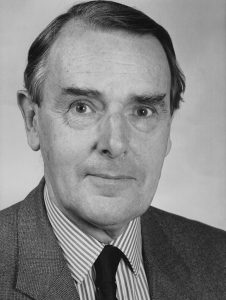

It is with deep regret that we announce that Emeritus Professor Ian Nish died on 31 July 2022 at the age of 96. Ian was a member of the Department of International History from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. He was one of the world’s leading scholars on the foreign relations of modern Japan and had an exemplary career as both a researcher and a teacher.

It is with deep regret that we announce that Emeritus Professor Ian Nish died on 31 July 2022 at the age of 96. Ian was a member of the Department of International History from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. He was one of the world’s leading scholars on the foreign relations of modern Japan and had an exemplary career as both a researcher and a teacher.

Ian was born in Edinburgh in 1926. Towards the end of the Second World War he started to learn Japanese as a young soldier in India. Having graduated from the School of Japanese in Simla in 1946, he was sent the following year to Japan to serve with the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Kure where he engaged in interrogation work. Ian was therefore the last member of the great generation of Japanologists who emerged from the war, which also included similarly eminent figures such as the late Ron Dore.

In 1948 Ian returned to the UK and began an undergraduate degree at Edinburgh University, before embarking on a PhD at SOAS under the supervision of W.G. Beasley. His first academic post, before he moved to the LSE, was at the University of Sydney. In 1966 he published his first book, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance: The Diplomacy of Two Island Empires 1894-1907, and this was followed in 1972 by Alliance in Decline: A Study in Anglo-Japanese Relations 1908-23. These two volumes remain fifty years later the standard histories of the alliance. In addition, Ian wrote several other major books that continue to influence the field, including The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War (1985) and Japan’s Struggle with Internationalism: Japan, China, and the League of Nations (1993).

Outside of his writing, Ian made a great contribution both to the School and to the field of Japanese studies. As well as his departmental duties at the LSE, Ian was closely associated with the founding and running of STICERD. He sat on its steering committee and contributed greatly to its International Studies programme, bringing a brilliant range of both young and established scholars of East Asia to speak at its seminars. He was also a chairman of the School’s publication committee, of the Centre of International Studies, and of the senior common room.

In the field of Japanese Studies, Ian was one of the key individuals in nurturing this discipline in the UK. He was an instrumental figure in the establishment in 1974 of the British Association of Japanese Studies and became involved in the running of the European Association of Japanese Studies, acting as its president from 1985 to 1988. In addition, He chaired the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee from 1983 to 1991 and served as a member of the DTI’s Advisory Committee on the teaching of Japanese language in the UK. Ian was also an enthusiastic member of the Japan Society, served on its Council, and played a major role in its scholastic activities.

In 1990, Ian received a CBE for his contribution to Japanese studies and then in the following year, on his retirement, the Japanese government awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun.

Ian clearly deserved a long and happy retirement after the above labours, which came on top of his being an inspired guide to the history of Japan to undergraduates, postgraduates and his PhD students. Indeed, soon after retirement Ian looked younger as the worst stresses of administration fell from his shoulders. Being Ian, though, this did not mean that he had decided to rest.

In 1995 Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama announced that, in order to understand the Second World War and Japan’s role within it, the government would finance a programme of historical studies of its most significant bilateral relations. This led to the formation of the Anglo-Japanese History Project in which Ian acted the convenor for the British contributors, while his long-standing friend, Professor Chihiro Hosoya, was chosen as his Japanese counterpart. The Project involved a series of conferences and workshops being held in Britain and Japan in the late 1990s. This work, in due course, led to the production of six volumes of essays, published in both English and Japanese, covering the political/diplomatic, economic, cultural, and strategic interactions between the two countries. It was an immense undertaking but proved invaluable for the field. Following this strenuous endeavour, Ian continued avidly with his own research. In 2016, at the age of 90, he produced his last publication, a two-volume History of Manchuria, 1840-1948. Even after that, he did what he could to keep up with the field.

Ian will be remembered as a giant in his field, but, in addition, as many of the messages of condolence to his family and friends reveal, he will also be thought of warmly for his great kindness. Ian was a true gentleman, always polite, and never speaking ill of anyone, but also armed with a dry and sometimes mischievous sense of humour. He and his late wife Rona delighted in inviting guests to their house in Oxshott, and those of Scottish blood would come down in January to share a haggis on Burns Night. He will be greatly missed by very many people across the world.

We send our deep condolences to his two daughters, Fiona and Alison.

_________________________

With thanks to Professor Antony Best, from the Department of International History, for sharing this tribute.

The date of Professor Ian Nish’s passing has been updated to 31 July 2022, with apologies for the initial oversight.

I was so very sad to see that Ian has passed away. During my many years working at the LSE he was always a great support and source of wisdom both academically and in navigating the ways of the School. His work on Japan’s foreign relations remains that standard that many of us would like to beat, but will never be able to do so. My sincere condolences to his family and loved ones. A huge loss to academia and the School but a wonderful life of achievement that we have all benefitted from in Asian studies and international relations.

I was sorry to hear so belatedly that Ian had died. He was a leading light for me, though a Russianist. He backed me for the top scholarship at LSE and he stood by me after I applied for a job there and met with a veto from a leading anti-communist and economist on the appointments committee. He made sure I knew why I had failed, some years thereafter through a colleague. And he was there to the very end when I sought advice on the latest historiography on Japan only two years ago.