The UK has voted to leave the European Union. Sara Hobolt writes that although the result has come as a shock to Britain and the rest of Europe, the signs were there that the Leave campaign could win and the discontent among British voters is mirrored in many other countries across Europe. Voters took the opportunity to ‘stick it to the elite’ and punish mainstream politicians for their reluctance to address concerns about migration.

The UK has voted to leave the European Union. Sara Hobolt writes that although the result has come as a shock to Britain and the rest of Europe, the signs were there that the Leave campaign could win and the discontent among British voters is mirrored in many other countries across Europe. Voters took the opportunity to ‘stick it to the elite’ and punish mainstream politicians for their reluctance to address concerns about migration.

There is a sense of shock both in Britain and across Europe in response to the Brexit vote. But it should not come as a shock. The polls had consistently suggested that this would be a very close race and many had put the Leave side ahead in the days and weeks leading up the vote. We also know that referendums are highly unpredictable, and that voters often vote against proposals put to them by the government and supported by mainstream political parties and experts.

The Brexit vote also represents a victory for the populist forces that have gained ground in electoral contest across Europe and the United States in recent years, generally fuelled by worries about immigration, a lack of economic opportunities and anger with the political class.

Why did British voters reject the EU?

One reason why referendum outcomes are particularly unpredictable is that they present ordinary citizens with an opportunity to “stick it” to the political establishment. A division found in many referendums, including this one, is thus one between “the ordinary people” and “the elite”. This populist argument was successfully exploited by the Leave camp who portrayed the referendum as a chance for ordinary citizens to “take back control” from the elites in Brussels.

This has strong appeal especially to voters, particularly those who feel disaffected with the political establishment and threatened by the forces of globalisation and European integration. A particular source of this disaffection was growing concerns about immigration, which have long been one of the most salient issue for British voters, but which the mainstream political parties have failed adequately to address.

The Leave side presented the referendum as a unique opportunity to vote leave to regain control of British borders and restrict immigration. Survey evidence suggests that this was a core concern among Leave voters, and ultimately outweighed the fear of economic insecurity that the Remain camp had argued would follow from a Leave vote.

Who voted to leave?

Such fears of immigration are more pronounced among voters in a more vulnerable position in the labour market. The survey data shows that it was the so-called “losers” of globalisation, those with lower levels of education and working class occupation, who voted decisively for Leave, whereas the “winners” of globalisation – e.g. highly educated professionals – were overwhelmingly in favour of Remain.

This is not a uniquely British phenomenon. We see the same divisions when we study Euroscepticism across Europe, and in many countries such concerns about the EU and immigration have been translated into a boost in the electoral support for rightwing populist parties, such as the Front National in France, Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party in the Netherlands and the Danish People’s Party in Denmark. Indeed, these are the very parties that are now calling for referendums on their countries’ membership of the EU after the Brexit vote. There was also a stark generational divide in the UK referendum. Polling evidence suggests that the over-45s voted to leave while the under-45s voted to stay in the EU.

A divided country

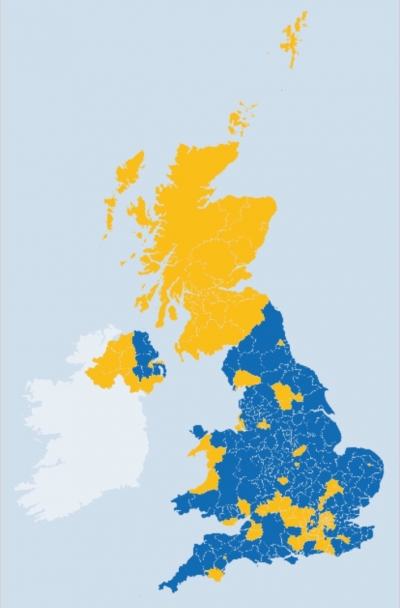

The results of this referendum portrays a deeply divided country, not only along class, education and generational lines, but also in terms of geography. While both England and Wales voted 53 per cent Leave, Northern Ireland and Scotland voted Remain (at 56 and 62 percent respectively). The only region within England to vote Remain was London, and it did so decisively with 60 per cent of the vote.

Map of the results of the referendum by area

Note: Yellow indicates that Remain won in the area while blue indicates Leave won.

Generally, the Remain side did better in the larger multicultural cities and where there were more graduates, whereas the Leave side was strongest in the English countryside and did better than expected in the post-industrial Northeastern towns with larger working class populations. Again, these divisions reflect wider inequalities and differences in British society that are likely to persist in a Britain outside the EU.

____

This post was originally posted on LSE EUROPP blog

Sara Hobolt is Sutherland Chair in European Institutions at the LSE’s European Institute. She holds an honorary professorship in political science at the University of Southern Denmark and she is associate member of Nuffield College, Oxford.

Sara Hobolt is Sutherland Chair in European Institutions at the LSE’s European Institute. She holds an honorary professorship in political science at the University of Southern Denmark and she is associate member of Nuffield College, Oxford.

i Hi Sara,

I repost my response t Eunice which deals witm more or less the same point.

Most Bremainers are missing the point.

There’s overwhelming agreement between Bremainers and Brexiters on one point – we don’t want to be part of the project. My – fairly extensive – anecdotal experience is that Bremainers reject that idea as vehemently as Brexiters. We were offered the choice of being half-out or wholly-out of the EU. When half-outers were asked why they thought we should be half-out the response was that they wanted to be close enough to pick cherries but sufficiently distant not to be involved in the car-crash. None ever expressed a reason other than venality.

The unappealing nature of the EU has far more explanatory value than the Bremoaner self-validating narratives currently doing the rounds. Fortunately, a majority were able to take a principled position.

There is not “overwhelming agreemen…that we don’t want to be part of the project”. I have never read such tosh in my life.Everyone in my extended family and personal friends voted for Remain with a real commitment to, and understanding ot the benefits of EU membership.

Your bizarre attempt to discuss the entire future of a country by mixed metaphor and incoherent analogy –picking cherries in a car crash — is redolent of the style of debate of brexiters. It is a narrative that has no basis in reality and is entirely founded on nationalistic and exclusionary right wing ideology. As a philosophical point, it is not possible to take a “principled position” on something when you have zero understanding of it and the ramifications of destroying it. The position taken is blind ideology — and this is where the self-righteous ignorance of the UK electorate has landed the country — in a situation where nobody has any vision for the future.

Indeed, it is you who are missing the point – and missing it quite spectacularly, too.

This is a fairly accurate analysis, in my view, but needs a lot more depth. In particular, some consideration of the extent and commonalities of growing euroscepticism across the EU would be useful. That could also encompass the strange and apparently “schizophenic” view of the EU that much of Eastern Europe seems to possess.

It could indeed be just the beginning of a series of vicious cycles as this model shows: https://www.know-why.net/model/CmQ4yt7ewpFtej_VVrNFmLA Taken from the model the biggest challenge is to let people feel the benefits of the EU and let even donor countries see their return on investment. On the other hand, if the return is made explicit it would raise new challenges …