Does Europe need saving and, if so, from what? The European Union has been immersed for too long in deep multiple crises. Is there one potential solution we can all agree and concentrate upon? I argue that such elusive factor is foreign direct investment. FDI can play this “silver bullet role” because of its powerful economic effects and of the capacity to support and amplify FDI inflows that marks deep EU integration.

For Europe, this is not a Great Recession, it is a Crisis Like No Other. It is a constellation of inter-related crises. Europe has experienced a financial crisis, a debt crisis, an economic crisis, a productivity crisis, a Greek crisis, a populism crisis, a terrorism crisis, a refugee crisis, a confidence crisis and a democratic deficit crisis, just to name a few. Yet this one is also, crucially, an investment crisis.

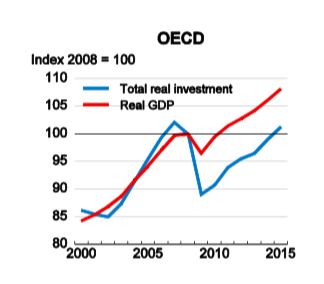

Looking at OECD countries since the turn of the century (the red line in the first chart) one may be tempted to ask: crisis, what crisis? The issue seems not to be how exceptional it is, but whether it has actually happened.

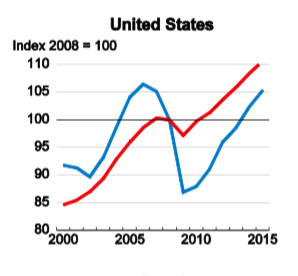

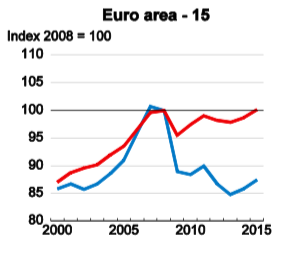

Figure 1. Real gross investment

Source: OECD (2015)

Real GDP declines in 2008 and 2009 but recovers quickly. True, investment (the blue line) somewhat unexpectedly decouples. However this still seems insufficient to fuel all the heated debates we witnessed.

The OECD may be a group of rich countries but it is heterogeneous. Looking at the US experience, the investment decoupling is evident but the recovery has been robust and one may even dare to say “normal.” It is when turning to the Eurozone that one can really make the case that this is a Crisis Like No Other. Investment seems a key actor and one that we may have started to pay attention too late in the play. This crisis is unique because it is about Europe and it is about investment.

If one remains unconvinced about the uniqueness of the crisis, enter Brexit. Brexit raises existential questions about the value of EU membership and about the dynamics of its benefits. On these, the Crisis Like No Other may actually have been positive. Before, we took for granted that those benefits existed but were too difficult to capture. Today, we debate instead their magnitude and how they change over time.

If benefits are robust, the next question is about mechanisms. How do countries benefit from EU membership? The usual suspects are trade, finance, and migration. Yet we may have made a big mistake by downplaying FDI.

Economic theory distils costs and benefits. FDI adds to the capital stock (particularly relevant in this Investment Crisis) and creates new jobs in the host economy. Underscoring its long-run impact on productivity, FDI facilitates access to new technologies and management techniques. A less well-known benefit from FDI is that it minimises structural reform reversals. Of course there are costs: competition from large foreign companies may bankrupt domestic producers, which may lead to job losses and/or low re-investment rates. It is however difficult to disagree that in theory the benefits outweigh the costs, by a margin.

Considering these net benefits, we would expect the evidence to be uncontroversial even accounting for errors in measuring FDI. The empirical evidence shows a positive effect of FDI on growth and productivity, but with important caveats. In one word, FDI is “conditional.”

On the macro or country level, the econometric evidence uncovers significant first-order effects and highlights thresholds. Countries benefit from FDI once they reached certain levels of human capital, of financial development and/or of institutional capacity.

At the firm and sectoral level, the evidence also uncovers significant first-order effects but stresses that the type of spill-over matters. FDI benefits upstream (suppliers) and downstream (customer) firms with much weaker evidence about benefits to firms in the same industry.

How binding are these conditionalities? A systematic assessment of the evidence concludes the economic impact of FDI is much less “conditional” than we often think. This based on a meta-analysis of about 1100 estimates, covering the full post-WW2 period, and focusing on countries under those thresholds (that is, those for which previous studies tend to find no robust effects). One explanation is that, below the thresholds, the difference between “macro” and “micro” effects is substantial (with the former about 6 times larger than the latter) while, above the thresholds, the difference between private and social returns is much smaller.

The feebleness of these caveats implies the economic impact of FDI is likely to be more robust than the available evidence indicates. The next question is then whether EU membership by itself can galvanise FDI inflows.

Most of the evidence focuses on the euro instead of EU membership and on trade instead of FDI. The seminal Rose Effect postulates that trade between two countries increases by 300 per cent once they share a common currency. Later refinements show that EU membership increases trade by about 135 per cent after 15 years (while EFTA membership only by 35 per cent) and that euro adoption causes an increase in FDI inflows of about 30 per cent. More recently, Glick and Rose criticise the evidence by showing that the estimated effect of a currency union on trade vanishes (that is, change from 300 to 0%) once modern and appropriate econometric techniques are used.

How much does EU membership raise FDI inflows? Although a dearth of answers to such questions remains, there has been some progress lately with the use of radically different methodologies producing strikingly similar estimates. Synthetic counterfactual evidence suggests that if the UK had not joined the Single Market FDI inflows would have been 25 per cent smaller. While gravity estimates show that EU membership raises FDI inflows by about 28 per cent and that this effect does not vanish due to estimator choice. FDI, differently from trade, survives the Glick-Rose critique.

In conclusion, Europe is undergoing a Crisis Like No Other, investment has been key, and multiple policy proposals are on the table. Many of these proposals are well-designed but have not received the priority (by which I mean the financial resources and political support) they require. Despite the long list, FDI has not yet figured prominently, if at all. The latest pieces of empirical evidence suggest that further thinking about the potential of FDI to help Europe overcome this Crisis is warranted. FDI can play a key role because of the robustness of its long-term productivity effects, which can be further supported by EU integration, and vice-versa.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is a summary of the author’s presentation at the The EU and FDI: Love Lost? Conference in Valletta on April 7th2017 in the context of the Maltese Presidency of the European Council. The author would like to thank Mario Brincat, Eva Rytter Sunesen, James Watson, Carlo Pettinato, Francisco Caballero-Sanz, Hinrich Voss, Christiane Stepanek-Allen and seminar participants for valuable comments and conversations. The author considers himself solely responsible for the views expressed above ‘as well as for all the remaining errors’.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Piazza Gae Aulenti, Milan, by Maurizio Colombo, own work, Public domain

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Nauro Campos is Professor of Economics and Finance at Brunel University London. He is also affiliated with ETH Zurich and IZA-Bonn. His main fields of interest are political economy and European integration. He has taught at the Universities of Bonn, Brunel, CERGE-EI (Prague), Newcastle, Paris 1 Sorbonne and Warwick. He was a Fulbright Fellow at Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore), a Robert McNamara Fellow at The World Bank, and a CBS Fellow at Oxford University. He is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the (Central) Bank of Finland, a Senior Fellow of the ESRC Peer Review College and was a visiting at the IMF, World Bank, European Commission, University of Michigan, ETH, USC, Bonn, UCL and Stockholm. From 2009 to 2014, he was seconded as Senior Economic Advisor/SRF to the Chief Economist of the Department for International Development.

Nauro Campos is Professor of Economics and Finance at Brunel University London. He is also affiliated with ETH Zurich and IZA-Bonn. His main fields of interest are political economy and European integration. He has taught at the Universities of Bonn, Brunel, CERGE-EI (Prague), Newcastle, Paris 1 Sorbonne and Warwick. He was a Fulbright Fellow at Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore), a Robert McNamara Fellow at The World Bank, and a CBS Fellow at Oxford University. He is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the (Central) Bank of Finland, a Senior Fellow of the ESRC Peer Review College and was a visiting at the IMF, World Bank, European Commission, University of Michigan, ETH, USC, Bonn, UCL and Stockholm. From 2009 to 2014, he was seconded as Senior Economic Advisor/SRF to the Chief Economist of the Department for International Development.