The World Health Organization has declared a global pandemic as the coronavirus spreads rapidly across the world. As tumbling stock markets reveal growing fears about the potential economic impact, we invited US and European economists to express their views on the likelihood of a major recession. We also asked them about the relative importance of the supply and demand channels through which COVID-19 is affecting and will affect the economy.

We asked the experts whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements, and, if so, how strongly and with what degree of confidence:

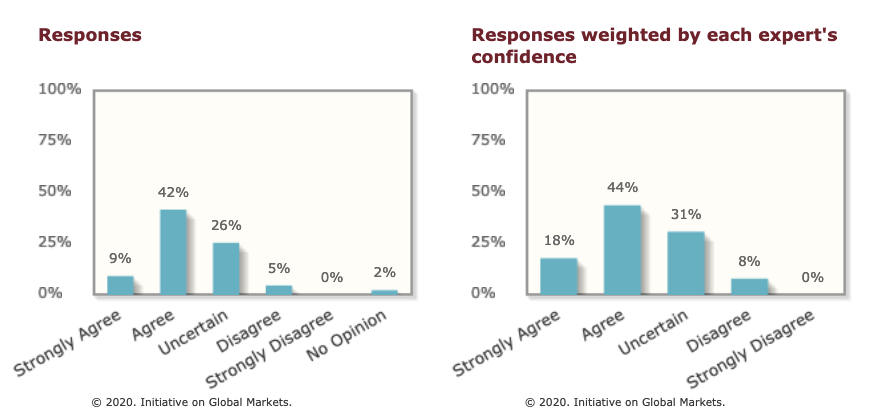

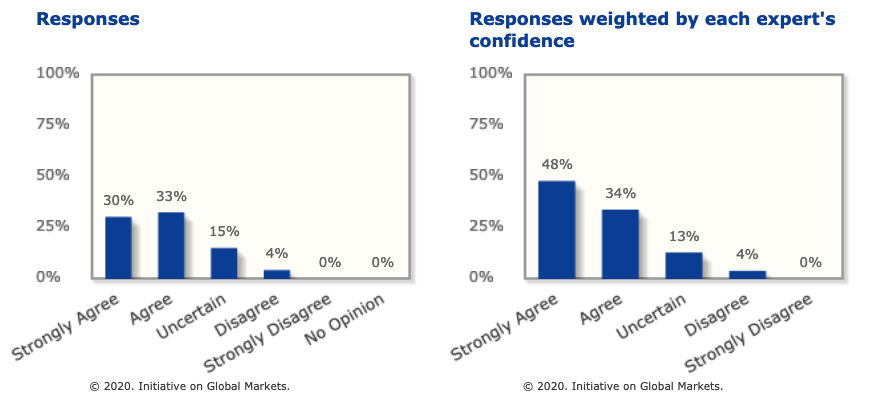

A. Even if the mortality of COVID-19 proves to be limited (similar to the number of flu deaths in a regular season), it is likely to cause a major recession.

Source: IGM Economic Experts Panel

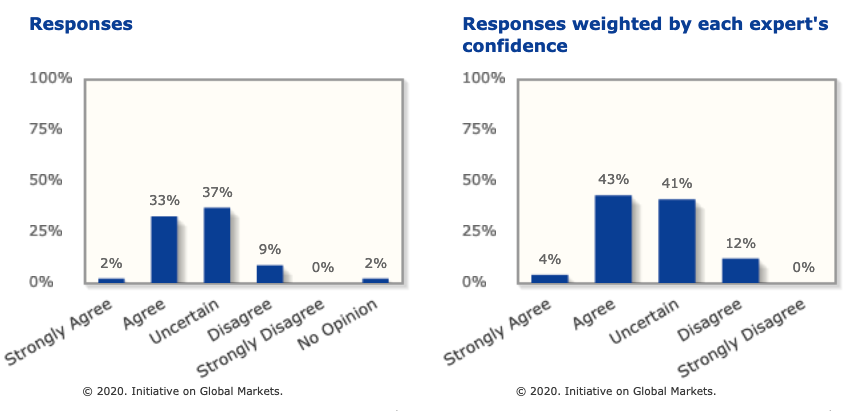

B. The economic effects of COVID-19 coming from reduced spending will be larger than those coming from disruptions to supply chains and illness-related workforce reductions.

Source: IGM Economic Experts Panel

In addition, we asked our European panel about the readiness of Eurozone policy institutions to respond effectively:

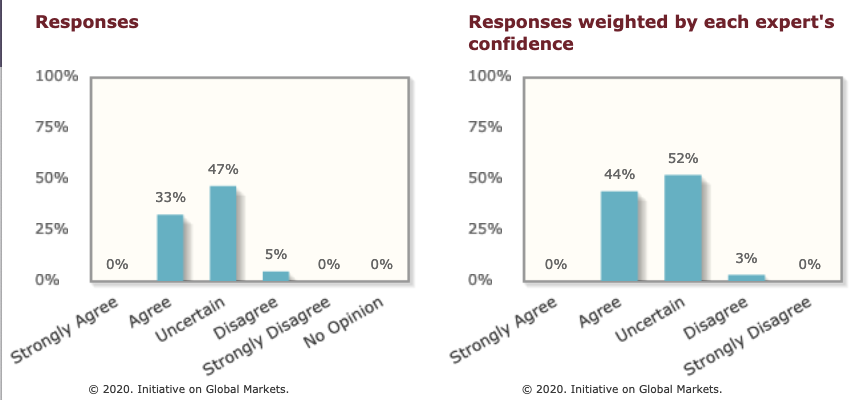

C. The economic policy institutions of the Eurozone are well equipped to ameliorate the potential economic damage from COVID-19.

Source: European IGM Economic Experts Panel

Of our 43 US experts, 36 participated in this survey; of our 46 European experts, 38 participated – for a total of 74 expert reactions.

Likelihood of a major recession

On the first statement on whether there will be a major recession, weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 19% of the US panel strongly agreed, 44% agreed, 31% were uncertain, and 8% disagreed.

Among the European panel (again weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response), there was a bigger majority agreeing that a major recession is likely: 48% strongly agreed, 34% agreed, 13% were uncertain, and 4% disagreed.

Question A. Responses from the European panel

Source: European IGM Economic Experts Panel

More details on the experts’ views come through in the short comments that they are able to include when they participate in the survey. These indicate a broad consensus across both panels that there will be a sharp downturn in the economy, but less agreement on how prolonged the dip is likely to be.

For example, Anil Kashyap at Chicago refers to the NBER’s definition of a recession. He comments: ‘a sharp slowdown is likely, whether it will be persistent enough to rise to the level of a recession is not clear yet’. And Jean-Pierre Danthine of the Paris School of Economics, who, like Kashyap, said he was uncertain, notes: ‘Two quarters of negative growth, yes; major recession: very uncertain, depends notably on policy reactions.’

Of the small number of experts who disagreed that a major recession is likely, Kenneth Judd at Stanford says: If it is like ordinary flu, then economy should quickly recover. COVID-19 only threatens old and feeble economic expansions.’

Among the majority who agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that a major recession is a likely consequence of the pandemic whatever its ultimate death toll (62% of the US panel and 82% of the European panel), several note the economic impact of the measures being taken to contain the pandemic. For example, Elena Carletti of Bocconi says: ‘The contagion rate worries more than the mortality rate itself as it shuts down the whole economy to contain effects on the health system.’

Along similar lines, Patrick Honohan of Trinity College Dublin responds: ‘Even if death rate is low, it will be because containment has been effective and that will adversely affect aggregate supply and demand.’ Luigi Guiso of the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance adds: ‘To stop its spread it requires stopping economic activity altogether – a major supply shock.’ And Richard Schmalensee at MIT comments: ‘”Major” might be a bit too strong, but the precautionary measures being taken in many countries will have a significant disruptive effect.’

Other experts point to what might be called ‘fear factors’: Larry Samuelson at Yale says: ‘The COVID-19 wreaks more havoc through panic and disruption than death. To avoid recession, we could view COVID-19 as we do the flu.’ Nicholas Bloom at Stanford notes: ‘Huge supply, demand and uncertainty shock. Vix [an indicator of expectations of market volatility] is almost as 50.’ And Darrell Duffie at Stanford comments: ‘We see initial signs of a recession in debt and equity pricing, and in fiscal and monetary policy responses.’

Xavier Freixas of Universitat Pompeu Fabra remarks on the impact of globalisation: ‘Contemporary interconnectedness between industries and countries turns a gridlock in one industry into a complete recession’. Christian Leuz at Chicago also alludes to interconnectedness: ‘The severity of the downturn likely differs by country, but in many countries the knock-on effects are already quite severe’. And Alberto Alesina at Harvard says: ‘If what is happening in Italy happens broadly, it will be a major recession’.

Pete Klenow at Stanford raises the spectre of wider costs of recession in terms of people’s broader economic wellbeing: ‘Sadly, the loss in welfare will exceed the decline in economic activity, given mortality and morbidity’.

Supply and demand shocks

On the second statement about the demand-side effects of COVID-19 on the economy being more significant than the supply shock, 44% of the US panel agreed, 52% were uncertain, and 3% disagreed. The results were similar for the European panel. Like the US panel, weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 4% strongly agreed, 43% agreed, 41% were uncertain, and 12% disagreed.

Question B. Responses from the European panel

Source: European IGM Economic Experts Panel

The absence of agreement among the experts on the relative importance of supply and demand shocks is also reflected in the comments. Pol Antras at Harvard says: ‘Both will be at play. For some sectors (services) demand will be key; but supply disruptions will be serious in manufacturing.’ Karl Whelan at University College Dublin adds: ‘This is both a major supply and demand shock. It is hard to see any circumstances in which measured GDP does not decline significantly.’ And John Vickers at Oxford comments: ‘Hard to disentangle supply and demand effects. And beware financial consequences – credit crunch, loan defaults, effects on insurers, etc.’

Of those who agree that demand-side effects will dominate supply-side effects, David Autor at MIT notes: ‘Supply chains are mostly about goods production, but manufacturing is under 20% of GDP. Services are a larger share of GDP and may be more exposed.’ Austan Goolsbee at Chicago adds: ‘Especially in rich countries where services dominate the economy, social distancing and withdrawal will be the toughest part.’ And Robert Shimer at Chicago comments: ‘Supply chain disruptions look to be short-lived. Income loss for hourly workers and those in travel, entertainment, etc. will matter more.’

Barry Eichengreen at Berkeley warns: ‘As someone who’s estimated lots of models designed to distinguish supply and demand shocks, good luck identifying them.’ Christian Leuz replies: ‘Obviously hard to separate supply and demand, but the question is essentially asking whether there is a big multiplier from the shock: my answer is yes.’

European institutions

The third statement, put only to the European panel, on the readiness of the economic policy institutions of the Eurozone to respond to the potential damage from COVID-19, weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, only 14% agreed that they are well equipped, 17% were uncertain, 48% disagreed, and 21% strongly disagreed.

Among the over two-thirds majority who disagreed or strongly disagreed, several comment on the inability to coordinate a fiscal response. John Vickers notes: ‘Lack of fiscal coordination. And financial sector measures could have adverse fiscal consequences in some scenarios.’ Karl Whelan says: ‘The absence of a common fiscal instrument (e.g. eurobonds) makes it difficult to have a large coordinated fiscal response.’ And Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute concludes: ‘Not without a change in fiscal attitudes and rules – which may come, under pressure.’

Others assume that it will not be Eurozone institutions that come to the rescue. Charles Wyplosz of the Graduate Institute, Geneva, says: ‘Besides the European Central Bank, which will play second fiddle, the really important actions will be at the national level, coordinated hopefully.’ And Joachim Voth of the University of Zurich comments: ‘Just like in 2007-08, Europe is out for lunch when it matters. The one viable actor in times of crisis is the nation state.’

Agnes Benassy-Quere of the Paris School of Economics points to her call at VoxEU, along with a number of other leading European economists, for the European Union to take responsibility for a catastrophe relief plan.

Finally, among US panel responses to the first question, Christopher Udry at Northwestern alludes to the policy implications of the economic impact of the pandemic: ‘An unusual recession, driven by the interactions of epidemiology, politics, psychology and economics. Needs a more creative response.’

All comments made by the experts are in the full survey results here and here.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the University of Chicago Booth School of Business’ economic experts panel, March 2020.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Free To Use Sounds on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Romesh Vaitilingam is a writer and media consultant, and the editor of CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. He is also a member of the editorial board of VoxEu. Romesh is the author of numerous articles and several successful books, including The Financial Times Guide to Using the Financial Pages (FT-Prentice Hall), now in its sixth edition (2011). As a specialist in translating economic and financial concepts into everyday language, Romesh has advised a number of institutions, including the Royal Economic Society, the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE and the Centre for Economic Policy Research. In 2003, he was awarded an MBE for services to economic and social science.

Romesh Vaitilingam is a writer and media consultant, and the editor of CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. He is also a member of the editorial board of VoxEu. Romesh is the author of numerous articles and several successful books, including The Financial Times Guide to Using the Financial Pages (FT-Prentice Hall), now in its sixth edition (2011). As a specialist in translating economic and financial concepts into everyday language, Romesh has advised a number of institutions, including the Royal Economic Society, the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE and the Centre for Economic Policy Research. In 2003, he was awarded an MBE for services to economic and social science.

Excellent post packed with information. Thanks, Romesh.