the distribution of what was perceived to be a British resource. You can say that this is done in relation to historic claims if you wish, but you need to demonstrate that I’m afraid. What proportion of fish caught in British waters was caught and landed by British fishermen in British ports both before and after 1973? And what proportion of fish caught in British waters was caught and landed by non-British fishermen in non-British ports. That’s the question.

Until you answer these questions, the article and the argument may fairly be considered misleading.

Hi Douglas,

The link between trends in landings and stocks is, as I mentioned, indirect. We’re also constrained by what data is actually published.

Your alternative explanation that the landings decline is due to a change in port nationality is interesting, but it doesn’t match with what we know about stock health. See, for example, the citation in the blog here:

“Massive fish hauls into the UK during the twentieth century depleted fish stocks such that fish populations could not reproduce as fast as they were being harvested.”

Dear Griffin,

But you could make estimates based on actual quotas. My assumption would not be to deny historic overfishing, but just to see the extent to which what is claimed as a ‘British renewable resource’ was simply divided up after EU entry.

And just looking at the data in your own article and imagining a regression, despite an obvious period of relatively high catch just before WWI, if you were to plot a regression from 1887 to 1973 you would find the catch going up, not down. It is only after 1973 that the British catch falls significantly. From about 1920 to 1973 it looks pretty stable to me.

According to a chart on Page 6 of the UK Fisheries report from which you extract your data the total catch landed in UK and overseas in 1994 is not much different to 1974 UK catch (when it was presumably all caught and landed in the UK), but the UK share is by then quite a bit lower, before falling much further to about half the fish caught in UK waters. But even then, the total catch (despite bit of a dip between 2006 and 2010) is now around the historic mean dating back to the 1920s.

So, observationally at least, the fishermen have a point, and the EU may have merely swiped half of the UK’s fish under the false pretext of overfishing.

Here is a link to that report, just in case you didn’t use it.

researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN02788/SN02788.pdf

Good piece.

Ironic that the UK industrial fleet, whose profit levels are amazing… Really amazing …, continue to work against the discards ban.

Aaron

Please can you tell me why U.K. fishermen would sell their licences to the Spanish?