The twin forces of COVID and Brexit are altering the skills that people require to succeed in work. Skill levels remain low in the UK, compared to other advanced nations. About 30% of adults have low skill levels in literacy and/or numeracy, putting the UK as 12th highest out of 29 OECD countries. Job-related education and training is the key pathway to upskilling and wage progression for adult workers, and one of the biggest components of intangible investments by firms. Josh De Lyon and Swati Dhingra explore ways to incentivise employers to invest in training.

The pandemic has caused a sharp fall in total employment and work, with stark variation across sectors and occupations. A hesitant recovery from real wage stagnation started two years after the referendum, only to be knocked back down by the COVID-19 pandemic. This knock takes place against the background of weak wage growth recovery following the financial crisis, with real wages remaining below the 2008 level until the start of 2020.

Many of the changes introduced in the labour market are likely to be temporary – as the social distancing restrictions are eased, demand for in-person services would return. But the pandemic is also expected to cause lasting changes in the labour market. Just like any other crisis, COVID-19 is likely to create longer term reductions in employment outcomes and business survival. Perhaps most notably, the pandemic has incentivised a rapid co-ordinated adoption of remote-working technologies, meaning that many tasks no longer need to be completed at a specific location, or even from within the same country. Some of this is likely to be longer lasting.

During the global fight against COVID, the UK has left the European Union – its largest trading partner – and will now determine its own global trade policy, including the potential for new trade agreements elsewhere. Barriers to trade, investment, and migration between the UK and the EU have increased to varying extents across sectors of the economy, which will create profound changes in the distribution of economic activity across different parts of the economy.

All the while, technological change continues to alter the nature of the workplace, replacing the tasks of humans in some cases and augmenting them in others.

Together, these forces are altering the skills that people require to succeed in work. Job-related education and training is the key pathway to upskilling and wage progression for adult workers, and one of the biggest components of intangible investments by firms. In the UK, 2 in 5 adults participate in job-related education and training in any year. Adults with lower levels of education receive levels of training at half that rate: just 1 in 5 receive training. This compounds limitations on social mobility and contributes to wage inequality. Skill levels remain low in the UK, compared to other advanced nations. About 30% of adults have low skill levels in literacy and/or numeracy, putting the UK as 12th highest out of 29 OECD countries. Research shows that the prevalence of employer provided training has fallen in recent years, and that Brexit has caused firms to cut back on training expenditures to adjust to other increased cost pressures. Lower income workers have consistently received low levels of training, and the recent falls in training have been mainly among the young and higher educated workers.

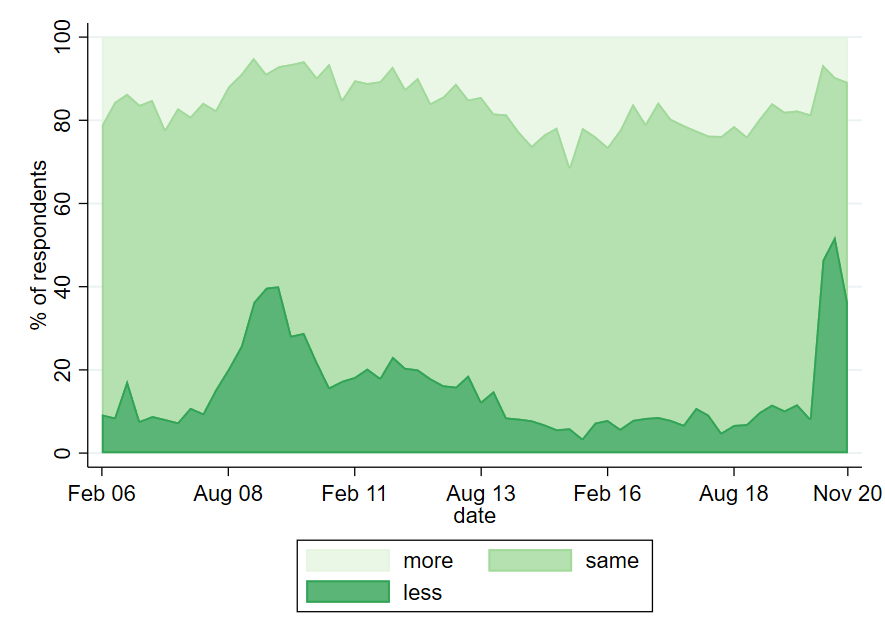

Figure 1 documents these trends in the services sector – which accounts for the majority of employment in the UK – using data from the Confederation of British Industry. The chart plots the percentage of businesses who reported a fall in their expenditure on training in the past three months. The decrease observed in the first period of data available after the first national lockdown is severe, with around half of firms reporting a decline in training expenditure. The initial change exceeds that of the Great Recession in 2007/2008.

Figure 1. Changes in businesses’ expenditure on training relative to past three months

The prevalence of training cutbacks alongside a major shake-up of economic activity is a worrying trend, particularly with the current turbulence in the labour market. Evidence suggests that adverse shocks to sectors or occupations are particularly hard felt by workers who are unable to transition to new work roles. Policies facilitating transitions to new skills are therefore fundamental for labour market resilience in both the short and long term. The government has already established the National Skills Fund since COVID-19 but more can be done, especially with government expenditure on job-related training down 18% in real terms since 2010.

The evidence presented here suggests that training provided by businesses has comprehensively fallen. In the UK, 82% of training expenditure is provided by employers. So, what can be done to incentivise employers to provide training?

First, tax credits for investing in human capital would be a start. Currently in the UK, businesses are able to claim generous tax credits when they invest in physical capital but there are no such across-the-board incentives to invest in training. Human capital is easier to scale up and has more positive spillovers than other sources of growth, adding to the argument that encouraging such investment would boost economic growth.

Second, the chosen policies should not aim to identify the reason why readjustment is needed, for example whether workers have been affected by international competition or by technological change, but instead focus on the specific support needed. Previous experience suggests that policies which aim to support workers affected by a particular type of shock, such as the US Trade Adjustment Assistance and the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund, have generally been less effective due to limited take-up as it is often difficult to identify the reasons for displacement.

Third, the apprenticeship scheme requires reform to more effectively target younger workers and broaden investment by the scheme. There are concerns that the current apprenticeship levy does not sufficiently incentivise firms to offer apprenticeships to younger workers, for whom the returns are higher, so the fund could be repurposed to specifically address this.

There is currently a clear need for extensive training programmes. Yet the recent trends of both employer-provided training and government policy on training leave a huge gap to be filled. With the March Budget fast approaching, policymakers must do more to provide and incentivise training and other support for workers. This is a necessary investment that will ultimately promote economic growth.

Authors’ Note: The research was supported by the UKRI’s Tackling Covid-19 funding.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared first on the site of the Institute for the Future of Work.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Alexandre Debiève on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy