Fishing is a proud industry and its struggle has been propelled to prominence in the debate on the EU referendum next month. Griffin Carpenter argues that, despite what Brexit: The Movie claims, the genuine grievances of the fishing industry should be directed at the UK government, not the EU.

Fishing is a proud industry and its struggle has been propelled to prominence in the debate on the EU referendum next month. Griffin Carpenter argues that, despite what Brexit: The Movie claims, the genuine grievances of the fishing industry should be directed at the UK government, not the EU.

It is indisputable that many ports and coastal communities around the UK have lost many of the boats and fishers that contributed so much to their coastal character. So where did all the fishers go? And what is the right policy response?

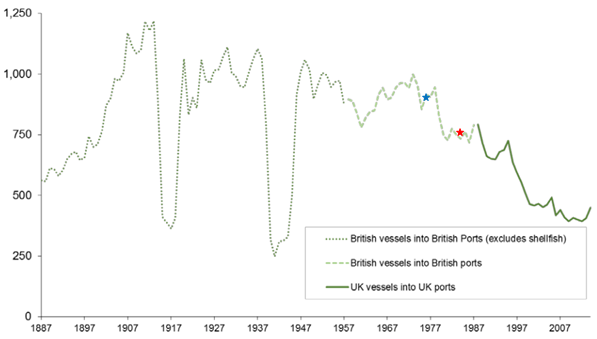

Any analysis of UK fisheries needs to begin with a history of overfishing because its legacy, and our continued struggle to end the problem, shapes much of fisheries management today. Massive fish hauls into the UK during the twentieth century depleted fish stocks such that fish populations could not reproduce as fast as they were being harvested. It is clear to us now that this practice would not be sustainable, but the data shows that landings had already begun declining in the first half of the century.

Landings of fish in Great Britain/UK (thousand tonnes) 1887-2014

Source: http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN02788#fullreport

The blue and red stars on the graph refer to UK ascension to the EU and the beginning of quota management under the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). Hardly the start of the trend, but hardly a reversal either.

Yet inferring stock health from landings is indirect and the effect is delayed. Behind this trend and in our waters something different is happening. Despite widespread misconception, it is now the case that most commercial fish stocks in EU waters are actually increasing in size, with North Sea cod being the most prominent example. A decade ago the stock had nearly collapsed. With the exception of two world wars, this is likely the first time period in recorded history where fish stocks are increasing in size. Much of this is thanks to capping total quota amounts under the EU, which is also a key management feature of many successful fisheries around the world.

This trend in overfishing and decreased landings is clearly reflected in the number of fishers working in the UK. Another driver, at least as important, is that as is the case in many other industries, technological change has substituted capital for labour and resulted in a fishing fleet of fewer, but much larger, vessels. This technological change is why countries outside of the EU are experiencing a similar decline in fishers and small-scale ports. Norway, for example, is losing its fishers at a greater rate than the UK.

Number of fishers in the UK, 1938-2014

Source: http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN02788#fullreport

The recently released Brexit: The Movie spends a substantial portion of the film in the coastal community of North Shields discussing the topic of fisheries, but instead of overfishing and technological change, the focus of the segment is on the expansion of foreign trawlers in what are termed British waters.

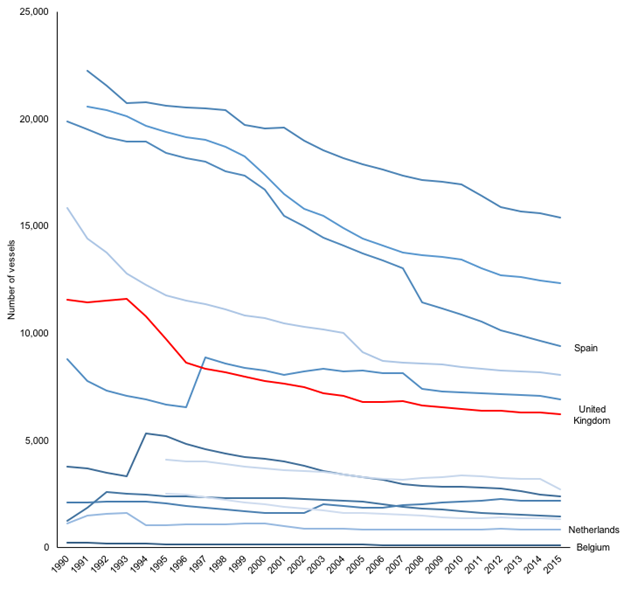

The issue of how EU fishing quotas are split between member states has been covered elsewhere, but these shares of the total quota are based on the international principle of historic fishing patterns and are fixed percentages so quotas go up or down for all member states together. Contrary to the impression from the film, there is a similar decline of vessels and jobs in other member states as seen in the UK and for the exact same reasons:

Number of vessels by EU member state (1990-2015)

Source: Eurostat

The irony of these claims is that the UK fishing industry is actually doing much better than the oft-accused EU member states. Profits in the UK industry continue to grow year after year and are the highest across the EU, as are profit margins. The level of investment in the industry, to buy new equipment, for example, is also growing and is the highest across the EU. Behind the headlines there’s actually a great deal of financial confidence in the industry from fishers.

None of this denies the reality in North Shields. The port is mostly made up of small vessels, which unlike the large scale sector, is not seeing profits rise. The same situation exists in Appledore/Bideford, whose suffering featured in The Guardian, while the Belgian fleet supposedly thrives. But actually the Belgian fleet is unprofitable and shrinking.

While the total amount of quota is set at the EU level (negotiated by fishing ministers), it is up to the UK government to distribute that quota to its fleet. There is currently pressure on the UK government from various groups and our own research findings, to change quota allocation rules to preserve fishing in coastal communities like North Shields and address inequality in the fishing sector.

This issue of national rules is also relevant to the complaint of foreign vessels in our waters as some of these vessels that are actually registered and flagged in the UK and have purchased quotas from (willing) UK fishers. This practice would not change under Brexit and is the equivalent of blaming the EU for foreign ownership in the Premier league. Instead, if this foreign ownership is seen as an issue then it would be for the UK government to make laws about landing a certain percentage of catch in the UK, for example.

In a joint letter to The Times, a dozen fisheries experts and previous fisheries ministers called on George Eustice, the current fisheries minister, to stop pointing his finger at Europe and act now to change UK’s quota allocation rules. If sustainable fishing jobs are to return to North Shields, this is the type of action that is required.

About the Author

Griffin Carpenter is an Economic Modeller with the Natural Economics programme team at the New Economics Foundation. He contributes to the ‘Landing the Blame’ series of reports, which most recently include examinations of overfishing in the Northeast Atlantic 2016, the Baltic Sea 2016, and northern European Waters 2015. A full list of his publications can be found here.

Griffin Carpenter is an Economic Modeller with the Natural Economics programme team at the New Economics Foundation. He contributes to the ‘Landing the Blame’ series of reports, which most recently include examinations of overfishing in the Northeast Atlantic 2016, the Baltic Sea 2016, and northern European Waters 2015. A full list of his publications can be found here.

I think your missing a couple of very important points by just using the graphs you provided . Mainly the landings by British vessels into British ports one. Most of this fish will have been caught in Icelandic,Faroese and Greenlandic waters by the distant water fleet that Britain used to have and not in British territorial waters.

The second one about British fishing jobs does this account for the foreign crews crewing boats ? Or does it account for boats that are tied up and unable to work ?

Hi Stuart,

You raise a good point about the effect of the cod war on overall landings. That said, even with that explanation it’s not clear why the EU is to blame for the Icelandic conflict. That said, we also know from the stock trends that this period was seeing decline. See, for example, the citation in the blog here:

“Massive fish hauls into the UK during the twentieth century depleted fish stocks such that fish populations could not reproduce as fast as they were being harvested.”

The graph on the number of fishers includes both full time and part time fishers but page 10 of the linked source shows that there is no real difference whether you use full time, part time, or both. These are fishers working in the industry and earning revenue. The data includes foreign crew (Filipino, Dutch, etc.) as is standard reporting.

Hi Griffin. Interesting article which raises some useful points and which I think are worth discussing further. As I was reading there a couple of questions came to mind which I’d be interested to hear your perspective on.

1. The landing graph shows significant declines over the last 50 or so years. Do you have any information on how much of that decline is due to depleted stocks and how much is due to policy?

2. The decline in vessels refers to number of vessels but doesn’t seem to provide any information about increasing size of vessels nor about enhanced fishing methods which raise catch rates per vessel. Do you have any thoughts/ insights into these factors?

Thanks again.

Hi David,

Many thanks for your thoughtful questions.

Your first question is a bit tricky to answer because policy and stock depletion are not independent. If there is overfishing and the stock declines, and as a results quotas are lowered, would you say the resulting decrease in landings is due to policy or depleted stocks?

Roughly speaking, I would say that up until the early 1990s there was very little effective policy so the decline is nearly all due to stock depletion. Over the past 20-25 years we have much more effective management, but as I say, you can’t really separate the two drivers you’ve listed.

Your second question is a very good one. I wondered about this myself while writing this blog and fortunately the same Eurostat dataset has information on fishing capacity in terms of gigatonnes and kilowatts. Both of these measures have also been declining over time. What really surprised me is that both measures are decreasing at approximately the same rate as the number of vessels. I posted this graph on my twitter feed (@gwcarpenter) as I can’t find anyone else showing the trend.

Thanks again for your interest,

Griffin