A growing number of companies claim to place a high priority on the wellbeing of their workers – and there is a fast-growing industry of firms selling products related to employee wellbeing. But does investing in employee wellbeing actually lead to higher productivity and are there any tangible benefits to the business bottom line? Experimental evidence such as Oswald et al (2015) suggests that the answer is yes, but until now, real-world evidence has largely been missing.

To begin to answer this question more systematically, we collaborated with the analytics and advisory company Gallup to look into its client database. Gallup has been gathering data on employee wellbeing, alongside productivity and firm performance outcomes, since the mid-1990s.

We conducted a meta-analysis of 339 independent studies accumulated by Gallup, including the wellbeing and productivity of 1,882,131 employees and the performance of 82,248 business units, originating from 230 independent organisations across 49 industries in 73 countries.

Higher employee wellbeing is associated with higher productivity and firm performance

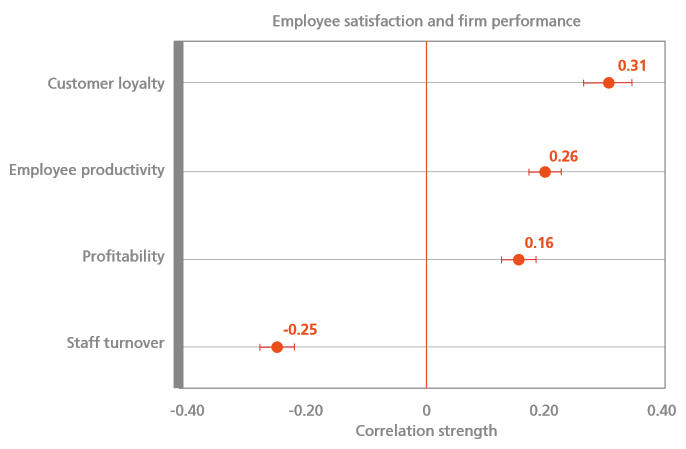

Figure 1 presents our main finding, showing correlations between employee wellbeing, employee productivity and firm performance across all industries and regions. Employee wellbeing is measured using a single-item five-point Likert-scale question that asks respondents ‘How satisfied are you with your organisation as a place to work?’ with answer possibilities ranging from one (‘extremely dissatisfied’) to five (‘extremely satisfied’).

Figure 1. Correlation between employee satisfaction, productivity and firm performance (Gallup client database, 95% confidence intervals)

Notes: The figure plots adjusted average correlation coefficients between employee satisfaction and different performance outcomes originating from a meta-analysis of 339 independent studies that include observations on the wellbeing of 1,882,131 employees and performance of 82,248 business units.

We focus on four key performance indicators that are arguably the most important for business:

Customer loyalty, where measures include fairly standard customer loyalty metrics, such as the likelihood of recommending or repurchasing a product or service, the ‘net promoter score’ or simply the number of repeated transactions.

Employee productivity, where measures include mostly financial indicators, such as revenue or sales per person, growth in revenue or sales over time, quantity per time period, labour hours or performance ratings.

Profitability measures, including the percentage profit of revenue or sales, or the difference between current profit and budgeted profit or profit in the previous time period.

Staff turnover, defined as the percentage of (voluntary) turnover per business unit.

We find employee satisfaction to have a substantial positive correlation with customer loyalty and a substantial negative correlation with staff turnover. The correlation with productivity is positive and strong. Importantly, higher customer loyalty and employee productivity, as well as lower staff turnover, are also reflected in higher profitability of business units, as evidenced by a moderately positive correlation between employee satisfaction and profitability.

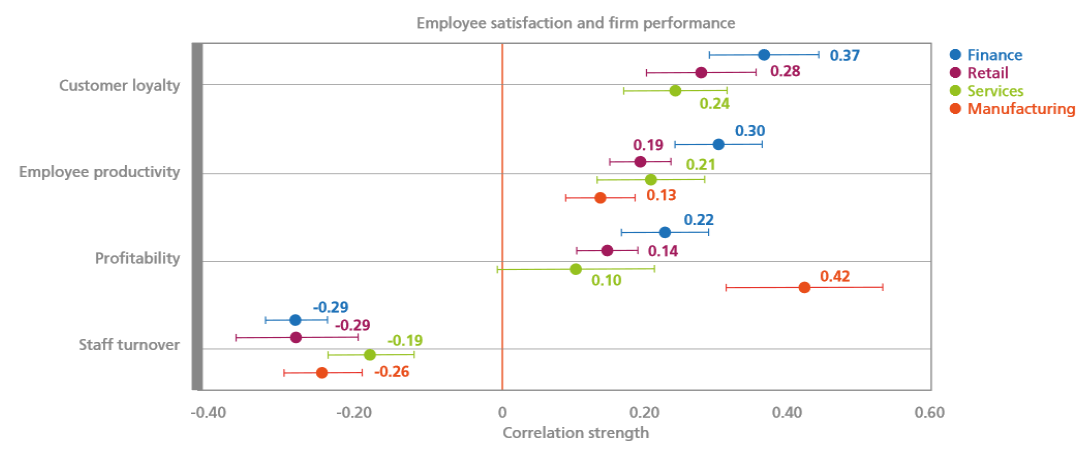

Some differences between industries, little between regions

Correlations differ somewhat by industry. Figure 2 shows correlations between employee wellbeing, productivity and firm performance by industry, distinguishing finance, retail, services and manufacturing sectors.

For most outcomes – customer loyalty, staff turnover and employee productivity – employee satisfaction is most important in finance, followed by retail and then, closely, by services. The correlation between employee satisfaction and business unit profitability appears to be somewhat stronger in the finance industry than in other industries, except manufacturing.

In fact, for manufacturing, we find that employee satisfaction has the weakest correlation with employee productivity, but the strongest with business unit profitability among all industry sectors. Note, however, that the 95 per cent confidence bands between industries are largely overlapping, pointing towards the universal importance of employee wellbeing across industries. We find little evidence for differences between firms based in the United States and other parts of the world.

Our analysis suggests a number of potentially fruitful avenues for future research. One potential reason for the particularly strong link between wellbeing and productivity in finance may have something to do with working conditions in that sector, in particular relatively higher stress and lower work-life balance, which potentially outweigh positive benefits of higher pay. This suggests that there is more room in the finance industry for employee wellbeing to raise productivity than in other sectors.

Manufacturing is highly focused on process efficiency and safety as primary metrics within plants, which relate directly to costs. Job attitudes are likely to relate to discretionary effort, which then affects quality, efficiency and safety within manufacturing plants and teams, possibly explaining the higher correlation between employee satisfaction and business unit profitability in that sector.

Why would higher employee wellbeing lead to higher productivity?

Of course, from this meta-analysis alone, we cannot make any strong causal claim about the effects of employee wellbeing on productivity or firm performance. But there is both a theoretical and an empirical body of research that points in this direction. Human relations theory states that higher employee wellbeing is associated with higher morale, which, in turn, leads to higher productivity (Strauss, 1968). Conversely, expectancy theories of motivation postulate that employee productivity follows from the expectation of rewards (including higher wellbeing) generated by eliciting effort (Lawler and Porter, 1967; Schwab and Cummings, 1970).

Emotions theory argues that employees’ emotional states affect their productivity (Staw et al, 1994), and in particular, that positive emotions lead to heightened motivation and hence better job outcomes and organisational citizenship (Isen and Baron, 1991*). A further channel is through positive, stimulating arousal, which can result in more creativity (Isen et al, 1987) or positive changes in attitudes and behaviour (Baumeister et al, 2007). In line with these predictions, Oswald et al (2015) show in a laboratory experiment that increases in wellbeing are strongly associated with increases in productivity of up to 12 per cent in a real effort task with incentives. In another study, De Neve and Oswald (2012) find that individuals who reported higher levels of life satisfaction at ages 16, 18 and 22 have significantly higher levels of earnings later in life. This holds even when comparing siblings and holding constant a wide range of observables, including education, intelligence, physical health and self-esteem.

Employee wellbeing also seems to pay off on the bottom line of business: Edmans (2011, 2012) studies the relationship between employee satisfaction and long-run stock market returns using a value-weighted portfolio of the ‘100 Best Companies to Work for in America’. He shows that during the period from 1984 to 2011, these companies had between 2.3 and 3.8 per cent higher returns than the industry average.

Figure 2. Correlation between employee satisfaction, productivity and firm performance, by industry(Gallup client database, 95% confidence intervals)

Notes: The figure plots adjusted average correlation coefficients between employee satisfaction and different performance outcomes, by industry, originating from a meta-analysis of 339 independent studies that include observations on the wellbeing of 1,882,131 employees and performance of 82,248 business units.

Concluding remarks

Our work is suggestive of a strong, positive correlation between employee wellbeing, productivity and firm performance. The evidence base is steadily mounting that this correlation is in fact a causal relationship (running from wellbeing to productivity). But clearly there is a need for more field and/or natural experiments in real-world firm settings in order to make a clear business case for improving employee wellbeing.

This calls for more consistent measurement of employee wellbeing in firms, alongside productivity and firm performance outcomes. In earlier work, we suggest that interventions aimed at raising productivity should target the key drivers of wellbeing at work, such as social relationships, making jobs more interesting and improving work-life balance (Krekel et al, 2018).

These interventions should be rigorously evaluated (ideally by randomised controlled trials) and costs should be reported to identify the most cost-effective ways of raising employee wellbeing, productivity and, ultimately, firm performance.

* Alice Isen and Robert Baron (1991) ‘Positive Affect as a Factor in Organizational Behavior’, Research in Organizational Behavior 13: 1-53

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post was published originally on CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).It summarises the authors’ “Employee Wellbeing, Productivity and Firm Performance“. CEP Discussion Paper No. 1605

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image courtesy of DesignRaphaelLtd, NOT under Creative Commons, All Rights Reserved

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Christian Krekel is an assistant professor in behavioural science at LSE’s department of psychological and behavioural science, a research officer in CEP’s wellbeing programme, and at the University of Oxford’s Wellbeing Research Centre. He is an applied economist. His research fields are behavioural economics and wellbeing, policy and programme evaluation, and applied panel and spatial analysis. He obtained his PhD in economics from the Paris School of Economics.

Christian Krekel is an assistant professor in behavioural science at LSE’s department of psychological and behavioural science, a research officer in CEP’s wellbeing programme, and at the University of Oxford’s Wellbeing Research Centre. He is an applied economist. His research fields are behavioural economics and wellbeing, policy and programme evaluation, and applied panel and spatial analysis. He obtained his PhD in economics from the Paris School of Economics.

George Ward is a research associate in CEP’s wellbeing programme and a PhD student in behavioural and policy sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is based at the Institute for Work and Employment Research, MIT Sloan School of Management. His work aims to combine insights from economics, psychology and political science, and focuses primarily on the study of human happiness and wellbeing.

George Ward is a research associate in CEP’s wellbeing programme and a PhD student in behavioural and policy sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is based at the Institute for Work and Employment Research, MIT Sloan School of Management. His work aims to combine insights from economics, psychology and political science, and focuses primarily on the study of human happiness and wellbeing.

Jan-Emmanuel De Neve is an associate professor in economics and strategy at Saïd Business School, a fellow of Harris Manchester College at the University of Oxford, and a research associate in CEP’s wellbeing programme. Jan’s research interests are in behavioural economics and political economy. The underlying theme throughout his research is the study of human wellbeing. This ongoing research agenda has led to new insights in the relationship between happiness and income, economic growth, and inequality. Significant new findings have also been published on the objective benefits of subjective wellbeing and in uncovering the genetic architecture of human wellbeing. He obtained his PhD from the LSE and was a Fulbright scholar at Harvard University.

Jan-Emmanuel De Neve is an associate professor in economics and strategy at Saïd Business School, a fellow of Harris Manchester College at the University of Oxford, and a research associate in CEP’s wellbeing programme. Jan’s research interests are in behavioural economics and political economy. The underlying theme throughout his research is the study of human wellbeing. This ongoing research agenda has led to new insights in the relationship between happiness and income, economic growth, and inequality. Significant new findings have also been published on the objective benefits of subjective wellbeing and in uncovering the genetic architecture of human wellbeing. He obtained his PhD from the LSE and was a Fulbright scholar at Harvard University.

Dear Sirs,

Many thanks for this very interesting review. Regarding the situation in the manufacturing sector, does it make sense to think

– that engineers have (through lean management, six sigma, etc.) very much reduced the impact of human performance on productivity? In other words, that productivity is much more dictated by e.g., machine failure than by employee well-being?

– that employees who do not feel well will therefore not lower their productivity, but rather take sick leave days and change jobs, hence the impact on business unit profitability?

Best regards,

O. Girard