The increasing adoption of self-driving vehicles creates opportunities for innovation in other, related areas. Real-time data collected by car sensors might enable communication between vehicles, a prioritisation process for traffic movement — which would help reduce carbon emissions — and a dynamic toll system with the potential for new, innovative payment systems. Jamie Morgan envisions a “bid, offer, go” system in which vehicles take part in a competitive process using micropayments and digital wallets.

The UK, like many other countries, is taking another step towards self-driving vehicles. Achieving this, however, will not just be about the driving technology. Technologies often find their place in the world through the bundling of possibilities and through convergence of conducive circumstance. Most countries are encouraging transition to electric vehicles, and most envisage fossil-fuel transport taxes eventually disappearing. All of this suggests a need for new and innovative payments systems and a potential role for new forms of digital money. In a recent paper, I, like many others, have been wondering where all of this might be headed. What follows is just one possible area of application among many.

While GM’s Cruise was still a loss-making experiment last year and a lot of the current research is still focused on feasibility of driving technology, most countries are already someway down the road to autonomous driving systems. Beyond “no automation” (level zero), progress is typically broken down into five steps. First, driver assistance, such as cruise control. Second, semi-autonomous driving, where the vehicle is permissioned to initiate control over braking, acceleration and steering under specific circumstances (lane and distance control etc.). Third, autonomous driving, where driving can be delegated to the vehicle for some sustained period under predictable conditions, such as on a motorway. Fourth, fully autonomous driving systems able to cope with more challenging situations, such as negotiating environments that contain pedestrians and cyclists. Fifth and finally, fully automated systems. Here no human sits in a driver’s seat and maintains a degree of vigilance, so there is no one ready to take back control of the vehicle at a moment’s notice.

It is the third, fourth and fifth of these situations that create a use for new forms of digital money and its features, and developments in data collection lean into this. Traffic congestion becomes a new kind of problem in a world of automated driving systems. Car sensors and AI systems continually collect real time data on relative speeds and vehicle distances, and also match this to more global data on traffic flows and alternative routes to destinations. It is a small step from this to communication between vehicles to establish the most “efficient” combined speeds and route use. It is another small step from this possibility to the implementation of a dynamic toll system and to the formulation of some prioritisation process for traffic movement.

The simplest form of such a system would be “bid, offer, go”. Each vehicle has an inputted destination, preferred range of arrival times within a schedule and a budget. After that the vehicles could take care of the rest in a competitive process using micropayments and digital wallets. The user interface need not be complicated, though the process that sits behind it would be highly complex. If this seems farfetched, then maybe the rapid advancement of generative AI and the rush by competing corporations to roll it out, might change your mind.

Still, convenience and “wealthiest wins” are poor criteria for social welfare, and inequality distorts any claim to “efficiency”. Any rationally planned future with climate emergency in mind must also promote public transport solutions in a more unified transport planning approach. A readily foreseeable alternative to privately sponsored digital money might, therefore, be a central bank digital currency (CBDC) programmable money system. If only CBDC can be used for transport systems, then the state could constrain budgets, limit individual private vehicle usage through an energy/carbon expenditure metric, and introduce criteria for fairness, as well as traffic overrides to allow priority to be given to fully occupied private vehicles, public vehicles and emergency services. The broader implication here is that AI and programmable money create an opportunity for a new kind of administered and coordinated economy.

It has become increasingly clear that we are going to need greater intervention in order to address climate emergency. However, neither government nor the Bank of England is yet focused on the full potential here. The Bank currently envisages a retail CBDC “Britcoin” as a hybrid technology, where the Bank provides the core infrastructure and then eligible organisations provide a “payment interface” on their own platforms. The emphasis is on supporting commercial activity rather than thinking about how a climate resilient society might be administered. The UK government, meanwhile, treats technology as a piecemeal source of transitions, without properly thinking about more fundamental issues of social redesign that climate emergency invokes. Transport policy focuses primarily on the adoption of electric vehicles through the zero emission vehicle mandate. Behind this is a quiet assumption that substitution at similar scales of one form of vehicle for another is a sufficient adaptation and behind that is a broader assumption that it is mainly through the introduction of new technology within an equivalent society that climate goals will be met. This is also inherent in the Climate Change Committee’s main pathway:

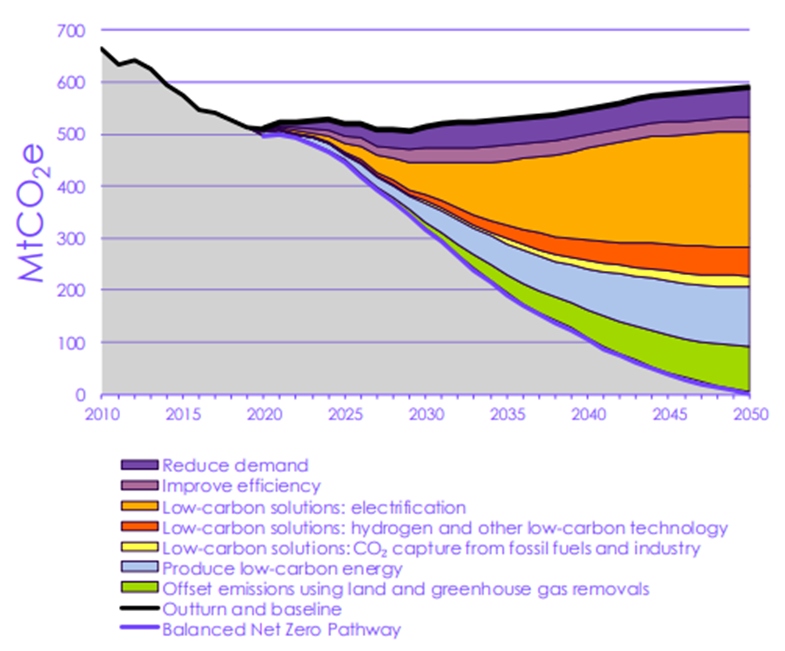

Figure 4. Types of abatement in the balanced net-zero pathway

Source: BEIS (2020) Provisional UK greenhouse gas emissions national statistics 2019; CCC analysis. Notes: ‘Other low-carbon technology’ includes use of bioenergy and waste treatment measures. ‘Producing low-carbon electricity’ requires the use of CCS in electricity generation.

Anyone familiar with the issues is aware that a significant part of this pathway is dependent on contentious assumptions about use of technology with limited changes to the kind of economy and society we live in (and this invites various debates around the feasibility of “net zero” versus “absolute zero”). Our climate predicament, however, requires more innovative thinking. Part of that, of course, is doing more locally, promoting walking and cycling and creating more transport options. But we must also recognise that we have built a society around roads and that we continue to build suburban housing estates that presuppose use of road vehicles. Still, how we think of the right to drive and ownership of vehicles need not remain the same. AI coordination, community vehicle ownership and programmable money are a possibility for administered mobility.

By now you have probably thought of numerous objections to what I have written (not least the energy consumption of digital money), and no doubt are thinking that there is something sinister and dystopian about the potentials of programmable money (since we are used to thinking of money as universal and anonymous source of getting your own way). Purposing money in order to dictate how (and in what period) it can be used may facilitate diversification and coherence of transport systems, but it is also, at least tacitly, transport rationing, and thus its use may seem like an attack on freedom. But social contract theorists argue that we give up some freedoms in order to enjoy others, and perhaps we now need a climate contract along similar lines. At some point, though, we are going to have to stop acting like we have choices we don’t really have. If we do, then perhaps we can democratise a future CBDC and purpose it by consent.

Does the future of transport depend on finding a place for new forms of digital money and their variants? No. But that isn’t how the social world works. Technology is not devoid of ontology. During the collapse of the dot.com boom, few were anticipating a world of platform technologies and social media. New technologies arrive, collide and hybridise and rarely is their eventual use obvious from their origins. At the same time, it is imagination that produces the very idea of possibility. This is the Star Trek Effect. It is most visible in the genesis of the smartphone, a technology once nascent and now a necessity. Creativity, however, is always with us. It perpetually holds out the prospect that we transform science fiction into fact. Futures are made and unmade and only in retrospect is the manifest “obvious”. This is the contradiction in the Star Trek Effect, an effect seamlessly stitched into the fabric of life.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Systemic stablecoin and the brave new world of digital money, Cambridge Journal of Economics.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Denys Nevozhai on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.