The ongoing electoral cycle in Sub-Saharan Africa is turning out to be somewhat unusual. In the Nigeria March 2015 poll, the People’s Democratic Party suffered its first loss since the end of military rule in 1999, whilst in South Africa’s August 2016 municipal election the ruling Africa National Congress (ANC) registered its worst performance since the end of apartheid in 1994. Elsewhere, attempts to prolong the incumbent’s reign in Burkina Faso were forestalled by an eruption of protests in October 2014, bringing to an end Blaise Compaore’s 27-year rule. It would seem elections in the region are at a tipping point, the traditional incumbent re-election bias is at a historic low and the ground is fast shifting beneath the feet of the political establishment. What has triggered the turn of the tide?

Africa’s electorate: Of hope inflation and deflated realities

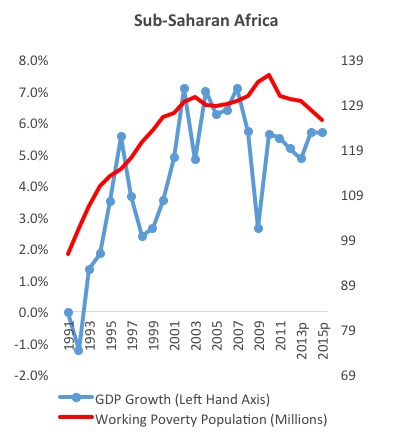

The 2000s commodity price upswing and successive downturn have conspired to ensure Africa’s electorate emerges from a decade of unprecedented hope inflation and near manic optimism, typified by the ‘Africa Rising’ narrative, to one of disproportionately deflated reality as most economies decelerate and some stagnate. Consider, for instance, that whereas between 2000 and 2015 East Asia and Latin America reduced the working poverty population (the share of workers living in households with consumption of less than USD 2.0 per day per person, according to the International Labour Organization) by 86.7 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively, sub-Saharan Africa has lagged behind its peers, reducing its own by a measly 0.6 per cent.

Source: International Labour Organization

When economic growth and labour productivity are at odds

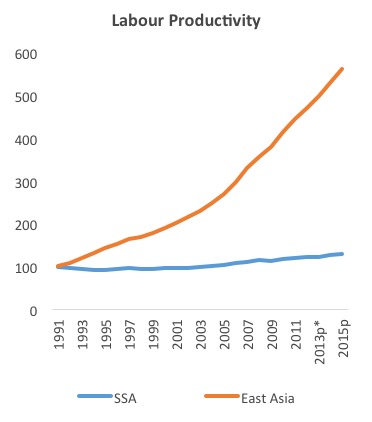

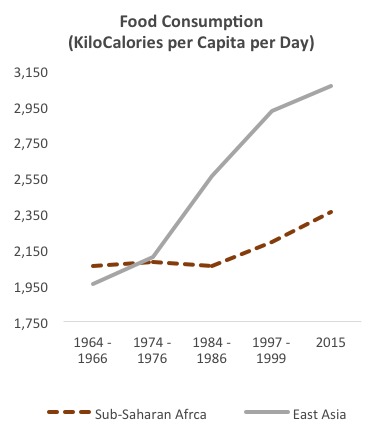

If a great deal has been done to put sub-Saharan Africa back on the growth ladder over the last decade, considerably less has been done to address labour market challenges in the region. Labour productivity, for instance, has been on a near flat-line over the last decade, growing by 35.2 per cent between 2000 and 2015 against East Asia’s 194.7 per cent (International Labour Organization). The sad narrative in this trend is that even at the best of times sub-Saharan Africa has been plagued by comparatively muted growth in labour productivity, creating a potential drag on long-term growth prospects. For a long time, robust high level economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa has camouflaged existence of this gaping disjoint with the labour market. For households, and voters in this case, however, this has translated into an unending grapple with depressed income levels, subdued spending power and below target socio-economic standards. It comes as the least of surprises, therefore, that the opposition party in South Africa, Democratic Alliance, wrested ANC off dominance in its traditional stronghold of Nelson Mandela Bay, a municipality that posts one of the highest unemployment rates, at 32 per cent, in South Africa.

1991=100 Source: International Labour Organization, Food and Agricultural Organization

Where do we go from here?

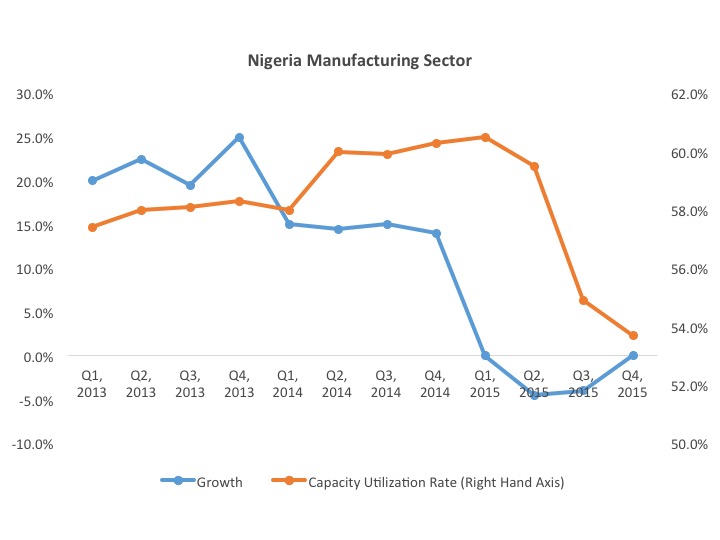

With Gabon, Ghana and Angola set to go the polls in August 2016, December 2016 and August 2017, it will be interesting to observe whether the trend witnessed in Nigeria and South Africa is replicated. The short-term imperative for sub-Saharan Africa is to ensure transition, where it happens, takes place in an environment of managed expectations. Most economies are bound to remain in austerity mode, as has been witnessed in the slash of fuel subsidies in Angola and Nigeria, in a bid to adjust to low commodity prices and see if growth remains lethargic in the near horizon. Even where effective policy is adopted, the typical lag between implementation and transmission effect could imply adverse economic conditions prevail through three or so quarters before paving way for improvement. The long-term imperative demands a policy mix that creates room for optimal utilisation of production capacity by addressing constraints such as infrastructure bottlenecks. Nigeria’s manufacturing sector, for instance, a potentially high productivity sector, has witnessed declining growth since 2013 on the back of low capacity utilisation (measure of potential output that is realised).

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Julians Amboko is a Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

Julians Amboko is a Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

This piece elucidates the nexus between the labour market challenges in Sub Saharan Africa and economic growth while drawing links to the electoral patterns. Nice piece Julians.

There is no doubt that the electoral cycles in Africa significantly affect the economic growth patterns.

This is a great presentation of the ‘why’ of differences between East Asia & SSA from a labour force angle. However, a comparison of SSA with poorer South Asian countries such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and (may be) India and their track records would also be interesting to look at.