Corruption, the preferential treatment of connections, dependence on debt finance, and explosive borrowing from China have combined to push Sri Lanka into economic collapse. Political instability has only prolonged the crisis, provoking violence and unrest. Thamashi De Silva, Simon Commander, and Saul Estrin write that even if an acceptable caretaker government gets formed, the depths to which the economy has sunk, the degradation of institutions, and a sense of impunity among the elite will make recovery a protracted and painful process.

Rioting and deaths, chronic shortages of essential goods and fuel, erratic power supply at best or no power supply at worst, plummeting incomes, collapsing businesses, shuttered schools, debt default along with a collapse in reserves, topped now by hyper-inflation are but some elements of Sri Lanka’s present – and appalling – plight.

What is perhaps most striking is the country’s pace of economic descent, almost unprecedented outside of wartime. Over a quarter of the population now needs immediate humanitarian assistance. And the country will need at least $6 billion in external support in the coming six months alone.

Not surprisingly, the economic collapse has been accompanied by a profound political crisis. The Prime Minister – Mahinda Rajapaksa – was forced out of office in May. His successor – Ranil Wickremesinghe – has said he will step down, although when is unclear. And after huge pressure from the street, including an invasion of the Presidential compound, Gotabaya Rajapaksa – the country’s President – fled the country on 13 July.

This blog post outlines the nature of the collapse and the reasons behind it. Sadly, the present and sorry predicament of Sri Lanka is a chronicle well foretold.

How did Sri Lanka get here?

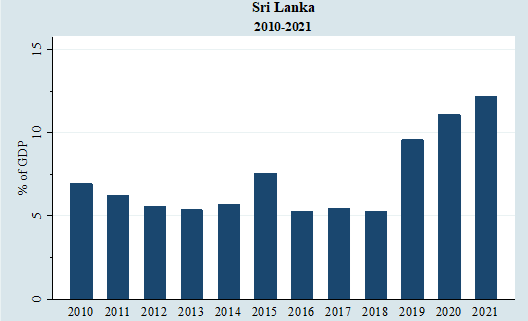

The near-term triggers to the present crisis have been a litany of poor recent policy choices. In 2019, following his election as President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s administration introduced swingeing tax cuts to personal and corporate taxation, as well as to VAT; the latter being slashed from 15% to 8%. The consequence was inevitably a dramatic and immediate decline in tax revenues (which were already at a low level ) from 11.6% in 2019 to 8.1% of GDP in 2020 (Central Bank of Sri Lanka). As shown in Figure 1, by 2021 the fiscal deficit had swollen to over 12% of GDP – roughly double what it had been in the five years pre-2019.

Sri Lanka’s foreign debt has also spiralled out of control. Already in the latter part of 2020, credit rating agencies had downgraded Sri Lanka to near-default status with the result that the country was largely excluded from international capital markets. Prior to that, the government had resisted any debt restructuring programme or help from the IMF. Yet, despite losing access to international capital markets, Sri Lanka continued to pay sovereign bondholders by drawing down foreign reserves, even settling a bond payment of $500 million in early 2022. In fact, it has been alleged that businessmen connected to the government benefitted from International Sovereign Bond payments as bonds were sold to them at a 50% discount even as they subsequently reaped a 300-400% return simply through quarterly interest payments. One commentator – Harsha de Silva – has alleged fraud committed in ISB payments (Daily FT, 20 April 2022).

Figure 1. Sri Lanka’s Budget deficit (2010-2021)

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Another ill-conceived measure that cut tax revenues significantly occurred in October 2020. The government drastically reduced the tax on sugar imports from October 2020 to February 2021. A subsequent investigation by the National Audit Office found that one of the main traders – Pyramid Wilmar – released stocks on the date the policy was announced, thereby gaining a massive de facto tax concession. The company also raised its monthly imports by over 1222% during this tax reduction period compared to monthly imports in the 9-10 months before the reduction. The owner of Pyramid Wilmar, Sajad Mawzoon, is understood to be a close confidant of the Rajapaksa family. Further, the investigation found that consumers did not benefit from the tax cuts as prices did not for the most part decrease. However, the Treasury lost about 16 billion Sri Lankan rupees (Rs) in tax revenues, equivalent to 1.3% of 2021 tax revenues and 4.3% of health expenditures (calculated based on the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s 2021 Annual Report).

In 2021, an ill-conceived and immediate prohibition on the import and use of chemical fertilizers led to a collapse in food production – notably rice, which fell by over 39% – and spiralling imports (Paddy Statistics, Department of Census and Statistics). The ban also led to a sharp contraction in both tea and rubber production, two of the country’s key exports and sources of dwindling foreign exchange. These egregious policy errors compounded the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that had decimated Sri Lanka’s prominent tourism industry, an industry already badly affected by the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings. As a consequence of the combined effects, GDP growth, which had averaged just over 5% per annum in the previous decade, turned strongly negative in 2020. In 2022 GDP is presently projected to decline by nearly 8% (and this estimate may well prove to be optimistic (Global Economic Prospects, June 2022).

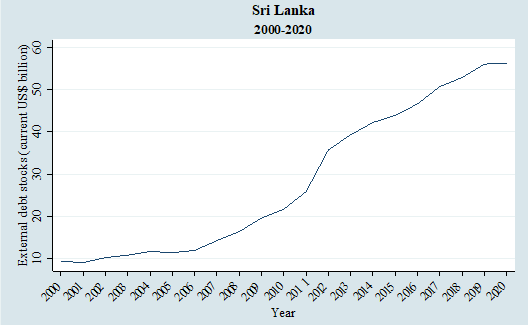

Yet, while recent policies have certainly aggravated the country’s economic plight, the current collapse also reflects the culmination of deeper, longer-term problems. A striking illustration of these can be seen in the way in which debt – domestic and external – has skyrocketed in the Rajapaksa era. The ratio of public debt to GDP jumped to 119% by 2021. External debt that stood at $11 billion in 2005 had surpassed $56 billion by 2020 – equivalent then to 66% of GDP. 15% of that was held by China (IMF Country Report, March 2022).

Figure 2. Sri Lanka’s total external debt stocks (2000-2020)

Source: World Development Indicators

Indeed, the emergence of China as a lender – particularly for infrastructure projects – has been a major feature of the last decades. Between 2005 and 2015, 70% of public infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka were funded and constructed by China (Foreign Affairs, May 23, 2016). These included the Norochcholai coal power plant, the Hambantota Port and International Airport, the Colombo International Container Terminal, and the Lotus Tower. Under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that was introduced in 2013, additional projects – including the Colombo Port City, the Southern Expressway and several other highway and water projects – have been funded (according to aid data that measures Chinese state-financed projects in various countries, China financed 163 projects in Sri Lanka between 2000 and 2018, totalling $13.8 billion).

The explosion in financing from China exposes two serious issues. The first concerns Sri Lanka’s ability to repay these loans. The second concerns how the money has been spent and the criteria whereby projects were selected. Both issues are illustrated by the way that Mahinda Rajapaksa’s plans for transforming his hometown, Hambantota, from a small fishing town into a major port and investment zone have been financed. Already, due to an inability to service debts, the Hambantota port has had to be ceded on a 99-year lease to China in 2017 (New York Times, June 25, 2018). Hambantota is now home to an empty airport (Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport), an empty cricket stadium (Mahinda Rajapaksa International Cricket Stadium), and an empty international conference centre. In the past eight years, the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport has had revenues of around Rs. 474 million and expenditure of over Rs. 14.4 billion (Sunday Times, June 5, 2022).

Sri Lanka has repeatedly sought loans from China for ‘white elephant’ projects in the Rajapaksa era, while at the same time rejecting grants and projects from other countries. For example, in 2020, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) discontinued a $480 million grant to Sri Lanka that was intended to upgrade the public transportation system in urban areas and improve land registration, due to lack of engagement from the government. However, the government has argued that the compact undermined Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and national security. In 2020, the Sri Lankan government also rejected a $1.5 billion light rail transit project funded by Japan for Colombo arguing that it was not cost effective. Yet, the Japanese loan had a 40-year repayment period with an interest rate of 0.1% (Newsfirst, 25 September 2020). However, many Chinese infrastructure projects, mostly for highways, have continued despite the pandemic and dwindling foreign reserves in recent years. And the average rate of interest for these Chinese projects has been around 3.2%, with an average maturity of 16.5 years (calculated using Aid Data’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0, which includes projects from 2000 through 2017, with 54 projects in Sri Lanka listing the interest rate).

A measure of the murkiness of the relationships between the Sri Lankan government and China can be gauged by the revelation in 2018 that large payments – approaching $8m – were made to Mahinda Rajapaksas’s 2015 reelection campaign by the Chinese port development fund (New York Times, June 25, 2018). In addition, the Colombo International Container Terminal Ltd., a company where 85% of the shares are owned by China Merchants Port Holdings Co. Ltd., made a payment equivalent to $150,000 to a Foundation controlled by Pushpa Rajapaksa, the wife of one of the most influential Ministers (Newsfirst, 13 July 2018).

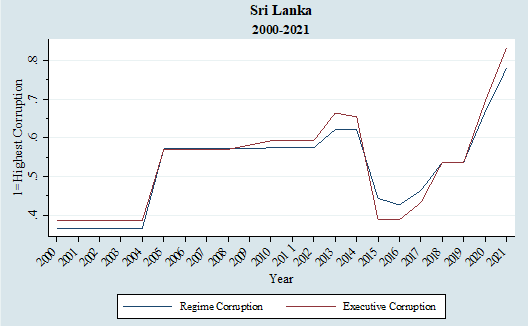

Since 2005, a significant increase in the incidence of corruption has occurred. For example, V-Dem compiles time-series measures of both regime and executive corruption. The first measures the extent to which politicians use office for private or party gain; the second measures how often members of the executive use their office to grant favours in exchange for bribes as well as embezzle. According to Figure 3, both indices show a sharp rise after 2004/5; a temporary abatement under the Yahapalanya government that was in power between 2015-2019, before rising yet further after 2019.

Figure 3. Sri Lanka regime corruption and executive corruption index (2000-2021)

Source: V-Dem.

In short, rising indebtedness and concern over the ability to service its external debt, a sharp deterioration in the country’s ability to export (exports of goods and services which accounted for around 35% of GDP in the early 2000s had collapsed to – and subsequently stayed at – around 20% by 2010), degraded governance, growing corruption and slowing growth were all salient features of Sri Lanka’s trajectory in the last decade and a half.

The house that the Rajapaksas built

To understand the deeper reasons behind the country’s plight, we need to understand how its political economy and associated governance has evolved since 2005. That was the year when the first member of the Rajapaksa family – Mahinda – was elected President. Except for 2015-2019, when they were voted out of office, the Rajapaksa family has controlled the main offices of state and levers of power in Sri Lanka. Between 2019 and May 2022, not only was Gotabaya Rajapaksa the president, but his brother, Mahinda, was the prime minister. Although some other countries have, or had, families controlling power, the extent to which the Sri Lankan state has been taken over by one family following elections is very striking.

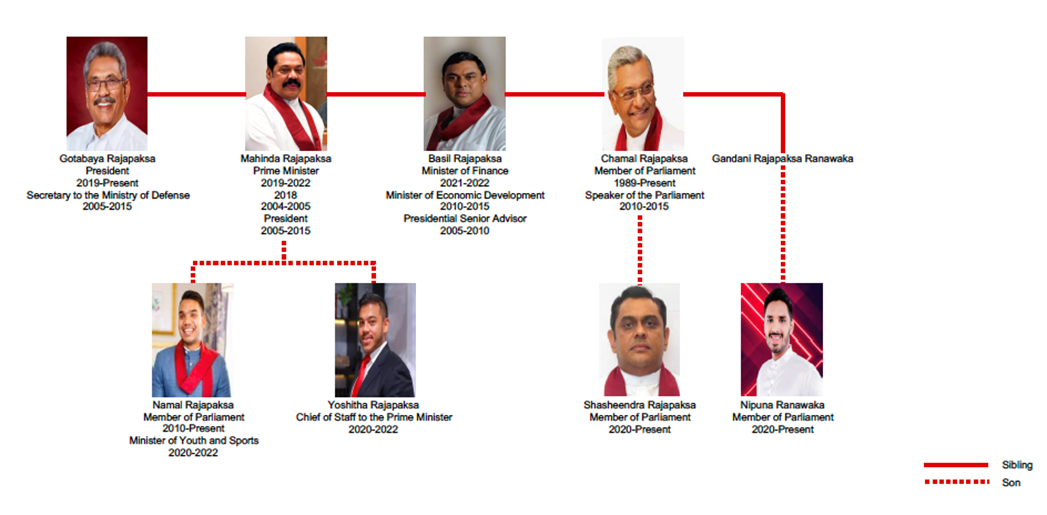

Figure 4. Rajapaksa family tree

Quite how striking is shown in Figure 4 which provides a family tree showing not only the two brothers that have, at various times, been elected as president, but also another brother – Basil – who, at various points, has been a minister – most recently, finance minister – and has also run their political party, Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP). Although Basil resigned from parliament in June 2022, his replacement – one of the richest businessmen in Sri Lanka – Dhammika Perera – has been a close associate of the family and was appointed the Minister of Investment Promotion in late June, although he has subsequently resigned. A fourth brother – Chamal – aside from being a member of parliament, was also speaker of the parliament between 2010 and 2015.

Figure 4 also shows that various of their children are members of parliament and have occupied ministerial or other senior government posts until very recently. Two of ex-Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s sons were his chief of staff and Minister of Youth and Sports. Other relations – cousins or in laws – also hold senior positions in the public sector. Figure 4 indicates how pervasive an infiltration into the broad machinery of government there has been by a single family.

If concentrating power in the hands of the family has been a hallmark of the Rajapaksas, the broader system of governance that they have fostered also displays a chronic reliance on networks of connections and patronage. That framework – rather predictably – has two principal components. The first comprises the public sector and the large number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The second comprises businesses and business groups that have forged close connections to individuals in government as well as their political vehicles.

A motley assembly of SOEs has been a cornerstone of the Sri Lankan economy. Numbering between 420 and 520, these companies have generally performed badly. For example, the 55 SOEs classified as strategically important by the government suffered a cumulative loss of Rs. 1.2 trillion between 2006 and 2020 (Advocata, 17 December 2021). The labour productivity of SOEs has declined substantially in the past decade, with their average cost of labour being around 70% higher than in private firms (Ginting and Naqvi, 2020). In addition, total SOE debt has climbed steadily from around 6.5% of GDP in 2012 to over 9% in 2020. Yet, there have been no substantive attempts at improving their financial performance or divestiture.

Indeed, in some instances, quite the reverse has happened. An egregious example of mismanagement has been Sri Lankan Airlines. Previously a profitable company managed by Emirates, it was re-nationalised in 2008. Since then, the company has not had a single year when it has been profitable, incurring a cumulative loss of Rs. 302 billion between 2009-2021 (Sri Lankan Airlines Annual Reports).

In general, SOEs have been attractive to politicians for the ability to distribute resources, jobs, contracts and other benefits for themselves and their coteries. This has certainly been the case in the Rajapaksa era. The other pillar of the Rajapaksa system has been local businesses and business groups. These have benefited not only from the way in which policies have been designed – for example the tax cut on sugar mentioned earlier – but also through contracts and preferential market access. While it is alleged that some businesses particularly close to the Rajapaksas have benefited significantly, it appears that most of the incumbent business groups have been able to secure their positions, not least through making accommodation with the government and ruling family.

The power of connections has also spilled across borders. The modern Indian exemplar of a politically connected business group – the Adani Group – has seemingly leveraged its close ties to India’s prime minister to help open doors in its neighbouring country.

In 2022 the Adani group signed two renewable energy projects in the north of the country (The Hindu, 13 March 2022 and Daily Mirror, 13 June 2022). This was facilitated by an Amendment to the Electricity Act that was passed in parliament, which eliminated competitive bidding for energy projects. Moreover, the chair of the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) appeared at the Committee of Public Enterprises (COPE) hearing in parliament and claimed that the president – Gotabaya Rajapaksa – told him that the Indian prime minister – Narendra Modi – was insisting that the 500 MW wind power plant project be awarded to the Adani Group (Newsfirst, June 11, 2022). This claim was denied and the chairman of the CEB then resigned.

This was not the first time that an Adani company gained a major contract where questions concerning due process and an absence of competitive bidding have been raised. That was in relation to the contract for a 35-year Build Operate Transfer (BOT) agreement to develop Colombo Port’s West Container Terminal. The contract was signed with Adani, local business group John Keels Holdings, and the Sri Lanka Port Authority in September 2021 with Adani holding a majority share. Interestingly, it has been alleged that the local agent involved in securing the deal between the Adani group and the Colombo Port was none other than Sajad Mawzoon, the owner of Pyramid Wilmar who, as mentioned earlier, benefited substantially from the cut in taxes on sugar in 2020 (Island, December 24, 2020).

While Adani and its partners got the contract for the west side of the Colombo Port, another local business group – Access Group – secured the contract for developing the east side in a joint venture with China Harbour Engineering. Access was founded in 1989 and has been one of the fastest growing business groups in Sri Lanka in recent years. As is common in much of Asia, it has exposure to multiple sectors and is composed of highly diversified components ranging, inter alia, from engineering and construction to healthcare, aviation, telecommunications and real estate. Parts of the business group – notably Access Engineering – appear to have benefited from their close connections to the Rajapaksas (Reuters, 29 March 2015). Indeed, when Mahinda Rajapaksa failed to be re-elected in 2015, the new government cancelled an $85 million airport runway project awarded to Access Engineering because according to the Ports and Aviation Ministry, “no competitive tender process had been followed in the award of the contract and Access Engineering lacked experience for the runway work” (economynext, 21 March 2015). The company explained this by claiming that the Rajapaksa government had decided to award the contract to local contractors.

Given the extent of corruption and mismanagement, talks with the IMF, as well as other donors, will have to deal with these issues. The United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee noted that “any IMF agreement with Sri Lanka must be contingent on independence of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, strong anti-corruption measures, and promotion of the rule of law.” It is clear that any new government will have to address not just past economic mismanagement but also introduce sweeping governance and anti-corruption reforms.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s descent into economic collapse and political upheaval can be traced to a number of factors – corruption and the preferential treatment of connections, excessive dependence on debt finance – not least the explosion in borrowing from China – as well as rank incompetence. This miserable combination is compounded by the inability so far to initiate a much-needed political transition. That political instability has only prolonged the crisis, provoking violence and unrest. The need of the hour is the formation of a national unity government and, in due course, elections. But there are political disagreements among the various parties, an antipathy to politicians on the street and, as a result, the risk of political paralysis. Further, even if an acceptable caretaker government gets formed, the depths to which the economy has sunk, along with the degradation of institutions and a sense of impunity among the elite, will make recovery a very protracted and hugely painful process.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared first on LSE’s Management with Impact blog. It draws in part on the authors’ research for their forthcoming book “The Connections World: The Future of Asian Capitalism”.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of the European Commission, LSE Business Review, or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by 8268513, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Very interesting read and good account of the chronology leading to default. Any thought on the road to recovery? How trade policy reforms can help in swift growth and back to normality?

Sri Lanka has 4 million Tamils,whose loyalty is to India,and who want to,and always wanted,to secede.

There was a 3 decades war,which drained the Sri Lanka economy – had Lanka set up the right manufacturing sector,in those decades – the nation would have been a superpower today.It is the land of Ravana,who flew Sita,the empress of Indiamin an AEROPLANE,and Rama took 12 years to make a bridge,to reach Lanka (with the bridge made by apes)

It was the RAW which funded and trained the LTTE,and has caused the ruin of Lanka.RAW also interfered in the Lanka elections and Presidential selection,on many times.It had INT,on the “almost successful assassination”

of Gen Fonseca (but did not tip off the Lankan INT)

HAD THE WAR NOT TAKEN PLACE – LANKA WOULD HAVE SAVED BILLION IN USD IN WAR MONEY AND ALSO EARNED BILLIONS IN USD IN INDUSTRIAL GROWTH

Companies go bust NOT due to the secured loans of 5-10 years – which are secured by English & Equitable Mortgages – but by the UNSECURED LOANS which are of short tenors & Floating ROI

Lanka is in the same hole

It was sunk by the ISB – Euro Bonds – which were taken after the 2009 war was over.It was rolled over & the party went on – just like LC roll overs.Then the downgrades of Lanka happened,& ROLLOVERS STOPPED – & the, COVID,& the CHEMICAL FERTILISER BAN

Lanka Debt to GDP is 120 %

Lanka Foreign debt to GDP is 50%

Lanka Tax to GDP is 8% =

Lanka has 1 Billion in FX & 13 Billion of ISB & 8 Billion of ISB in 12 months as due for payment

Lanka exports are doomed

Lanka has food shortages

Lanka depleted Billions of USD to defend the SLR – which led to loss of remittances

The Disasters of Gotabaya

Banning Chemical fertilisers – which led to dramatic declines in rubber and plantation yields,and rice and other food crops – which in turn,led to food shortages,crash in exports and expensive food imports and loss of FX – He says that it was done to SAVE FX ! (Who gave him that advice)

Slashing VAT by half and lowering Taxes on incomes

Making up loss of tax revenues by ISB of short tenor and high ROI

Using FX reserves to pay off ISB

Sugar and Coconut Oil Import duty scam to benefit his pets

USING PRECIOUS FX TO DEFEND THE SRI LANKAN RUPEE – WHICH SHOULD HAVE BEEN ALLOWED TO COLLAPSE A LONG TIME AGO

BUT THE REAL DISASTER WAS THE FERTILISER BAN WHICH CAUSED FOOD IMPORTS AND REDUCTION IN PLANTATION EXPORTS – IN A COVID TENOR – WHEN TOURISM WAS DOWN

AND THIS COULD NOT HAVE BEEN HIS IDEA !

The empty stadiums,empty roads,empty airports,empty towers – yield no income – but are financed by 20 year loans at 10 to 320 BP ROI.Even the 500 Million USD loan of ISB repaid by Lanka,WAS BOUGHT IN OFF MARKET TRADES,AT 50% OFF THE PAR VALUE (BEFORE THE REDEMPTION).

PRC CANNOT WAIVE THE LOANS OR SWAP INTO EQUITY AS ALL OTHER NATIONS WILL ALSO DEMAND THE SAME WAIVERS

LANKAN CRISIS IS A HYBRID ASSYMETRIC WAR AGAINST PRC – SILK ROUTE & BRI – TO DESTROY THE PRC INVESTMENTS – & FORCE CHINA TO DO DEBT WAIVERS OR EQUITY SWAPS. (SAME FOR ATTACKS ON CHINESE IN PAKISTAN).dindoohindoo

If there is NO TURNAROUND OPTION on the table – then NO ONE WILL LEND ANY MONEY – ONLY OPTION IS GRANTS – WHICH ALSO,DID NOT COME – FROM THE INDIANS !

Had Lankans stuck with the Chinese – this fiasco would NOT HAVE HAPPENED – AS PRC WOULD HAVE ENSURED THE LANKAN SUCCESS – AS IT WOULD HIT THE SILK ROAD INITIATIVE & THE PRC INVESTMENTS,IN AFRICA.PRC is a MAHAYANA state & Lanka is a Theravada state – the common link is Buddhism.India destroyed & exterminated Buddhists 1500 years ago.

THE INDIANS CONNED THE LANKANS,TO PART WAYS WITH PRC – & THE RESULT IS WHAT YOU SEE TODAY.HAD THE PLN DOCKED ITS NUKE SUBS & SHIPS AT LANKA – THEY WOULD HAVE ENSURED THE SUCCESS OF LANKA

Lankans need to read history ! Some gems from the Mahabharata

“Yama & all the Demons”, are in South India & Lanka – as per the Mahabharata, Book 13: Anusasana Parva: Section XCVII

He should make sacrificial offerings in due order; to Yama in the Southern region

Great article which I relied on heavily in writing “Sri Lanka Should Cancel Not Renegotiate Corrupt Loans.

An excellent essay – though the closing political analysis has been overtaken by events, the long-standing patterns of governance dysfunction and corruption remain in place. And signs to date suggest the IMF and other international partners of Sri Lanka are not yet determined to insist on the robust anti-corruption measures needed to change the game in a significant way. My one critique of the essay is there is no mention of the contributing role of high-interest and short-term international sovereign bonds in Sri Lanka’s debt crisis. It’s not only China and the Rajapaksas and the Sri Lankan political system/class that is to blame: mostly western hedge funds and other creditors have exploited the country’s weakness and many are likely to make a profit, even if a “haircut” is agreed through debt restructuring talks.

more of a political essay rather than a factual one even quoting corrupt opposition politicians like harsha de silva famous for his VW antiques and bond scam. Hilarious claim is that tax cuts caused the lankan crisis, ignoring country was at a recession by late 2018, and was in a debt crisis created by the previous yahapana govt. And the prudent thing for the 2020 new govt was to stimulate the economy with tax incentives and go back to growth which they achieved by 2021 even under a pandemic with no tourism and remittance contribution. And monthly tax returns shows by start of 2022 with economy expanding again the revenues were reaching prepandemic levels monthly.