Forcing employers to reveal their gender pay gap has been effective in its main goal of narrowing the gap. The difference between women’s and men’s pay has shrunk by just under a fifth at affected employers. Jack Blundell writes that female workers show a strong aversion to high pay-gap employers, suggesting that organisations have felt compelled to make changes in order to attract and retain workers.

The size of a worker’s paycheck depends on a vast number of factors, from family background to industry to the number of years they’ve been at their employer. However, a single factor, fixed at birth for most, explains a strikingly high share of wage variation across workers. Before Covid-19, the latest data showed UK women earned on average almost a fifth (17.3%) less than men. Though the gap has narrowed over the last few decades, at its current rate of decline it will take several decades more to close.

After years of delay and as part of a Europe-wide initiative on improving wage transparency, in 2017 the UK government introduced gender pay gap reporting. Since then, all private-sector firms and public-sector organisations with over 250 employees in England, Scotland and Wales have had to report a handful of statistics on the difference between male and female wages. Recent Covid-19 disruption aside, new statistics have to be reported every year.

The idea behind the policy is that making individual employers publicly accountable for their gender pay gaps will force them to explain why gaps exist, and in many cases to take pro-active steps to narrow them. This argument is not without academic grounding. There is a rich literature showing that transparency can have big effects on top wages. Part of the gender pay gap is driven by different approaches to salary negotiation, and increasing the information available to workers can help level the playing field. Practically speaking, transparency policies are a cheap way for governments to do something (or to be seen as doing something) about inequality.

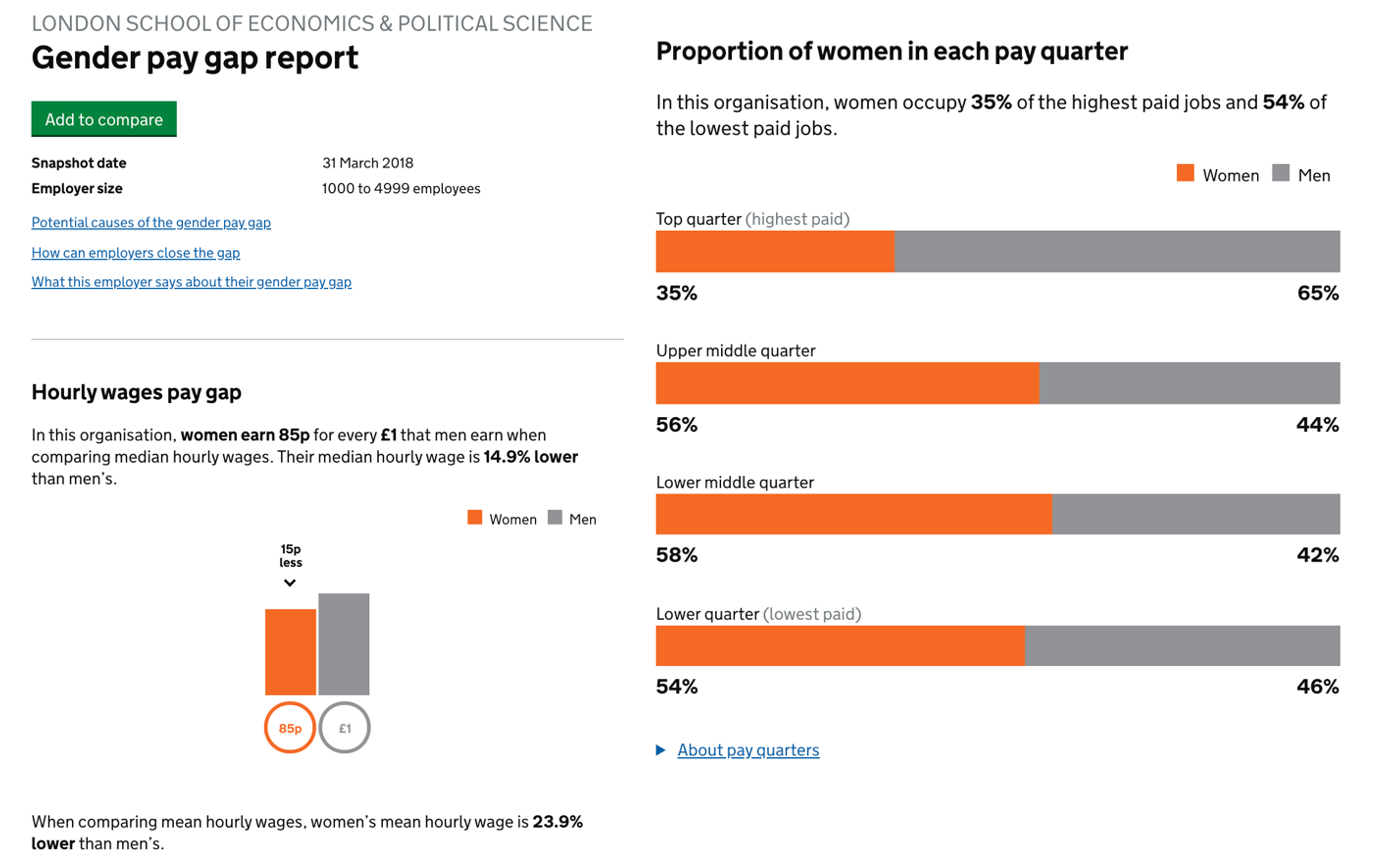

Figure 1. Gender pay gap report for LSE

Source: https://gender-pay-gap.service.gov.uk/

The policy has not been without its critics. Unlike in some other European countries employing reporting policies, the statistics reported are remarkably crude. They make no adjustment for whether or not workers are full-time or part-time, the type of job they are doing and their experience. We know that these factors can help explain some (but not all) of the gender pay gap. Furthermore, while employers are mandated to respond, there is to date little evidence of any serious enforcement in practice. Some pay gap reports are statistically unlikely and others downright impossible. Statistician Nigel Marriot estimates that up to 17% of first-round reports contained errors. One interpretation of this is that some companies lack the statistical capabilities required to construct the measures correctly. A less generous interpretation is that a minority of companies are deliberately fiddling their figures.

The chance to name and shame high profile companies has been seized by tabloids and broadsheets alike. In the first round of reports, The Independent ran with “Gender pay gap: worst offenders in each sector revealed as reporting deadline passes”, while the Daily Mail highlighted the high pay gap of low-cost airline Ryanair. Surveying 2,000 UK workers, I found that just under three quarters (71%) had seen news stories on gender pay gap reports.

Figure 2. Coverage in The Independent (5 April 2018)

Source: https://www.independent.co.uk/

How can we rigorously assess the policy’s impact on the gender pay gap? One simple approach would be to look at what has happened to the aggregate pay gap in the UK. This is unlikely to yield useful insights. Male and female workers are found in very different sectors, work in different occupations and hold different levels of seniority within employers. They also differ in their responses to aggregate economic shocks. This implies that male and female wages will exhibit different trends over short time periods, independent of the pay gap legislation. In other words, even if the overall pay gap declined around the policy introduction, it would be difficult to argue that this was due to the policy rather than some other factor.

Instead, I use the fact that only employers with over 250 employees had to report, comparing the pay gaps of employers either side of the 250-employee threshold. The argument is that employers with say 251 employees, who therefore have to declare their pay gaps, are likely to be pretty similar to those with 249 employees, who do not. These smaller employers can then arguably provide a control group against which we can compare the employers covered by the policy.

Applying this strategy to data on wages from 2012-2019, I find that the policy led to a 1.6 percentage point increase in women’s hourly wages relative to those of men. This is a large effect, corresponding to just under a fifth (19%) of the total gender gap in my sample. Interestingly, the effect is not driven by a reshuffling of highly paid women into affected employers, but rather due to changes in individual workers’ wages.

Before declaring the policy a resounding success, it’s worth noting that while women’s wages have risen, the observed closing of the gender pay gap is due to men’s wages rising by not quite so much. While female wages increased at the same rate at both affected and control group employers, male wages increased at a slower rate in affected employers than in control group employers. This implies that when compared to the control group, average wages at affected employers actually fell as a result of the policy, which typically isn’t great news for workers. Furthermore, this effect is rather immediate. It remains to be seen whether the impact will be sustained in the long-run.

So, why did employers act to close their gender pay gaps? In my survey, I find that while male workers are insensitive to pay gap information, female workers exhibit a strong preference against high pay gap employers. This is particularly true for young female workers, for whom ‘glass ceilings’ at companies are likely to be most relevant. The survey evidence is consistent with employers feeling compelled to make changes in order to continue to attract and retain workers.

My core results on wages are echoed in a concurrent study by a different research team, who furthermore highlight that employers are adapting their online job ads in response to the policy. Internationally, the picture is mixed. Analysis of a pay gap reporting policy in Denmark finds remarkably close results to those discussed here, but evidence from Austria finds their policy ineffective at closing the pay gap. Policy design details across countries differ in important ways, and in the future there is likely to be value in rigorous cross-country comparison studies.

The question of the policy’s effectiveness has become particularly relevant during Covid-19. In late March 2020, when the crisis started escalating rapidly, the government announced that it was suspending reporting for that year. Reporting is back on in 2021, but with a six-month extension to give firms a little more time. In light of mounting evidence of the crisis’ disproportionate labour market effects on women and a broader concern of gender equality taking a step backwards during the pandemic, there has never been a greater need for informed, evidence-based policies designed to ensure a fair and equitable society. My research suggests that transparency-based policies, even if somewhat crudely designed, can have a substantial impact.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Wage responses to gender pay gap reporting requirements, discussion paper 1750 of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Jordane Mathieu on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

The actual pay data in the UK shows a like for like (same function, level & company) gap of under 1%, i.e. it doesn’t exist.

This is based on data from the largest c&b consultancies who have access to v large samples of real pay data.