In their search for factors influencing UK monetary policy, Costas Milas and Michael Ellington trace the impact of geopolitical risks and oil prices on CPI inflation, GDP growth and monetary policy over the last 65 years. They write that these risks affect monetary policy indirectly through higher inflation and lower output. They also find that the response of UK interest rates to public dissatisfaction with the way the Bank of England is doing its job is statistically insignificant.

Rising geopolitical tensions over the past few years, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Hamas-Israel war in Gaza, and the attacks by Houthi rebels on Red Sea ships, provide challenges for policymakers both globally and in the UK. Recently, Chris Giles suggests that rising geopolitical risk will not add significantly to (global) inflation. Consequently, it is ‘OK’ for central banks to be complacent about Red Sea economic risks.

But is there a straightforward manner in quantifying the impact of geopolitical risk on the economy and, if so, has the impact of geopolitical risk changed over time? Recent academic research relies on Caldara and Iacoviello’s global geopolitical risk index to find that increases in geopolitical risk add to financial uncertainty and depress US private fixed investment, which bottoms out at about 1.5 per cent after four quarters. The US labour market also deteriorates, with hours of work declining by 0.6 per cent four quarters after the rise in global geopolitical risk. The same research uses cross-country regressions to find that higher geopolitical risk depresses next year’s annual GDP growth; the impact is four times higher when GDP growth is already weak. For the UK, recent research finds that rising geopolitical risk depresses Foreign Direct Investment inflows to the country and more so since 2000.

We assess the impact of geopolitical risk on the UK economy within an econometric vector autoregressive (VAR) model. This model looks at the relationships among five variables: the index of global geopolitical risk (GPR) threats of Caldara and Iacoviello, oil prices (transformed into £), four-quarter CPI inflation, output (that is, four-quarter GDP growth) and the policy interest rate set by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England (the last three variables are available from the Bank’s millennium database). We also allow for the effects of the pandemic lockdowns, which we proxy by UK’s stringency measures produced by the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford.

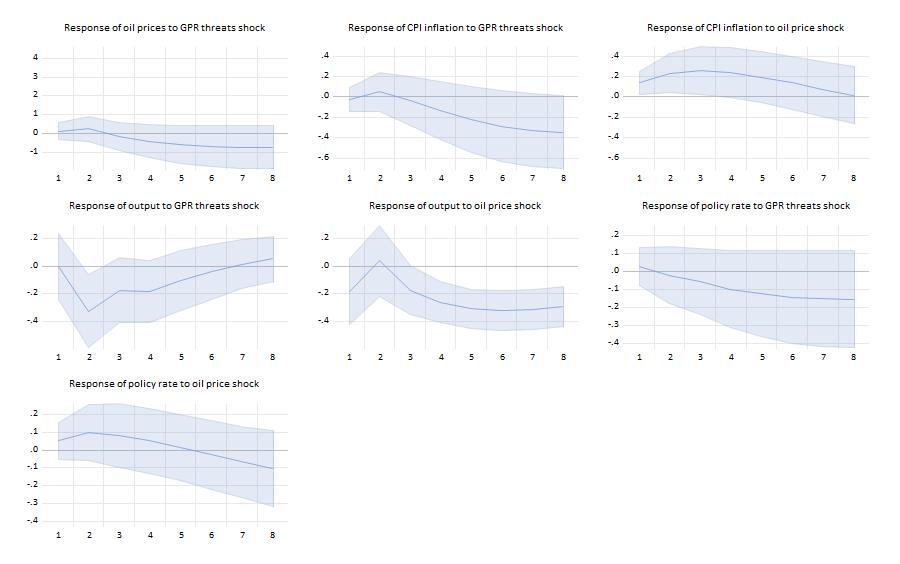

Our model allows us to trace the impact of geopolitical risk and oil prices on CPI inflation, GDP growth and monetary policy in the UK over the last 65 years or so. Chart 1 reports the impact (together with 95 per cent confidence intervals) over a period of eight quarters.

Figure 1. Sample: 1960Q1-2023Q4 (quarterly data)

We note the following:

- Oil prices and inflation increase temporarily after a rise in geopolitical threats. Nevertheless, these effects are statistically insignificant.

- Inflation rises following an oil price shock. The impact is statistically significant for up to four quarters.

- Output (four-quarter GDP growth, that is) drops (in a statistical sense) in response to rising geopolitical threats some two to three quarters later. The negative impact of oil price shocks on output is more persistent and kicks in from quarter 3 onwards.

- Monetary policy does not respond directly to oil price shocks or geopolitical threats.

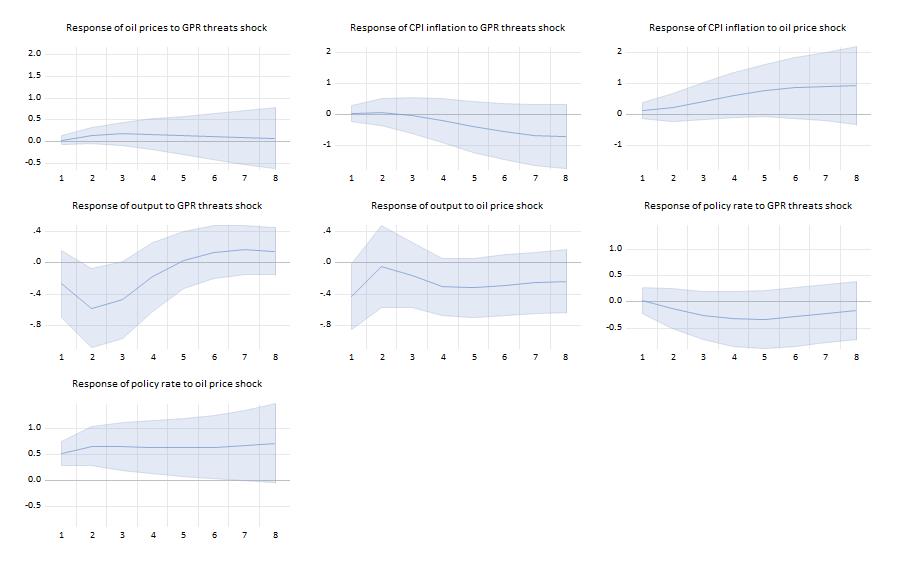

But has the impact of geopolitical risk on the economy changed over time? We re-estimate the VAR model only up to 1979. This takes into account the two oil price shocks of the 1970s but no further developments in oil prices or geopolitical risk since then.

Figure 2. Sample: 1960Q1-1979Q4 (quarterly data)

We note the following:

- The quantitative impact of oil price shocks on output is stronger than before (output drops by around 0.4 per cent two quarters following the shock as opposed to a drop of around 0.2 per cent, previously). However, the statistical evidence in favour of this is much weaker.

- The impact of geopolitical threats on output is also stronger than before; output drops by around 0.6 per cent as opposed to a drop of around 0.3 per cent when the whole sample is employed. This suggests that geopolitical risk has been more of an issue in earlier years than nowdays.

- As before, monetary policy does not respond directly to geopolitical risks. However, monetary policy tightens for up to eight quarters following an oil price shock when the sample of the first 20 years of data is employed (from 1960 to 1979, that is). This suggests that monetary policy has shifted from directly monitoring oil shocks in the past to much less nowdays.

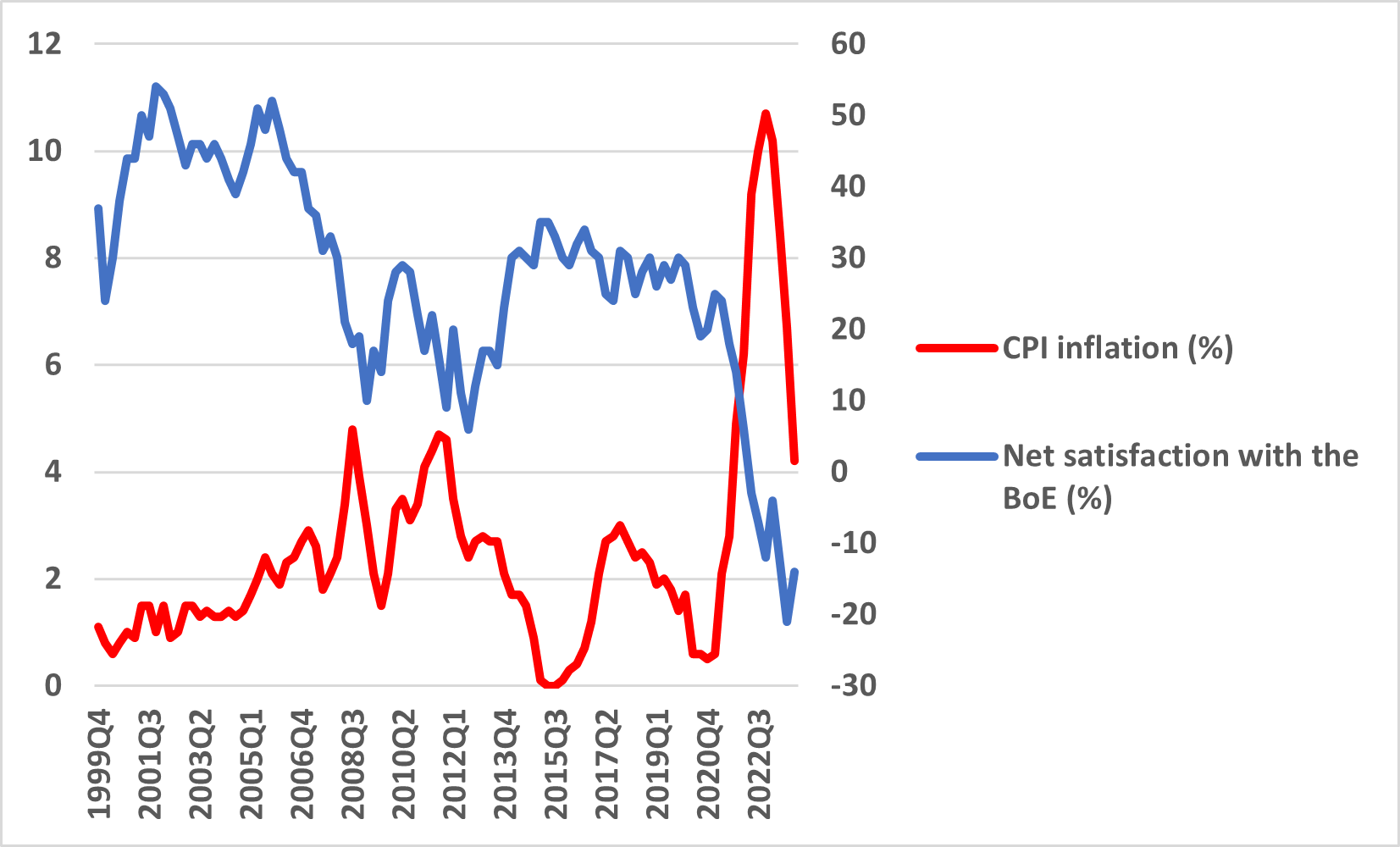

So if geopolitical risk does not affect directly, or to a significant extent, the MPC’s interest rate decisions what does? The BoE sets monetary policy to achieve the Government’s target of keeping inflation at 2 per cent. In addition, the BoE supports the Government’s other economic aims for growth and employment. However, the rapid rise in inflation since mid-2021 increases public dissatisfaction towards the Bank of England. Chart 3 plots together CPI inflation and the net satisfaction of the public (percentage of responders) with the way the BoE is doing its job to set interest rates in order to control inflation (a higher number indicates higher satisfaction). Notice that lower satisfaction associates with higher inflation.

Figure 3. Sample 1999Q4-2023Q4 (quarterly data)

Our model estimates can take into account public (dis)satisfaction towards the BoE. We drop geopolitical risk from our model (which does not seem to affect UK economic developments directly) and use, instead, net public satisfaction. Chart 4 reports the response of monetary policy to shocks in UK inflation, output (GDP) growth and net satisfaction of the public (together with 95 per cent confidence intervals). In line with its mandate, the BoE gives priority to inflation (higher inflation triggers higher interest rates) and less so to GDP growth (the response is largely insignificant).

Figure 4. Sample 1999Q4-2023Q4 (quarterly data)

Crucially, we show the Bank’s policymakers have not ‘lost their nerve’; the response of UK interest rates to net satisfaction with the way the BoE is doing its job is statistically insignificant.

The fact that our model suggests the public satisfaction does not sway the MPC’s decision on the level of interest rates is a positive. It adds credibility to the Bank of England in carrying out their mandate. With markets expecting interest rates to fall throughout 2024, public satisfaction with the Bank of England will undoubtedly rise as the transmission mechanism of monetary policy tightening depresses UK inflation further. As ever, the search for key variables influencing monetary policy continues.

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.