The Rowntree management conferences are a unique repository of thinking about management in general and British management in particular. Held over a span of nearly twenty years, they encapsulate a certain strand in management thought that, unlike many other contemporary management theories, was liberal, human-centred and forward-looking. They are an experiment – tried once and never really repeated – in trying to carve out a peculiarly British approach to management thinking and practice.

The conferences were the brainchild of Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree, director and, from 1923, chairman of Rowntree. He was of course a Quaker, and his ideas are often discussed in the context of ‘Quaker capitalism, the business model based on social responsibility and philanthropy characterised by Quaker business families such as the Rowntrees, Cadburys and Frys. But there was much more to Rowntree’s philosophy of management than simple philanthropy. He was also running a business an intensely competitive industry – especially after the First World War – and under pressure to run that business efficiently and well. He knew that most of his fellow industrialists were in the same boat.

Soon after the war, Rowntree visited Boston and met with some of the more progressive thinkers in American management, including Henry Dennison and the brothers Edward and Lincoln Filene, who were actively encouraging their fellow business leaders to come together and share knowledge. This idea resonated with Rowntree, who decided to develop something similar in Britain. The first result was the Rowntree conferences, initially held at various locations two or three times a year, mostly in the north of England. These early conferences were low-key affairs, often without big names as speakers.

After 1921, however, the conferences found a permanent home at Balliol College, Oxford, and the star names began to arrive. Leading centre and left-wing economists included Graham Wallas, G.D.H. Cole and Sidney Webb, as well as several close associates of John Maynard Keynes. Political leaders ranging from Liberal imperialists like Lionel Hichens, the chairman of Cammell Laird, to Labour party stalwarts like J.R. Clynes and Arthur Greenwood spoke too, and Rowntree was assiduous in inviting leaders figures from the trades union movement to explain their position to the managers of capital. Scientists, including the psychologists Frederic Bartlett and C.S. Myers helped delegates try to understand the human side of business. Historians and social scientists added further context, and clergymen such as Robert Hyde and the charismatic American Rufus Jones added a religious element. While most of the speakers were British, we have identified at least ten Americans including Dennison and the great social scientist Mary Parker Follett.

Individual conferences were often themed around individual issues, such as the fascinating conference of 1923 in which papers addressed the issue of eliminating waste; still a hot topic today. Others were more general. The list of papers at one conference in 1924 is illustrative:

- The economic consequences of modern political thought

- Scientific salesmanship as a factor in regularising the demand for goods

- Industrial peace

- Need movement study dehumanise industry?

- Can the severity of cyclical waves of trade depressions be lessened?

- Industry as a service

- Controlling production within the factory

- The mental process of responsible decision making

Taken together, they show us what Rowntree and his contemporaries were thinking about, and we can also see what they were hoping to achieve. We can divide their aspirations into two categories: to develop a better way of managing, with more efficient and effective methods and practices, and to spread knowledge of that better way as broadly as possible. It should be added that many of the papers remain relevant today; indeed, Mary Parker Follett’s paper on leadership is one of the all-time great papers on the subject.

To many writers, then and now, scientific efficiency and social responsibility represent a paradox; businesses can have one or the other, but not both. It is quite clear that Rowntree himself did not believe this, and nor did most of those who spoke at the conferences. Paper after paper rams home the point that what we would now call social responsibility is in fact good business. Firms that treat their employees well and fairly, that engage with and talk to and motivate their employees, that see businesses ultimately as human organisations full of people with aspirations and hopes and dreams of their own, tend also to be firms that do well commercially. Business is a human activity; it is part of the fabric of civilisation. Rejecting the far-left ideal of abolishing private capital and markets, the Rowntree speakers argued instead that capitalism needs to sit down, take a good long look at itself, and remember what its primary purpose is: the creation of wealth, not just for a privileged few, but for everyone.

Rowntree and his colleagues were also missionaries. Far from keeping their ideas to themselves, they wanted to spread them as widely as possible. The conferences were exercises in proselytisation. While America and France both had business schools to generate and spread new ideas, such institutions were lacking in Britain. Apart from a few isolated institutions like the Faculty of Commerce at Birmingham, virtually a one-man band on the part of William Ashley, there was no formal management education in Britain. Urwick’s description of Rowntree as a mini-university is apt. He and his colleagues were stepping into the gap which universities and business schools should have filled.

Today, as mechanistic styles of management begin to look increasingly out of date, and the Fourth Industrial Revolution begins to make new demands on management, there is a similar groping around for new ideas, new ways of conceptualising the role and task of the manager. What first drew me to the Rowntree conferences was the notion that in many of these papers, Rowntree and his colleagues had already found part of the answer. Perhaps Rowntree, Urwick, Sheldon and the others were ahead of their time. Perhaps in the 1920s, a world still traumatised by the impact of the machine age – in the workplace as well as on the battlefield – simply was not ready for their message. I’m not sure it is ready yet today, either. But – perhaps – tomorrow they might be. It must be that one day soon, ‘Rowntreeism’ will find itself to be an idea whose time has come.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post draws from the ESRC funded project, ‘The Rowntree Business Lectures and the Interwar British Management Movement’.

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

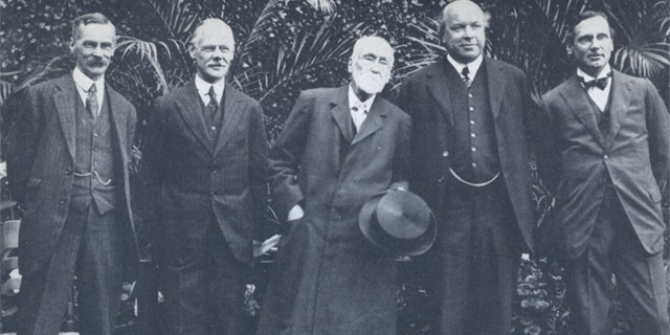

- Featured image credit: Photo of the late Mr. B.S. Rowntree (second from left) photographed with his father, the late Mr. Joseph Rowntree (centre) and (reading from left to right) the late Mr. Joseph Stephenson Rowntree (his brother), the late Mr. Arnold S. Rowntree (his cousin) and the late Mr. Oscar F. Rowntree (his brother). by Topical Press Agency Ltd, London, with no known copyright restrictions

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Morgen Witzel is an internationally known writer, lecturer and thinker on the problems of management. His 23 books have been published in numerous languages and have sold more than 100,000 copies worldwide. He has published more than 4,000 articles in publications including the Financial Times, Financial World, The Smart Manager, EFMD Global Quarterly and many others.

Morgen Witzel is an internationally known writer, lecturer and thinker on the problems of management. His 23 books have been published in numerous languages and have sold more than 100,000 copies worldwide. He has published more than 4,000 articles in publications including the Financial Times, Financial World, The Smart Manager, EFMD Global Quarterly and many others.

Alan Booth is an economic and business historian whose interests have ranged from history of economic thought to the automation of British industry in the 20th century. He has published extensively on the British economy since 1900 and on the impact of US ideas on British manufacturing and services.

Alan Booth is an economic and business historian whose interests have ranged from history of economic thought to the automation of British industry in the 20th century. He has published extensively on the British economy since 1900 and on the impact of US ideas on British manufacturing and services.

Rachel Pistol is a social historian whose research focuses on Second World War internment in the UK and USA, immigration history, historical memory, philanthropy, and the commemoration and preservation of historical sites. She has appeared on the BBC and Sky News, and has articles in The Independent, Newsweek, and The Huffington Post.

Rachel Pistol is a social historian whose research focuses on Second World War internment in the UK and USA, immigration history, historical memory, philanthropy, and the commemoration and preservation of historical sites. She has appeared on the BBC and Sky News, and has articles in The Independent, Newsweek, and The Huffington Post.