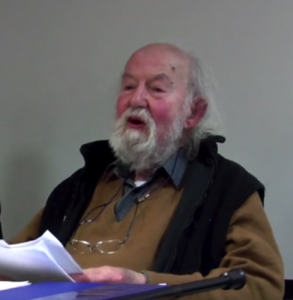

We are sad to announce the death of James Woodburn, a former colleague and one of the best-known researchers and writers on hunter-gatherer and egalitarian societies. He studied History as an undergraduate in Cambridge, then did national service, later taking an interpreter course in Russian. He returned to Cambridge, this time to do a BA in Archaeology and Anthropology. He conducted fieldwork in (then) Tanganyika, graduating in 1964 with a thesis entitled ‘Social organisation of the Hadza of North Tanganyika’. The Hadza remained his long-term field project; it was on the basis of this research that he developed his renowned insights into immediate- and delayed-return systems. He also collected Hadza material culture for the Horniman museum. While lecturing in our department, he supervised numerous doctoral students, including Roy Ellen, Jerome Lewis and Thomas Widlok, and played a particularly strong mentoring role to several African students, including Bwire Kaare and Wolde Gossa Tadesse. Two of his former students, Thomas Widlok and Wolde Tadesse, held a colloquium in his honour at the Max Planck Institute in Halle, later publishing the proceeds in a two-volume festschrift entitled Property and Equality (Berghahn). He remained a keen participant in the scholarly enterprise long after retirement, and was an honorary member of the International Society of Hunter-Gatherer Research. He regularly attended our Malinowski Lecture and went to CHAGS conferences, co-hosting one at LSE in 1986 and attending the last one in Malaysia in 2018.

We are sad to announce the death of James Woodburn, a former colleague and one of the best-known researchers and writers on hunter-gatherer and egalitarian societies. He studied History as an undergraduate in Cambridge, then did national service, later taking an interpreter course in Russian. He returned to Cambridge, this time to do a BA in Archaeology and Anthropology. He conducted fieldwork in (then) Tanganyika, graduating in 1964 with a thesis entitled ‘Social organisation of the Hadza of North Tanganyika’. The Hadza remained his long-term field project; it was on the basis of this research that he developed his renowned insights into immediate- and delayed-return systems. He also collected Hadza material culture for the Horniman museum. While lecturing in our department, he supervised numerous doctoral students, including Roy Ellen, Jerome Lewis and Thomas Widlok, and played a particularly strong mentoring role to several African students, including Bwire Kaare and Wolde Gossa Tadesse. Two of his former students, Thomas Widlok and Wolde Tadesse, held a colloquium in his honour at the Max Planck Institute in Halle, later publishing the proceeds in a two-volume festschrift entitled Property and Equality (Berghahn). He remained a keen participant in the scholarly enterprise long after retirement, and was an honorary member of the International Society of Hunter-Gatherer Research. He regularly attended our Malinowski Lecture and went to CHAGS conferences, co-hosting one at LSE in 1986 and attending the last one in Malaysia in 2018.

Watch video: James Woodburn: A Personal Account of my Life Among the Hadza 1957–1961 6 February 2018

Read article: Egalitarian Societies – James Woodburn

My condolence goes to the family and colleagues of Woodburn. We will surely missed him and will continue to admire his great academic achievements and numerous works.

I always remember James as a warm engaged person, interested in others and their research. But at the same time I found his advice for going to the field pretty daunting back in the 70s when I was a pre-fieldwork grad student in the department. Getting the local and Latin names of all plants encountered, by sending pressed specimens to Kew if necessary, was one that stands out. Obviously pretty essential if you are working with hunter gatherers, but less so for many of us shaking in our shoes and with other research plans!

Much later I remember with pleasure him saying he was simply going to fly his bicycle out to Tanzania, get on it at Arusha airport and cycle out to find the Hadza. I wonder if he ever did that. Many condolences to Lisa and his children – a unique somewhat larger than life person has most certainly gone from our midst.

James was a giant of anthropology. His writing, especially the famous lecture on egalitarian societies, combined theoretical rigour with deep respect and admiration for the people he worked with. As a student, it must have been ca. 2005, I attended an event James had organised in the Department of Anthropology at LSE. The purpose, as I recall it, was for Anthropology students to meet with two Hadza, who had come to London for the first time. A student asked about their impressions of the big city, one Hadza replied, and James translated: “so many people, but it’s very strange that you can’t see the stars.” Very strange indeed, and largely unnoticed by the city people. In my memory, James was the kind of anthropologist who didn’t explain away the experiences of others, but tried to convey them and translate them faithfully, so as to share the wonder.

I’ll miss our chats over dinner once a year. A pleasure knowing you!

When James talked about hunter-gatherer societies, especially the Hadza to whom he was devoted, his enthusiastic fascination with their way of life was always as striking as his scholarly expertise. But his interest in other cultures was never limited to them, for he was always glad to listen to his colleagues and students talking about the people they were studying, and he was an active, regular participant in the department’s Friday research seminars. In both the department and on school committees, James always spoke up for equity and fairness, especially towards students, and he consistently defended the academic principles that he saw as indispensable to a university in the face of threats from overbearing professors, managerialism, pointless bureaucracy, the audit culture, or external interference in general. Colleagues who wanted a meeting to finish on time were sometimes exasperated by James’s obdurate defence of principles that they regarded as petty conventions, but I don’t think anyone ever doubted his good faith and commitment to the collective interest. Thomas Widlok’s interview amply reveals James’s extraordinary determination and persistence in pursuing research among the Hadza, especially during his initial fieldwork, but these were qualities he displayed in many contexts. Sometimes, however, his determination to get it right became a kind of perfectionism preventing him from completing tasks, including publications, which he sometimes ruefully regretted in private conversation. Conversation was more often animated, though, by his amazing anecdotes, for example, about hunting animals for the Hadza with a gun (which he talked about in the interview) or carrying out major repairs on his Land Rover in the back of beyond in Africa (he was an excellent mechanic) or just about things he had seen and done during a long life. And what I think I’ll remember most about James is his friendliness as a colleague in the department for twenty years and afterwards during his retirement. I send my sincere condolences to Lisa and James’s family.

James Woodburn was in post at the Department when I joined it in 1996, 14 years after finishing my doctorate. James offered gestures from a kindred spirit to someone who felt at times the odd [wo]man out. As politics moved to disaster in the wider region of my research, in his quiet way James expressed sympathy for my political stances (Iraq, Palestine, Yemen) in exchanges that continued after his formal retirement. Condolences to those close to James.

When I arrived as a visitor to the LSE Anthropology Department in 1997, I was long familiar with James’ excellent ethnographic work on the Hazda and his important theoretical advances in the study of hunter gatherers. His attention to the significance of temporality and infrastructure in hunter-gatherer exchange and socio-economic organization provided valuable insights into egalitarianism. James was very kind and welcoming to me and I thoroughly enjoyed our many conversations, debates, and lunches together. He was a fine anthropologist and host. My sincere condolences to his family.

We personally, and the world, have lost “one of the greats”.

Arriving in Tanzania on one of his later visits and asked how he was doing, James responded “I’ve lost my brother and other friends recently. I’m acutely aware that the executioner’s axe is imminent – we must get on with it” (Classic James); whereupon we began planning and discussing objectives of our visit to the Hadza – where, who and what.

He was one of (if not the) the world’s experts on hunter gatherer societies from all reaches of the globe. But, his interests were much broader.

What a privilege to spend time in the field with someone so interesting and so interested in a diverse range of topics & issues from the details to the overarching.

Even his proclivity for perfection, which could be annoying, even exasperating, did lead to results that were accurate, articulate, eloquent and sound of reason.

Almost certainly, he knew the Hadza & their society better than any other non Hadza. More importantly, he cared deeply about them as individuals and as a group. When the Hadza were informed of his death, they collectively gathered honey and brought it on a two day journey to Arusha as a tribute to a man they considered one of them.

He is missed.

Condolences to Lisa, Cessi and family.

I too benefited from James’ warmth and collegiality when arriving at LSE as a ‘rookie’. As I got to know him better I was impressed by his caring attitude, especially towards his PhD students (among whom were several scholars hailing from or based in Africa). His works on Hadza ethics of egalitarianism will endure and inspire new generations of students. Condolences to his family and close colleagues.

In 2007, James joined us in Mykonos (Greece) to help Elena Mouriki (a doctoral student of Camilla Power) and her Hadzane field assistant Susana Zengu, in the laborious work of transcribing recordings of Hadza myths and translating them – either into Swahili (Susana) or straight into English. He was recovering from a recent heart operation. One day, I told him I was going to clamber down the cliff below the house for a swim. James wanted to come too. I tried to dissuade him, as it was slightly dangerous, but he insisted. He wanted to test himself, in preparation for an upcoming field trip with Jerome Lewis to Ethiopia – looking for former or remnant hunter-gatherer groups.

Bringing these stories recorded by Mouriki into the public domain would be a fitting tribute to James.

So sad to hear of James’ death. He was a wonderfully supportive tutor when I was a second year undergraduate and later became a good friend. A great anthropologist and yet so modest. Besides his work with the Hadza, and his active support for their land rights, I’d like to pay tribute to the central role he played in the development of ethnographic film as part of anthropological practice.

My condolences to his family.

I’m very sad to learn of James’s death and I send my condolences to Lisa and his family. I first met James in 1958 when I was a newly-arrived District Officer in Tanganyika. I was at my home in Mbulu one day when James drove up in an open Land Rover accompanied by two Hadza. He had come to introduce himself and to buy some supplies from our local shop. So we all sat down and had a cup of tea. After that James dropped in from time to time and sometimes stayed the night and enjoyed a good bath. I was transferred soon after to another district, and subsequent meetings with James were few and far over the years, but we kept in touch. I valued his warm friendship.

So sad to hear of James’s death. I remember him very fondly, driving through the savannah in his ancient jeep, full of Maasai and lentils. Advising us to shout at lions if we were cornered…

Most of all, I thank him because he really did change my life through the amazing support he offered. He was a one off in so many ways and remained to the end absolutely passionate about his subject. Passing of a great..

Condolences to Lisa, Becca, Naomi, Cessi, Emma and all the family.

I never had a chance to get to know James personally that well. But I have long cherished his writings on the Hadza and egalitarianism. I recently went back to his Malinowski lecture. I did this as a tribute to his memory and since I was not able to attend the memorial occasions held in London or in Cambridge on his behalf. I discovered, once again and to my great delight, what a powerful lecture this was!

Incredibly sad to know James Woodburn died. I good to know him well on my 2nd and 3rd year undergrad at the LSE. Every two weeks I presented papers to him and we became friends. I quickly decided I wanted to do my field work on hunter-gatherers and after two years in Paris I went back to the LSE and prepared to go for fieldwork in the Philippines. James was, of course, my PhD supervisor. And our friendship became solid: for one year and a few months, every school day, I would spend easily a couple of hours with him. God, what I learned!!! After almost 3 years in Northern Luzon with the Atta I returned. And there he was as a friend, solidly, and as a supervisor.

Complicated matters led me astray as one of my brothers died in a car crash and I simply quit and went to Angola as a diplomat. I did end up getting my PhD elsewhere.

I saw James a handful of times as I returned to Europe after 5 years, every time I went to London.

I miss him terribly.

To his Family I would like to send my kindest regards. It was only today that I knew of his departure and I feel broken.

T.