While income inequality is largely unavoidable, the magnitude of inequality in the US today is staggering. For context, CEO compensation in the 1960s was around 20 times more than the average American worker. Using the same metric, today’s CEOs are paid over 270 times more than the typical worker. Some analysts suggest that this massive gap between the rich and everyone else is a clear sign that the US economy is broken – only a handful of people at the top are benefitting from the system while the rest of the country lags behind.

But how does the American public understand this dramatic change in the income distribution over the last few decades? Are most people aware of growing inequality, or is the public too uninformed or too apathetic about inequality to recognize these economic changes? If people are aware of expanding income differences, where does this knowledge come from?

The answers to these questions are important because of what they tell us about the future of inequality in the US. The public’s understanding of inequality has the potential to play a significant role shaping the discourse surrounding the issue of inequality, who participates in discussions about issue, and how policy debates related to income differences evolve. But a public that is unaware or ambivalent about the state of American inequality is unlikely to emphasize income differences as an important political issue or insist on solutions that might address income disparities.

Diverging from those who suggest that most people are not very informed on the topic of inequality (see here and here for examples), my research finds that the public’s perceptions of income inequality overall is clearly linked to objective indicators of economic disparities. In other words, the public does a good job of understanding changes in inequality. This conclusion is based on a new measure I developed that tracks how the public’s perceptions of income inequality collectively change over time for nearly every state in the US. The measure was created using a fairly technical procedure, but the basic idea is that I collected every opinion survey I could find that asked if people believe “the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.” Then, all of the responses (over 50,000) were aggregated by state and year and adjusted to make sure the measure reflects each state’s demographics. The result is aggregate state opinion from 1987 to 2012 indicating the percentage of the public agreeing with the “rich are getting richer” statement.

So why focus on collective, or aggregate, public opinion, and why look at the states? First, examining aggregate trends in opinion is particularly useful when change in opinion over time is expected to be important. This is certainly the case with perceptions of inequality if we want to know whether citizens are responding to objective changes in income differences. Also, viewing aggregate opinion helps sort out systematic changes in perceptions of inequality from the non-systematic (or random) views that might be captured when asking people about inequality. Every person is not expected to have a reliable awareness of inequality, but these essentially random responses from those who are unaware will cancel out when opinion is aggregated.

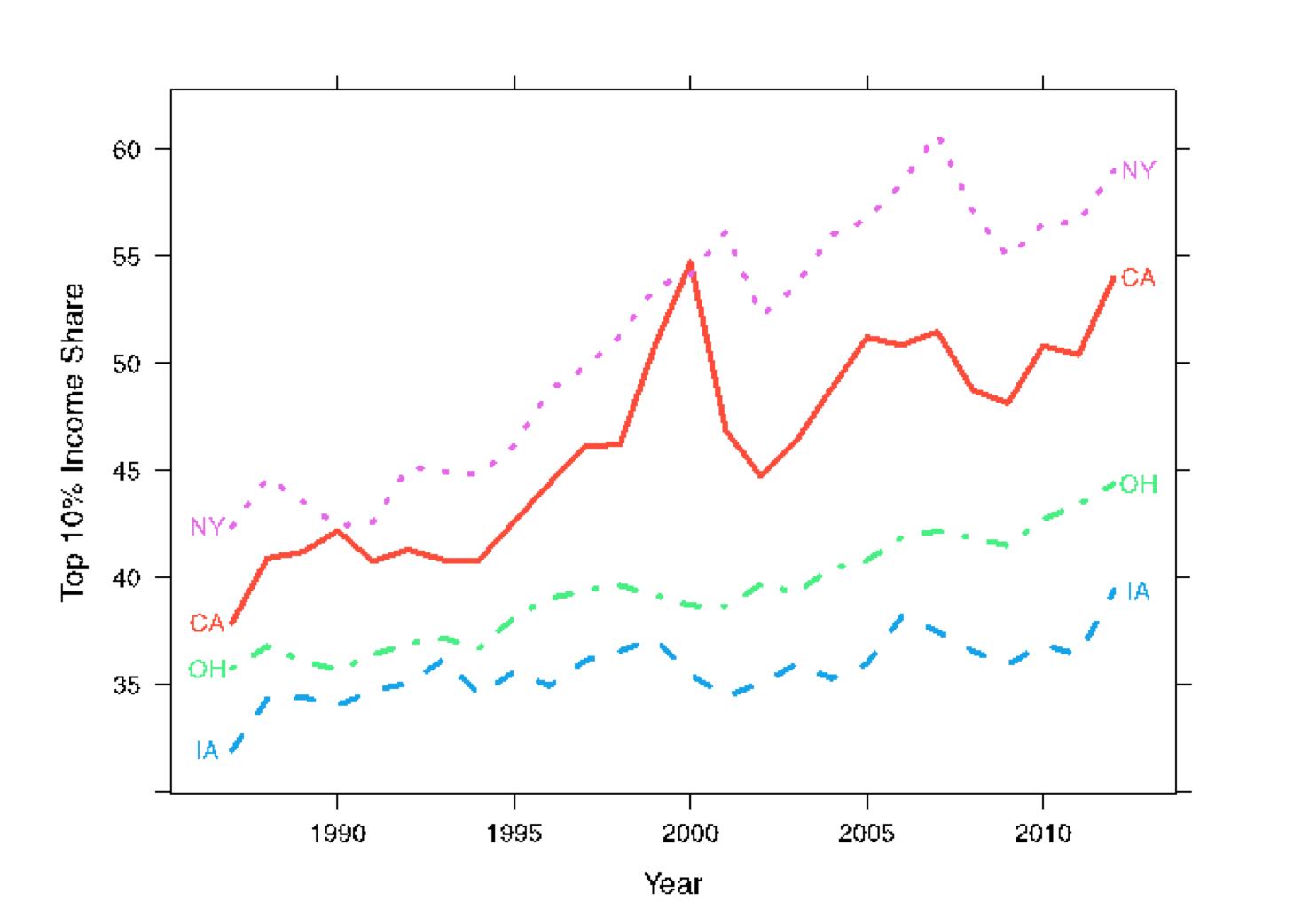

Second, most discussions of US economic inequality are concerned with how national income disparities have grown. There is nothing inherently wrong with this, but an exclusive focus on national inequality might limit our view of how the public understands changes in the gap between the rich and the poor. What many people might not realize is that the US states have produced quite different trends and changes in inequality. Figure 1 provides just a few examples of how state inequality can vary, showing over time trends in how much income is held by the richest 10 percent in each state (also known as top income share). States like Ohio and Iowa have experienced a steady climb in top incomes since the 1980s, but the overall growth of inequality in these states is relatively modest when compared the dramatic rise in inequality observed in states like California and New York. This suggests that experiences with income inequality can be shaped by the places where people live.

Figure 1. Changes in the top 10% income share in 4 states, 1987-2012

Source: The World Wealth and Income Database

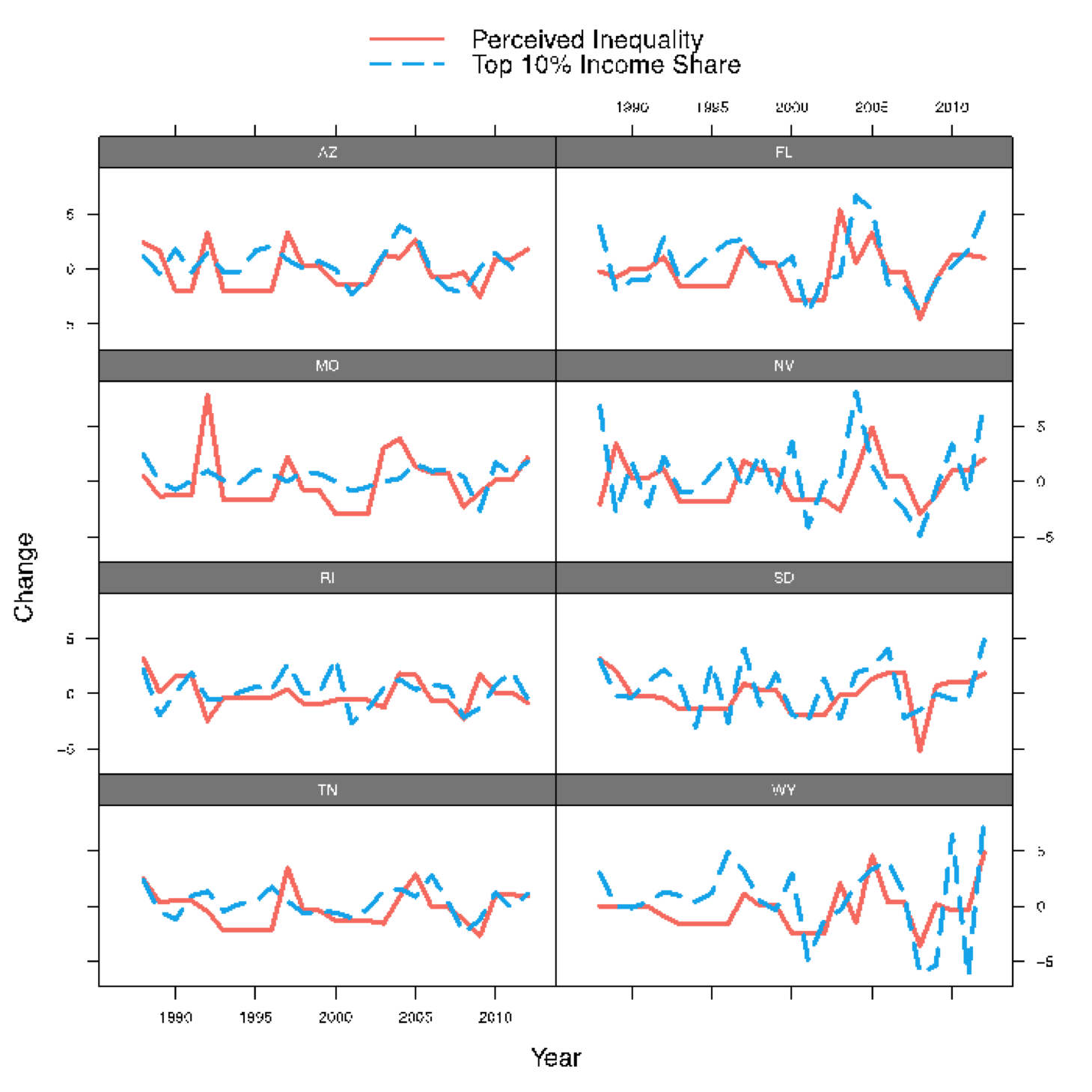

To get a sense of how the public collectively responds to over time changes in inequality, Figure 2 shows over time changes in observed income inequality (using the top 10 percent income share) and over time changes in the public’s perceptions of growing inequality for several select states (the measure I described earlier). The plot illustrates a remarkable association between changes in state top incomes (that is, whether actual inequality is growing) and changes in the perceived rise of inequality (that is, whether the public believes inequality is growing).

Figure 2. Changes in perceptions of growing inequality and top 10% income share in 8 states, 1987-2012

Source: Author’s calculations and the World Wealth and Income Database

Importantly, this relationship holds in more robust analyses that include all of the states and that account for a host of other economic and political factors that may affect views of inequality. The results show that collective perceptions of inequality are significantly shaped by measures of inequality like top income shares, as well as other indicators related to inequality like poverty and unemployment.

Of course, this does not mean that the public’s understanding of inequality is based purely on objective economic indicators. I also find that political context influences how the public views inequality, with changes in unemployment and poverty having a stronger influence on perceptions of inequality in more liberal-leaning states relative to those states that are more conservative.

These findings suggest that many Americans are taking note of the vast expansion of inequality that has taken place over the last few decades. Although awareness of inequality does not necessarily translate into demand for change, a more aware public is likely to set the stage for political action. In fact, in a new book that will be published later this year, my coauthor and I show that in states where residents perceive large inequalities they elect more progressive governments and the states adopt more policies that reduce income differences.

This focus on state inequality may lead some readers to ask if political changes at the state level are enough to alter the direction of inequality in the US. This is a fair point. Policy action from the federal government would probably have a more substantial impact on the income distribution. But with a historically polarized Congress that has done very little to address economic inequality over the last 40 years, the states may be the only path to a more equal future.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post was originally published on LSE USAPP.

- It is based on the paper ‘Understanding Public Perceptions of Growing Economic Inequality’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

- The post gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: DSC_8882, by Dean Chalim under a CC BY NC SA 2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

William W. Franko is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the John D. Rockefeller IV School of Policy and Politics at West Virginia University. His research examines the causes and consequences of political and economic inequality in the United States.

William W. Franko is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the John D. Rockefeller IV School of Policy and Politics at West Virginia University. His research examines the causes and consequences of political and economic inequality in the United States.